Aftermath: Ireland

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Aftermath: Ireland

Amongst those commemorated on Lewes War Memorial is Lance-Corporal Sidney Wright 1/6th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, aged 22.

One of three brothers lost during the Great War, he was serving in Ireland when he accidentally drowned just outside Wicklow whilst bathing at Travilahawk Strand, between the military camp near the harbour entrance and the Black Castle.

According to the local newspaper,

'he went for a swim about 4.30 in the afternoon. He was not a strong swimmer, and after some time in the water he returned to shore. A comrade, who was nearby at the time, surmising that he was coming out, returned to the camp to dress, and meanwhile Lce-Cpl Wright apparently returned to the water. About 5 o’clock he was missed by Lce-Cpl Burtenshaw, who immediately proceeded in search of him. He was horrified to find the man’s clothing but no trace of his comrade.

A vigorous search was instituted, and a boat in the vicinity which is used by the officers of the regiment was procured. CSM Parks immediately undressed and plunged in, and with the assistance of Pte Henry knight, who dived and brought the body to the surface, and Sgt Truscott and Staff Sgt Punchard, quickly got the poor fellow to the shore. Artificial respiration was applied but it was realised that… the unfortunate man was beyond all human aid…

The fatality cast a gloom over the entire camp, as Lce-Cpl Wright was very popular amongst his comrades, and the greatest sympathy felt by the soldiers at the camp and the townspeople generally with the widow and child… the deceased had only been married some fourteen months. His home was at Lewes, Sussex.'

Lance-Corporal Wright’s body was brought back to Lewes and given a military funeral at Lewes Cemetery, where his gravestone is still maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Sidney Wright was not the only casualty suffered by the 1/6th (Cyclist Battalion) Royal Sussex Regiment whilst stationed in Ireland. Four other men drowned whilst travelling home on leave on 10th October 1918, on board RMS Leinster, when it was torpedoed and sunk by UB-123 an hour out of Dun Laoghaire, with the loss of over 500 lives, mainly military personnel.

Two other Lewes men also died on active service in Ireland, killed during the Irish War of Independence which almost immediately followed the end of the First World War. 2nd Lieutenant Geoffrey Turner Hotblack, 1st Essex Regiment, on 22nd March 1921 and Gunner Bernard Francis, 8th Royal Marine Artillery, on 14th May 1921. Both men were buried in St John-sub-Castro churchyard. Neither man is commemorated on Lewes War Memorial.

The Irish struggle for home rule and subsequently independence can be traced back to the Act of Union of 1800 when the Irish Parliament, from which Catholics were barred, voted to dissolve itself. Daniel O’Connell’s successful campaign for Catholic Emancipation, passed by Act of Parliament in 1829 and the support he received for his public agitation for repeal of the Act of Union, culminating in his arrest and imprisonment for conspiracy in 1843 (a verdict swiftly quashed by the House of Lords), marked the beginnings of a monumental struggle. Two home Rule Bills were passed by Gladstone’s governments in the 1880s and 1890s only to be thrown out by the House of Lords.

However, in 1912 the Liberal Government, dependent for its survival on the votes of Irish representatives, introduced a third Home Rule Bill providing limited self-government to Ireland. Its introduction led to immediate opposition to Home Rule in Ulster and the signing of the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant by almost half a million people by September 1912. This was followed by the establishment of the Ulster Volunteer Force, a Protestant militia of over 100,000 by the end of 1912 and a rival Irish Volunteers to defend Home Rule.

As both sides armed themselves for the conflict to come, the Irish Home Rule Bill was eventually passed as the Government of Ireland Act in September 1914, following an undertaking that Ulster would be excluded indefinitely from its provisions. At the same time a Suspensory Act received the royal assent, immediately suspending the new act for the duration of the Great War, which had broken out on 4th August.

By the spring of 1916 frustrations at the lack of progress towards Home Rule amongst the more radical wing of Irish Volunteers led to the Easter Uprising in Dublin. Its brutal aftermath turned moderate nationalists against the British Army and in the December 1918 General Election of 105 Irish seats, 73 were won by Sinn Fein and 26 by Unionists. The old Irish Parliamentary Party lost 67 seats and was reduced to just 6 MPs. Sinn Fein MPs refused to take their seats at Westminster and instead established themselves as an Irish Assembly (Dail) in Dublin. In January 1919 at a convention in Dublin coinciding with the Sinn Fein conference, the Irish Volunteers were reorganised as the Irish Republican Army with Eamon de Valera, the president of Sinn Fein, at its head. From now on the goal was a total break from Britain and the establishment of a republic. On 21st January 1919 Sinn Fein members of the Dail declared Irish Independence.

Almost immediately guerrilla warfare broke out, intensifying after the British Government declared the Dail and Sinn Fein illegal in September 1919 until, after considerable loss of life on both sides, the Government of Ireland Act was passed in May 1921, partitioning Ireland and establishing a separate Parliament of Northern Ireland, which met for the first time in June 1921. Following partition a truce was arranged on 11th July between the British Government and Sinn Fein representatives and, following lengthy negotiations, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in London on 21st December 1921, provoking civil war between Irish Republicans who supported or opposed partition. A year later Britain officially recognised the Republic of Ireland.

