A brief history of IR 63

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A brief history of IR 63

The 63rd Silesian Regiment was a unit of the German Imperial Army during the First World War. It was part of the larger Silesian Infantry, traditionally recruited from the Silesian region of Germany, which was then within Prussia and is now located in both Poland and Germany. The regiment fought on both the Eastern and Western fronts during the war.

The following history of IR (Infanterie-Regiment) 63 comes to us from Matteo D’Angella.

63rd Silesian Regiment assault tactics 1914-17

The 4th Upper Silesian 63rd Infantry Regiment was formed on 5 May 1860, with its headquarters in Oppeln (present-day Poland). In 1900, some soldiers were deployed to China. On 2 August 1914, the regiment was mobilised and sent to the Eastern Front. The following day, Silesian troops had their baptism of fire at Czenstochau, where they repelled the 14th Russian Army Corps, including Cossack cavalry.

The IR 63 remained on the Eastern Front until 6 August. They would have to wait three years to return.

The regiment moved to France, and by mid-September 1914, following the Battle of the Marne, they were engaged in static trench warfare along the Beine-Nauroy-Sillery-L’Esperance Farm line near the well-known Fort de la Pompelle.

Notable early actions and tactics

On the night of 7–8 December 1914, Polish legionnaires in the French Foreign Legion sang their national anthem and encouraged the Silesians to defect. The response was hesitation followed by rifle fire, resulting in the death of the soldier Władysław Szujský.

In January 1915, IR 63 began sending patrols into no man's land. From these patrols probably came the unit’s first Stosstruppen (shock troops).

They felt themselves ‘rulers’ of the battlefield. So much so that on the night of 15 January, when a squad from 3rd Company was patrolling, they came across German dead from the first months of the war and stopped to bury them in an abandoned trench. The dead were men of Infantry Regiment 92 (Duke of Brunswick) – one officer, one sergeant major and eighteen soldiers. The officer was probably First Lieutenant Otto Leonhard von Bornstedt, 11th Company, killed on the 18th September; the NCO probably Sergeant Major Friedrich Hüser, also 11th Company, killed on 13th September 1914. Today these men lie in a mass grave in Berru German War Cemetery.

The regiment undertook more aggressive assaults in the Champagne region, near Hill 196 and Bois Elongé near Ripont, counterattacking at company level French infantrymen and chasseures à pied. One of the first Stosstruppen was Gruppe Dentler, named after its daring commanding officer, known throughout the regiment for his boldness.

Spring developments and the Somme

By spring 1915, German troops formed small, lightly equipped platoons that discarded helmet spikes. During this period appeared the first Model 1915 Pickelhaube helmets, fitted with the grey eagle and removable spike. But evidence that the Model 1895 Pickelhaube was also worn without the spike is found in a letter owned by collector Jan Willem Kooistra. In the letter, Private Fritz Limbach of the 6th Company of IR 16 wrote that M1895 spiked helmets were worn without spikes at Auchy les Mines (Artois) in April 1915. That seems common for this period of war. An even earlier source is a photo taken near Rawka, Poland, in February 1915.

Although the stormtrooper raids were feared, they were not always successful. The night of 27 July 1915 proved traumatic for the attackers when they met fierce resistance along the railway near the sugar factory at Souchez. The Silesians were pushed back by French Infantry Regiment 237 in a hail of hand grenade fire.

On 25 September 1915 at Thélus-Ecurie in Artois, the regiment held their second line after two hours of fierce fighting against French assaults. The French regiment, also numbered 63, was forced back to the former German first line. This position was heavily contested over the following two days by IR 63 and the French 107th regiment.

From October 1915 to June 1916, the Silesians were stationed along the Somme River between Maricourt and Curlu, where they conducted several night raids against French troops and the Manchesters of the British Army. The indicative size of a raiding party can be illustrated by Stosstrupp III (the third of six formed), which consisted of one warrant officer (Fähnrich), 5 NCOs, 30 men, and 15 pioneers from the 6th Pioneer Battalion. A strong attempt to attack the French lines was made on 14th June at Fargny, but the barbed wire rendered it impossible.

