War Books by David Filsell 2005

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- War Books by David Filsell 2005

War Books: A reflection on some contemporary views by David J. Filsell, for Stand To! No.74 September 2005

'Frightened of War Books'

Although many books published in Britain during the Great War were propagandist, interest in 'war stories' remained at an extremely high level between 1914 and 1918. Only when the conflict ended did interest decline. Works of literary merit were published between 1919 and 1928, but it is now generally accepted that during the 1920s, in J. B. Priestley's words, 'publishers had become frightened of war books - except, of course the records of very important people'.(1)

The writer H. M.Tomlinson expressed a similar view in 1930. Noting that during the war 'the emotions of the public were kept at high tension with shocks of propaganda'. He added that for some years after the war 'publishers and readers were very shy of war-books'.(2) ’He reported:

Now, we learn, there is a distinct and growing disposition to revisit the glimpses. It is said that the public is now showing the desire to read, sometimes with great approval, stories of war .... (3)

In reality the renewal of interest had flowered in 1928 with the publication of three books which elevated writing about the conflict to an important level. A number of academics and historians have put forward the view that it took some ten years for those authors who served between 1914 and 1918 to mature, to hone their writing skills to a level which enabled them to gain some form of what is now popularly termed, 'closure' through writing about their experiences.’ (4)

Amongst the important works published in 1928 were Edmund Blunden's ‘Undertones of War’, and Siegfried Sassoon's ‘Memoirs of Fox Hunting Man’. It was also the year of the first performance of R. C. Sheriff's Play ‘Journey's End’, a play which was to be translated into 27 languages, including Siamese, and rewritten as a novel.

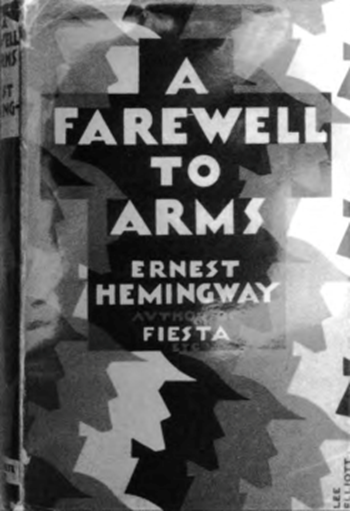

In 1929, when Journey's End started its long West End run to outstanding reviews, further works generally judged important were published. Richard Aldington's Death of a Hero, Robert Graves' ‘Goodbye to All That’ and Ernest Hemingway's ‘A Farewell to Arms’ all attracted considerable praise. So too did two translations from the German: Ernst Jünger's ‘The Storm of Steel’ and Erich Maria Remarque's ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’.

The day of publishers' fear and readers' disinterest had been breached, and the success of these works at least aided the successful publication of more important works in 1930. Not least among them were books by Frederic Manning (Her Privates We), Siegfried Sassoon (Memoirs of an Infantry Officer) and Henry Williamson (The Patriot's Progress).

Although the day of important writers' personal recollections or novels based upon their experiences is long over, discussion of their work continues almost unabated. Instead of works generally recognised as literature we are now flooded with very different books. Serious - and welcome - analysis of battles, of technology, of individual rankers and great captains alike, and even uniforms, predominate as authors and historians re-evaluate widely varying aspects of the war. Yet lists of 'favourites' or 'the best books of the war' regularly highlight literary works of the 30s, which have been regularly republished, often with new introductions to put them in context.

Although modern analysis of the 'important' works about the war published in the 1930s ignores some which contemporary critics thought important or undeserving of praise, a constant is the number which has stood the literary test of time. Quite apart from Cyril Falls' well known and highly regarded annotated bibliography of works about the Great War, ‘War Books’, published in 1930 (5) - many other writers and critics expressed their views about war literature. The opinions of five 1930s critics - all themselves able writers - can be called in witness: J.Knight Bostock, an academic; J. B. Priestley, a former soldier, popular writer and critic; H. W. Tomlinson, a war correspondent, literary editor and novelist; Graham Seton (Lt Col G. S. Hutchinson), a decorated soldier, wounded four times, author and press publicist; and Douglas Jerrold, who served in Gallipoli and France with the Royal Naval Division, an author and publisher.

