Ep. 178 – Irish Recruitment in World War One – Dr Tim Bowman, Dr Michael Wheatley & Dr William Butler

- Home

- The Latest WWI Podcast

- Ep. 178 – Irish Recruitment in World War One – Dr Tim Bowman, Dr Michael Wheatley & Dr William Butler

Dr Timothy Bowman, a Reader in modern British military history, University of Kent, Dr William Butler, the Head of Military Records, The National Archives, UK and Dr Michael Wheatley, an independent researcher who writes on early twentieth century Irish politics, talk about their latest book, The Disparity of Sacrifice.

This book examines the military recruitment in Ireland during the Great War and is published by Liverpool University Press.

'This is a tremendously important and academically rigorous book, which will come to be seen as a seminal text in the study of Ireland's First World War. It punctures a number of myths about recruitment, and also has significant relevance to wider studies of the Irish Revolution.' Professor Richard S. Grayson, Goldsmiths, University of London

TRANSCRIPT

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:01:17] Gentlemen, welcome to the ‘Dispatches’ podcast. Could you start by telling us about yourselves and how you became interested in the Great War - starting in alphabetical order. Tim, could we start with you?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:01:27] OK, I suppose I became interested in the Great War - as many people do - through history. My great-grandfather served in the Ulster Division, rather an unfashionable Army Service Corps attached to the Field Ambulance. So I knew a bit about his history from an early age. And then, when I was doing my degree at Queen's Belfast, we looked at the Great War and various themes there, and I became aware that there hadn't been, at what stage in the early 90s, there hadn't been much work done on ‘Ireland in the First World War’. So that seemed to be a good idea for a thrusting young academic, as I then was, to get involved.

Dr William Butler [00:02:03] I think I became interested in the First World War completely by accident - and certainly interest in Ireland in the First World War came by accident. I took an undergraduate course on the History of 20th Century Ireland, taught by Tim. I was an undergraduate student of Tim's - and that was the first Irish history I'd ever done as a student. And then progressing on to my Master's, I then came at the history of Ireland and the Great War - in particular from a propaganda angle. That was what my Masters was on - it was on war and propaganda. And again, almost by accident, perhaps by influence, from Tim in particular, is where that came from. And then having done my Ph.D. on ‘Ireland and military traditions in Ireland in the 19th and 20th century’ - obviously the First World War came into that quite significantly as well. And here we are ten, twelve years later and thankfully I’m still able to talk about it.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:03:16] I came much later into academic life - my real fascination has been with political history and in particular with the complete mess that the British political system made of what they called, in the ‘Irish Question’ - and this failure culminated in the only successful armed uprising in the British Isles in the last three hundred years. And the Great War was crucial to this because so many of the events about the collapse of the Union occurred during the Great War. And it was crucial to the transformation of Irish politics. It acted as a huge accelerant of changes that were already there. I come from it, if you like, from the Union being ‘run over by a bus’ - and the bus being the Great War effectively.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:04:09] So why did you write the book?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:04:10] I suppose this is a tricky one. There's a lot of myth making about Irish involvement in the First World War and that is still …. seen in parts of Belfast, where you get the idea that Ulster Unionists rally to the cause of Empire in ‘14/18’ - and this doesn't happen in Southern Ireland. That then was redressed in a pretty major way led by Callaghan and a PhD thesis from Liam Patrick and a series of book chapters. And we were rather unhappy with that rebalance which seemed to put it to the other extreme - which suggested the politics and religion really didn't do this in terms of the issue for enlisting, and also seemed to iron out a lot of the problems between Great Britain and Ireland by suggesting recruitment rates were homogenous in the British Isles. So looking at that, we thought to challenge that interpretation and to reconsider a lot of these range of factors within recruitment in Ireland and Great Britain.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:05:11] Supplemental to that - to say that Tim's absolutely right, that there are these two competing camps in terms of viewpoints about Ireland and the Great War. One of them is that Ireland was some kind of discontented, oppressed colony on the outbreak of war, which was always only a grudging, reluctant participant. This is in complete contrast to the Unionists view of themselves - as totally willing participants in the war right from day one. But there's been a lot of what the Irish call 'revisionist history' since then. And this is the other viewpoint, which is that Ireland has been pretty well assimilated into the British State and that the UK really was more united than not on the outbreak of 1914. In this view, the War and Easter Rising act as a huge, unanticipated accident that blew the Union apart. And I think both views are defective - and an analysis of recruiting is the perfect way to test both views and see how the war changed the course of Irish history.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:06:18] Before we get into the detail of the book, could we start by building some context and look at two interrelated issues: The first is the tradition of Irishmen serving in the pre-war British military and secondly, the so-called ‘Home Rule Political Crisis’ that dominated UK politics before the outbreak of the Great War. Taking the first subject first - what was the scale and involvement of Irish recruitment in the pre-war Victorian/Edwardian Army?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:06:46] If we were to go back to the early 19th century to just before the Victorian period - in the 1830s, it's thought that the British Army was about 40% Irish. And it's thought that’s the sort of figure we're looking at during the Napoleonic Wars. So the idea that Wellington's Army is disproportionately Irish. Of course, then you get the Great Irish Famine and there are fewer Irishmen - is the simple truth of the matter. So those large figures go - but not entirely. There's still a pattern that you can follow through the 19th century of disproportionate Irish involvement. So in 1861, 20% of the population of the UK is Irish, but 28.4% of the Army is Irish. So still disproportionate at that stage - that figure only really settles down in 1911 when the Irish share of the UK population is about 8% and the share of the Army is about the same. So that's quite interesting. You come back to what Mike was saying about that idea of Ireland as a discordant part of the British Empire. You do have a tradition of service in the British Army - and also a tradition disproportionately of Catholic service in the British Army - from what we can work out. If we look at the immediate pre-war period, [19] 12/13 recruitment report, you have 380 recruits to the British army from Belfast - and Belfast is the largest city in Ireland. But from Dublin you have 832. So that there are obviously different issues going on. There are issues of nationality. There are issues of religion. There's also a lot to do with class, which should reflect that Dublin was one of the more depressed cities in the UK, whereas Belfast had a booming industrial base - so job opportunities for men are very different. So you have this pre-war pattern - for regular recruits. Will is better placed than to say more about the Special Reserve. But it's fair to say a very hard time soldiering tradition which is built on. These are important because particularly in rural Ireland, it seems to us that all of these pre-war patterns continue on to the war.