Challenges of 1916

The 1st of July 1916 was the darkest day for the 12th Silesian Division which lost up to 60% of its men. French regiments 37 and 146 attacked IR 63 in the morning. When the 63rd tried to retake Curlu, heavy artillery fire stopped the counterattack at 15.00 hours.

When the regiment returned to the front line at Warlencourt Windmill on 4 August 1916, it received the first steel ‘coal scuttle’ helmets. According to the war diary, Australians attacked with hand grenades four days later and the bloody melee pushed the Germans northwards. IR 63 held trenches north of Martinpuich and the Bayernriegel and Gallwitz Riegel (Gird Trench) north of Flers.

Heavy losses again forced IR 63 into reserve, at Saint Quentin where they were visited on 11 August 1916 by the Emperor Wilhelm II. Afterwards they moved to Monchy le Preux, relieving the 73rd Fusilier Regiment (Hannoverian). (The latter regiment was that of Ernst Jünger, writer of Storm of Steel, who first saw a soldier wearing the Stahlhelm M16 on 23 August 1916, soon after returning from convalescent leave. That same day in Combles, Jünger received his steel helmet.)

The 63rd would have to endure the hell of the Somme until November 1916, when they defended the Feste Soden south of Serre against assaults by the 11th East Lancashire Regiment.

Christmas 1916 was spent in the trenches at Beine-Nauroy, positions they had occupied two years earlier.

The 12th Silesian Division on the Eastern Front: Life at Illuxt

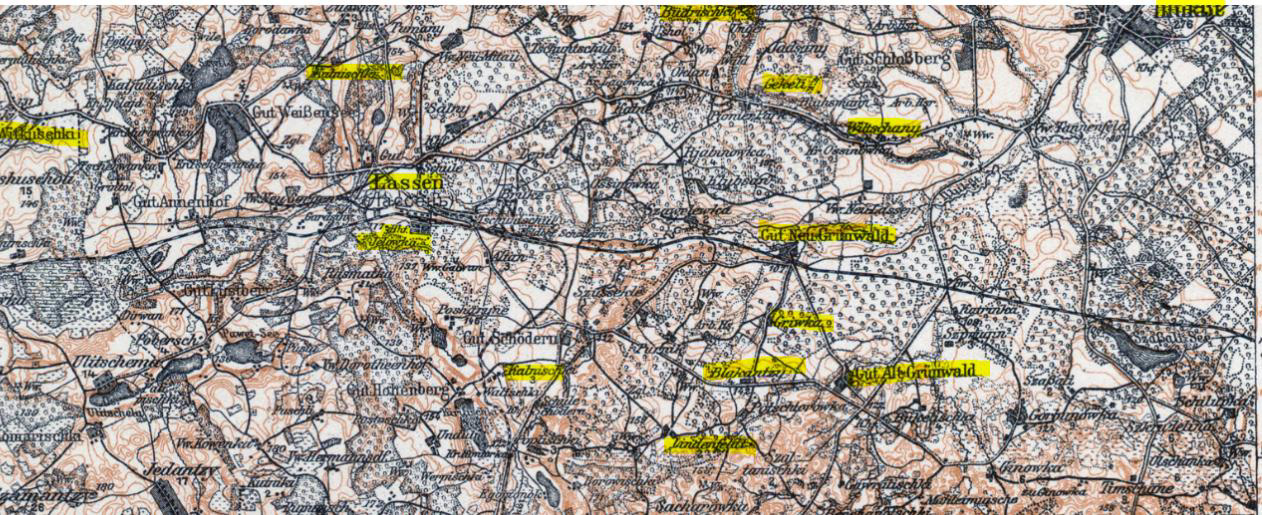

After enduring intense fighting on the Western Front, the 12th Silesian Division was transferred to the Eastern Front. On 3 January 1917, the division entrained at Rethel for Jelowka (today Eglaine in Latvia) where they arrived four days later. IR 63 was assigned a static front at Illuxt, a wooded sector encompassing the old castle of Illuxt and many small villages, including Abeli, Gut Witkuschki, Gekeli, Lassen, Burakischi and Wiltschany.

