Harry Lauder: The World's First Musical Superstar and Broken Parent of the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Harry Lauder: The World's First Musical Superstar and Broken Parent of the First World War

“Have you news of my boy Jack?" Not this tide. "When d'you think that he'll come back?" Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

Rudyard Kipling’s poem about his fallen son is one of the most well-known expressions of parental pain of the Great War, but few were more open about their grief at the loss of a child than ‘The World’s First Musical Superstar’ – the undisputed international king of variety, Harry Lauder.

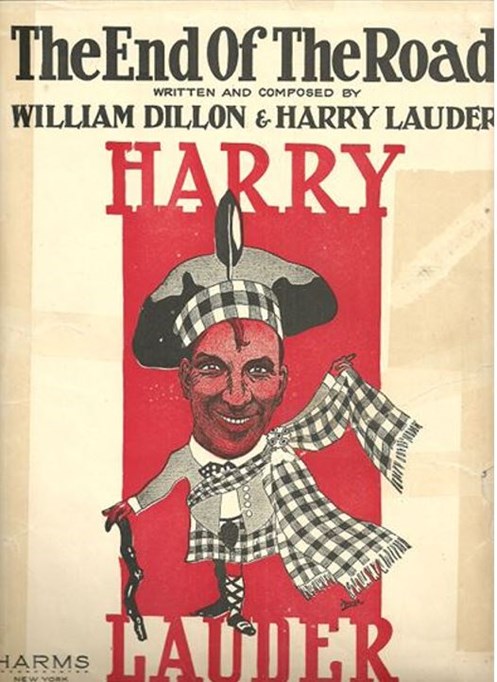

Above: Harry Lauder in the Highland regalia for which he was famous and his son John in official uniform.

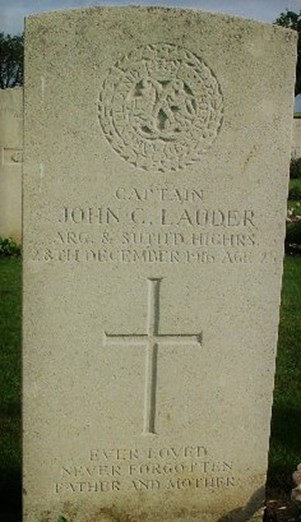

Lauder’s only child, Captain John Lauder of the 1/8th Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders, was killed on the Somme in December 1916. He had enlisted as a junior officer with his local territorial unit at the outbreak of war and survived the Battle of Festubert and Second Action of Givenchy in 1915 before being wounded in the arm by shrapnel from a shell burst. He did not get back to ‘Blighty’ but was treated at a base hospital before returning to his unit to be promoted to the rank of Captain.

Shortly after his promotion Captain Lauder was hospitalised again, this time suffering from “dysentery, fever and a nervous breakdown”. After a spell at a military hospital in Rouen, he was returned to the family home in Scotland and appeared to recover well - completing a period of home service as an instructor at a bombing school before returning to duty overseas. He would return to the front in September 1916. His father wrote: “The fear was in all of our hearts.”

It was a fear that was to prove well-founded, for Captain John Lauder was to be shot and killed by a German sniper on 28 December 1916, near Courcelette on the Somme. He was 25 years of age.

Above: Harry and his son pictured together early in the war.

The loss of their beloved son all but broke his parents, as Harry Lauder openly and movingly addressed in his 1918 memoir ‘A Minstrel in France’ about his personal and wholly remarkable mission of remembrance to the battlefields to find his son.

“It was on Monday morning, January the first, 1917, that I learned of my boy’s death,” he wrote. “He had been dead four days before I knew it. Realisation came to me slowly. I sat and stared at the slip of paper. Dead! I was never to see the light of his eyes again. I was never to hear that laugh of his. I had looked on my boy for the last time. Could it be true? Ah, I knew it was. And it was for this moment that I had been waiting, that we had all been waiting ever since we had sent John away to fight for his country. I think we had all felt that it must come. We had all known that it was too much to hope that he should be one of those to be spared. The black despair that had been hovering over me closed down now and enveloped all my senses. I felt that for me everything had come to an end. Everything had been swept away, erased…”

Lauder and his wife retreated behind closed doors at their family home in Strathaven, South Lanarkshire. Slowly, their faith in God brought them a form of “sad composure”. In a clear example of the vital role that religion and the idea of ‘heaven’ played for so many throughout this period, Lauder wrote that whilst there were moments when he asked ‘why’ it had to be his boy, “God came to me and slowly His peace entered my soul. He made me known that our boy had not been taken from us forever… my eyes will rest again upon his face. He will spy me and his voice will ring out as it used to do. ‘Hello Dad!’ he will call, and I will feel the grip of his young, strong arms about me.”