Dr William Butler [00:08:54] In terms of the part time element, the amateur element - in particular things like organisations like the militia, and then from 1998 onwards, the Special Reserve and then also the Imperial Yeomanry during the South Africa War and then the North and South Irish Horse. Really the patterns of recruitment, I think, followed that of a regular army recruitment. What you have, throughout much of the latter half of the 19th century and into the 20th century - leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, is a general decline in this recruitment. And what you have, much like you have with regular recruitment - it's around garrison towns - and those areas that really form the basis of a lot of those organisations and a lot of those units in particular.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:09:56] OK, moving on to the second subject, can you tell us about the 'Home Rule Crisis' and how this shaped the political atmosphere of Ireland before the outbreak of the First World War?

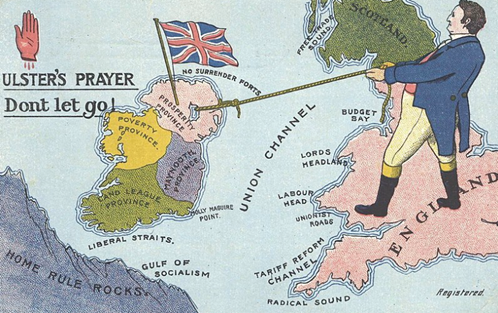

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:10:06] Point one, it's an Irish crisis. It's a struggle between Irish nationalism and Ulster unionism, but it became so pervasive that it infected politics right across the United Kingdom and it led to a bitter political conflict between Conservatives and Liberals.

Specifically, it was triggered by the 1910 general elections, which gave the Irish parliamentary party the balance of power in the House of Commons.

So for the first time in decades, you've got a real chance that Irish self-government, which is basically Irish nationalist, Catholic self-government, is a real possibility. And this crisis lasts right up to the eve of the First World War. So you're talking of a period of more than four years. It is not continuous. It ebbs and flows, but it's marked by rising tension, inflated threats, inflamed rhetoric, and it simply could not be resolved. And what you see, increasing as it goes on, is the resort by both sides to extra parliamentary paramilitary activity and specifically Unionists who claimed that there were effectively no limits. There’s a famous phrase by Andrew Bonar Law on what they would do to stop Home Rule. In 1914, in the spring of 1914, a significant part of the British military stopped conniving outright disobedience of lawful government orders. This is known as the 'Curragh Mutiny'. And by the summer of 1914, nearly 300,000 Irish were members of rival, partially armed political militia. These are the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Irish Volunteers. So it's basically a mess. And the fault lines on Home Rule just make the general fault lines in British politics wider and wider, because this is the period of what's known as the struggle between the 'Democracy' with a capital 'D' and 'privilege'.

So this is a period of class conflict, industrial unrest, the challenge of labour, and, of course, the bitter and violent conflict over the question of the wider suffrage - both the suffrage in general and women's suffrage. So it's anything but a period of an 'Edwardian Summer'. And of course, nothing seemed to be able to lance the boil. On the eve of the Great War what you have is yet another attempt to broker a compromise that fails. And it's held in no less a venue than Buckingham Palace.

You also have a situation in which, what the Irish would call 'English troops' - they were actually the King's Own Scottish Borderers - had just 'murdered', in inverted commas, three Dubliners in a shooting in Dublin. And many, many thousands of Irishmen are still drilling and training and arming themselves. So that's the situation that you have right up to the outbreak of the Great War.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:12:55] Archduke Ferdinand is murdered. We all plunge into the war and it in a way intervenes on this domestic crisis that's happening in Britain. And Irishmen respond to the call for volunteers. What was the level and nature of that response across these two communities you've already talked about?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:13:14] Well, of course, on the outbreak of war, we end up with initially the recall of Reservists. And that all goes forward as normal, as had been planned, whereas there have been thoughts that Carson, in particular, would try to frustrate that. So that is an important move on the outbreak of the war. After that, we get a lot of recruitment that is deemed to be non-political. There's a thought that you get very large numbers of unemployed men in Dublin that enlist in the Irish division - and the politics takes some time to play out.