This section of the line had been captured in October 1915. The German trenches were well-constructed. In advance was a river and six mine craters dating to 1916.

On 11 January 1917, a gas alarm was given, but despite the alert, the front remained quiet. On 26 January, IR 63 was trained in front of General von Hutier, and in February, some soldiers began training with snowshoes.

Between 18 and 22 March 1917, sentries noticed a large board near the Russian trench announcing the revolution in St. Petersburg. Possibly taking advantage of this, the Silesians harassed Russian observers with sniper fire the next day. The Russian response, with artillery and rifle fire, prompted the 7th Company to conduct a raid on 26th March, capturing 26 prisoners.

At 3:30 am on 27 March, the 1st Battalion of IR 63 faced Russian patrol activity after an intense artillery barrage of approximately 1,000 shells. About ten Russians entered a trench known as ‘Donhoff-Schanze’ but were repelled with hand grenades. German losses amounted to only eight wounded.

On 30 March, 300 Russians attempted to attack German positions, but mortar and artillery fire thwarted their efforts. A countermeasure was planned for 5:30 pm on 2nd April. While Russian artillery was suppressed with gas shells, a Sturmtrupp from IR I/63 (1st Battalion) and Machine Gun Company 1, wearing white helmet covers, attacked on the right flank, capturing 89 prisoners (including two officers) from the 550th Russian Infantry Regiment and seizing equipment and two Russian machine guns. These were later deployed in summer 1917 at Zillebeke in Flanders.

Although a Sturmkompagnie from the 12th Infantry Division existed, on 12th April, an order was given to avoid offensive actions against the Russians. However, enemy snipers continued to harass the Silesians, resulting in the loss of Captain Hofrichter of the 3rd Battalion IR 63 and medic Dr. Gensichen.

On 19 April, German artillery opened fire on the Russian lines due to sniper activity while I/63 was relieved by III/23. On 25th April, further Silesians were killed, and the German response was the same as before.

On 1 May 1917, singing and red banners with slogans such as ‘Come to us; we give you freedom and bread!’ were heard from the Russian lines, but nothing resulted.

Ten days later, it was reported that IR 63 snipers had killed several enemy officers. On 16 May, the regiment prepared to move from Illuxt to Szubbat-Rakischki, where they were visited by the divisional commander and Generals von Kirbach and von Berrer.

Final years and tactical evolution

At the end of May 1917, IR 63 returned to France, and from Metz, they marched to Les Vallons, near Jury. Over the course of a week, they trained with the new MG 08/15 and prepared for what would be called the Third Battle of Ypres.

Many Silesians would lose their lives in that brutal fight, and over the remainder of the war, but they would perfect their assault tactics.

In Italy, during the 12th Battle of the Isonzo, they demonstrated their tenacious and expert art of war by capturing the 89th and 90th Italian Regiments with the assistance of the Württemberg Mountain Jaegers, led by First Lieutenant Erwin Rommel, the future Field Marshal of the German Africa Corps.

IR 63 was renamed on November 10th, following its success at Caporetto, becoming Infanterie-Regiment Kaiser Karl von Österreich und König von Ungarn (4. Oberschlesisches) Nr. 63. This renaming marked the pinnacle of recognition for the regiment’s mastery of assault tactics. Among its notable achievements, Leutnant Walther Schnieber was awarded the Pour le Mérite for his leadership in capturing Monte Matajur.

The regiment had been highly praised for its exceptional courage and performance during operations from Caporetto to Ragogna and later to Vidor. On November 3rd, Kaiser Wilhelm II wrote to Austrian Emperor Charles I, commending IR 63’s remarkable service. In honor of this distinction, Charles I was named the regiment's chief, leading to the new name, and a change in their shoulder insignia. The "63" was replaced with a "K" and two crowns, symbolizing their steadfast dedication and sacrifices over three years of war.

Article by Matteo D’Angella