Lily Wedge – A Portsmouth War Widow

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Lily Wedge – A Portsmouth War Widow

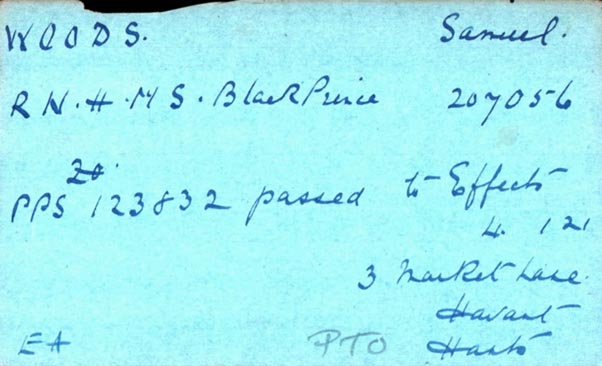

This investigation began during the ‘Big Push’ project, with the discovery of a pension card for a man who served in HMS Black Prince, which was lost with all hands at Jutland.

At Jutland, Black Prince became separated from her sister ships, and, during the night following the main action, had the misfortune to encounter a line of the German Fleet, and had no chance of survival when picked out by searchlights, being then engaged by several battleships at point blank range.

Rather surprisingly, Samuel Woods was found to have survived the war, only to die in 1920 soon after leaving the service, but is not commemorated by the CWGC.

This story attempts to resolve the apparent mystery regarding Samuel Woods, but really revolves around his widow, Lily, a Portsmouth lady, who had already lost her first husband during the war, and had no less than three sons in the Royal Navy, the elder two being twins who served throughout the war.

A plethora of pension cards and ledger entries relate to the various claims made by Lily.

Lily – The Early Years

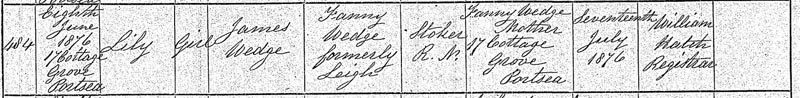

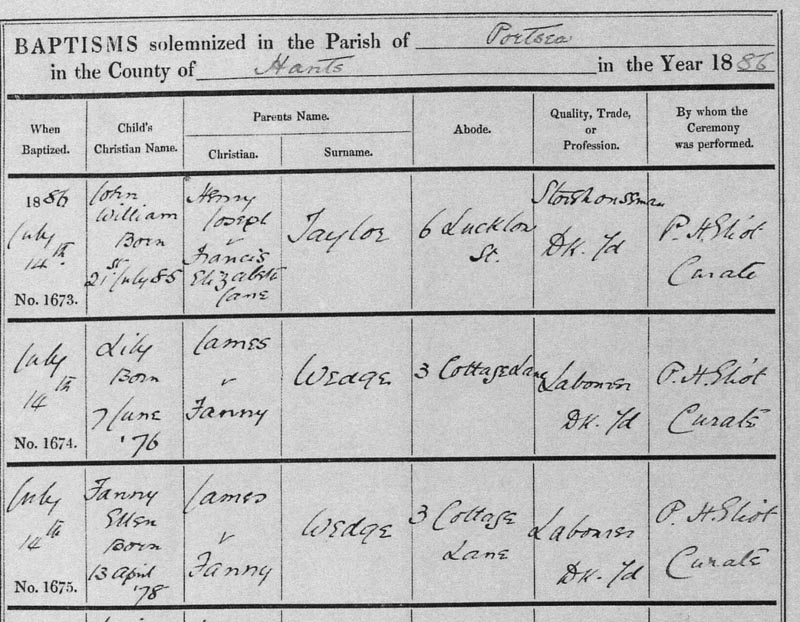

Lily was born as Lily Wedge on 8 June 1876, at 17 Cottage Grove, Portsea, so a true ‘Pompey’ girl.

She was the daughter of James Wedge and Fanny Leigh, who married at St Mary’s, Portsea, on 12 February 1871, James being a Royal Navy stoker, serving in HMS Himalaya. There were several marriages at the church on that day, which might explain why the cleric failed to enter the church name in the register.