Altogether some 261 British servicemen lost their lives during the Irish War of Independence, together with 410 officers of the Royal Irish Constabulary and 43 Ulster Constabulary men, as well as at least 500 IRA members and 750 civilians. The worst violence was in the first half of 1921 and it was during this period that 2nd Lieutenant Geoffrey Turner Hotblack and Gunner Bernard Francis were killed.

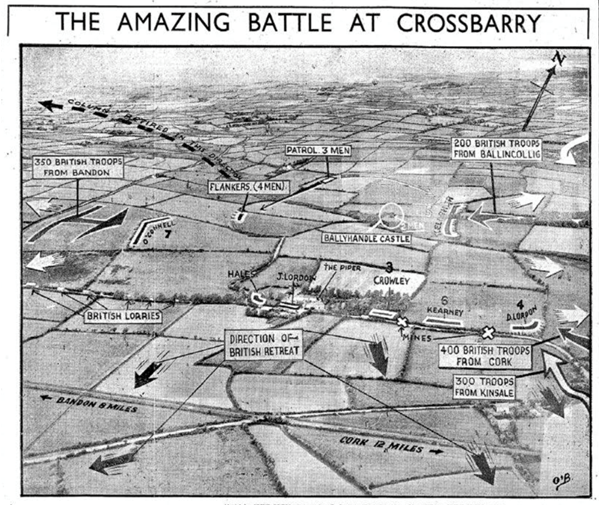

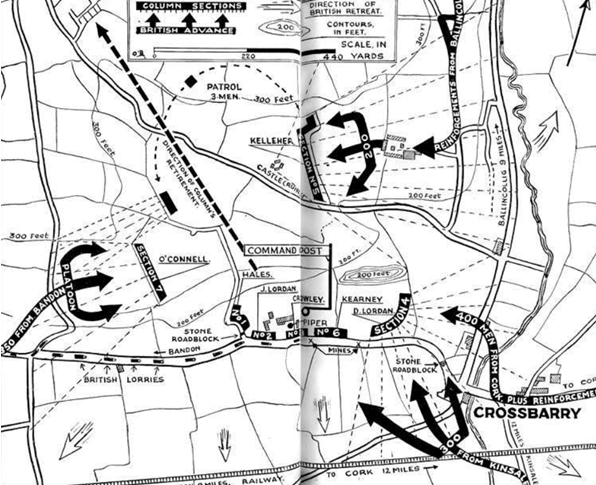

According to Irish sources the Crossbarry ambush on 19th March 1921, 12 miles south-west of Cork, came about as a result of over 1000 British troops attempting to encircle an IRA brigade, whose whereabouts they had discovered from a prisoner under interrogation. Soldiers of the 1st Essex Regiment, travelling in motor lorries from Cork, were seen to be well ahead of other British units converging from other directions, and therefore vulnerable to attack.

An ambush was quickly arranged at Crossbarry cross roads where, at about 7.30 am the three front lorries of the column were destroyed when the bridge over which they were passing was blown up by the IRA as an Irish piper played “Wrap the Green Flag Round Me”. 2nd Lieutenant Hotblack died as a result of a bullet wound to his spine during the fighting which ensued.

According to one of his platoon 'We were on patrol under 2nd Lieut. Hotblack. We saw the rebels firing in the opposite direction. We moved up and took position and fired on the rebels in reverse. Three or four rebels dropped. 2nd Lieut. Hotblack then decided to take up position on their flank. In doing so 2nd Lieut. Hotblack was shot by rebel fire. We laid [him] down behind a bank and then took up position to cover him and awaited reinforcements. On the reinforcements arriving we took 2nd Lieut, Hotblack on a gate to Crossbarry village. I saw about 100 rebels altogether.'

Born in Norwich in 1900 and educated at Brighton College he followed his three elder brothers into the army, entering Sandhurst just before his 18th birthday in September 1918. His parents lived at Rocklands, The Avenue, Lewes. They came to Lewes in 1912. His father was chairman of Kidd and Hotblack, Brewers of Brighton. According to one Irish witness, who had been arrested by him as an IRA suspect in December 1920, he spoke with a pronounced stutter. He had been in Ireland just over a year when he was killed.

Five other soldiers of the Essex Regiment died in the same ambush as well as three RASC drivers and one Royal Irish Constabulary driver.

The New York Times reported seven IRA men killed and 20 taken prisoner.

A monument to the 104 men of the IRA West Cork Brigade who carried out the attack stands on the site of the battle, which was one of the largest of the Irish War of Independence.

According to his commanding officer at the East Ferry Coastguard Station, 3 miles east of Queensferry (now Cobh), Cork, on Saturday 14th May 1921 Gunner Bernard Francis was abducted by armed men and shot whilst out walking 'with a chum… I searched the whole country round but was unable to find any trace of the murderers.'

Irish sources state that he and his fellow Royal Marine were taken by members of the Ballinacurra Company of the Midleton Battalion, Cork No. 1 Brigade, following orders to the IRA in Cork that 'all British military personnel in uniform should be shot at sight whether they were armed or unarmed'. Altogether seven British soldiers were killed that day. Gunner Francis’s body, with that of his chum, were dumped in a local quarry.