Drowned close to shore: the loss of two American Troopships in 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Drowned close to shore: the loss of two American Troopships in 1918

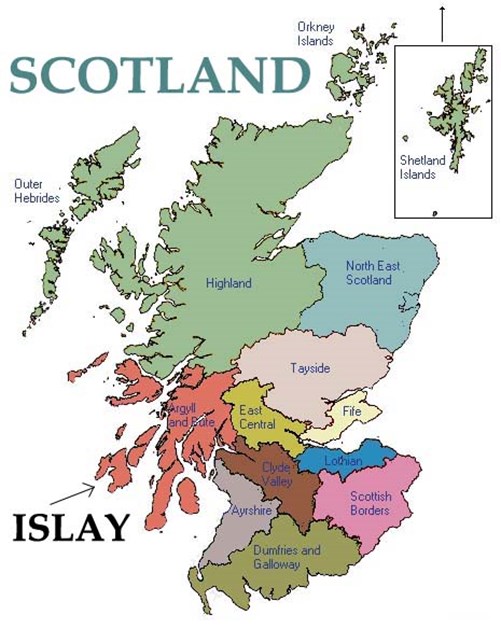

In 1918 the small island of Islay off the west coast of Scotland would witness the full brunt of the sea war on not one but two occasions.

Above: Islay is the most southern of the islands in the Inner Hebrides, known as ‘The Queen of the Hebrides’.

The first of these was on 5 February 1918 when the Troopship Tuscania was torpedoed by UB-77 at 7.40pm. The ship was part of convoy HX20, comprising fourteen ships bound for Liverpool, with over 2,000 American troops on board and a crew of almost 400. The convoy left Halifax, Nova Scotia on 27 January 1918.

Above: The Tuscania. Prewar she had been a luxury liner of the Anchor Line.

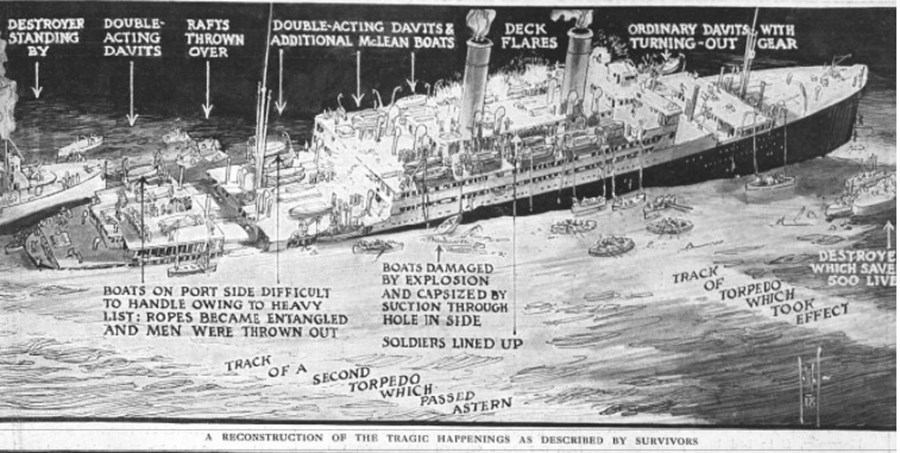

After ten days, land was finally sighted by the Tuscania – the island of Islay. Meantime UB-77 had travelled through the Pentland Firth and was heading towards the northern coast of Ireland when she sighted the Tuscania on 5 February 1918. Two torpedoes were fired – the second missed completely but the first hit the Tuscania near the engine room. Within minutes, she listed to starboard. A number of lifeboats were damaged in an explosion, and also the list to starboard made it difficult to launch the lifeboats on the port side of the vessel. Three escort ships from the convoy – Pigeon, Grasshopper and Mosquito - went to Tuscania’s assistance and assisted in the evacuation of around 1,500 men in the four hours before the ship finally sank but many would perish on the rocky shores of the island. In all, a total of 166 soldiers and seamen lost their lives. Many of the casualties were soldiers from the 20th Engineers.

Above: a reconstruction of the fate of the Tuscania which appeared in The Graphic in February 1918

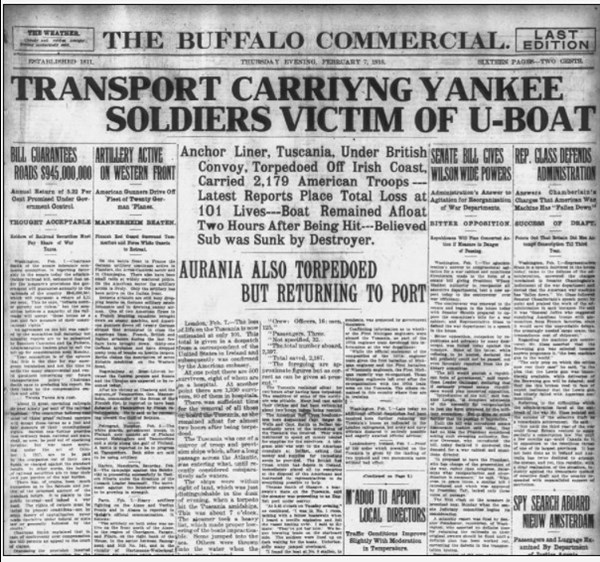

The loss of the Tuscania was a particular shock for the American people with American newspapers carrying accounts of the tragedy. British newspapers also carried many accounts of the sinking, with stories from survivors.

