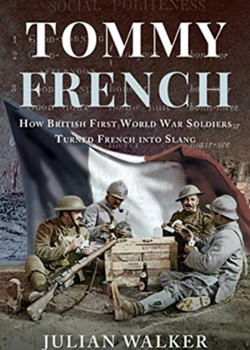

Tommy French: How British First World War Soldiers Turned French Into Slang

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Tommy French: How British First World War Soldiers Turned French Into Slang

£19.99, Pen & Sword, 2021, 224 pp

30 b/w illustrations

ISBN: 9781526765925

[This review by Rachel Duffett first appeared in the October 2021 edition of Stand To! No.124]

Parley voo frongsay? 'Napoo', 'compray', 'san fairy ann', 'toot sweet' - all are anglicized French phrases that came into use on the Western Front during the First World War as British troops struggled to communicate in French.

Most of the First World War British Army certainly couldn’t, language skills not being the top priority of a state education system that had, pre–war, been much more concerned with improving science teaching and PT in response to perceived threats from Germany. While many of the officers on the Western Front had the chance to practise their schoolboy French, the rankers were reliant on the multitude of English/French phrase books and dictionaries produced in a mini publishing boom. They were packed with helpful phrases such as ‘I will give you a button’ or, very optimistically in January 1915, ‘We shall be in Brussels in three weeks’.

Julian Walker’s wonderful study makes much of the humorous juxtaposition of the unsophisticated Tommy with the mysteries – both linguistic and cultural – of the Continent. The book is, however, about much more than that and covers a far broader range of experiences than the title might suggest. Walker has fascinating things to say about everything from the employment of military interpreters and interactions with French civilians to the academic studies of English soldier slang in the universities of interwar Germany.

A great deal is made of the cultural position of France in British consciousness and how, for much of the youthful British Army, it was regarded as ‘the land of mythical sexual promise’. Walker is excellent at highlighting the exotic nature of all things French in common parlance, whether letters or lessons the prefix indicated a world of carnality of which the average Brit could but dream. He is also strong on the commercial relationship between soldiers and French citizens, the way in which this ‘drove the seller to use the buyer’s language’. The breadth of primary material employed is impressive and the author ranges from the postcards, letters and phrase books of the front to the manner in which French was employed in product advertising at home. It is also good to hear the voices of some of the women on, or behind, the Western Front and Walker uses material from nurses in particular to great effect.

This is a book that, in places, leaves the reader wanting more, for example, on the emotional aspects of language and war, how code–switching, the use of phrases like ‘c’est la guerre’, allowed men to glide over the brutal realities of battle in their correspondence with home. The structure is a little fragmented and while all the chapters are individually absorbing, it would have strengthened the book if the overarching themes had been more visible. In particular, a conclusion that draws the multitude of threads together would remind the reader of the reach of the book in a way that a brief ‘Afterword’ on the origins of ‘plonk’ doesn’t. But these are minor criticisms of a terrific study that deserves a place on the bookshelves of anyone who has an interest in the experience of the British soldiers of the Western Front.

Rachel Duffett