Politics becomes very important in recruitment, but it takes time to play out.

So it's not until a full month after the outbreak of war that you start to get formed Ulster Volunteer Force enlistment into the British Army - into what's to become the 32nd Ulster Division. And that is very impressive when it starts off in Belfast - it starts off in Belfast, 4th September, and goes through really until the September with different UVF threats on designated certain days - so in one week of that period, there are almost 5,000 Ulster volunteers that enlist in one day. In fact, on the 6th of September 1914, Belfast had the highest recruitment in the UK. So these volunteer forces can't be overlooked, but that's not mirrored elsewhere. And Ulster, in rural parts of Ulster recruitment rates from Ulster Volunteers aren't so high - that's particularly noticeable in Fermanagh. And there are a lot of concerns there, about the nature of the home of the settlement. A lot of Unionists think that Home Rule is still going to be enforced at some point during war because it's brought through that mid-September 1914. But then there's a delaying clause. A lot of Ulster volunteers don't believe the arrangement will hold. They think that if the British army is [ ]There's a few other factors that I should say, to do with Belfast, particularly. We think of Belfast as a very big industrial city, but it sees a lot of layoffs at the outbreak of war. So the shipyard, Harland and Wolf, which was used to making what [ ] liners at seeing that the move for those during the war to what's on the stocks is mothballed. Harland and Wolf, has that kind of reputation of building military royal naval ships. So a lot of men are, in effect, unemployed. So some of those that we would have thought of as the 'aristocrats of Edwardian labour', very well paid shipyard workers, are self-unemployed and it seems a fair number of them that [enlist].

The nationalist response is an interesting one in Ulster, because it comes later than the Ulster Volunteer response. There's a lot more negotiation carried out by John Redmond and other nationalist followers before they feel that they advocate enlistment in the British Army and this is largest into the Irish 6th division, which has a British [ ] for Irish national volunteer. So we get formal recruitment there and West Belfast, where we get about 1,050 recruits from the Irish national years over, effectively a four month period and to the 6th Connaught Rangers who usually are associated with the west of Ireland.

And that then means that Catholic nationalist recruitment West Belfast is second only to Protestant unionist recruiting in other parts of Belfast. So Irish National Volunteers, Belfast are a lot more likely to enlist than Ulster Volunteers in parts of the Province. So that's an important caveat to put in there.

The Belfast enlistment is largely down to seeing the activity of Devlin, MP for West Belfast. We then got recruitment in Derry City amongst Irish national volunteers pushed by Charles O'Neill - a former soldier himself who had served in the Guards and as a figure in the Irish National Volunteers there. And then in Enniskillen, we've got a fairly small contingent of about 67 Irish national volunteers that enlist there led by John Wray, who's the son of a lower [ ] figure and the Irish nation volunteer. So there's a lot of localised activity and it's only in Ulster that we see this form of Irish National Volunteer Recruit.

The limits of this volunteer recruitment are really seen by about the spring of 1915. The last hussar formally, I think. we can identify - is to do with the formation of some of the Reserve battalions for the Ulster Division. After that, things settle down into a pattern that looks a little bit like pre-war. So we got a large spike in the autumn and the spring of 1915. And then things settle down very markedly after that. I'll turn to Mike to say more about the south now.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:17:50] But it's a bit of a paradox, really. A lot of nationalist politicians who were recruiting talk about the 'miracle' because of Irish nationals recruiting in the Great War. But the paradox is that at the same time, they were giving speeches - all the time, denying charges that recruiting was mediocre. And you saw a very brisk upturn in recruiting on the outbreak of war - hugely higher than pre-war levels. There's no doubt about it that the depots saw very rapid turnover of men coming in and being processed and joining up. You also saw a very prompt and swift mobilisation and call up of Reservists. There were 30,0000 Reservists in Ireland on the eve of war. And not only they swiftly called up and they all joined up, but they cheered and paraded with bands on their way to war.

The overwhelming consensus, almost right from the outbreak of war, is that Germany is the villain, the aggressor, and that France and Belgium and England are the allies and deserve support in the war. So there is a very, very strong, overwhelming pro-war consensus - pretty well right across the island of Ireland, I would say. And you get profuse support activity - comforts for the troops, funds being raised for the troops' dependents, homes being found for Belgian refugees, volunteer nursing is booming in Ireland. And there's no naivete about the war - it's seen as a terrible event and there's no real sense of naivety that the war's going to be over terribly quickly. The idea in Ireland at least, that people thought it was going to be over by Christmas is another myth. The other thing is, just as in Ulster, you get huge early economic disruption, particularly in the towns in unemployment and short time work.