The 1871 census for 11 Delhi Street, Portsmouth, lists Fanny as a stoker’s wife, and living with her first daughter, Ada. This document confirmed that James was then serving with the Royal Navy.

James Wedge’s naval record in series ADM 139 records his birth as 17 December 1840 at Landport, tallying with his birth register entry in the first quarter of 1841, in the Portsea Island district. His occupation as a stoker in HMS Himalaya at the time of his marriage is also confirmed.

He was engaged as a stoker for ten years by the Royal Navy on 2 April 1870, but under the name James Wade. He later admitted to being James Wedge, and provided the appropriate birth certificate. He also then claimed previous service under the names James Wedge or Wadge, from 1859 to 1867, which would help explain his absence from the 1861 census.

Details of conduct and assignments during this period were later entered onto his record sheet, but apparently not until 1888, and show his early service was mainly as ward room cook, which would have involved responsibility for feeding the commissioned officers.

His service record, located in series ADM 188, under James Wade, alias Wedge, shows his civilian trade was that of a baker, and that he served a short spell in Portsmouth Gaol, in July 1879, before being discharged to shore on 23 April 1880.

This was a difficult year for the family, the birth of twins Louis Alfred and William Harry being registered in the second quarter of the year, with the death of the former, registered as Lewis Alfred, occurring in the same quarter. Shortly afterwards there were even harder times, as the Portsmouth workhouse register shows that Fanny Wedge was admitted on 6 July 1880, along with her children Ada, Daisy, ‘Lillie’, Fanny and William, and discharged a month later on 6 August.

On 8 August James Wedge committed a burglary at a house in Portsea, and the Winchester Prisoner Register reveals that he was sentenced in December 1880 to four month’s hard labour. Although this would have placed even more strain on household expenses, no records of re-admission of his family to the workhouse were found. The 1881 census for James confirms that he was a prisoner at H.M. P. Winchester, and records him as a fireman by occupation, born in Portsmouth.

This census shows young ‘Lilie’ and her siblings now living with their mother Fanny at 20 Binstead Road, Portsea. Fanny was employed as a charwoman. Her elder brother James was with a naval pensioner and his wife at Balliol Road, Portsmouth, which would have saved him from the workhouse.

1881 was another bad year for the family, Lily losing her sister Daisy, and also her brother William Harry in the third quarter of that year.

James Wedge didn’t stay out of trouble for long, being convicted of larceny on 4 July 1884, having stolen a jacket at the end of May, and he was committed to a further six months imprisonment with hard labour, his previous offence being noted.

The next evidence of James is on 22 October 1886, when a settlement order was issued to return him from London, where he was presumably an unwanted pauper, to Portsea Island.

The 1891 census finally reveals James and Fanny living together, at 81 Havant Road, in the Copnor district of Portsmouth. James is described as an agricultural labourer, and ‘Lilie’ as a 14 years old domestic servant. Just one more child would be added to the family, Florence Kate born 24 November 1892.

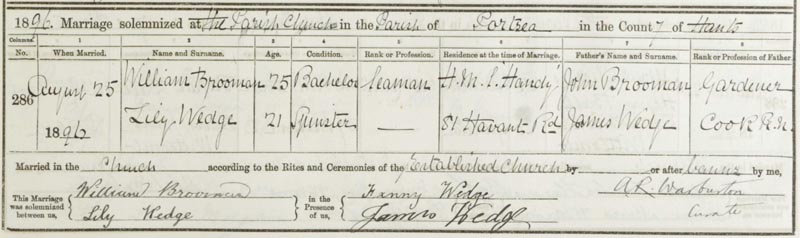

William Brooman

Lily’s first marriage took place in August 1896 at St Mary’s Portsea, the church where her parents had also married. She was still living at 81 Havant Road, and her father James’ occupation was given as Cook, R.N., although that appears to be a reflection of his Royal Navy service some thirty years earlier, rather than his current occupation.

Lily’s husband, William Brooman, was a seaman serving in the torpedo boat destroyer H.M.S. Hardy.

