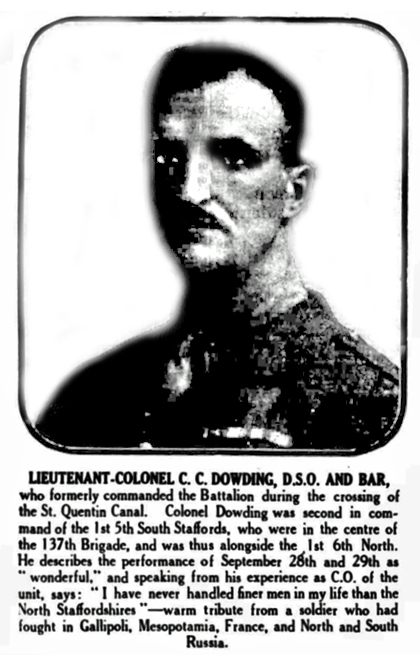

He fought on five fronts: The career of Charles Child Dowding DSO + Bar MC, CO 1/6th North Staffordshire Regiment TF (3 October 1918-Armistice)

- Home

- World War I Articles

- He fought on five fronts: The career of Charles Child Dowding DSO + Bar MC, CO 1/6th North Staffordshire Regiment TF (3 October 1918-Armistice)

Our disappearance down the rabbit hole of Charles Child Dowding’s military career began, as things often do in the West Midlands, with a query from the Wolverhampton WFA’s demon researcher, Richard Pursehouse, about whether we thought a photograph he had was that of Dowding. (We did.)

Above: The photo that kick-started the research project. In one of the most iconic photographs of 1918, or possible the entire war, we see Charles Dowding in the background as Brigadier General J V Campbell addresses troops of the 137th Brigade (46th Division) from the Riqueval Bridge over the St Quentin Canal. (IWM Q 9534)

Below: Same photo, slightly larger angle

We have a longstanding interest in the 46th (North Midland) Division TF, especially in the battalions of 137 (Staffordshire) Brigade. But our knowledge of Dowding was limited to the fact that he was the eighth and last commanding officer of the 1/6th North Staffords during the Great War. Our interest was piqued by a short newspaper article that outlined Dowding’s military career, in which he was described as having fought on five fronts.[1]

Above: The Burton Observer article dated 15 August 1940 which makes mention of him having served in five fronts.

For a man who was a civilian when the war broke out, this looked worthy of further investigation.

A Long and Winding Road

Documenting Charles Child Dowding’s military career has proved challenging. His army service file has not been released. The criteria for the release of officers’ services files in 1998 were that the officer had to have served in the British Army between 1914 and 1920 and left it by 31 March 1922. From what we knew of Dowding’s career, his file ought to have been released, but we eventually discovered that he had also served in the Second World War, which accounts for his file having been retained.[2] Nevertheless, we obtained from the Ministry of Defence a copy of Dowding’s Army Form [AF] B199a, ‘Personal details, Officers' Service’. And more recently, thanks to the good offices of Dowding’s grandson, Charlie, we received a copy of a short military memoir that Dowding started but did not complete. These additions clarified some things about his career, though confusions and contradictions remain.

Dowding gave two accounts of his entry into the British Army in 1914. The first was contained in a letter, written in 1921, to the Secretary, Board of Pensions, Commissioners for Canada, in support of his application for a Canadian War Gratuity. Dowding explained that he was farming at East Chilliwak, British Columbia, when the First World War broke out. He immediately applied to the GOC British Columbia, Brigadier-General Duff Stuart, for a commission. Stuart replied that he had no authority to issue commissions and advised Dowding to proceed to Ottawa. When he arrived in Ottawa he was informed by Sir Sam Hughes, the Canadian Minister for Militia and Defence, that all commissions in the Canadian First Contingent had been filled, but he could wait for future opportunities.

Above: Sam Hughes (in 1905)

His memoir, however, makes no mention of Stuart or Hughes or Ottawa but states that he was offered a commission by ‘Colonel Morrison’ at the Canadian Expeditionary Force training area at Valcartier Camp, Quebec.[3]

Above: Edward Whipple Bancroft (‘Dinky’) Morrison

Morrison’s offer was on the understanding that Dowding would remain in Canada to help with training. Where the two accounts agree is on Dowding’s impatient determination to get to the action as soon as possible and he immediately took ship for England.

Dowding’s accounts of his voyage to England are also contradictory and probably confused. In his 1921 letter he explained that he left Montreal on 3 September 1914 on board the SS Scotian, arriving in Liverpool on 11 September. In his memoir he describes boarding the ‘White Star Liner Scotian’ at Montreal on 30 August, arriving at Southampton in September.[4] The Scotian made its last voyage to Canada, from Liverpool, on 21 August 1914. On its final return voyage, it carried part of the Canadian First Contingent, which did not depart Canada until 3 October, arriving in Plymouth on 14 October. Either Dowding left for England on the Scotian later than he claimed or he did not travel on that ship, more probably the latter as his AF B199a states that he enlisted in King Edward’s Horse on 15 September 1914.