Graham Seton Hutchinson

Writing under the name Graham Seton, Hutchinson compiled one of the fullest and most enigmatic articles of criticism and comment in the 1930s. It was first published in John o'London's Weekly, and later reproduced in his somewhat vainglorious autobiography ‘Footslogger’ in 1931. A controversialist, who developed strong fascist beliefs, Seton justified his opinions with the blunt and accurate statement that he had 'some authority as a soldier'.(6)

He split works into three categories: pure fiction; history and sheer reporting, and the 'innumerable' works of fiction which purport to offer a psychological examination of a soldier's mind in Flanders'. In a wide-ranging summary he recommended seven books - all 'different in atmosphere, in viewpoint' - which he considered 'incomparably better than the rest'. They were Blunden's ‘Undertones of War’; Graves' Goodbye to ‘All That’; Frederic Manning's ‘Her Privates We’; Jünger's ‘The Storm of Steel’; Arthur Conan Doyle's now little-regarded British ‘Campaigns In Europe 1914-1918’; Phillip Gibb's ‘Realities of War’ and R.H. Mottram's ‘Sixty-four Ninety-four’ (the final element of the author's work The Spanish Farm Trilogy). As a coda he included AD Gillespie's ‘Letters from Flanders’ and '’Colonel Fielding's ‘Letters to his Wife'. (7)

In amplification, Seton thought ‘Undertones of War’ was 'supreme'. It was, he wrote, 'an epic which I predict will outlive every other book concerning the period 1914-1918'. ‘Goodbye to All That’ was described as 'truthful and vivid' and, even if not in his top seven, C. R. Benstead's ‘Retreat: A Story of 1918’ was also accorded considerable praise.

Of works in German he wrote that ‘The Storm of Steel’ was 'sheer reporting and it has gripped me as no other German war story has done'. ’A Subaltern's War’ by Charles Edmonds was also esteemed. It was, Seton felt, written by 'a lad with clear eyes, who 'saw what a Brass Hat could not'. Yet his taste was broad ranging, since he judged the Red Knight of Germany’ (8) to be a 'vivid story of a unique character' which should be 'on everybody's library list' and W. F. Morris's forgotten 'Hannayesque' adventure ‘Bretherton: Khaki or Field Grey?’ was, he added, simply 'thrilling'.

Amongst the books he termed 'psychological fiction', Seton included a number by German authors. The expressionist, widely influential, and now largely neglected collection of short stories, ‘Men in Battle’ (9) by the Austrian writer Andreas Latzko, although 'filled with crass sentiment', he thought the work of a writer with a gift of description. Yet neither Arnold Zweig's highly lauded novel about a cruel episode in the war on the Eastern Front, ‘The Case of Sergeant Grischa’.

Although now almost forgotten, ‘Zero Hour’ was widely praised in Germany on publication in 1928, not least by Thomas Mann. Neither the striking cover of this US edition or its content seems to have interested English readers greatly and the book is now a rarity. Although Graham Seton considered that it possessed ‘much merit from a psychological viewpoint he considered that its author 'perpetually irritates' in his writing.

A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway's second novel, was widely praised by J.B. Priestley, amongst many others, on publication in 1929. Although the book 'worthy of the part', Graham Seton considered that, overall, the wartime service of the US army ‘had not been well served by its writers'. Now extremely rare in Lee Elliott's striking cover to the first English edition, the book is more highly regarded by collectors of modern fiction first editions than by those interested in Great War writing.

Grischa, although 'finely told', nor Georg Grabenhorst's ‘Zero Hour’ - whose writing he recorded 'perpetually irritates' with its expression of 'What a fine fellow am I' - found great favour.

Seton also offered praise for C. E. Montague's ‘Fiery Particles’, Richard Aldington's Death of Hero’ (10) and A. M. Burrage's ‘War is War’ (published under the pseudonym 'Ex-Private').

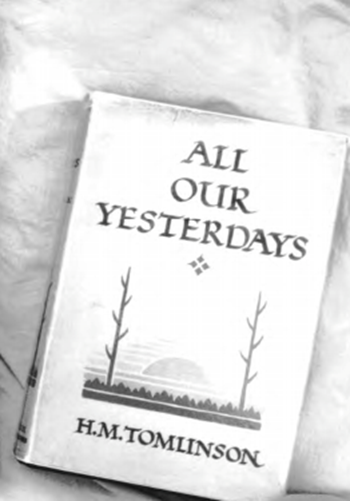

Of American writers he noted only Ernest Hemingway's ‘A Farewell to Arms’ as 'worthy of the part'. The works of two French writers, Henri Barbusse's ‘Le Feu’ (11) and Ronald Dogeles's ‘Les croix de bois’ (12) were both judged 'superb'. Of now largely-forgotten books, he offered commendations to Gilbert Frankau for his novel ‘Peter Jackson Cigar Merchant’ and E. M.Tomlinson's for ‘All Our Yesterdays’.