Don't forget, there's been a major financial crash right across the UK from the end of July onwards. So that in itself, as Tim mentioned in Ulster, is a big spur to recruiting. So that's the 'miraculous' side of things. The 'mediocre' side of things, is that the numbers are really not that huge. And by the second week of December, the War Office is issuing a statement on behalf of Lord Kitchener nonetheless that recruiting into the First New Army Division in Ireland is pretty piss poor. And I think if I remember, Tim if you had the numbers years ago - the 10th Irish Division, I think it's up to about 5,000 men by this state, which is roughly 40% or a third of comparable levels for a UK New Army Division. And the War Office statement says, if you don't fill this Division, we're going to have to fill it with non-Irishmen. And that gets a huge amount of press coverage in Ireland in the middle of September.

In the south and west, the mould is not broken. You get a lot more recruiting than you had before the war, but it's a lot more of the same. Politics basically gets in the way. In the first six weeks of the war, the Irish Party and John Redmond, who dominated Irish politics in the South and West - were simply not prepared publicly to advocate recruiting into the firing line until the Home Rule Act got the Royal Assent. And that's finally achieved in about the 14th, 15th, 16th of September. And then Redmond comes out very strongly pro-recruiting.

Absolutely, no doubt the words are absolutely unequivocal in terms of being pro-recruiting. But the deeds of his organisation are not to promote recruiting, but to stage a putsch effectively and take control of the Irish Volunteers - the big nationalist paramilitary organisation. There are meetings all over the country at which volunteer companies and regiments are literally packed by the Irish party and their opponents. Anti-war opponents are kicked out - and they're called recruiting meetings and in theory, they're supporting a pro-war pro-recruiting policy. But all the time, the Irish politicians who are leading this operation say we are doing this to secure unity and loyalty to our leader, Redmond, and we are not acting as recruiting [ ]. They use that phrase all the time.

So you don't see a huge upsurge in recruiting after the Home Rule Act is past. You actually [see] recruiting rates fall in the south west after the Home Rule Act is past - and by the end of 1914 recruiting in the south west has tailed off, by quite an appreciable amount. And it stays pretty inadequate right the way through 1915. There are a couple of big fillips upwards when the War Office and other organisations finally get their act together. And there are two very determined recruiting campaigns - official ones - in the Spring of 1915 and in November 1915, but they are very short lived, there's no follow through - and by the end of 1915 you're running at - well - at the beginning in 1916, about 1,500 a month, which is way below the necessary level to keep the Irish Regiments 'Irish' - and almost flat line.

In Ulster, recruiting went up like a rocket and down like a stick - [while] in the south and west the trajectory is a - a steep upsurge, but nothing, nothing like as much as in Ulster and then a rather dreary, gradual decline to very low levels by the end of 1915.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:23:18] For those who actually joined Kitchener's Army, what was their motivation for enlistment?

Dr William Butler [00:23:23] I think, of course, motivations varied widely person-to-person, just as they did in Great Britain. And obviously, Tim and Mike have teased out some of these issues already in terms of economic necessity. But we can also point to things like a sense of adventure or patriotism - as broad reasons.

If you look at some of the recruiting posters, actually, which were specifically designed for Ireland and its situation - because a lot of posters were created or adapted to suit the specific circumstances in Ireland, they often point to at least an attempt to try to tap into genuine concerns in Ireland at the time. So you've got images, especially in some of the earlier places for the early 1915 campaigns - that look at things like the plight of Catholic Belgium and posters that talk about this is a quote that 'the hundreds of desecrating and destroyed the cathedrals of France and Belgium. Irishmen do your duty'. But we also have things like 'Is your home worth fighting for?' 'It'll be too late to fight when the enemy is at your door'. And again, these are similar themes that you see across all of the United Kingdom, really.

Then you have other really specific posters which draw on the circumstances in Ireland. So there's one which looks specifically at the farmers of Ireland 'Join up and defend your possessions' - that's really tapping into that - lack [or] certainly perceived lack, at this point of recruitment in rural Ireland - that the numbers are almost negligible in a lot of areas. And these - things are tapping into that. Certainly officials are attempting to tap into that.

You also have things that emphasise Ireland's military heritage. And Tim obviously already talked a lot about - and spoke a lot about - the Victorian and Edwardian periods in that context, and in particular depicting the four nations of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England working as one - and often actually at the front, you know, you'd - say, ‘come and join us’. And it's this real idea of teamwork across the four nations there - and actually just picking up on this idea of filling Irish Regiments with English recruits. There is even one poster that exclaimed, 'Irishman, are you going to like famous Irish regiments to be filled with English recruits because you have not yet joined them? Avoid this and keep these splendid regiments Irish.' So you really get this idea of - some of the propaganda and the authorities tapping into what is being said on an official level and ... then how they are trying to to tackle these lower recruitment levels on the ground as well.

Dr Tim Bowman [00:26:24] There are a couple of things I wanted to say a bit more about. One is to do with military traditions. That you do get families with very firm military traditions. And you see this in some of the early casualties: Gallipoli, Retreat from Mons ... You get sergeants killed and it's obvious that they're the third or fourth generation of their family in that regiment. So there's certainly that to be built upon.

The other bit we might say a little bit more about - the politics - where volunteer forces leads men. If you're looking at round figures it's about 30,000 Ulster Volunteers who join the British [army] or thereabouts]. So that's 30,000 / 31.000 tops at the outside - and for the Irish national volunteers its a very similar figure - somewhere 30,000 to 31,000. But of a force of about 180,000. And we can say something about how the politics were dealt with there.