His route to a commission in the British Army was also convoluted, but the account given in his memoir appears to be the most accurate. Two days after arriving in England he joined 2nd King Edward’s Horse in London as a Trooper.[5] According to his AF B199a, he was promoted to Corporal on 31 October 1914 and ‘discharged to a commission’ on 29 December 1914. 2nd King Edward’s Horse was full of men worthy of commissions. Dowding states that c500 of the 750 men in the regiment were commissioned. After being commissioned on the General List, Dowding was one of five men from 2nd KEH who chose the Indian Army infantry.[6] They were sent to Cornwall for training with the 9th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. After a month, they were advised that all Indian infantry commissions had been filled from India and that if they wished to go to France they must transfer to the Indian Army cavalry. In November 1914 Dowding was sent to the 13th Reserve Cavalry Regiment at Colchester, but he was once again frustrated until, eventually, he ‘drifted’ into the 6th Battalion King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment.[7] And it was with the King’s Own that he entered his first Theatre of War, Gallipoli, on 13 June 1915.

Above: Dowding as a Lieutenant in 1914 wearing the cap badge of the General Service Corps.

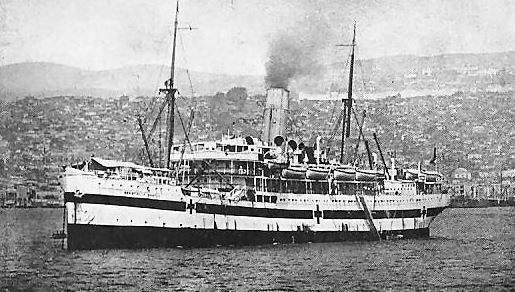

The 6th King’s Own was a K1 battalion, part of 38 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division, one of three New Army divisions sent to the Gallipoli peninsula to try and revive the flagging campaign in the summer of 1915. Dowding took part in the dismal routines of trench warfare on the peninsula, first as a platoon commander and later as a company commander. He was wounded by a bullet in his right thigh at Gully Beach on 14 July 1915 and was evacuated to Port Said on HMHS Grantully Castle, arriving on 17 July.

Above: HMHS Grantully Castle (image © Martin Edwards / www.roll-of-honour.com/Ships/HMHSGrantuallyCastle.htm)

He returned to the peninsula on 20 August 1915. Only a fragment of the 6th King’s Own War Diary has survived.[8] But from his AF B199a and from his own account, we know that shortly after his promotion to Captain and confirmation as OC “A” Company, he was informed by the GOC 38 Brigade, Brigadier-General G.W.C. Knatchbull, that he wanted Dowding as his Staff Captain.[9] It was in this capacity that he entered his second Theatre of War, Mesopotamia, disembarking at Basra on 27 February 1916.[10]

Above: Dowding's 'dog tag'.

His work as a Staff Captain brought him into close contact with 13th Division’s senior officers, including the new (from August 1915) divisional commander, Major-General Stanley Maude, a man for whom Dowding developed a great respect.

Above: Major-General Stanley Maude

The challenge facing 13th Division was to participate in the attempts to relieve Major-General C.V.F. Townshend’s army, which had been trapped in an insalubrious bend of the River Tigris at Kut-al-Amara since 7 December 1915, following its retreat from Ctesiphon. The Turkish defences were strong and were being constantly reinforced, both with troops and artillery. British assaults in January and March 1916 failed with heavy losses. A new commander, Major-General G.F. Gorringe, was appointed on 12 March. Gorringe’s attempted relief was launched on 5 April. This resulted in the capture of Hanna and Fallahiya, though at great cost. It was during the attempt of 9 April 1916 to take Sanniyat that Dowding suffered a gunshot wound to the face (centre lower jaw).[11] He had gone forward to reconnoitre the situation. The wound was severe, involving a broken jaw and penetration of his chest by a bullet which was eventually located close to his heart.[12] Serious wounds were usually treated either in India or back in Britain. Dowding was initially evacuated to Bombay, but the surgeons there were reluctant to operate, given the location of the bullet, so he was returned to England, entering Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital [QAMH], Millbank, London, on 4 June 1916, where he underwent an operation to remove the bullet (which he kept).[13]

Above: Dowding recuperating from the wound to his jaw.

