After Amiens – 38th (Welsh) Division

- Home

- World War I Articles

- After Amiens – 38th (Welsh) Division

It happened in the barber’s where my mother had taken me when I was a young child.

‘Mummy, why is that man making funny noises?’

The wheezing, rattling and muted bubbling sound stopped briefly as he turned to look at me, expressionless, then nodded towards my mother and turned away.

My mother gave a very, very sharp tug on my coat sleeve. ‘Shhh! You’re being rude. I’ll tell you when we get outside.’

And so she explained. The man had been gassed during the First World War. ‘You know what a war is, don’t you’ said my mother. Actually, I did, my father having just returned from one. My mother went on: ‘He was in the local Regiment, the Welsh Regiment, I think. Do you know what a Regiment is?’ Actually, I did, my father having been in one and having told me what it meant.’

I don’t think I saw that poor suffering man again.

But I suppose it might have been at that moment in the barber’s – or perhaps more precisely just afterwards when my mother did her best to satisfy my childish curiosity – that my interest in the First World War began.

And, every now and then, even after I had left Wales, my interest focused on the Welsh soldiers in that war. How had that man become a soldier? Why had he joined the Welsh Regiment? (Wasn’t it the ‘Welch’ Regiment anyway? That’s what the soldiers who lived in the nearby Maindy Barracks had on their cap and shoulder badges.)

I came to wonder, in the course of time and learning, why the 38th (Welsh) Division in the First World War, that so many men in the Welsh Regiment belonged to (in fact, including the Pioneer Battalion, there were seven Welsh Regiment battalions in this Division at its formation), did not seem to have been ‘famous’ or regarded as having a great ‘fighting reputation’ despite its impressive record in battle between 1916 to 1918. And its record in battle was, indeed, impressive.

In 1916 in the Battle of the Somme the Division captured the largest wooded area in the battlefield, Mametz Wood, in five days, whereas it took other units months to capture the much smaller High and Delville Woods. In 1917 on the opening day of the Third battle of Ypres, while others floundered, the Division rapidly advanced three kilometres and achieved all its objectives. In 1918 at the start of the British counter-attack and final advance the Division advanced 15 miles in 15 days setting the pace that the British army maintained until the Armistice.

Perhaps the reason for the paucity of official praise for the Division’s achievements (until 1919) is its association with David Lloyd George, the Welsh Liberal politician and Prime Minister from December 1916. It is safe assumption that few Generals in the British Army were Liberals. It is also a safe assumption that many, perhaps most, regarded him as an untrustworthy parvenu Welsh ‘outsider’, dangerously ignorant of military matters. It is true that the 38th (Welsh) Division did not get off to an easy start.

The creation of 38th (Welsh) Division

The creation of the Division began with a speech made by David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, on 19 September 1914 at a meeting of London Welshmen at the Queen’s Hall in which he had appealed for the formation of ‘a Welsh army in the field’. Subsequently, in order to give this idea substance, the Welsh National Executive Committee was formed in Cardiff on 29 September to organise the recruitment of ‘a Welsh Army Corps’ of two or more divisions.

Every effort was made by the WNEC to create a totally Welsh formation. The use of the Welsh language within units was encouraged and many of its recruiting posters and leaflets were printed in both English and Welsh. It was planned to give recruits distinctive uniforms made of ‘brethyn llwyd’ (trans. ‘grey cloth’) woven in Wales. These uniforms proved immediately problematic. 13 Welsh mills were contracted to produce the brethyn llwyd, each coming up with their own shade of ‘grey’ ranging from blue grey to grey to khaki to brown. In fact, the uniforms produced for the 11th Battalion Welsh Regiment by outfitters Messrs' Jotham of Cardiff were so brown that it led to the unit becoming nicknamed ‘The Chocolate Soldiers’. Supply problems were experienced from the outset and fewer than 9,000 brethyn llwyd uniforms were actually produced for the 50,000 Welshmen who had volunteered by the end of 1915. Finally, standard khaki uniforms were supplied to the Division and brethyn llwyd uniforms never reached the battlefield. (Source for this paragraph: National Museum of Wales)

Although the initial response to the recruiting campaign was enthusiastic, in the event the ‘Welsh Army Corps’ was confined to a single division. Originally numbered 43rd in Kitchener’s New Army, it was renumbered 38th in April 1915. By the Armistice 280,000 Welshmen had fought in the First World War – 28% of the male population, the largest proportion of the male population in any part of the UK.