William Brooman, was born on 15 October 1871, and baptised on 10 December 1871 at Holy Trinity Parish Church Hastings. He was the son of John Brooman, a coachman, and Caroline Elizabeth Foster, who had married on Christmas Day in 1870 at Fairlight near Hastings. He joined the Royal Navy on 15 October 1889.

The 1901 census records William and Lily at Camber Coastguard Station in East Sussex, with children William, aged 3 and Lily aged 3 months. William’s service record notes him as a boatman at Camber at that time, and shows that he was awarded his long service and good conduct medal in 1904, after the appropriate fifteen years service.

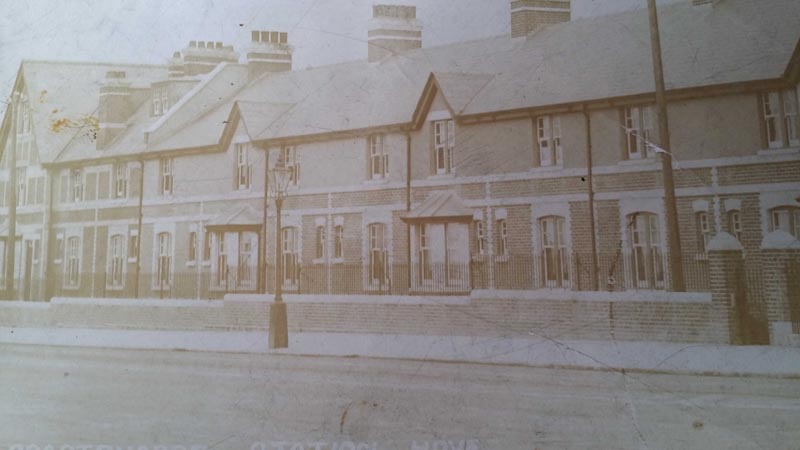

The 1911 census has William as a leading boatman at the Royal Naval Barracks in Edinburgh Road, Portsmouth, while Lily was noted as a coastguard’s wife, residing at No 4 Coastguard Station, Hove, and with four children at school.

Using a combination of the General Register Office birth records, plus pension cards, it would appear that William and Lily had eight children in all, between 1897 and 1912.

Twins, John Albert Victor and William James Charles, were born on 13 June 1897, and baptised together on 1 July at Portsea St. Stephens. Lily was still living at Havant Road, but was by then at number 65.

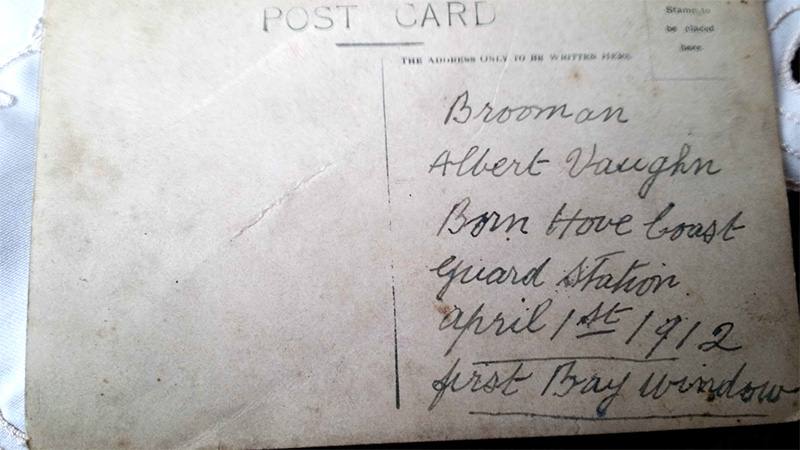

The births of their next three children were registered in Rye, Florence Lily born 24 December 1900, George Edward on 4 July 1902, and Robert Herbert on 31 March 1904. Daughter Ivy Dorothy was born 7 May 1906 and registered at Romney Marsh, while Phyllis Fanny’s birth was registered second quarter 1908 in Dover, with her death registered there in the fourth quarter of that same year. The last child was Albert Vaughan, born 1 April 1912, with his birth registered in the Steyning district of Sussex. Note that births are sometimes registered in a different district to where the birth occurs.