Works dismissed, or scorned, included Mary Lee's ‘It's a great war’ (sic), W. T. Scanlon's ‘God have Mercy On Us’, C. Y. Harrison's ‘Generals Die in Bed’, F. P. Crozier's ‘A Brass Hat in No-Mans’ Land‘ and Helen Zenna Smith's (pseud.) ‘Not so Quiet’.

But Seton reserved particular ire for Erich Maria Remarque's ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’. It was, he wrote, 'vile and degrading', a view he claimed to share with every German soldier with whom he had discussed the book. Any modern judgement may be in broad agreement, at least, with Seton's selection, and his was not a lone voice in expressing dislike for Remarque's best-known work. Although a worldwide best-seller, and still the best known and most widely read German book about the war, it was not universally praised. The popular J. B. Priestley, whose initial view of the book was positive, certainly later revised and downgraded his opinion of its merits.

In Germany, views of the book were equally mixed. Many ex-soldiers, particularly those on the political right, detested its bleak picture of war and regarded the work as dishonest and self-serving. Some went further, and in the notorious, and carefully orchestrated, book burnings in Berlin's Opernplatz, in May 1933, student representatives of the Nazi Party proclaimed it 'a literary betrayal of the (German) soldiers in the World War'.

Knight Bostock

In a slender 1931 analysis, Some well known German War Novels 1914-1918, J Knight Bostock provided his own detailed and relatively dismissive analysis of Remarque's novel, and its author, and offered an overview of the negative reactions to the work in Germany. Bostock himself felt:

In style too Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front) is negative. The sentences are short and disjointed. The situations are not worked out in detail, and the characters are mere types.(13)

Bostock had a refined ability to condemn whilst offering apparent praise. The reasons for the success of ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, he wrote, apparently dismissively, were its 'skilfully chosen words' and its 'dropped hints that set the readers' imagination working'. Reflecting on Remarque's previous career in the press, he added that 'It is clever journalism but is not great literature'. Mirroring Priestly's revised opinion of the work, Bostock added, 'if the book is re-read deliberately after the first flush of excitement has passed, it appears very dull'

Bostock's pamphlet was not, by the author's own definition, complete in its study. The books he selected in their original German editions were, he wrote, 'typical, adding that they were 'the most important examples of a not very high class of literature that cannot be ignored by the historian'. In truth, although his evaluation of German books remains valuable, it is essentially dry and academic. Praise for any of the works he evaluated is constrained. Although his view was drawn from German editions, a number had been, or were later, translated into English and few gained Bostock's commendation.

‘Krieg’, by Ludwig Renn, translated as War, and widely praised in the United Kingdom, was dismissed as containing 'unnecessary detail'; written as if the author was 'talking to his cronies in the inn'. Bostock also noted dismissively that it 'has been rather extravagantly praised as the only book that tells the whole truth about the war'. Nevertheless he correctly noted that it 'has been more successful than any book about the war except ‘Im Westen nichts Neues'.

Bostock felt that ‘The Storm of Steel’ showed Jünger's 'outlook too narrow to be impressive, for war appears to have become his monomania'. He added that the author was a man 'who would be warmly welcomed by an aristocratic tribe of headhunters desirous to remodel their methods on modern West European lines'. A similar opinion of the strident Jünger has been more recently expressed by the highly rated German bom author and academic W. G. Sebald who dismissed Jünger as a writer:

who had emerged from the Hitler era, which he had helped to usher in, as a distinguished isolationist and defender of human values. (14)

Amongst the works readily available in English translation only Zweig's novel offered Bostock objectivity, a view of war from a distance, that accorded to his taste.

Henry Major Tomlinson

A far less elitist view of War Books had been expressed in a lecture at Manchester University by H. M. Tomlinson in February 1929 in which he stated that the recognition of true virtue was not easy, adding, 'yet is not the case for all literature the same?' (15) Tomlinson spoke with an easy authority. A writer of rare ability, he had been The Daily News war correspondent in Flanders and later Literary Editor for The Nation. As well as praise from Seton, his 1930 war novel

Shattered trees have long offered a short depiction of the effects of war in both art and literature. The handsome large format 1989 edition of Edmond Blunden's ‘Undertones of War’ (above) also offers a range of selected images by leading British war artists together with Blunden's war poetry.