Above: American newspaper coverage of the loss of the Tuscania

On 6 February 1918, the islanders would find many bodies washed up on the shore. Lord George Robertson of Port Ellen, whose maternal grandfather was the police sergeant on Islay at the time of the sinking, recounted:

“My maternal grandfather, Malcolm MacNeill, had the distressing job of reporting what had happened and attempting to identify the bodies, noting any distinguishing marks that could help identify the drowned men. There were so many bodies that their descriptions filled 81 pages in his notebook. When they were finally buried, it fell to my grandfather to correspond with the families in the United States who were desperate to know more about the fate of their loved ones. They wrote with information which they hoped could be used to identify the bodies of their sons, husbands or brothers, and in an extraordinary example of compassionate public service, my grandfather replied to each letter, providing what information he could”.[1]

Any survivors arriving on the island were taken in by the islanders – in one case, farmer Robert Morrison had as many as 90 survivors crammed into his farmhouse. Many of the islanders who had taken survivors into their homes would receive letters of thanks from relatives.

Those taken on board the escort vessels were landed in Ireland.

There was much anxiety in Glasgow on the news of the sinking as most of the crew came from that city. Many relatives gathered outside the Anchor Line offices in St. Vincent Street to await any news. By 9 February 1918, press reports would indicate that there were around 50 crew members unaccounted for but of those, some had been landed ‘on an island on the west coast of Scotland’.

Above: Relatives of crew members waiting for news after the sinking of the Tuscania

Press reports would later tell of distressing scenes when women broke down in grief when their husbands did not arrive back at St. Enoch’s Station with the Captain and around 180 crew members.

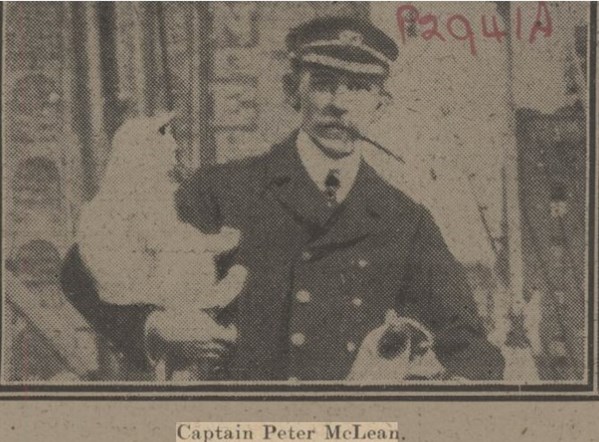

Above: Captain Peter McLean of the Tuscania. Pictured in the Daily Mirror in February 1918. He was one of the last to be rescued from the Tuscania.

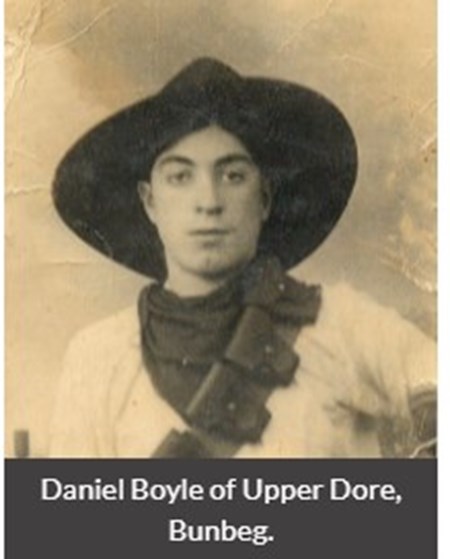

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records that 47 crew members died on 5 February 1918. One of these was Daniel Boyle from Bunbeg, Ireland (although his name on the CWGC website is stated as Denis).

Above: Daniel Boyle from Upper Dore, Bunbeg Photo – donegalnews.com

One of the oldest members of the crew to perish was Trimmer Charles Mullen, aged 58, the husband Alice Mullen from Glasgow. He is buried at Kilnaughton, two miles outside of Port Ellen.

Above: the headstone of Trimmer Charles Mullen in the Kilnaughton Military Cemetery on Islay.