Edward Carson, when he's talking to men enlisting - Royal Ulster Volunteers [ ] - is very clear with them about the settlement they got over Home Rule, isn't something very celebratory, but he says to them that the Empire goes down ... [is going down?] ... and says that Britain's difficulty will not be resolved in a day ... and that Ulster Unionists are part of the British Army. So he's quite upfront with men and [sort of takes inspiration from them].

Some Irish nationalist politicians are less straightforward on this.

The Unionist Press has a field day when Joe Devlin says to a Belfast Regiment of Irish Volunteers, that effectively Home Rule is an established fact. And that British democracy through nationalists now denies Irish legitimacy. And of course, the Unionist Press says, 'yes well', this completes the settlement of September 1914. Nobody should [be going to war?] So some of the politics is very [easy/hard to say?]

And you then perhaps have [you have to think?] this culture of Unionism as they see it [ ] but within the whole lot of ... these recruits are making up 6,000 of about [100,000] Irishmen who serve in the British Army during the First World War. So we shouldn't let the politics take over our analysis of that.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:28:21] OK, so how did recruitment in Ireland in the first half of the war compare to the rest of the United Kingdom?

Dr William Butler [00:28:28] I think as we've already alluded to, in short, the numbers you're looking at for Ireland are much, much lower. As in England, Scotland and Wales you have the peak of recruitment in September of 1914. And again, as Tim already mentioned, in Ireland, that's predominantly down to things like the UVF recruitment campaign, but also, as Mike mentioned, what's going on in the south and west then as well. And I think the fact that any propaganda machine or any in Ireland doesn't properly get going across the country until the first few months of 1915 doesn't actually help that. And even when this is set up, you get these short bursts of pick up of recruitment. But the numbers are still much lower than in Great Britain as well. And as part of the book, we put together a full statistical monthly breakdown of recruiting numbers for each of the recruiting districts across the United Kingdom. And these are tables there, they are handwritten tables that are available from the National Archives in Kew, which starts in August 1914, and ends with the introduction of conscription in Britain in April 1916. And they clearly demonstrate this stark difference. And again, we've got a few accompanying graphs that really demonstrate this in quite a visual way as to just where Ireland sits in comparison to the rest of Great Britain.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:30:01] One of the crucial differences between Ireland and Great Britain is that Ireland is a vastly more agricultural economy - and the proportion of the population who derive their living from agriculture was over half at the turn of the century. The proportion of people who derive their living from agriculture in Britain was way below 20% - so it's much more rural - and agricultural recruiting was bad and below average across the United Kingdom. So if you're much more rural, you're going to have a much lower recruiting rate in Ireland than in the rest of GB. That applies right across Ireland as well. So that rural recruiting is derisory in the south west of Ireland and it's derisory in unionist Ulster as well. So this as a demographic, economic factor, completely overrides.

And the other thing is the recruiting of farm workers in Ireland is lower than recruiting of farm workers in Great Britain because there's a vastly bigger proportion of small family or quasi-family farms in Ireland than in Britain. And the proportion of farm workers who are farm labourers is much lower than in Britain. And it is farm labourers who tended to join rather than farmers or farmers’ sons or farmers’ relatives. So you've got this lead weight on recruiting in Ireland right through the war. And it's almost inescapable.

And as Will has said earlier, they try and make specific recruiting appeals to Irish farmers. They're almost wholly ineffective. And don't forget there's a boom in farm incomes and demand for farm produce right across the UK and the demand for more labour intensive tilling. So if anything, the shortage of potential farm recruits gets greater as the war goes on.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:31:48] So what was the impact of the Easter rising on recruitment from 1916 and how did they shape the pattern of recruitment in Ireland for the rest of the war?

Dr William Butler [00:31:58] So, again, as Mike mentioned, recruitment in the whole of Ireland had pretty much flatlined by February 1916 - fewer than 1,500 recruits are forthcoming in most months by this point. And that had been the case for quite a number of months - apart from when the second organised recruitment campaign occurred in November 1915. And really, the Easter rising does little to change that. And I think initially when we discovered that the three of us, we were quite surprised - that there's no noticeable difference in numbers. And really these - numbers, the 1,500 a month or around about that last until August 1918. So right through 1917, that's the case. And also through the back end of 1916 and into 1918. And then again there's a jump, a very small jump in August 1918 when the Irish Recruiting Council was formed as a last ditch attempt to stave off conscription in the summer of that year. And again, no official recruiting machinery had existed since at least the beginning of 1916 anyway. So in some ways the low numbers are also hardly surprising. The officials aren't taking this seriously. And this was also a conscious decision, particularly after the Easter Rising to just stop this official machinery from carrying on.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:33:32] OK, I would just add to what Will said in a couple of respects, he mentioned that the official recruiting effort effectively stopped after the Easter Rising. They don't want to do anything that's remotely sensitive. But the Easter Rising has a huge impact on Irish politics because it effectively leads to the effective complete destruction of Irish constitutional nationalism and a rebirth of much more aggressive anti-war, anti-recruiting Sinn Feinism. And you get the collapse of the Irish Party. So the Irish Party in no way advocates recruiting after the Easter Rising, but at the same time and the Irish Party is collapsing, leaving a vacuum in Irish politics filled by Sinn Fein. And what's interesting is the fact that there's no official Irish nationalist support for recruitment - and the fact that there's no official recruiting campaign now worth its name - has very little impact at all on recruiting numbers, which were already low and just dribble down a little bit more. So it makes me think, to just realise how ineffective official recruiting and Irish Party support for recruiting had been - at least in 1915. The other thing about these Easter Rising that's interesting is that you don't see a significant falloff in people going over to Britain for munitions work or general war work. So there is still a great deal of practical support for the war effort going on after the Easter Rising. And you see munition workers going backwards and forwards across the English Channel. You see the support funds, the charitable funds, the nursing organisation still being supported. And there's quite a lot of survey evidence in Ireland, mostly by the police, at the end of 1916 about what is the general state of public opinion and support for the war - and the broad fallout from those surveys is - support for the war is still there - support for serving soldiers is still quite large. Support for the Army, as an institution, has become much more ambivalent and patchy. And in parts of the country, there is a distinct sense of, at best, indifference and rhetoric against the Army - particularly because of its role in the executions after the rioting and the mass arrests after the Rising - is definitely waning.