A similar stylised image was selected for the jacket author and critic H. M. Tomlinson's now neglected ‘All Our Yesterdays’, 1930. Critical of 'fireworks' in writing about the war, Tomlinson's great work about the war was nevertheless 'commended' by the capricious Graham Seton.

‘All Our Yesterdays’ was to gain plaudits from both J. B. Priestley and from Hugh Walpole who wrote of: 'It's lovely English', 'Its nobility' and 'Its reality'.

The criteria which Tomlinson employed in his selection of important works seem particularly sound. In pure and elegant prose he stated that although the subject of a great book was unimportant, he considered it essential that such a work should offer 'unexpected light'. He felt it equally important that it should be neither heroic nor rhetorical, offer neither mere argument nor 'fireworks' and provide elements of melancholy.

Winston Churchill's 'History of the War' - almost certainly an imprecise appellation for Churchill's five-volume work The World Crisis - which had been hailed by 'important critics' failed Tomlinson's tests. In analysing sections of Churchill's writing he concluded that it lacked wisdom and displayed a 'Lack of control': aspects of the man's character which had already been tendered by many others in respect of his political and military judgements.

In a concise and telling judgement Tomlinson wrote that Churchill's writing offered:

[The]... eloquence of an Eton collar on Speech Day. It is intended to impress us; and I doubt whether genuine eloquence ever so intends.

The skill and compassion of Montague's prose impressed him far more; so compelling did he find ‘Disenchantment’ that whilst reading it in an underground train, he 'overshot several stations beyond my destination'. It was a pragmatic, if recognisable, test of quality, and one with which any reader can readily identify. He detected essential 'accents of truth' in the book. It was, he said:

‘...the first and one o f the best essays at recording those years w e have had, or are likely to have. This book will endure.’

Two now virtually-forgotten books of short stories by the French surgeon and writer Georges Duhamel, which had been published much earlier, were also amongst the works most highly prized by Tomlinson. ‘The New Life of Martyrs’ (1918) and ‘Civilisation’ (1919) were, he believed, 'the best fiction we have had out of the war - even in translation'. He also selected the translation of a foreign novel for particular praise, Arnold Zweig's ‘The Strange Case of Sergeant Grischa’, reflecting 'gratitude for a novel which read like that of a master, free, cheerful, and even exuberant'. The Spanish Farm trilogy also earned the same very special gratitude. It was, he wrote, 'masterly in its scope and significance', before adding that the scenes which Mottram realised were a 'rendering of the scene in Flanders (that) is a gift of the gods and we ought to be proportionately grateful ...'.

In considering ‘Undertones of War’ he indulged in a fascinating, if highly elliptical and discursive, analysis which revealed fascinating insights into both Blunden's skill and his own ability to evaluate literature. His conclusion was as laudatory as it was elegant:

‘... Blunden's is a tribute to the unknown soldier more lasting than the poem about a cenotaph.’

Like Seton, Tomlinson dealt an interesting wild card. Tomlinson's was the selection of ‘Field Ambulance Sketches’, written during the war by a lowly corporal, which the critic had first read 'at the front'. It was, he noted, already a forgotten work, but in memorable words reminded his audience that it should not be:

‘thought unliterary to speak heartily of a corporal's sketches of ambulance work because Homer sang of Troy. What is Troy, when we remember Delville Wood?’

The book's detail convinced, he said. It was of the heart. It did not seek to 'improve too much on the simple nature of truth' as, he suggested, did Churchill and those writers who sought to 'heighten and improve' the reality of war.

John Boynton Priestley

B. Priestley's comments seem to have been unconstrained by the fact that he was writing for a promotional book club journal, The Book Society News. The society's book list did not offer mere easy reading for the burgeoning middle class, but included an eclectic mix of largely worthwhile novels, reminiscences and histories. Between March 1929 and April 1932 its Great War offerings and reviews ranged from Compton Mackenzie's ‘Gallipoli Memories’ to Graves' ‘Goodbye to All That’ and from Jack Seely's ‘Adventure to Renn's War’.

In a note on War Books, published in The Book Society's October 1929 journal, Priestly offered his overview of the books on the conflict now 'pouring out'. He highlighted ‘The Case of Sergeant Grischa’ as:

‘Arnold Zweig masterpiece, a tremendous attack upon the inhuman mechanism of the military machine, and, in my opinion, still the best War novel - that is the best exhibition of human nature during the war - that has appeared.’