The 1911 census shows the twins as pupils of the Royal Naval School at Greenwich, but recorded as Albert and William. This establishment was for the sons of Royal Navy officers and seamen, and of Royal Marines and Coastguards, they being eligible for entry about the age of 11, provided they were fit for sea duty and possessed basic reading and arithmetic skills.

William’s coastguard duties came to an end in July 1914, when, with the Great War pending, he was posted to HMS Mars. This ship was used to guard the Humber estuary at the beginning of the war, but was decommissioned in February 1915 after a spell on the Dover Patrol.

After a spell ashore, William was assigned to HMS India, on 19 April 1915.

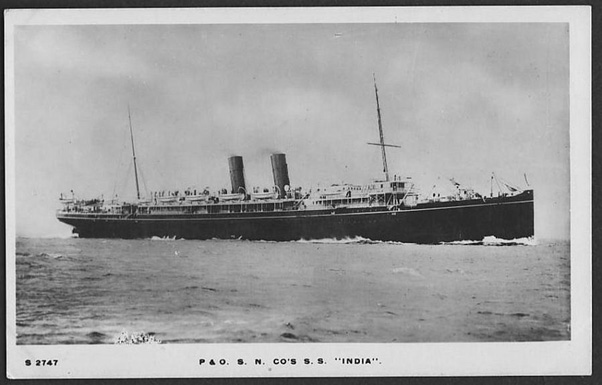

India was employed during the war as an armed merchant cruiser, intercepting and inspecting neutral shipping, but was sunk by submarine U-22 on 8 August 1915 in the Norwegian Vest Fjord, off the island of Helligvaer, near Bodo, while on North Sea Patrol.

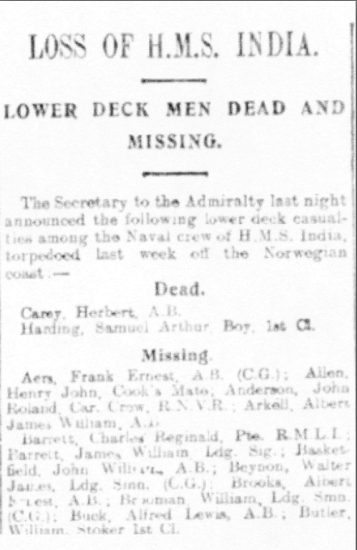

The loss of the ship was reported in the Portsmouth Evening News on 13 August followed by a list of the 22 officers and 119 men who were saved, and later interned in neutral Norway. Sadly William was not amongst the list of survivors.

It was probably at least a year before Lily was informed that William was considered officially to be dead. She and the family placed ’in memoriam’ notices in the Portsmouth Evening News of 9 December 1916.