After a period of training that was to prove largely outdated and irrelevant (eg there was no practice live-firing of machine guns) and after a struggle to find sufficient officers with experience, the Division began to move to the Front in Artois on 1 December 1915 and then moved south to prepare for the forthcoming Battle of the Somme.

The Division’s actions in 1916 and 1917 – in summary:

On 5 July 1916, the Division received orders to attack Mametz Wood two days later.

The wood was captured on 12 July. There, ‘... the Welsh division, inexperienced (it was composed of entirely volunteer Battalions) and inadequately trained, pushed the cream of Germany’s professional army back about one mile in most difficult conditions, an achievement which should rank with that of any division on the Somme …’ Colin Hughes: Mametz – Lloyd George’s’ Welsh Army’ at the Battle of the Somme, Gliddon Books 1990.

The Division’s casualties for the period 7-12 July totalled nearly 4000 including 600 killed and about 600 missing. The worst Battalion casualties were those of the 16th Welsh (Cardiff City) Battalion which had fought in the 7 July battle and then in the Wood itself on 11 July. It suffered more than 350 casualties – almost half its fighting strength. ‘On the Somme the Cardiff City Battalion died’ – Private W B Joshua, 16th Welsh.

It was to be just over a year before the Division was engaged in another major battle – the Third Battle of Ypres.

The Division’s attack on Pilkem Ridge on 31 July 1917 was a success and Field Marshal Haig was to write in 1919 that this action was an occasion which ‘reached the highest level of soldierly achievement’. Indeed, as he pointed out, ‘the 38th (Welsh) Division met and broke to pieces a German Guard Division.’

The Division later fought around St Julian and Langemark and was then moved to Armentieres just over the border in France.

38th (Welsh) Division in 1918 – an amazing story:

The Division’s artillery had played an important part in slowing down, then halting, the German attack in the Battle of the Lys in April 1918. Armentieres was captured by the Germans but they did not manage to advance much further.

Even before this, the Division’s infantry had been moved south to counter the German offensive opposite Amiens which had begun on 21 March. By 2 April the Division was five miles north-west of Albert. Following the German capture of Albert the Division took over a defensive line to the west of the town. By 2 May the

Division was holding a line from Aveluy Wood to Mesnil and fighting to win higher ground. After being withdrawn for rest on 20 May, the Division returned to the line from Aveluy Wood to Hamel and remained there until 19 July when it was withdrawn for rest and training. On 5 August the Division returned to the area of Aveluy Wood.

On 8 August the British Army returned to the offensive.

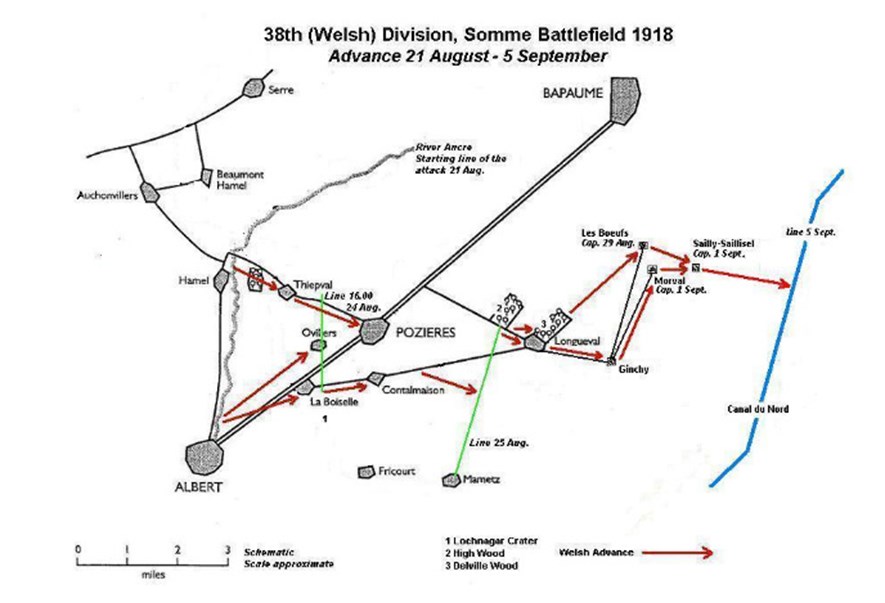

The 38th (Welsh) Division was called upon to drive the Germans back from Thiepval Ridge and advance to Pozieres. The action began on the night of 21/22 August when 14th Welsh penetrated Thiepval Wood. The following night, 22/23 August, 15th Welsh crossed the River Ancre, wading through water up to their chests and under fire. That same night 113th Brigade advanced from Albert (now recaptured) and 13th RWF captured Usna Ridge. On the night of 23/24 August more units of the Division advanced and the main attack began. 114th Brigade captured Thiepval Ridge, 113th Brigade captured La Boisselle and 115th Brigade captured Ovillers. By 16.00 the Division had advanced to a north-south line east of Ovillers having captured 634 prisoners and 143 machine guns. By the evening of 24 August 113th Brigade had pushed on to Contalmaison and the other two Brigades had taken Pozieres.