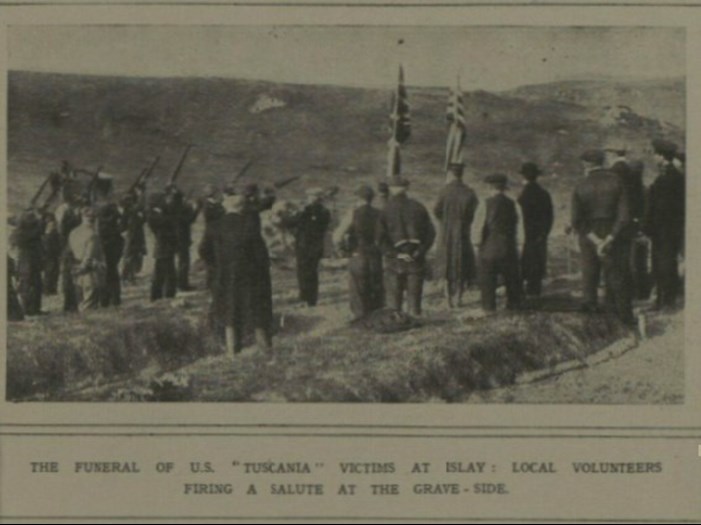

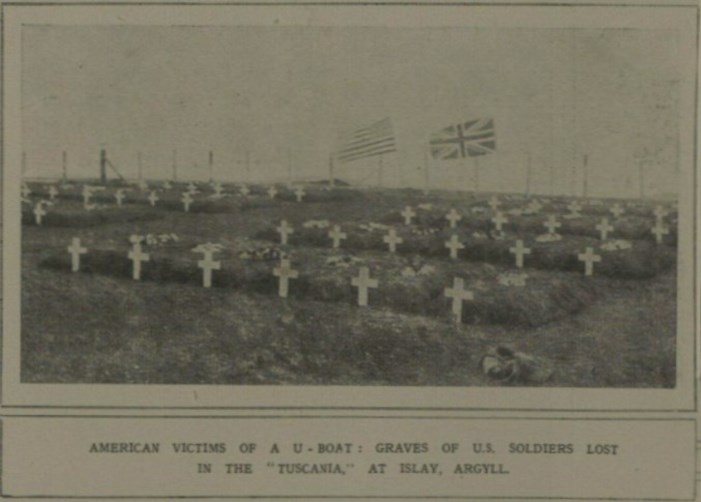

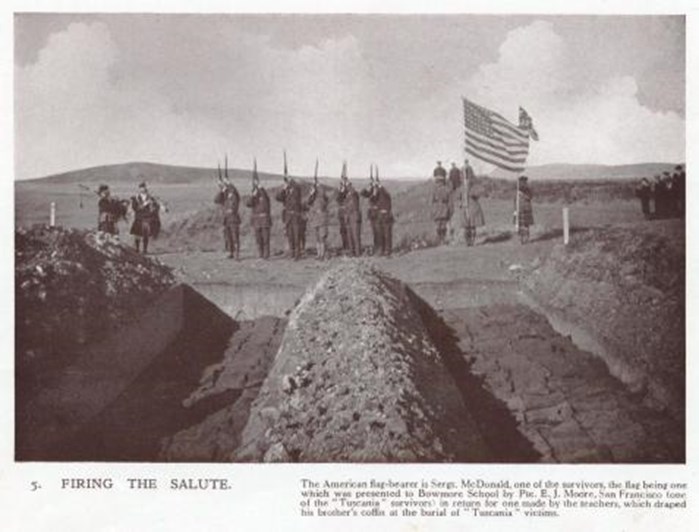

The bodies of the American soldiers washed up onto the shores of the island were also initially buried at Kilnaughton. There was no American flag on the island so local women carried out work to recreate the ‘Stars and Stripes’ – they finished work on the flag at 2.00am in the morning of the first of the funerals.

Most of the American graves were later repatriated to America after 1920, with only one grave, that of Roy Muncaster, remaining on Islay at the request of his family. A native of Colorado, Roy was of nine children born to English immigrants William Muncaster and Elizabeth Ewing.

Above: Roy Muncaster. Photo - content.lib.washington.edu

Above: The cemetery on Kilnaughton Bay, with Port Ellen Lighthouse. To the left is Kilnaughton Military Cemetery.

Above: Kilnaughton Military Cemetery on Islay. Photo - CWGC

The loss of the Tuscania would be overshadowed by the even greater loss of life when SS Otranto collided with another vessel in October 1918, off the coast of Islay.

Above: the Otranto, a requisitioned armed merchant cruiser, acting as a troopship carrying American soldiers to Britain.

In poor visibility and very rough seas, she was involved in a collision with HMS Kashmir, another troopship, in the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and Scotland, off the coast of the Island of Islay.