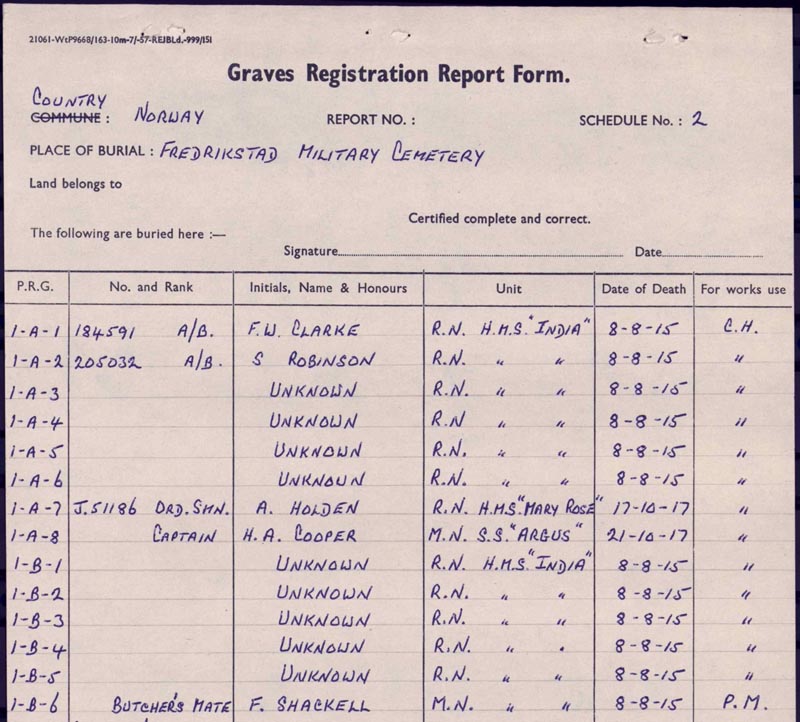

It is possible that William may lie in Fredrikstad Military Cemetery, where another handful of identified ‘India’ men lie buried, along with a number of unknown sailors known to be from this same ship.

William is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, although most of the other unidentified casualties are commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

The Royal Navy Medal Roll shows that Leading Seaman William Brooman’s 1914-5 Star, and subsequently the British War and Victory Medals, were disposed of to his widow. The entry on the roll after William Brooman’s name is that of his son William James Charles (see later for more details of his service).

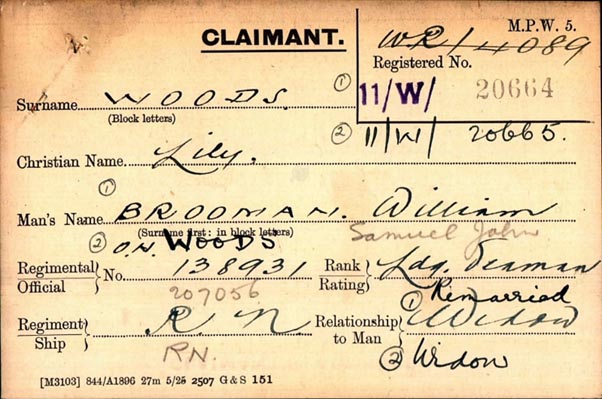

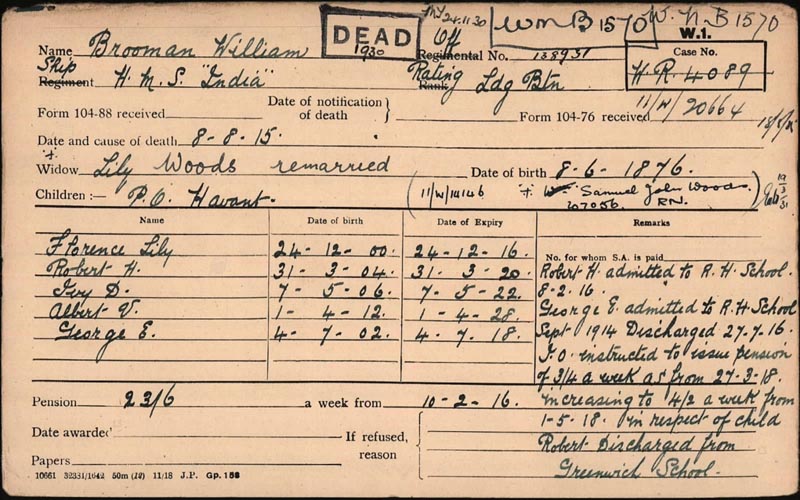

Both the CWGC register for William and Pension Card provide evidence that his widow Lily re-married, taking the new surname of Woods. Note that he is recorded both as a Leading Seaman and a Leading Boatman (Coast Guard).

This card shows, for each child, their date of birth and the pension expiry date, at age sixteen, after which they would no longer be considered a dependent for pension considerations. The card has clearly been subsequently updated to record Lily’s second marriage.

At this time Lily’s pension would have ceased, with a gratuity equivalent to a year’s pension paid as a lump sum to her new husband. The Treasury introduced this ‘dowry’ offer as an opportunity to avoid supporting a widow for the rest of her life. It was also considered that it was in the country’s interest that a widow should remarry, either to have more children to replenish the depleted population, or to provide a father figure to help raise the ones she already might have, in a respectable manner.

The Royal Navy tradition within the family is evident, with Robert Henry and George Edward Brooman attending the Royal Hospital School at Greenwich. George Edward later joined the Royal Navy in 1921.

