Death of a Spy: Charles Simon : 7 June 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Death of a Spy: Charles Simon : 7 June 1915

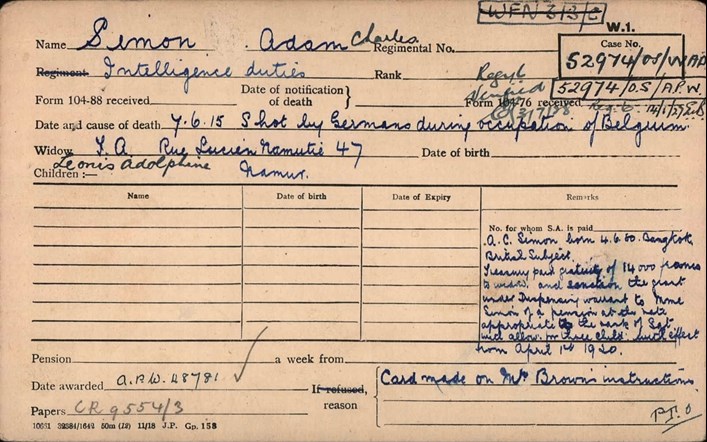

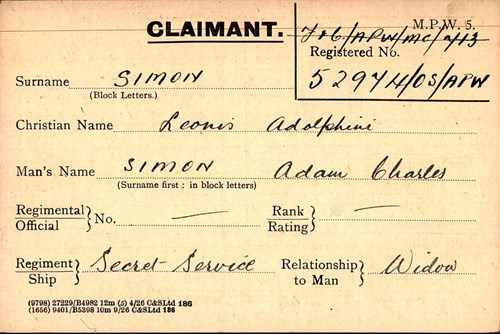

‘Project Hometown’ has brought to light many fascinating, tragic and sometimes uncomfortable stories. However, one of the most unusual cards is that of a civilian who received an award for gallantry and whose dependants were granted a military pension.

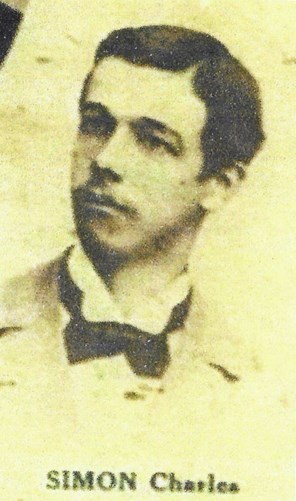

Adam Charles Simon (who preferred to be known as Charles) was born in Bangkok on 4 June 1880. His father was Charles Thompson Simon, a Belgian, whilst his mother Mary Anne Burke was British. Both parents were born in Bengal, India. By 1900, his father was managing a marble quarry in Ipoh, Perak, Malaya. His mother, who had been suffering from tuberculosis for several years, died in Singapore on 22 May 1900. His father died in Ipoh during 1908. Like many children of his time, whose parents lived in the Far East, he was sent to Europe to be educated, in his case, a boarding school in Bordeaux. He later trained as a draughtsman. On 3 April 1907, he married Leonie Delphine Houdretin Namur. Their home was to be at 10 Rue de Balart, Namur. By 1914 they had two children; Marguerite born 7 April 1909 and Roger born 9 November 1910.

Following the invasion of Belgium in 1914,as a British citizen Charles was deported to Germany but was subsequently allowed to return to Namur. By then Justin Lenders, described as an Industrialist, had created what was known as “The Lenders Service”. This collected details of German troop movements and passed them on to the Allies. This was essentially the movement of military trains recorded as they passed certain locations. Charles joined this group which with himself consisted of seven men and a woman. Having obtained the information, they had a problem - how to get it to the Allies. To achieve this, the only female member of the group, Louise Derache, became a butter merchant. Equipped with a double bottomed basket, she went over the border to the butter market in Maastricht, Holland, delivered her intelligence to British agents and returned with false passports. This method was also used by other groups providing information. The Germans, aware of what was happening, introduced fake couriers into the system, one of whom made contact with Louise and betrayed her. Her betrayal led to the arrest of all the other members of The Lenders Service on 30 April 1915.

They were imprisoned at Saint Leonard prison in Liege to await trial. Charles occupied cell 121. Life was not comfortable: meals consisted of 250 grammes of bread and half a litre of thin gruel served midday and evening. The group came before a military court on the 5th June 1915, when they were all sentenced to death for espionage. They were to be transferred to Fort Chartreuse next day for the sentence to be carried out on 7 June. The German authorities, anxious to avoid demonstrations or any attempts to rescue the prisoners, used the vehicles utilised for taking rations to the fort for the transfer rather than prison ones.