Dr Tim Bowman [00:35:53] I was going to say a little here thinking about the sort of Ulster focus, we can say that the impact of the Easter Rising being somewhere [ ] the limits of the Ulster Volunteer Force, when the Rising breaks out an Ulster Volunteer attempt is made to mobilise the support of the British government. And it seems that the numbers, the turnout can be effectively mobilised [ ] So the Ulster Volunteer Force, that was about 100,000 strong in the summer is then [ ] You can think, of course, of Easter 1915 where the Belfast Regiment of the Irish National Volunteers had led a large Irish Nationalist parade in Dublin [ ]. They were saying they had the best recruiting record of any of the [regiments]. [ ]. So while the police reports still list Irish National Volunteers, Ulster Volunteers throughout the war, and suggest that these are still there - they really had petered out before the Easter Rising.

If we think about the situation in Ulster. You might think about two other things. One is the Battle of the Somme. Of course, tradition takes [ ] killing and wounded. And that's seen to lead to a couple of officers [ ] my life [ ] The other can [ ] so there are on. Of course, the economy in Ulster very rapidly turned to war work. So you get shipping orders from the Royal Navy of a [ ] ships, [ ] cargo ships that are ordered and you [ ] going over warship production so that's work patterns are [ ].

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:37:28] However, we still get a small trickle of men still joining the British armed forces in the later part of the war, certainly from 1916 up to the Armistice. What was their motivation for joining?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:37:40] OK, well, it's not and somewhere such a small trickle, we are still looking at [ ] so part of peace time recruitment at [ ] but of course not [ ] that are brought in by [ ] .

The motivations are a little tricky to work out. I tend to end up in this rather difficult system that Will has alluded to, where you're looking at recruiting propaganda and working out that this must have had some impact on men's decisions - didn't it. If that's the case and I think that there is an argument for it, then we can say that as the war goes on that there is an increasing push for men to enlist in more specialist units, typically things like the Royal Air Force - with an idea that they can learn a trade - so that this is quite a well [ ] they will come out skilled [ ], whatever. There's also the issue amongst that of being in the non-combat units. So a lot that is pushed is that if men join the RAF, that they will be ground crew behind the lines and can't be compulsorily transferred to the infantry. So there's an attempt to do that. Some elements are there are about enlistment - the Royal Navy, there's some quite interesting newspaper ads that talk about what a man's [life’s like] for those of the Royal Trawler Section, which is all to do with minesweeping in coastal waters round the British Isles. So some of these are pushing very different messages from what is [ ] . Having said that, you still get the call for enlisting in the historic Irish regiments - and there are still tugs at the heartstrings about the traditions that go back. So there's one about Spain and the Royal Irish Rifles. Let's bring this back to the military hero of the 18th century period, what that did for sure, but also to talk about the glory to the nation and how they are being forced to. There's a number of [ ] that are going on there [ ] on the war.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:39:30] Can I say something - this business of the RAF - there was a big increase in monthly recruiting rates from August 1918. And that's very linked to the beginning of active enlistment into the RAF as a separate service - which only began in Ireland in July of 1918. And in the three months where you get this big increase in recruiting, over around two thirds of all enlistments are into the RAF. And the campaign to get people to join, as Tim said, is absolutely about acquiring a trade, getting a skill, not being in danger, not being conscripted, not being transferred to the army, etc. And they plan the campaign exactly on that basis. Of course, there's an element of the romance of flying as well, and they try and get aeroplanes to fly past recruiting - this kind of thing. But the real recruitment into the RAF in that period is absolutely in the sort of non-combatant ‘get a trade’ role - and it works. And it works on the same basis as the official, what was called the ‘war munition volunteer scheme’, whereby if you went to work officially in this scheme in England - in munitions work - you could not be conscripted in England while you were in England. And again, that's a very good way of getting Irishmen to support the war effort - the actual rate of army recruit at the end of 1918, barely shows - It just carries on with that low monthly rate of between 800 and 1,200 a month. It just doesn't register on the radar as a significant change.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:41:04] So in 1916, conscription was introduced in England, Wales and Scotland, but not Ireland. Why was this so long ago?