The twins John and William are not listed on the card, being no longer dependents. Both had attended the Greenwich school, as noted previously in the 1911 census record, and subsequently served as boys in the Royal Navy from 1912, before entering into 12 year service engagements on the same day in 1915.

This must have been a very worrying time for their mother Lily, who had not only lost her husband in 1915, but had two sons at sea.

John’s first wartime service, in 1915, was in the dreadnought battleship HMS Iron Duke, then the flagship of the British Grand Fleet.

Following a period of shore service he was posted to the cruiser HMS Attentive, followed by a further spell ashore. His next vessel was the ‘Q’ ship HMS Cullist. He was very fortunate to receive a further shore posting just weeks before ‘Cullist’ was sunk by U-97, with the loss of over half her complement.

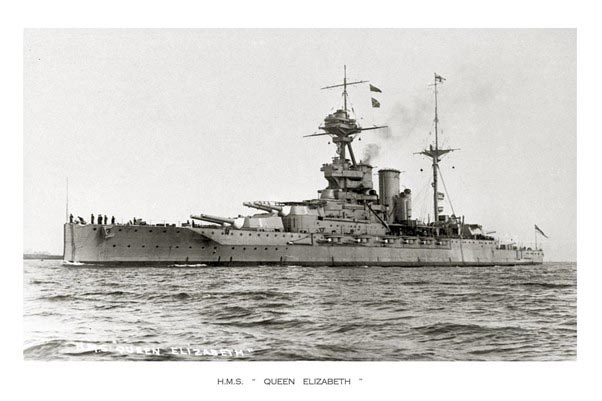

William served throughout the war in the super-dreadnought battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, which missed the battle of Jutland while in dry dock at Scapa Flow, and afterwards took over the role of flagship of the Grand Fleet in 1917.

Both twins not only served throughout the war, but continued afterwards, each being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal, after fifteen year’s service, respectively to A.B. John Albert Victor Brooman, HMS Nelson on 8 August 1930, and to Leading Signaller William James Charles Brooman, HMS Vivacious on 23 August 1930.

It could be said that the Brooman family had well and truly done their bit in both the war effort and in later providing the Royal Navy with manpower.

Not content with Great War service, John Albert Victor Brooman continued his naval career into WW2, being taken prisoner in September 1941, while serving with the depot ship HMS Martial, which was based in Alexandria. Online POW records show he was held in Stalag VIII B Teschen, in the present day Czech Republic. He was probably captured by the Italians, and later handed over to German control, before eventual repatriation, which took place, according to his naval record, in May 1945.

Samuel Woods

The marriage of Lily Brooman, to her second husband Samuel Woods, was recorded in the Havant district in the fourth quarter of 1919, probably in the local Register Office, as the entry cannot be found in available parish records.

Although Samuel is occasionally referred to as Samuel John Woods on various pension cards, his birth was actually registered as Samuel James Woods in the Westbourne district of Sussex in the second quarter of June 1895, his mother’s maiden name being Powell.

The 1891 census for the hamlet of Southbourne, in the parish of Westbourne, shows six year old Samuel as a scholar born in Southbourne, and living with his parents James, a market gardener, and Elizabeth.

He enlisted as a boy sailor in 1899, with an evident adjustment to his date of birth, to ensure acceptance, as is commonly seen in such documents.

His father was at that time the inn keeper of the ‘Old House at Home’ in Southbourne, as well as following his trade as a gardener. Samuel was an able seaman in 1911, serving in the battleship HMS Exmouth at Malta.

War Service

Samuel’s service record shows he certainly served in HMS Black Prince, but this was pre-war, between May 1912 and 20 April 1914, so he was definitely not with this ship at Jutland in 1916.

His wartime service commenced with a transfer to the Hawke Battalion of the Royal Naval Division, (R.N.D.) formed in September 1914 to fight on land alongside the Army, and consisting of men from the Royal Navy, Royal Naval Reserve, Royal Fleet Reserve, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, Royal Marines, and the Army.

