Betty Stevenson – ‘the Happy Warrior’

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Betty Stevenson – ‘the Happy Warrior’

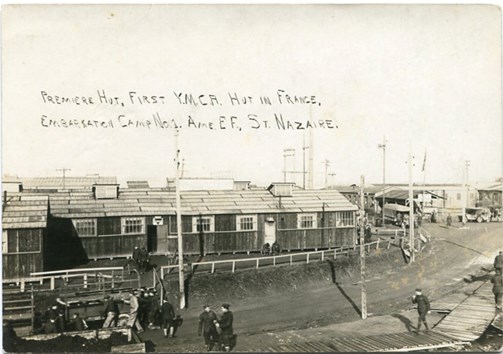

Within days of the war being declared the YMCA established recreation centres in the United Kingdom – largely near railway stations and other places where large numbers of troops were likely to be gathering. By the end of 1914, similar centres had been established at Le Havre in France and later in other areas of France.

Above: The first YMCA Hut in France

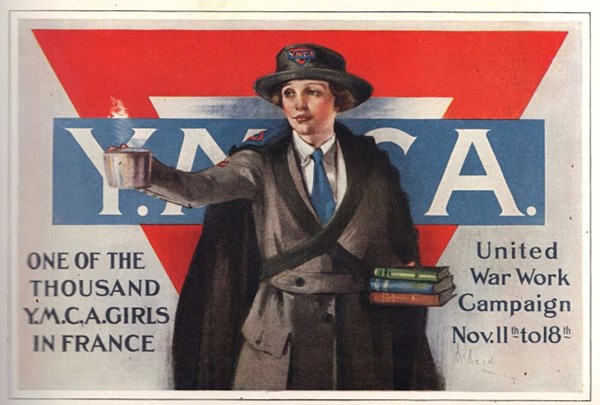

Later in 1915, centres were established ever nearer to the frontline in France and Belgium. The centres were largely operated by volunteers, many of whom were young women. In addition women carried out other roles in driving relatives to visit the wounded in hospital in northern France.

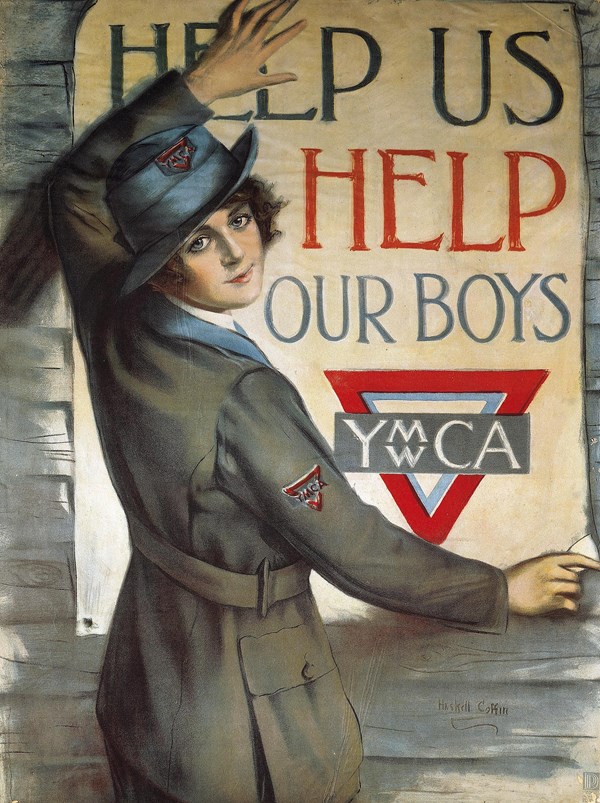

Above: A YMCA poster

Above: ‘Help our boys’ – a YMCA poster

Bertha Gavin Stevenson, known as Betty, would become one of these volunteers. She was born on 3 September 1896, the only daughter of Arthur and Grace Stevenson, and had one brother, James, born in 1901.

Above: Betty as a child

Her father, trained as a solicitor, was later described in Census documents as a Railway Estate Agent and the family were clearly middle class, with three servants in their household. Betty was educated at home until she went to boarding school at St George’s Wood School in Haslemere, Surrey at the age of 14. From school, she went to Brussels to study music.

Betty’s initial foray into voluntary work was in 1914, when she went to London with her parents to assist in the relocation of Belgian refugees camped out at Alexandra Palace, London to Harrogate, the town in which the family had lived since 1913.