Above: Fort Chatreuse. Cell block on left. The arch on the left led to the execution ground (courtesy: F de Look)

Above: Cell block where prisoners held awaiting execution (courtesy: F de Look)

On the eve of his execution Charles wrote a long letter to his wife, the main theme being forgiveness. He gave advice on the upbringing of the children and where to get guidance on such matters, also that she should remarry. On forgiveness he said to his wife "Teach the children not to hate and to trust in heavenly justice” and to his son he said “Do not hold a grudge, but have noble feelings, be just, even towards your enemies." He expected his body to be returned to Namur and he cautioned his wife against spending too much money on the arrangements.

On the morning of the execution the prisoners were taken from their cells and escorted to the place of execution by the garrison commander, a military observer, a doctor and a priest plus the guards. The firing squad of ten men was waiting for them. Blindfolded, they were tied to a post and shot. Last rites were performed by the priest and the bodies placed in coffins. After a brief funeral service, they were buried, thus denying Charles’ wish to be taken back to Namur.

It is reported that the firing squad was unaware until the last minute that a woman was to be executed. Unsettled, their aim was poor, and as a result she was wounded in the legs so a pistol shot to the head was necessary as a coup de grace.

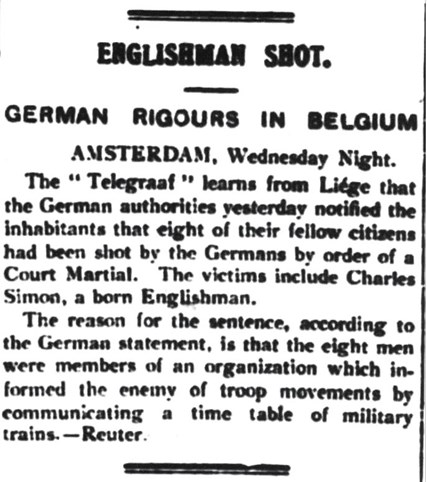

The next day the German authorities posted notices on the wall of Liege announcing the executions. These did not attract much attention outside of Belgium. A brief report put out by news agencies wrongly stated that eight men had died thus Louise’s death went largely unnoticed. A typical press item is shown below from Reuters.

On 21 June, just two weeks after her husband’s death, Leonie gave birth to a daughter, to be named Isabelle. Leonie’s circumstances during the war years are not known but they cannot have been easy. There is speculation that she tried to obtain a British passport. This would have enabled her to travel, via Holland, to join relatives in England but this, it is alleged, was blocked by the Germans. However the National Archive at Kew holds a file (FO383/374) for 1918 which does contain such an application, supported by her mother in law’s death certificate to demonstrate the British connection. (Unfortunately. the current pandemic precludes the examination of this file).

After the war Charles was made an honorary sergeant in the British army with Leonie being granted a military pension based on that rank. She also received a lump sum of 14000 francs - worth about £560 at the time (£56,000 at today’s values).

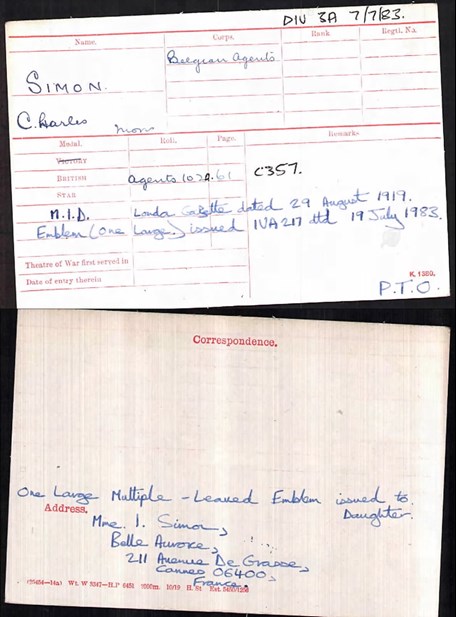

The London Gazette of 29 August 1919 announced he had been mentioned in dispatches and earlier that month he had been awarded the British War Medal and Victory Medal. There also now exists in the Bouge district of Namur, the Rue Charles Simon.

During three days in mid October 1919, the bodies were exhumed for return to their next of kin. While each group executed was buried at separate locations and in coffins, the coffins were not marked. This meant that relatives were required to attend the exhumations in order to identify the bodies. On 25 October the bodies were taken back to Liege, carried on horse drawn gun carriages for reburial with full military honours.

The execution ground is now a memorial park. There is a special memorial marking the spot where the executions took place. On a lawn of honour are 48 stone crosses each bearing the name of one of those killed.

Above: The Lawn of Honour (courtesy: F de Look)

Finally a minor mystery. Charles’s Medal Information Card is endorsed that on the 19 July 1983 one large multi leaved emblem was issued to his daughter Isabelle, who was living in Cannes. It could be that she had simply asked for replicas of her father’s medals but the fact that a large multi leafed emblem was issued may suggest a presentation of some kind.

Acknowledgements

Medicins de la Grande Guerre http://1914-1918.be/

Bel-Memorial https://bel-memorial.org/

Humberston, David Female Spies of the Great War

Article contributed by Jeff Ward