Hawke, and other R.N.D. battalions, along with part of the Belgian Army, was besieged at Antwerp by the German army, at the beginning of the war, and trapped in the fortified city. When the remaining garrison eventually surrendered on 9 October 1914 some troops, including Samuel, managed to escape to the Netherlands, but were interned, in accordance with international law, for the duration of the war.

Brief details of his wartime experiences are recorded in his summarised Royal Naval Division record, held at the National Archives. A much more complete service history for Samuel will almost certainly be available at the Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovilton.

Unfortunately the available war diary for Hawke Battalion, in series WO 95 3114/2, only commences after control of the Royal Naval Division had passed to the army, at which time it was renamed the 63rd (Royal Naval Division). The first diary entry is for May 1916, in France, with the arrival of the 1st Battalion in Marseilles, so there is of course no mention of the action at Antwerp or the internment in Holland. The diary continues until 31 May 1919, but again there are no entries relating to internees, or whether any of them re-joined the battalion.

Internment in Holland

The men were initially housed in a military barracks, but a new internment camp, for some fifteen hundred men of the Royal Naval Division, from Collingwood, Hawke and Benbow battalions, was set up in early 1915 in the city of Groningen, and being composed of wooden huts was known to the inmates as HMS Timbertown, and to the local inhabitants as the Engelse Kamp.

A series of excellent articles regarding this camp was written in 2002 by a local amateur historian, Menno Wielinga, later translated into English by Guido Blokland, and accessible on the wereldoolog1418.nl website, and provided the source of the bulk of the following information regarding the camp and internees.

To relieve boredom there were craft facilities, particularly for woodworking, and sports were encouraged, with competition extending to football matches against civilian teams. A notable result in November 1916 was a 1-1 draw, by the combined Brigade team, against the famous Ajax of Amsterdam. Dramatic and operatic societies were formed, along with a cabaret company, the ‘Timbertown Follies’, and even a knitting club was established.

There were several escape attempts, including some ‘home runs’, but the implementation of local passes into Groningen by 1915 alleviated the problem. By 1916 the British Government introduced a diplomatic policy of returning escaped internees. Later on compassionate home leave was allowed, with a strict understanding that any default to return would result in cancellation of the scheme. In January 1917, no less than 350 internees were in the United Kingdom because of claimed ill health or next of kin problems, the usual leave period being one month.

A generous group leave scheme was sanctioned in 1917, replacing ‘compassionate’ leave, but restricted to men with a record of good behaviour, and with a stipulation that they were not allowed to undertake war related work while away. Leave was not without danger, with three men losing their lives to submarine attack, and ten being taken prisoner by the Germans.

A number of friendships were established with local families, and several men married Dutch girls. Men were allowed to work locally, often on a voluntary basis, and provided they did not deprive locals of jobs.

It would appear that the food was poor, and only got worse as the war went on, partly as a result of submarine blockades, to the extent that in April 1918 the men refused to take part in the daily compulsory exercise, claiming weakness. Another general cause for complaint was insufficient heating in the winter months. A total of eight men died while interned at Groningen.

Some 300 men did not require repatriation after the war as they were already in the UK when the armistice was declared, and the camp officially closed on 1 January 1919.

Post War

Samuel was repatriated on 19 November 1918, and transferred to the Royal Naval Depot on 23 January 1919, he left the service soon afterwards on 26 February 1919.