His jaw was then painstakingly reconstructed by the King’s dental surgeon, Sir Francis Farmer.[14] Dowding was awarded the Military Cross on 24 June for his actions at Kut ‘in rallying a large number of men who had fallen back and leading them forward to the assault until he was severely wounded’[15] and mentioned in despatches on 13 July 1916.[16]

Above: Dowding with his MC ribbon (he was told of the award in June 1916), with General Staff collar tabs and Cap badge. He was Staff when he was wounded in Mesopotamia in April 1916, and ceased to be Staff on his departure for France in April 1917. So this photo was taken between June 1916 and April 1917. In June he was having significant treatment for his jaw injuries. This photo shows those wounds have healed completely, it is thought that the photo was taken in September 1916 at the earliest, possibly later.

Dowding’s recuperation was a lengthy one. He did not return to active service until April 1917, a year after his wounding, spending some of the time on light duties at Plymouth. Officers and men who were evacuated to Britain from the middle-eastern theatres were rarely returned there. This was the case with Dowding, whose next Theatre of War would be the Western Front. On 15 April 1917 he reported for duty with the 11th Battalion King’s Own.[17] He was posted to “A” Company. 11th King’s Own had been formed as a Bantam battalion in August 1915 and became part of 120 Brigade (Brigadier-General Hon. C.S. Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby), 40th Division (Major-General H.G. Ruggles-Brise).

Above: Major-General H.G. Ruggles-Brise

The ‘bantam experiment’ had quickly unravelled.[18] A large number of unfit men, especially in 120 and 121 Brigades, had to be weeded out. This necessitated considerable reinforcement and reorganization before the division could be deployed.[19] By the time Dowding joined the division it had long shed its ‘bantam’ identity.

In May 1917 Dowding was asked by Brigadier-General John Campbell (GOC 121 Brigade) if he would take over as 2 i/c of 13th Battalion East Surrey Regiment, with the rank of Acting Major, but the night after his arrival he went down with trench fever, necessitating a return to hospital in England. On 21 June 1917 Dowding was to be found acting as a Judge at the Canadian Training School Sports Field Day in Egerton Park, Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex.[20] By 9 July 1917 he had returned to the front, where he was attached as 2 i/c to 18th (Service) Battalion Welsh Regiment (2nd Glamorgan), which was also a unit in 40th Division, but in 119 Brigade, commanded by the infamous Frank Crozier.[21]

Above: Frank Crozier

The CO 18th Welsh, Lieutenant-Colonel J.R. Heelis, had reported sick and his 2 i/c, Major William Kennedy, had taken over the battalion. Hence the need for a new 2 i/c. Dowding greatly admired Kennedy, the son of a Lanarkshire textile manufacturer and a brilliant academic economist, an unlikely but undoubted warrior. Kennedy was killed at Cambrai on 23 November 1917, aged only 32. Dowding was again home on leave between 5 and 20 September 1917, but he was with 18th Welsh for 119 Brigade’s finest moment in the war, its role in the capture of Bourlon Wood during the battle of Cambrai.[22] He was again wounded (gunshot wound to the left leg and shoulder), on 23 November.[23]

He found himself back in Britain, this time at the 3rd London General Hospital, Wandsworth Common. He was not discharged until 22 January 1918.[24]

Above: Third London General Hospital, Wandsworth

Dowding was mentioned in despatches in the London Gazette on 24 May 1918.[25] His DSO was gazetted on 3 June 1918.[26] He received a further mention in despatches on 9 July 1918. The London Gazette described him as ‘T/Major C.C. Dowding DSO MC, 18th Btn Welsh Regiment, attd. 5th North Staffords’. On the same date, the Nairnshire Telegraph report of his DSO described him as ‘King’s Own Royal Lancs, attd 9th Welsh Regiment’.

Above: Charles Child Dowding DSO*, MC

The 5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment was a composite unit formed from the 1/5th Battalion TF and the 2/5thBattalion TF on 6 February 1918. It suffered heavily as part of 176 Brigade, 59th (2nd North Midland) Division TF during the German Spring Offensives. As a result, it was disbanded and reduced to training cadre in 16th (Irish) Division on 9 May 1918.[27] It transferred to 34th Division on 17 June 1918 and then to 117 Brigade, 39th Division (27 June 1918) and finally to 116 Brigade, 39th Division (12 August 1918). The battalion War Diary covering the period February-May 1918 (TNA: WO95/3021) was well kept, especially regarding movements of officers in and out of the battalion. There is no mention of Dowding. The War Diary covering the period August-November 1918 (TNA: WO95/2583) is less detailed, but again has no mention of Dowding. Even so, he is shown in the comprehensive list of officers and men who served with the 1/5th and 5th North Staffords compiled by Janice and Levison Wood and is listed in Walter Meakin’s battalion history, published in 1920.

There are no references to Dowding in the 9th Battalion Welsh Regiment War Diary either, but his AF B103 Casualty Form-Active Service, shows him posted to the 9th Welsh Regiment on 6 May 1918. This unit was in 58 Brigade, 19th (Western) Division.