Above: Belgian refugees at Alexandra Palace – Photo Hornsey Historical Society

Two years later, in February 1916, Betty would join her aunt as a canteen worker in the St Denis YMCA hut on the outskirts of Paris, lodging in the Hotel Magenta in Boulevard Magenta.

Above: Boulevard Magenta, Paris Photo – Paris-unplugged.fr

From Betty’s diaries and letters, it is obvious that she enjoyed being in Paris:

‘I do think Paris is too lovely for words, better even than Brussels but I expect that’s because I have something real to do’

The huts provided food and entertainment to the troops in France. Her mother, who would come out to work alongside Betty in April 1916, described their work:

‘The Y.M.C.A. Hut where we worked was a few miles due north of Paris, in a very poor and not too reputable suburb. It was set in the middle of a cinder-laid compound, and was surrounded by M.T. workshops, in which were motor-lorries and motor-waggons of every description, and wounded cars sent down from the Front for repair. ….. One other lady shared the work of the hut with us. We used to work in alternating morning and evening shifts, i.e. one day Betty and I worked from after breakfast until 2.30 or 3.30, and the next day we worked from 5 to about 10. Here let me try with a feeble pen to give some glimpse of the happiness we had inside that hut. It was absolutely the one bit of brightness in the men's lives there. It stood for home, and the decencies and amenities of home, and we knew it, and it helped us to keep going. I know it can be said of countless Y.M.C.A. Huts all through these past four and a half years, that they were little lifeboats on a vast sea of warfare, but I can never think that in any spot in the whole of the war area was a hut so needed as ours was.’

Above: Entertainment in a YMCA hut

Travel to and from the hut to their lodgings had proved challenging and eventually Betty and her mother solved the difficulties by obtaining a second hand Ford car, which Betty quickly learned to drive. In August 1916, Betty and her mother spent a leave in Finisterre, Brittany, with Betty’s father and brother joining them for what would turn out to be their last family holiday together. During this time, her mother recounted:

‘…… our Y.M.C.A. chief wrote and offered us a "boss job" in what Betty called a "really thrilling place" much nearer the front line, because, as he said, "we had done our duty in hard circumstances" and I must confess that, left to myself, I would have accepted the new offer. But Betty sat and meditated about it, on the sunny plage, and she said : "Well, I know it would be thrilling to go to Abbeville, but I vote we go back to St Denis. We know how grateful the men are, and they know us now so well, and I somehow feel it would be mean to leave them for a new place." So we decided to go back to our old hut.’

Betty and her mother returned home to Harrogate in November1916 but Betty was soon anxious to return to France. This time, she wanted to work as a YMCA driver responsible for transporting relatives from England who were visiting the wounded in hospitals. Although she was younger than the YMCA rules specified for such work, finally she got her wish in April 1917 when she was posted to Etaples as a driver. In her first letter home, Betty described her initial lodgings in Etaples:

‘I am billeted in a house with a nice view over the river on the main road. I think I am the only female there, but I’m not sure. There are some Y.M.C.A. men there, and an English officer downstairs. The house is kept by an old man and his wife —filthy dirty, but very amiable. My room is the dirtiest I have ever seen, but is a nice room all the same, and the dirt isn't the sort that matters.’

Later, Betty would move into a villa with four other women.

Part of Betty’s work was to transport relatives visiting dangerously wounded men in the hospitals around Etaples.

‘I have been driving a relative about to and from hospital. Poor man, his son died just half an hour before I arrived to take him back to the hostel. This relative business is simply too pathetic for words. We have to drive them to the funerals. A whole string of men headed by the padre, and then a procession of coffins draped in a Union Jack, laid on a little carriage and wheeled by two men; then the service round the grave and then the Last Post. A photo is always taken of the grave and given to the relative.’

Above: Betty and her lorry, which she named Archie

Above: Betty in uniform

‘I have just been on a long run to Abbeville where Uncle Lionel was. Started at 1.30 and got back at 6.30. Hard driving all the time. It was thrilling. I am driving a lovely Ford now, with a new electric lighting set on it, and I feel no end of a swank.’