On 25 August the entire Division advanced to the line of High Wood-Mametz Wood. Mametz Wood was captured by 113th Brigade. Though High Wood remained uncaptured the advance continued on 26 August to Longueval. L/Cpl H Weale (14th RWF)* won the VC at Bazentin-le-Grand.

On 29 August 113th Brigade captured Ginchy and 13th Welsh of 114th Brigade captured Delville Wood (which had taken six weeks to capture in 1916). In the evening 10th SWB of 115th Brigade captured Les Boeufs but the advance was then held up at Morval – a strong German position. After prolonged bombardment 114th Brigade captured Morval on 1 September and 113th, Sailly Sallisel.

The advance continued to the Canal du Nord where the bridges over it had been blown. However, on 4 September 13th Welsh of 114th Brigade got across the Canal via the debris of a fallen bridge. A similar crossing was made by 14th and 15th Welsh of the same Brigade.

On 5 September the Division was withdrawn for six days’ badly needed rest.

Since 21 August the Division had advanced 15 miles, fighting all the way. It was an astonishing achievement. But the cost had been high: 3,614 men had been killed and wounded.

In 1919 the usually inarticulate Field Marshal Haig was unusually inspired to write of the beginning of this advance (against Pozieres, 21-24 August) as being ‘a most brilliant operation alike in conception and execution which, with the days of heavy but successful fighting that followed it, was of very material assistance to our general advance.’

(Much more recently, at least one major historian, Gary Sheffield, has given 38th (Welsh) Division its due: ‘…. judged by the results of their attacks during the Hundred Days the 38th (Welsh) Division was in a select band of elite divisions’ akin to the Australian, Canadian and a limited number of other British formations. (‘Finest Hour? British forces on the Western Front in 1918: An overview’ in Ekins, Ashley, ed. (2010). ‘1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History). Titirangi, Auckland: Exisle Publishing Limited.)

In September the Division fought on the Hindenburg Line and in October at Cambrai. Its last major engagements in the war took place 17-22 October at the Battle of the Selle and on 4 November at the Battle of the Sambre.

At the Armistice the leading Brigade of the Division was at Wattignies, 9 km south of the French city of Maubeuge and 13 km east of the Sambre.

The 38th (Welsh) Division lost throughout the war 29,380 killed, wounded and missing (‘History of the 38th (Welsh) Division’; Ed. Lieut. Colonel J E Munby, CMG, DSO; Pub. Hugh Rees Ltd., 1920).

*Henry Weale VC

The VC citation (London Gazette, 15 November 1918) for Henry Weale, 14th Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers (2 October 1897 – 13 January 1959):

‘For most conspicuous bravery and initiative in attack. (26 August 1918 at Bazentin-le-Grand, France)The the advance of the adjacent battalion having been held up by enemy machine-guns, L./Cpl. Weale was ordered to deal with hostile posts. When his Lewis gun failed him, on his own initiative he rushed the nearest post and killed the crew, then went for the others, the crews of which fled on his approach, this gallant N.C.O. pursuing them.

His very dashing deed cleared the way for the advance, inspired his comrades and resulted in the capture of all the machine-guns.’

He later achieved the rank of sergeant.

The TA centre in Queensferry, North Wales is now named the Henry Weale VC TA Centre. He was born in Shotton, Flintshire and is buried at Rhyl. In 2010 a garden was opened in Shotton in his memory. His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum, Caernarfon Castle, Gwynedd, Wales.

