Finding the Horses and Mules for the British Army during the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Finding the Horses and Mules for the British Army during the First World War

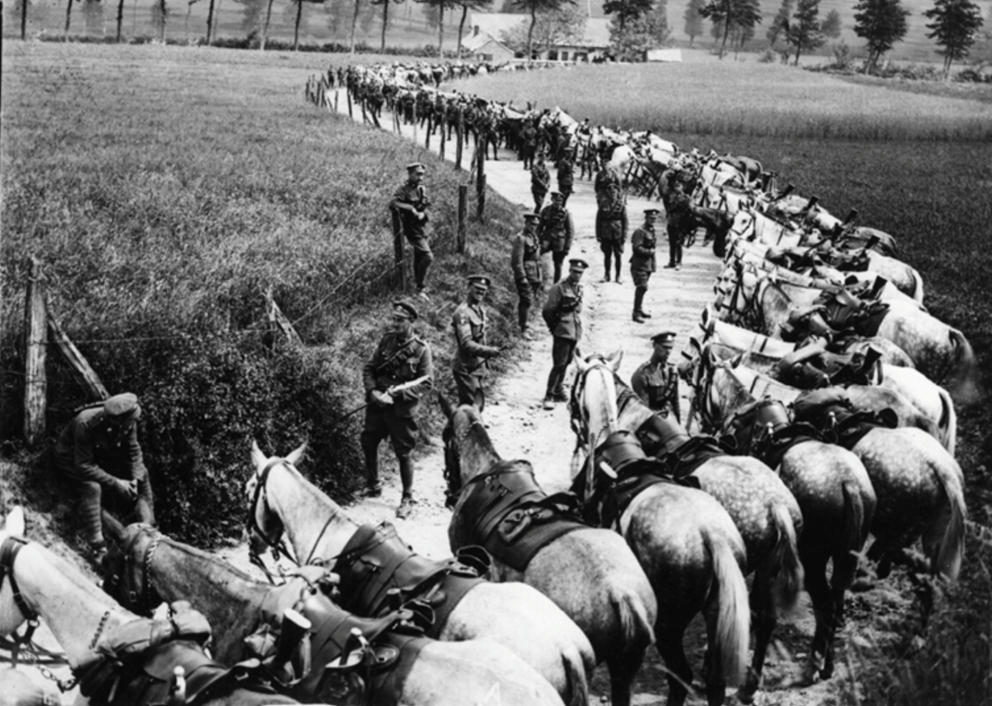

During the First World War, commandeering horses and mules was crucial to the British Army's mobilisation strategy. Despite the advent of motorised vehicles, horses remained essential for artillery and cavalry. By 1914, the Army needed to quickly amass 160,000 horses for the British Expeditionary Force, far exceeding the peacetime establishment. To meet this demand for horses, the British Army implemented an extensive Horse Mobilisation Scheme, which included purchasing and impressing horses from domestic and international sources, ensuring the Army was well-equipped for war demands. This article has been researched from original sources by Graham Winton and edited by Dr Martin Purdy

Horses and mules were not a marginal resource for the Army during the First World War - they were to play a crucial role in the Allied victory. Whilst motorised vehicles had started being introduced into the ranks in 1903, the horse still reigned supreme for artillery and cavalry.

In 1914, the Army had a completely integrated transport system featuring horses, mechanised vehicles, and rail networks. Still, the rapid scale of expansion required for mobilisation in August of that year meant that the motor industry could not meet the military demand.

As a result, equines had once again become the key source of motive power.

The normal army requirement was between 2,500 and 3,000 remounts a year, a comparatively small number for which there was no difficulty achieving supply within the UK. The problem was mobilising sufficient horses within ten days in the event of war for the Expeditionary and Territorial Forces and providing for a three-month supply of animals to replace a planned ‘wastage’ of 10 per cent in the field.

For general mobilisation, the Army required some 160,000 horses to be fit, trained, of the right class, type, and stamp, and in the right place at the right time.

The planned wartime establishment, including the first reserve for the whole British Expeditionary Force, was around 60,000, with a further 100,000 for the Territorials. This demand for horses and mules totalled around 160,000 for an army of s0 infantry divisions and 20 cavalry brigades, including the Cavalry Division.

The peacetime establishment of military horses based in the UK was about 20,000, and, in theory, around 20,000 more horses were registered with Army Horse-Reserve schemes. These schemes involved large horse owners, like the London omnibus companies, registering an agreed number of their horses with the War Office for an annual retaining fee of 10 shillings. In an emergency, these horses were sold at an agreed price.

When these two figures in the supply chain were added together, there was still going to be a shortfall of 120,000 horses - and this would have to be met by impressment.