Betty often drove concert parties and other visitors to YMCA Huts in addition to taking relatives to hospitals, but also carried out other duties:

‘I have been getting up at 5 a.m. and going out to the sidings, and selling things to the men going up the line. Train after train of them. It's the most interesting work I have ever done, but most horribly sad. I want to weep most of the time, but find myself making jokes and laughing with the men when I feel most dismal. I'm sure we cheer them up. I can't sell quickly enough. I get on the footboard of the train and they all fight for things. What with English, French, and Belgian money, it's most awfully difficult to keep one's head and remember the rate of money exchange.’

Betty’s 21st birthday in September 1917 saw her in Boulogne, going on leave for birthday celebrations in London:

‘The birthday party lasted for three days, and was called " The Great Push " by one wag who helped at it. On Wednesday, twenty-four of us sat down to a festive dinner. Birthday speeches were made, and I do not think anyone present will forget Betty's happy smiling face, as she sat at the end of the long table, beside her father. Nor will some of us ever forget how she had to come down to her party, wearing what was not the dernier cri : the pretty frock which was a birthday present, and was laid out ready for her in her room, did not quite ' fit ' alas !’

Back in Etaples after her leave, Betty continued to be kept extremely busy but came down with influenza in November 1917. A letter to her father, written in January 1918, suggested that she had not shaken off the illness:

‘I am going back to my car when I'm fit again, and am coming home in the beginning of February. I shall either ask for indefinite leave, or hand in my permit for a month or two, I'm not quite sure when. I've never really got rid of that silly chill I got, so everyone advises me to have a good big leave, and get braced up for the Summer, so I think I shall. . . .I'm writing such drivel, but my pen seems to be running away with me, but I don't really feel like it a bit. I feel " mentally unsettled "—what a hideous combination of words, but I can't think of a better. ‘

Her mother wrote of Betty’s homecoming:

‘Betty crossed from France on Thursday, 21 St February 191 8. Major M. escorted her. They had a great railway journey up from Folkestone ; the carriage was full of brass hats, and Betty said they all behaved like schoolboys, and played all sorts of games. On Friday, the 22nd, she came home. I met her, and when she jumped out of the train, I thought I'd never seen her look so sweet. She had on her long khaki overcoat, and she had two service stripes on her sleeve this time—I was so proud of her. I had made her room look so pretty, and had made her new tablecovers, and a new lampshade, and she had a lovely new chest of drawers, and the room was full of flowers, and looked, as she said, "just heavenly."

Above: Last home leave

‘There is nothing but happiness in the remembrance of that last leave—there was a great number of visitors, much loved aunts and uncles and friends on leave, and a good deal of tennis. But best of all remembrances to me is one walk across the Stray, when she said to me, " No girl ever had such understanding parents as I've got." And when I said, feeling enveine for original remarks, and full of pride in her, " You know. Bet, I do like you so, as well as loving you : you're such a good friend, even if you weren't my daughter, bless you," she was delighted with the idea of our being friends’.

Betty’s return to France was delayed by the Spring Offensive which started on 21 March 1918, and it was not until early May 1918 that she returned to join the Lion d’Argent Hut, in Etaples.

‘The people who work at the Lion d’Argent with me are ever so nice, and I like the work very much, and there is heaps to do. . . .’

Her return coincided with a number of air raids carried out by the Germans – although Betty showed no sign of fear about these, as she wrote home:

‘I don't know whether you hear much news of this part of the world—I imagine not. Anyhow we are all well and flourishing, though we don't sleep here. We all go out and sleep in P.-P. and in the woods—we find it " healthier." We are having a great time. Chappie and I and another girl share a room in a villa we have taken over away in the woods. We leave here the last of anyone. Sometimes on bicycles and sometimes in cars. Some of us are in tents and huts, and the men in the woods and on the open verandahs of the house. It's a great stunt.’