‘Undertones of War’ he too thought 'a masterpiece', 'superbly written'. Sheriff's play 'which has captured the world' was, he wrote, 'wonderfully truthful', though, like Seton, it seems likely that he was less impressed by the novel based on the play, which Sheriff had written in collaboration with the journalist and broadcaster Vernon Bartlett, for publication in 1930.

Drawing a distinction between authors who protested against war and those who 'honestly attempt to record their own experiences', he provided another, admittedly incomplete, analysis of offerings.

Although Priestly had initially recommended ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ in his magazine column when the book was published in Britain in March 1929, he now aligned himself more closely with those who doubted its merits. Whilst pleased that it had been successful he now thought that:

...its merits, as a piece of writing and a record of the War, have been colossally exaggerated.

In his consideration of the growing number of translations of German works which began to appear he thought that Renn rang true, if 'too staccato and monotonous' whilst Jünger's work he thought 'straight and unsentimental, but with no special narrative'. The anonymous German novel, ‘Schlump: The Story of an Unknown Soldier’ (16) impressed him far more. Although 'an odd narrative', he added that it 'somehow succeeds in giving a more convincing picture of life in the German lines than any of the other works'

Montague's ‘Disenchantment’, Patrick Miller's (The) ‘Natural Man’, Mottram's ‘Spanish Farm Trilogy’ and Max Plowman's ‘Subaltern on the Somme’ (published under the pseudonym Mark Seven) all earned recommendation. He also praised A. P. Herbert's 1919 novel ‘The Secret Battle’, particularly the initial chapters on Gallipoli - where Herbert had served with the Naval Division - which Montague considered contained 'amazingly good pieces of writing'

Whilst George Blake's Gallipoli novel ‘The Paths to Glory’ and J.L. Hodson's ‘Western Front Grey Dawn - Red Night’ earned qualified praise, Priestley's bugbear was Aldington's ‘Death of Hero’, which left him 'quite cold'. It was he said: '... not without descriptive force, but is too ill tempered and conceited'.

Scornful of the personal pretensions which were to dog Aldington's long writing career, he added:

‘... the tragedy of superfin persons, compelled to associate for a season with less intelligent and sensitive men, to take orders from a few jeering sergeants, to get wet and cold and hungry, is of no account, and l for one have no time for this kind of War book.’

Whilst these critics frequently disagreed in their judgements they offer modern readers a valuable reading list and there remains considerable consensus in their opinions. Then, perhaps as now, Blundon, Montague, Mottram and Zweig stood supreme. But whilst the importance of the books of Remarque, Jünger and Renn were clearly questioned they too have lasted; indeed the criticism now seems irrelevant since the popularity of their books continues (even if, in part, a result of general ignorance of over 100 other English translations of German books about the Great War - a number of which are far more impressive than the works of these three authors). Aldington, both as a writer and a man, created mixed opinions and Sassoon, the established, lauded, poet of war, remains a surprising omission.

The fact remains, however, that the reputation of the majority of the books of which these four critics thought highly has remained remarkably consistent. Whilst the term 'classic' is bandied around with undeserved frequency, arguably Seton, Bostock, Tomlinson and Priestly seem to have missed few works of their time which have earned such an appellation. Even amongst those that they damned, with faint praise or direct criticism, there are a number worthy of reading time and shelf space.

Douglas Jerrold

Nevertheless, another, and deeply dissenting, voice should be heard; that of Douglas Jerrold, who after service with the Royal Naval Division, became an established author and journalist and was appointed editor of the influential right wing English Review in 1931. In 1930 Faber and Faber published his outspoken criticism of Great War writing, The Lie about the War, in which he gave voice to deep concern about the way in which 'the reality of war' was expressed in 16 popular war books then readily available in Britain. (18)

Although Jerrold conceded that the books were not necessarily lacking in literary merit, he judged that virtually all presented falsities and fallacies about the war as established and incontrovertible fact. He emphasised that his criticism was not of the individual books, whose 'merits are, in many cases, not referred to' but of:

‘... certain fundamental assumptions about the war which, wholly or partially, are to be found in certain salient passages or incidents.’

In passing, it is of interest that in his later biography, ‘Georgian Adventure’ (19) first published in 1937, Jerrold was to reflected bitterly on the quality of book reviews published in the national press during the late 20s and the 30s (and the elevated comments by established writers deployed on jacket notes by publishers, to trumpet the virtues of the book within). Although he admitted that his own highly effective promotional activities as a publisher had been in part responsible for developing the practice by which publishers sought and placed reviews from established authors on their own lists, and others from writers known to be sympathetic to the subject or the author, Jerrold considered the literary editors on national papers a fairly poor lot. In an interesting side-swipe at Priestly, for whom he seems to have enjoyed no great affection, he also noted that the role of The Book Society, and its reviewers, was commercial, a simple desire to sell books.