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:41:14] Conscription is a major recurring theme, or fear of conscription, throughout nationalist Ireland almost from the beginning of the war. And there is, in fact, a small panic about the likely introduction of conscription as early as October 1914.

There was an old act called the ‘Military Ballot Act’ that it was rumoured was going to be reactivated to pull men into the army. And it's a load of baloney this, but it leads to several hundred men hastening rapidly to Queenstown to get on a boat to go to America to escape it. And again, a lot of press comments and derision of these men at the time.

You get another [lively] scare about conscription at the time of the formation of the Coalition Government in May 1915. And again, absolutely building up to the introduction of conscription from October 1915 onwards, right through to January 1916, - a huge amount of discussion, debate about whether conscription is going to come in.

And there are two absolute recurring themes in Nationalist circles about conscription right from the beginning of the war. One is, if you don't enlist voluntarily, if the voluntary system doesn't work, then we're going to get conscription - and that's going to be terrible. And the second one is the imposition of conscription on Ireland when it has not yet been granted operating Self-government is an outrage - and will break the consensus that has been formed and will lead to resistance right across Ireland.

And this view is expressed right across the spectrum of national opinion by Irish parties speakers, even at recruiting meetings, they'll say it. And It's accepted effectively after months of lobbying by the government. There's the parliamentary occasion when Bonar Law gets up on his feet in Parliament, I think at the end of 1915 and says "if we introduce conscription in Ireland, it's going to lead to resistance, and is going to lead to a sufficient diversion of military resources simply to enforce conscription." So there was a recognition for most of the war that conscription could not be imposed on nationalist Ireland and that it would create more damage than it was worth.

It finally breaks down in 1918 with the Ludendorff Offensive when the British government has radically to increase the range of people conscripted into the UK armed forces. And the belief is that unless they introduce conscription in Ireland, they simply will have almost a mini-revolt in British public opinion. Why on earth should we draught an older man, more married men, etc. to do this when the Irish aren't even conscripted at all? And so they announce - and rush through the introduction of conscription in Ireland at the beginning of April 1918. And there is uproar in Ireland ... and there is an Irish nationalist version of the Ulster Covenant: the Church, the Irish Party, what's left of it - Sinn Fein totally united - massive fundraising, membership of the new Irish volunteers - the precursor of the IRA shoots up - and there is a series of, well, a one day General Strike as well. And within a fortnight, the government backs down. It realises it's got a complete hornet's nest and announces that they will defer the introduction of conscription if Ireland can't produce sufficient recruits in a six month period.

And so you get this huge hornet's nest stirred up called the 'Conscription Crisis' in Ireland, and then [ ] it sort of subsides and you move back. What it did do was absolutely cement Sinn Fein as the leader of Irish nationalists opinion for the forthcoming years. So conscription is this theme right through the war - you get this final panicky crisis in 1918 - and then it becomes effectively a complete non-issue as far as I understand.

Dr Tim Bowman [00:45:15] Yes, I mean, [ ] to think of the practicalities a little more. You'll be aware of the sort of idea that the British [ ] [ ] [ ] did during the First World War. But the conscription system, as happens in Great Britain, relies on a lot of localism and relies on military service tribunals to strain those objections. Of course, these aren't all conscientious objectors as we think often. These aren't people saying like [ ] men saying, well, I'd love to go and fight in the Great War, but I'm a widower with three children to bring up or I'm running the shop by myself - and this is what goes on there. What we get with these local tribunals is normally local councillors, trade unionists, retired army officers. It's clear in Ireland that system just can't work. Irish parliamentary party representatives are not going to sit in these tribunals. The labour movement is not going to sit on them. The military officers who might be prepared to vote will be utterly [ ]. So what would be [ guessed? ] would be a very harsh, compulsory system. Bringing back some of the sort of - the British colonial style conscription system.

And frankly, a lot of those in the Dublin Castle administration, British army [ ] Well, given the amount of troops and police that are going to be needed to enforce all of this, it's better just to leave things as they are - that is [ ] the numbers that came into the army. Well, how could they be dealt with by the [ ]? [ ] fall in line. Would they be put on the non-combatant defence rules where they were anyway? So really, the Army takes it as just too much hassle.

There's also a danger exposing the two Ireland's in that Ulster Unionists generally say they're in favour of conscription. This is at least as what's said publicly behind the scenes they are saying, well, you know, the number of our supporters have already enlisted - and the number that are in our industries or agriculture means that wouldn't be affected by this anyway. But there looks to be this terrible danger that you will get a conscription system that will look on the surface as working in North East Ulster and wouldn't work anywhere else in the country and not with them be a precursor to [ ] settlement. So that's all seen as incredibly messy by the British government.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:47:30] Two areas that are not often considered in the context of Irish Recruitment during the Great War are the recruitment of officers, and secondly, the recruitment of Irishwoman into military services such as the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. Could you tell me a bit about each? Can we start with officers?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:47:45] OK, if we're looking at the Officer Corps, it's a bit tricky to work out just how many Irishmen served in the Officer Corps [ ] in somewhere. If you have somebody who is Irish but is being educated at a public school in England [and therefore has a British address?]- it's not obvious that they are Irish. And, of course, they can be posted to any regiment in the army. So that's quite tricky. And in round figures, we're probably looking at 8,000 Irishmen who served as officers during the First World War.