But on 31 May 1918, the Etaples Administrative District General Secretary—Adam Scott Y.M.C.A., B.E.F., would write to her parents:

‘Dear Mr and Mrs Stevenson,—You will have had from the Military Authorities the sad news of Betty's death last evening. I scarcely know how to begin to write you. She was the darling of the whole Base staff, and was so loved by everybody that we are all sort of dazed by her loss. She had been busy all day, in the afternoon at the Lion d'Argent, and later, along with Mrs Stewart-Moore, with the refugees at the station. Owing to a car breakdown, a group of workers were later than usual in starting for Les Iris, where we had been sending all our ladies to sleep recently for greater safety. A very early raid sent us all to the cellars, and after it was over we put the party of ladies on two cars to send them out of the danger zone in case the planes returned. We were held up half-way, and a second raid came over, forcing us all to take shelter under the banks by the side of the road. Everything went well until an enemy plane, just as the raid was finishing, dropped several bombs in open country near us, probably in order to get rid of them before returning. One bomb killed Betty instantaneously, and wounded two other workers, who are in hospital. I was by her side within a minute of the bomb falling, but nothing could be done. She could not have felt it, as she was shot through the left temple. She was taken to hospital at once. The funeral will take place, we expect, to- morrow, and will be with full military honours as an officer of the British Army. We cannot realise she has gone from us yet, and her place in the hearts of us all will not be filled. Only the other day we were talking of her as the sunshine of the whole place. Knowing how much she has been to everyone who knew her out here, we can have some small feeling of what her loss must mean to you both. I can only say on behalf of us all how deep is our sympathy with you all. We mourn her as a very dear friend. Mrs Stewart-Moore was with her all through, and will doubtless be writing you.

Believe me, yours very sincerely, Adam Scott. A.P.O., S. II, B.E.F.’

Above: Betty Stevenson, Young Men's Christian Association. Killed by shrapnel from an enemy bomb on duty in Etaples 30 May 1918. © IWM WWC K4-1

Another letter from a fellow YMCA volunteer described her last moments:

‘It seems useless for me to try to say how sad we have been made by her death ; she was known and loved by everyone at Etaples on account of her happy smile, which never left her. She was not nervous at all. I was surprised at her calmness and steadiness. I had done all I could to make her as secure as possible. She was wearing my shrapnel helmet, and we were well down at the bottom of the bank. She suffered no pain at all ; I did not feel a tremor, but after the noise and dust of the explosion had died down I spoke to her, asking her if she was all right, and she did not answer. We got her to the hospital at once in a car, but the doctors could only tell us that she must have been killed instantaneously and painlessly. I am very glad to be able to say that she was smiling in death.’

Betty was buried in Etaples Military Cemetery with a ceremony described in a letter to her mother;

‘We have just come back from putting the little one in her last resting-place. She had a soldier's funeral and a beautiful service, and some lovely wreaths and flowers, and I can assure you there was not a soul there whose heart did not ache with sorrow for you. ……..I must tell you about the funeral, as I am afraid no one properly did. We all went to the soldiers' cemetery and lined up at each side of the little chapel, and waited there till they carried her out, with a Union Jack rolled round just like a soldier. We went up and put our flowers and our love on the top, and the little procession started on its way down, the chaplain in his white robes in front, soldiers wheeling the little carriage ; and the bugler ; and then we came in twos. I walked directly behind with Effie, and then the -drivers, and Lady Cooper and Mr Scott, and all the others. The Burial Service was read and the 90th Psalm, and the chaplain spoke a few words, telling of her work, and how she had died for her country like a soldier. It was a beautiful and touching service, and was attended by her fellow-workers, people from Boulogne, her soldier friends, and the French sent a French Staff Officer from G.H.Q.,! to pay his respects with the others ; he stood, a splendid figure, and saluted as she was carried by. We did not have a hymn as it was a military funeral, but it was a beautiful service, and we had some verses which I have marked in my Bible to show you. And then at the last the bugler sounded the Last Post, and there was not a dry eye amongst us all, and I held on tight to my courage, and prayed so hard for you. Then they lowered her gently in, and we stepped forward and sprinkled her little bed with flowers. Dear, it was beautiful, and it is a lovely spot with the river and the sea, and the woods all over the other side. She went home with all her courage, and a smile on her dear lips, and her lovely soul had gone without suffering.‘

Above: The grave of Betty Stevenson is tended to by a member of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in a graveyard at Etaples, France. © IWM Q 8028

Above: The inscription on Betty’s grave is ‘Croix de Guerre avec Palme. Aged 21 years. The Happy Warrior’

Above: The Croix de Guerre

A memorial was also erected in Christ Church Harrogate

Above: A memorial to Betty in Christ Church, Harrogate (IWM)

Sources:

Betty Stevenson, YMCA – published by Longmans, Green & Co 1920

Imperial War Museum

www.ymca.org.uk

Article by Jill Stewart. Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association