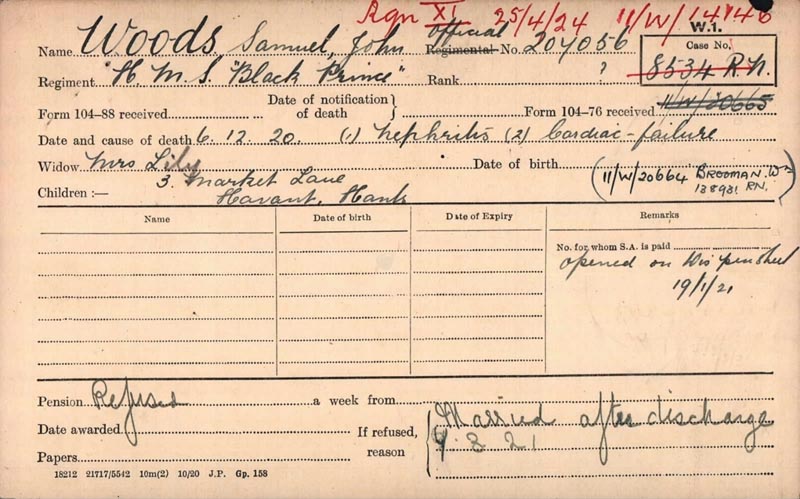

He then married Lily Brooman, in late 1919, but very sadly died in the Queen Alexandra hospital in Portsmouth in the following year, on 6 December 1920, of nephritis and cardiac failure, his death being registered as Samuel J. Woods, in the Portsmouth district, aged just 36.

The Royal Navy Medal roll shows that Able Seaman Samuel Woods was awarded the 1914 Star, claiming clasps and roses to show he served under enemy fire in the qualifying period. This is a relatively unusual award to a Royal Navy man, and was issued to him before his death. The roll shows that his British War Medal and Victory Medal were disposed of to his widow in 1922.

Lily was still living at 3 Market Place, Havant, when the 1921 census was taken, along with her children George Edward, Robert Herbert and Albert Vaughan Brooman.

The question remains as to why Samuel Woods’ pension cards relate to his service in a ship, H.M.S. Black Prince, in which he served before the war commenced, and which was a total loss at Jutland, and not to his service with Hawke Battalion of the Royal Navy Division. The final pension card regarding Lily’s claim against the death of Samuel Woods is of considerable interest.

Not only does it give the date and cause of death of Samuel, but it also shows that her claim was rejected the following year on the basis that she had married Samuel after his discharge.

This appears to have been a very harsh decision, as the marriage took place just months after his discharge, and his death was more than likely brought on by the conditions experienced during his internment, so surely somebody had to deserve a pension on his behalf, and the most eligible would have been Lily, his widow. However rules had to be followed, so Lily had to be content with being entitled to his medals, but not a pension.

It is remotely possible that Lily, no longer in receipt of her small pension following the loss of her first husband in HMS India, and having now lost her second husband, and with a family to support, felt that a pension might be forthcoming if a claim was put in that might mislead the authorities to assume her second husband had been lost in HMS Black Prince, and not post war. It is however much more likely that this was not the case, and that any references to ‘Black Prince’ were merely just typical examples of pension department inefficiencies and clerical blunders.

It seems that Lily Woods did not marry for a third time, the 1939 Register found her residing in Scunthorpe with her married son, Albert Vaughan Brooman, by then a steelworks driller. Albert’s date of birth was as expected, but that of Lily was mistakenly recorded as 7 June 1878, rather than 8 June 1876.

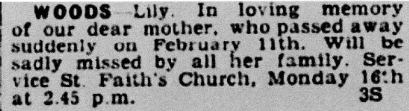

She evidently returned to her old haunts, as her death is almost certainly that registered in the Gosport district, aged 76, in the first quarter of 1953.

Summary

What was originally intended to be a straightforward tale of a sailor lost at Jutland in ‘Black Prince’ turned into the remarkable story of a Portsmouth girl, daughter of a Royal Navy seaman, whose family hit hard times in the 1880’s, who lost her sailor husband during the Great War, then married a recently demobbed sailor, fresh from the war, only to lose him soon afterwards, and had no less than three sons who served in the Royal Navy, two for much of the Great War, and with one of those becoming a POW in WW2.

There is a real sadness in that not only did she lose two husbands within a short period, but was very harshly treated, and although receiving two sets of war medals, the rules were strictly applied to deny her a pension on behalf of her second husband, having almost certainly lost the lifelong pension awarded for the loss of her first husband, to a single payment of one year’s entitlement when she re-married.

As a final note, Samuel is not commemorated by the CWGC, although his death appears to have been very likely related to his internment.

The book ‘British Widows of the First World War, the Forgotten Legion’ by Andrea Hetherington proved more than useful in this research, and is thoroughly recommended to anyone with an interest in social history.

Article contributed by Dr. Alan Hawkins