Thankfully, by August 1914, the Army had already created a thorough Horse Mobilisation Scheme that recognised the three crucial elements required for success: organisation, supply, and care. This process started in the latter part of the 19th century. It took a huge step forward by creating a unified Army Veterinary Department in 1881, followed by a Remount Department and Horse Registration Scheme in 1887.

These changes enabled the military to cope with the colossal expansion of the service required for war in 1914—from finding the right personnel (such as vets, handlers and trainers, blacksmiths and farriers, grooms, and storemen) to sourcing equipment and feed (nose bags, blankets, harnesses, saddles, shoes, fodder, etc.) and establishing the necessary remount depots, veterinary hospitals, and transportation.

Above: Soldiers commandeering railway horses for Army purposes at Bexhill - taking the animals from their stables. Date: 1914 Media ID 14189285 (Mary Evans Picture Library)

The military horses would come from the nation’s working horse population and domestic horse breeding industry. Foreign markets such as North America were also used in a major conflict.

Regarding the more contentious issue of impressment of horses from civilian and business ownership, a purchasing scheme had been set up and trialled in 1913, and by April 1914, it was stated “that we were ready.”

The purchasing officers were generally retired officers, country gentlemen and Masters of Hounds, and civilian veterinary surgeons often carried out the work of inspection.

Impressment was never going to be evenly distributed among horse owners and businesses. Light draught and riding horses were in great demand for transport, cavalry, and artillery. In contrast, the number of heavy draught horses required on mobilisation was an insignificant proportion of those available in the country, so their withdrawal would not have any serious consequences.

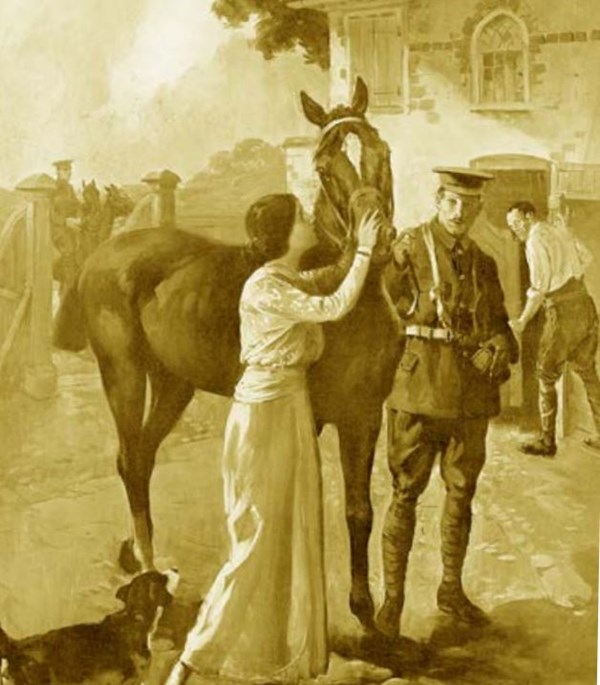

Above: Commandeered - Goodbye Old Friend by Dudley Tennant. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Above: Wanted for the Army. Collecting and branding horses for troops at the stables of W H Smith, the famous newsagents, on the outbreak of the First World War. Date: 1914. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

As might be expected, newspapers were quick to highlight the ‘outrages’ of military purchasers taking treasured family pets and horses vital to their owners' livelihoods, and this theme provided rich pickings for cartoons and sketches in popular periodicals.

It is undoubtedly true that some overzealous soldiers impressed horses that were too old, unfit and favourite pets, but a number of these were subsequently returned. For example, the horse of carrier Henry Mills in Oxfordshire was impressed and returned as too old.

Typical reports, such as that in a Western Super Mare newspaper, refer to ASC teams seizing horses from the shafts of carts and carriages in the streets—an action that would have been rare, if not highly unlikely.

Above: The Mills’ horse that was impressed and then returned as too old.

The family bakery and confectionary business of E.J.Bird and Son, of Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, is typical of many family stories handed down from the period: the family-owned six horses for delivering bread, and all were said to have been commandeered to serve in France. However, inspection of the records shows that only two were taken, and replacements for those were quickly found.

Stories like Bird and Son had an impact, but the evidence presented to the House of Commons strongly suggested that mobilisation was generally completed with minimal disruption.

The war effort, Government, and War Office clearly wanted to ensure that domestic, economic, and agricultural life was not badly disrupted, and the evidence available to modern researchers shows that they were mindful of that fact—indeed, it has been estimated that only about 17 per cent of the country's working horse population was mobilised for military purposes during the whole of the war.

The military planners' achievement in ensuring that the British Expeditionary Force headed to France in the late summer of 1914 with 152,000 horses—an increase of 700 per cent from the day the war was announced—and then continued to find fresh supplies of suitable animals, train, transport, and care for them is nothing less than remarkable.

Original research and article by Graham Winton. Edited by Dr Martin Purdy