38th (Welsh) Division at its formation

|

Brigade |

Battalion No. |

Battalion Name |

Source of Recruits |

|

113th |

13th RWF |

1st North Wales |

Rhyl & surroundings |

|

14th RWF |

Carnarvon & Anglesey |

Llandudno & surroundings |

|

|

15th RWF |

London Welsh |

Welshmen in London |

|

|

16th RWF |

2nd North Wales |

‘Overspill’ from 13th RWF |

|

|

114th |

10th Welsh |

1st Rhondda |

Rhondda Valleys |

|

13th Welsh |

2nd Rhondda |

Rhondda Valleys |

|

|

14th Welsh |

Swansea |

Swansea & district |

|

|

15th Welsh |

Carmarthenshire |

Carmarthen & parts of Glamorganshire |

|

|

115th |

16th Welsh |

Cardiff City |

Cardiff & district |

|

17th Welsh* |

Glamorgan |

Men below min. height in Glamorgan |

|

|

10th SWB |

1st Gwent |

Coalfield & ironworks of Monmouthshire |

|

|

11th SWB |

2nd Gwent |

Monmouthshire coalfield and Brecon |

Divisional Pioneers – 19th Welsh (originally recruited in Glamorganshire)

*Replaced by 17th RWF at the beginning of 1915

Officers Commanding

113th Brigade: Brigadier General L A E Price-Davies

114th Brigade: Brigadier General T O Marden

115th Brigade: Brigadier General H Evans

Officer Commanding 38th (Welsh) Division:

Major General Ivor Philipps

Major General H E Watts (from 9 to 12 July 1916)

Army Reorganisation in 1918

Because of the huge number of casualties incurred in the 3rd Battle of Ypres and because of developments in military technology, in 1918 the number of Battalions per Brigade was reduced from 4 to 3. This reduced the number of infantrymen per Division to 9,000. The Battalion of Pioneers remained but there was an addition of a Machine Gun Battalion. A Division now numbed 16,000 men in total rather than 19,000+. However, the firepower of each Division, in terms of machine guns, was massively increased. In April 1915 each Division had 52 Vickers machine guns (4 per Battalion including the Pioneer Battalion). By October 1918 each Division had 400 machine guns: 64 Vickers plus 336 Lewis (64 Vickers for the Machine Gun Battalion, 36 Lewis guns for each of the nine Battalions and 12 Lewis guns for the Pioneer Battalion). Each Division now also had 36 Light Trench Mortars (12 in each Battery, 1 Battery per Brigade).

38th (Welsh) Division in 1918

|

Brigade |

Battalion No. |

|

113th 1 |

13th RWF |

|

14th RWF |

|

|

16th RWF |

|

|

|

113th Light Trench Mortar Battery |

|

114th 2 |

13th Welsh |

|

14th Welsh |

|

|

15th Welsh |

|

|

114th Light Trench Mortar Battery |

|

|

115th 3 |

2nd RWF |

|

17th RWF |

|

|

10th SWB |

|

|

115th Light Trench Mortar Battery |

38th Machine Gun Battalion

Divisional Pioneers – 19th Welsh

1 15th RWF disbanded Feb. 1918

2 10th Welsh disbanded Feb. 1918

3 16th Welsh disbanded Feb. 1918

11th SWB disbanded Feb.1918

By this time the original 1914/1915 Battalion names were no longer accurate in terms of the origins of their members.

Officers Commanding at the beginning of the final offensive

113th Brigade: Brigadier General H E ap Rhys Pryce

114th Brigade: Brigadier General T Rose Price

115th Brigade: Brigadier General W B Hulke

Officers Commanding 38th (Welsh) Division

From July 1916: Major General C G Blackader

From May 1918: Major General T A Cubitt

At the end of the war 38th Welsh Division was in V Corps, Third Army.

RWF = Royal Welch Fusiliers (The archaic spelling ‘Welch’ was used unofficially by the Regiment and officially used after 1920.)

Welsh = Welsh Regiment (Renamed as ‘Welch’ in 1920)

SWB = South Wales Borderers (In 1969 the Welch Regiment and the South Wales Borderers were amalgamated to form the Royal Regiment of Wales. In 2006 the Royal Welch Fusiliers joined the Royal Regiment of Wales to form the Royal Welsh Regiment.

The War Memorial in Whitchurch, Cardiff, my childhood town.

Welsh National War Memorial, Cathays Park, Cardiff

Even on the finest most carefully planned memorials there can be mistakes. On the outer frieze of this one the inscription reads:

I FEIBION CYMRU A RODDES EU BYWYD DROS EI GWLAD YN RHYFEL MCMXIV - MCMXVIII

(To the sons of Wales who gave their lives for their country in the War 1914 - 1918)

I am told that the ‘EI’ between ‘DROS’ and ‘GWLAD’ should be spelled ‘EU’.

Peter Crook

August 2018