Nevertheless, the concern that Jerrold expressed in ‘The Lie about the War’ about the texture of much war writing was not unique; it closely aligned with that expressed in 1929 by the French war veteran and academic Jean Norton Cru in ‘Temoins’ (Witnesses). Employing stringent criteria, Cru condemned much French writing on the Great War which, he judged, failed to offer 'accurate accounts of proven combat experience'. His work, which evaluated the writing of 49 French novelists and 202 authors of memoirs, journals, letters and reflections, was judged to demonstrate considerable scholarship yet earned criticism that he had failed to recognise many quality works of fiction 'which captured the essence of World War I as well or better than some of Cru's choices'. (20)

Amongst the works which Jerrold evaluated were those by Aldington, Barbusse, Blake, Graves, Herbert, Jiinger, Mottram, Remarque, Montague and Hemingway, all of which had been, or would also be, subjected to scrutiny by Bostock, Priestly, Seton and Tomlinson. He concluded that these authors' work, and that of others, largely offered an 'exaggerated' view of a war which he considered 'a great tragedy because it was a great historical event'.

The books claimed to offer, or had been represented as providing, 'ultimate truth' about the war, whilst recording 'every conceivable kind of struggle except the struggle of one army against another' and giving 'the illusion that the war was avoidable and futile'. He further condemned them for half truth; for offering a lie about the war 'without regard to consequences' and for their depiction of 'the mere quality of the slaughter' which he noted accompanied all war, just or unjust.

Above all Jerrold considered that the authors' 'motif’:

‘ ...a picture painted of the four years of conflict as an unbroken sequence of sanguinary, futile and purposeless horrors, debasing its participants, holds the seeds of false doctrine which once learnt, will be unlearnt only at tragic cost.’

In reality, even in what many judge a golden age of war writing, the conflict was too enormous a cataclysm to be captured whole or alive in one great work. Yet, despite Jerrold's view, Bostock, Priestly, Seton and Tomlinson selected a collective of works which are now judged by the majority of readers to offer a 'true' view of war.

Yet, perhaps the last words should be those of Priestly, who first wrote about the rebirth of interest in books about the Great War:

‘I think the great English War novel, taking in the whole thing, from the first enthusiasm to the last bitter stretch, om ittin g nothing, neither the hu m ou r nor the tragedy, show in g how it affected men o f every degree, has yet to be written, and I am not sure that i f it ever will be written.’ (21)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Only one of the books in this bibliography was subject to review by Seton, Bostock, Tomlinson and Priestly. Praise by each individual as denoted by a single +, equivocal praise by + /- and a negative opinion or criticism by - , Lack of a mark denotes a work mentioned in passing or offered as reference.

|

The Book |

Rate |

|

Anonymous, (Emil Schultz), Schlump : The Diary of an Unknown Soldier, London, Martin & Seeker, 1930. |

+ |

|

Aldington (Richard), Death of Hero, London, Chatto & Windus, 1929. |

+/- |

|

Benstead (CR), Retreat: A Story o f 1918, London, Methuen & Co, 1930. |

+ |

|

Blake (George), The Paths of Glory, London, Constable & Co, 1929. |

+ |

|

Blunden (Edmond), Undertones o f War, Cobden Sanderson, 1918. |

+++ |

|

Barbusse (Henri) Le Feu, E Flammarion, 1916. (Published in the United Kingdom as ‘Under Fire’, London, J M Dent, 1926.) |

+ |

|

C ____, (Crofts J HV), Field Ambulance Sketches, London, John Lane, 1919. |

+ |

|

Crozier (FP), A Brass Hat in No-M a n ’s Land, London, Jonathan Cape, 1930. |

- |

|

Cru (Jean Norton), Témoins, Paris 'Les Etincelles', 1929. Nancy, Presses universitaires de Nancy, 1933. Cru (Jean Norton), War Books: A Study in Historical Criticism , San Diego University Press, 1988. (Edited and annotated by Ernest Marchand and Stanley J Pincetl Jr. This edition contains a brief biography of Churchill (Winston), The World Crisis, (Five Volumes), London, Thornton Butterworth, 1923 - 1929. |

- |

|

Doyle (Sir AC), British Campaigns in Europe 1914-1918, London, Geoffrey Bles, 1928. |