Despite repeated requests to return to the stage, Lauder’s grief understandably left him reluctant to make the most of his acclaimed ability to sing, entertain and make people laugh. He claimed that it was letters from other grieving parents, urging him to carry on for their sakes, that inspired his return.

Above: Keep Right On To The End of The Road was a hit that Harry Lauder wrote in memory of his fallen child. It was a message to all the bereaved who were suffering.

The eldest of seven children, Harry Lauder had been just 11 years of age when his father died, forcing him to take on work in an Edinburgh mill to support his mother and siblings and fund his own education. After winning a talent contest at the age of 13, he would go on to spend the next ten years perfecting his light comedy and singing act whilst working in a Glasgow coal mine.

The ‘big time’ finally beckoned after Lauder rebranded himself ‘the archetypal Scot’ – appearing in full Highland regalia, including a kilt, sporran, crooked walking stick and tam o’shanter. Lauder’s ability to write many of his own songs, such as hits like Roamin’ in the Gloamin’, were a massive career boost and, as a result, he was chosen to perform at the first ever Royal Gala show.

Lauder had come to fame at exactly the right time, courtesy of the birth of phonograph records and an international touring circuit. A massive ticket draw in both North America and Australia, by 1911 he had become the highest paid performer in the world and the first British artist to sell a million records. When available, his son John would often act as his piano accompanist.

At the outbreak of war, the Lauders were on tour in Australia. John returned immediately to enlist and his parents followed him home after Harry had fulfilled yet more concert dates in America. Back in Britain, the international star became a regular voice at recruitment campaigns and even paid out of his own pocket for a pipe and drum band to tour Britain and encourage enlistment.

When his son died, Harry Lauder did not lose faith in the war - if anything, he became even more outspoken about ‘shirking’. However, his real obsession became a need to see his son’s grave. In order to make this happen, less than 12 months after the death of his only child he gained permission to organise a concert tour that got close to the old frontlines. His book, ‘A Minstrel in France’, tells the remarkable story of this adventure, which even included being allowed to fire an artillery shell at the enemy from the newly-taken Vimy Ridge.

Above: Ovillers Military Cemetery (C) CWGC 2022 and the grave of Captain John Lauder. Photog

In an incredibly moving chapter about his feelings on reaching his son’s grave on the Somme, he wrote: “We set out across a field that had been ripped and torn by shell fire. All about us there were little brown mounds, each with a white wooden cross upon it. All over the valley was thickly sown with white crosses – and my own grief was altered by the vision of grief that had come to so many others. In the presence of so many evidences of grief and desolation, a private grief sank into its true perspective. It was no less keen, the agony at the thought of my boy was as sharp as ever, but I knew that I was only one father. God help us all.”

He added: “So we came, when we were perhaps half a mile from the Bapaume Road, to a slight eminence, a tiny hill that rose from the field. A little military cemetery crowned it. Here the graves were set in ordered rows, and there was a fence set around them, to keep them apart, and to mark that spot as holy ground until the end of time. Five hundred British boys lie sleeping in that small acre of silence, and among them is my own laddie. There the fondest hopes of my life, the hopes that sustained and cheered me through many years, lie buried.

“No one spoke. But the soldier pointed, silently and eloquently, to one brown mound in a row of brown mounds that looked alike. Then he drew away. And so I went alone to my boy's grave, and flung myself down upon the warm, friendly earth. My memories of that moment are not very clear, but I think that for a few minutes I was utterly spent, that my collapse was complete. He was such a good boy!”

Captain John Lauder is still to be found in that spot, at what is now known as Ovillers Military Cemetery. He was visited regularly after the war by his parents, and Harry Lauder would go onto write the famous post-war lament ‘Keep Right On ‘Till The End Of The Road’ in his memory - a song which resonated with bereaved parents and loved ones who, like he and his wife, were striving to exist with their pain and maintain sense of stoicism and duty.

Above: Harry Lauder with Winston Churchill at Strathaven.

Lauder would raise over a million pounds via a charitable fund he established for wounded men of the war and would continue performing until his death in 1950. In the Second World War he had offered his services to his nation once again and hosted Winston Churchill at his estate in Scotland.

Article by Dr Martin Purdy