The Otranto sustained severe damage below the waterline, but the seas were so mountainous at that time that it was impossible to launch the lifeboats. Reports vary on the numbers, but at least 350 US ‘doughboys’ and 96 British sailors lost their lives. The destroyer HMS Mounsey managed to take off many troops, thus preventing a much greater loss of life. Lt Commander Francis Worthington Craven of the Mounsey would later receive the DSO for his actions in saving the lives of many of those on board the Otranto.

Above: Lt. Commander Francis Worthington Craven of HMS Mounsey. After the war, he joined the Royal Irish Constabulary and was killed in in an IRA ambush on 3 February 1921. Photo – www.kenspratlin.com

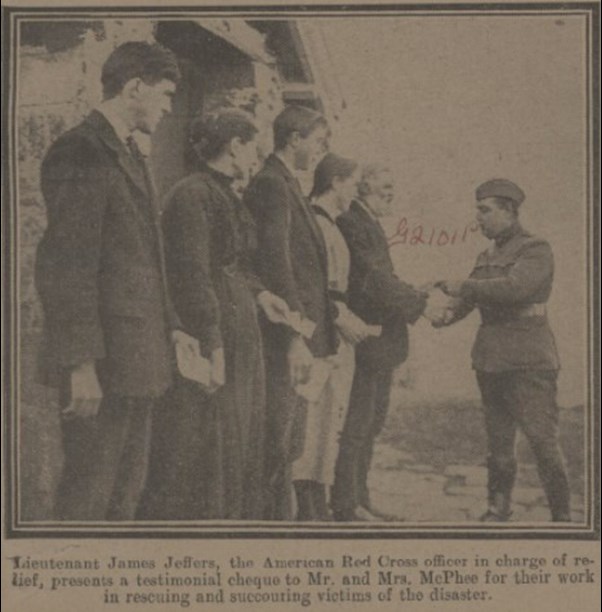

The Otranto then hit rocks and became grounded, before eventually breaking up. Many stories about the assistance provided by the islanders to the survivors of the wreck would be reported later in the press. One such account was the contribution of the McPhee family who rescued a number of American soldiers from the sea and then cared for them in their small croft. Later reports recounted that that the McPhee family later received a testimonial cheque from the American Red Cross.

Above: A Daily Mirror picture showing the McPhee family receiving a testimonial cheque from Lt James Jeffers of the American Red Cross.

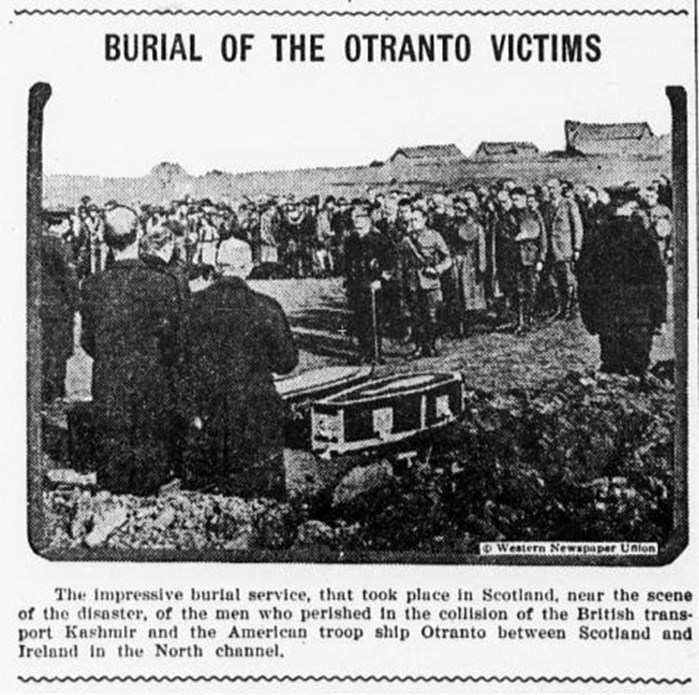

The dead were buried at Kilchoman Military Cemetery on Islay.

Above: the burial of casualties from the Otranto

Above: Captain Ernest George William Davidson, the Captain of the Otranto who perished in the sinking. Photo – www.submerged.co.uk

In 1920 the American dead were either repatriated or reburied in the American Military Cemetery at Brookwood, Surrey.

The American Monument was erected by the American Red Cross in 1920 six miles from Port Ellen on Islay and commemorates those lost from both the Tuscania and Otranto.

Above: The American Memorial on Islay. Photo - IWM

In May 2018, a number of memorial events were held on Islay attended by HRH The Princess Royal and her husband, Sir Tim Laurence.

Above: HRH The Princess Royal laying a wreath on Islay. Photo –Argyll and Bute Council

Article contributed by Jill Stewart

Hon. Secretary, The Western Front Association

[1] Quoted in The Herald – 30 January 2018

Further reading:

The Drowned and the Saved: When war came to the Hebrides. Les Wilson (Birlinn 2018).