+ |

|

Dorgeles, (Roland), Souvenirs sur les croix de bois, Paris, Albin Michel, 1929 |

+ |

|

Duhamel (Georges), The New Book of Martyrs, London, William Heinemann, 1918. |

+ |

|

Civilisation , London, Swarthmore, 1919 |

+ |

|

Edmonds (Charles), A Subaltern's War: being a memoir of the Great War from the point of view of a romantic young mantic youngman , London, Peter Davies, 1929. |

+ |

|

Ex-Private (Burrage AM), War Is War, London, Gollancz, 1930. |

+ |

|

Falls (Cyril), War Books. London, Peter Davies, 1930. (Reprinted with new introduction and additional entries by R J Wyatt, London, Greenhill Books, 1989.) |

|

|

Frankau (Gilbert), Peter Jackson Cigar Merchant, London, Hutchinson & Co, |

+ |

|

Gibbs (P), Realities of War, London , William Heinemann , 1920. |

+ |

|

Gillespie (AD), Letters From Flanders, London, Smith Elder, 1916 |

+ |

|

Grabenhorst (Georg) Zero Hour, London, Bretano's, 1930. |

- |

|

Graves (Robert), Goodbye to All That, an Autobiography , London, Jonathan Cape, 1929. |

++ |

|

Harvey (AD), A Muse of War, London, The Hambledon Press, 1998. |

|

|

Harrison (CY), Generals Die in Bed, London, Noel Douglas, 1930. |

- |

|

Hemingway (Ernest), A Farewell to Arms, London, Jonathan Cape, 1928. |

+ |

|

Herbert (Sir AP), The Secret Battle, London, Methuen & Co, 1919. |

+ |

|

Hodson (JL), Grey Dawn - Red Night, 1929. |

+ |

|

Jerrold (Douglas), The Lie about the War, London, Faber and Faber, 1930. |

|

|

Jerrold (Douglas), Georgian Adventure, London, The 'Right' Book Club, 19387. |

|

|

Jünger (Ernst), The Storm of Steel: From the Diary of a German Stormtrooper, London, Chatto and Windus, 1929. |

+-- |

|

Latzko (Andreas) Men in Battle, London, Cassel, 1930; but first published in the United States as Men in War, Boni & Liveright, 1918 |

+’- |

|

Lee (Mary), It's a great war, London, Allen and Unwin, 1930. |

- |

|

Mackenzie (CMC), Gallipoli Memories, Cassel & Co, 1929. |

|

|

Manning (Frederick), Her Privates We, London, Peter Davies, 1930. (The first unexpurgated edition of Her Privates We, was not published until 1977.) |

- |

|

Miller, (Patrick), The Natural Man, Grant Richards, 1924. |

+ |

|

Montague (CE), Disenchantment, London, Chatto & Windus, 1922. |

+ |

|

Montague (CE), Fiery Particles, London, Chatto & Windus 1928 |

++ |

|

Morris (WF), Bretherton : Khaki or Field -Grey, Geoffrey Bles, 1929. |

+ |

|

Mottram (RH), The Spanish Farm Trilogy, London, Chatto & Windus, 1927. Comprising: The Spanish Farm (1924), Sixty Four, Ninety-Four (1925) and The Crime at Verlynden’s (1926). |

++ |

|

Plowman (Max), A Subaltern on the Somme in 1916, London, J.M. Dent, 1927. |

+ |

|

Remarque (Erich Maria), All Quiet on the Western Front, London, G P Putnam's Sons, March 1929. |

--- |

|

Renn (Ludwig), War, London, Martin Seeker, 1929. |

- |

|

Sassoon (Siegfried), Memoirs of Fox Hunting Man, London, Faber and Faber, 1928. Scanlon (W T ), God Have Mercy on Us, New York, Grosset and Dunlop, 1929. |

- |

|

Seely (Rt. Hon JEB), Adventure , London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1930. Seton (Graham), Footslogger: An Autobiography, London, Hutchinson & Co., 1931. Sherriff (RC) and Bartlett (Vernon) Journey's End: The Novel, London, Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1930. |

+/- |

|

Smith (HZ), Not so Quiet, London, Albert E Marriott, 1930 |

- |

|

Tomlinson (HM), All Our Yesterdays, London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1930. |

+ |

|

Vigilant, psued, (Claud W Sykes). Richthofen, The Red Knight of Germany, London, John Hamilton, 1934. |

+ |

|

(John Hamilton's books were issued undated. Although the British Library lists the publication date of 1934, the actual publication date was almost certainly some two or three years earlier). |

|

|

Williamson (Henry), The Wet Flanders Plain, London, Faber and Faber, 1929. Zweig (Arnold), The Case of Sergeant Grischa, London, Martin Seeker, 1928. |

-+++ |

REFERENCES

- Priestley (J. B.), The Book Society News, London, October 1929.