There are a number of aspects to look at : before the First World War there was a tradition of the Anglo-Irish gentry serving in the British army. This is more familiar to many people - if they were the [Ulster Field Marshal, they were and son one]. They were all serving officers in the First World War, of course. That can be overestimated. It is probably in the case that the Anglo-Irish gentry were going to be roughly a portion of their share of population. But that's certainly a long tradition in some families. I think with [Coopers? ] have something like 26 male members of the family serving in the First World War. So there's obviously family traditions dealt with by some of the gentry families.

Before the war the Territorial Force generally hadn't been extended to Northern Ireland or [ ] Ireland. Full stop. But it had been in terms of Officer Training Corps units being set up. Now, they were established for schools or colleges for children as well, Belfast, two schools in Dublin have some and Cork Grammar School and also Trinity College, Dublin, Queen Belfast Royal College as well. So there were Officer Training Corps before the war that had served where they should be advising the outbreak of war.

There's then the sort of political commotions aspect, which is particularly in evidence with the Ulster Volunteer Force, where a number of men either are sort of acting officers and in the Ulster Division camps in September or actually enlist in the ranks, but serve as acting officers. And they then get their commission confirmed in most cases in August. So these are men who have often brought in a certain number of volunteers with them or have been [ ] within the Ulster Volunteer Force.

We get a small element of national volunteers as well. John Wray, who had I mentioned at Enniskillen, he gets a commission - Captain for bringing in the 60s south crew. But then with the innate sensitivity that we would expect from the War Office, he's packed off to the King's African rifles so as not used further and recruiting. Somebody in the First World War who ironically, ends up at regiment depot of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers 38th / 39th managing recruitment there. So funny how [ ].

As the war develops the Inns of Court Regiment, which is essentially an Officer Training Corps unit, sets up a recruiting base in Dublin. There's a pretty large number of [ ] get commissions that is also played on after the 'Inscription Crisis', when a lot of the advertising that comes out talks about Irishmen being able to ask for officer training - so this idea they wouldn't want to serve in the ranks of someone from the class background, so the officer route, as opposed to in a way which of course, wasn't really open to conscripts.

So there are different sorts of paths there that are followed by officers, and there is a danger of double counting because, of course, some men enlist in the ranks, serve for a period of months or years and then were promoted as officers. So there's actually kind of journalists and recruits formally that way [ ].

In terms of female recruitment, we didn't really have a great deal on this in the book because the figures are elusive. But since the book went to press - 'Disparity of Sacrifice' - a new book has come out by Barbara Walsh, which I would refer people to - 'Irish Servicewoman in the Great War'. Barbara's work is as interesting, deeply researched, - and it shows us the limits of the records of the First World War. She can identify 400 Irish women who enlisted. And what was Queen Mary's Auxiliary Corps.

Two things to say about that - the first is that as with the lot of the male service records - a lot of these service records were destroyed in the Blitz [ ]. So the number was undoubtedly higher than 400, at least double, I would think possibly we could factoriese of that by 5 or 10. There might have been 5,000 Irish women who served in the British [ ] . The other side is to say that Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps - rather says it all these women are not enlisted as soldiers. They are listed as auxiliaries and do not have combatant [ ] clerical jobs, typewriting, cooking, cleaning. Many are not very happy that they find the opportunities, different lives and being pushed back into the very domestic sphere of cooking and cleaning - so the female recruitment is fairly limited.

There are clearly drives and I think references things in Ulster where you get Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps parades in places like Bangor, Lisbon - which are then targeted purely on recruiting women. But the Queen Mary's Auxiliary Corps does not organise specifically an Irish company. So women are then spread throughout the organisation, which again makes it very difficult to establish exact numbers coming from Ireland.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:53:02] And finally, gentlemen, where can people learn more about your research?

Dr Tim Bowman [00:53:07] Well, the book is available from ‘all good bookshops’ - as the phrase goes - and Liverpool University Press direct. There should be copies in libraries in Northern Ireland in due course. Covid is creating various problems there and otherwise you can look at our free university websites. And websites on the National Archives.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:53:28] And I must say it is available for Christmas as we are approaching the festive season.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:53:36] The ideal stocking filler! Yes.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:53:39] Gentlemen, thank you very much for your time.

Dr Michael Wheatley [00:53:42] Not at all, thanks a lot.

Dr Tom Thorpe [00:53:48] You have been listening to the 'Mentioned in Dispatches' podcast from The Western Front Association with me, Tom Thorpe. Thank you to all my guests for appearing on this edition, the theme music for this podcast was George Butterworth's 'The Banks of Green Willow', it was performed by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, conducted by Chris Russman and produced by BIS Records. This recording is part of a collection of orchestral works by Butterworth, performed by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and supported by The Western Front Association. This is available from all good record stores under the record code BIS 2195. Until next time.