- Tomlinson (H. M.), War Books: A Lecture Given at Manchester University February l5 , 1929, Cleveland Ohio, The Rowfant Club, 1930.

- Ibid.

- Not least this was the sentiment of John Terraine (discussion with the author) although the term 'closure' was one which was not in his vocabulary.

- Falls (Cyril), War Books. London, Peter Davies, 1930. War Books was reprinted, with new introduction and additional entries by R. J. Wyatt, (London, Greenhill Books, 1989). Like Falls original version, it too has become an extremely scarce book).

- Seton (Graham), Footslogger: An Autobiography, London, Hutchinson & Co., 1931. A Scot, Graham Seton Hutchison MC, DSO, was the first Chairman of the Old Contemptibles, and a founder member of the British Legion. Although he was the Liberal parliamentary candidate for Uxbridge in 1923, in 1933 he founded the pro-Nazi, and anti-Semitic, National Workers Movement. He was believed to be 'a great friend of Hitler' and there is strong evidence that he worked as a paid publicist for the Nazi Party in Britain. See Griffiths (Richard), Fellow Travellers of the Rights, London, Constable and Company, 1980.

- I have been unable to locate a work with this title by the author given. Two alternative works with similar titles seem possible: Roland Rankin's A Subaltern ’s Letters to His Wife (1930) or R. V. C. Vernede's, Letters to his wife (1917).

- Almost certainly Richthofen : The Red Knight of Germany rather than Knight Germany : Oswald B oelcke German Ace, Werner (Prof. Johannes), London, Hamilton, 1933. Richthofen : The Red Knight of Germany was written by Vigilant, the pseudonym of Claude W. Sykes, a highly prolific translator of German Great War aviation books for John Hamilton. He was also an author and former associate of James Joyce, with whom he created a theatre company in Zurich in 1918.

- First published in Zurich in 1918 as Menschen im K reig, Latzko's book was a highly important influence on German and Austro-Hungarian writing about the war. It was published first published in Zurich in 1918. Its translation was published in the United States the same year as Men in War. It was finally published in the United Kingdom in 1930 as Men in Battle.

- Richard Aldington's long writing career was frequently punctuated by controversy. His critical biography of T. E. Lawrence published in 1955, which challenged Lawrence's position as military leader and national war hero (Lawrence of Arabia : A Biographical Enquiry. London, Collins, 1955) became the subject of a major feud instigated by those who had been involved in creating and maintaining the Lawrence of Arabia legend (including Basil Liddell Hart, Robert Graves and A. W. Lawrence). These three, amongst others, sought to suppress, and with considerable success, denigrate, the book; see Crawford (Fred D), Richard Alding ton and Lawrence of Arabia, Southern Illinois University Press, 1998.

- Le Feu was not published in English until 1926, when it appeared in translation as Under Fire. Although the German authorities banned the book, it was read in Germany during the war - both at home and at the front - and greatly influenced a number of individuals who were themselves to write on the war.

- Les crois de boix does not appear to have been translated into English.

- Bostock (J. Knight), Some well-Known German War Novels 1 914-1930, Oxford, B. H. Blackwell Ltd., 1931.

- Sebald (W. G.), On the Natural History of Destruction, London, Hamish Hamilton, 2003.

- Priestly, op cit.

- Although published anonymously, Schlump was written by Emil Shultz.

- The Paths of Glory has recently been described as 'a magnificent Scottish novel' that 'seems to have disappeared into unjustified obscurity' by Robert Price who is currently compiling a bibliography of fiction related to the Gallipoli Campaign (see The Gallipoli , No. 106 - Winter 2004)

- Jerrold (Douglas), The Lie about the War, London, Faber and Faber, 1930. Jerrold was also author of both the history of the Royal Naval Division and that of the Hawke battalion, with which he served.

- Jerrold (Douglas), Georgian Adventure, London, The 'Right' Book Club, 1938. 20. Cru (Jean Norton) Editors Marchand (Ernest) & Pincetl (Stanley J.), War Books, San Diego State University Press, 1988. Harvey (A. D.), A Muse of War, London, The Hambledon Press, 1998.

- Priestley, op cit.