On 9 September 1918 Dowding was posted to the 1/5th Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment, 137 Brigade (Brigadier-General J.V. Campbell VC), 46th Division TF (Major-General G.F. Boyd), taking over the duties of second in command and care of the War Diary.[28] He was in this post during the great attack at Bellenglise on 29 September 1918. Four days later he took command of the 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment following the death in action of Lieutenant-Colonel T.R. Evans.[29] He was thirty-three years old.

Although it is commonly stated that the 46th Division ‘broke the Hindenburg Line’ on 29 September 1918, it really only broke in to the system. There was much hard fighting to follow in the days and weeks ahead. Dowding took over command of the 1/6th North Staffords at a moment of crisis. This is reflected in the citation to his second DSO, earned on his first day as CO: ‘Near Sequehart, for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during the operations of 3rd October 1918, in the attack at Mannequin Hill. He showed great coolness and power of leadership. Whilst in command of the 1/6th Bn., North Staffordshire Regiment, he handled a difficult situation with great skill under heavy shell and machine gun fire.’[30] This command, during some of the heaviest and most successful fighting in the history of the British Army, concluded his service on the Western Front.[31]

It may be worthwhile summarising Dowding’s career to this point: by November 1918 he had served in five (possibly seven) regiments, including two battalions of the King’s Own, two battalions of the Welsh Regiment, two battalions of the North Staffordshire Regiment and a battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment, in three Theatres of War.[32] He had been wounded four times. This would seem like enough soldiering for one lifetime, but there was more to come.

The start of 1919 saw Dowding once more in hospital. He was admitted to QAMH from a sick convoy on 31 January 1919 with a fractured right clavicle. The hospital register suggests that the fracture was the result of an accident.[33] It must have been a bad accident. He was under treatment for forty-eight days and was not discharged to duty until 13 March 1919. A bar to his DSO had been gazetted on 4 March 1919.[34] This was surely the time to say ‘goodbye to all that’ and settle down to married life. Dowding had married a nurse, Nita Mackay Ross (1889-1929), the daughter of a Scottish lawyer, at the church of Frimley St Peter, Surrey, on 19 January 1917.[35]

Above: Nita Mackay Ross (1889-1929)

Their first child, John Charles Lovell Dowding (1917-1982), was born on 27 November 1917.[36] His wife was pregnant with their second child, Evelyn Marie (‘Bunny’) Dowding (1919-96), at the time of Dowding’s release from hospital. This did not prevent his volunteering for service with the Russian Expeditionary Force, which was being assembled to try and roll back the tide of Bolshevism. He sailed from South Shields for North Russia on 27 May 1919.[37]

It is a familiar trope among authors and, especially, publishers, to describe some historical event as ‘forgotten’. This is true of Allied intervention in the Russian civil war, though ‘wilfully ignored’ might be more appropriate than ‘forgotten’. This is despite an extensive scholarly literature.[38] Intervention began before the defeat of Germany and was a multi-national affair, involving the British Empire, France, Italy, the United States, Japan, Greece, Serbia, Poland, Romania and Czechoslovakia. British military forces were deployed to North Russia (Archangel and Murmansk) (1918-19), Siberia (Vladivostok) (1918-22), the Baltic States (1918-19) and the Caucasus (1917-19). The initial motivation was to prevent war material falling into the hands of Germany after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) took Russia out of the war and to rescue forces that had become trapped in Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution, especially the Czech Legion, in effect to re-establish the Eastern Front. This motive was later reinforced by a desire to help the Russian opponents of Bolshevism (the Whites), who had remained faithful to the Allied cause, and to counteract what was increasingly seen as the wider Communist threat to Western Europe.

Charles Dowding joined the North Russia Relief Force. This was a volunteer formation that had begun recruiting in April 1919 and whose purpose was to protect existing British positions established in the last four months of 1918. The intervention was marked by heavy fighting, increasing disaffection with the divided and unreliable Whites and several mutinies, not only of White troops but also of Allied ones, including British. By the autumn of 1919 the intervention had run its course and troops were evacuated from Archangel in September and Murmansk in October.[39] The intervention had become extremely unpopular at home. The British people were tired of war and had no appetite for sending British conscripts to fight in Russia. Dowding was not an admirer of the Force’s commanding officer, Brigadier-General (later Field-Marshal Sir) W.E. (‘Tiny’) Ironside, whom he scathingly dismissed as ‘one of the most foolish Generals the War had produced’.[40]

Above: Ironside in Iran in 1920

According to Dowding’s AF B199a, he took command of the ‘Bolshi [Bolshie] Ogerka [Ozerki] Column, Archangel’ in September 1919. Bolshie Ozerki was a small village on the important Archangel-Vologoda railway. There was a significant battle that began there on 31 March 1919 and lasted until 5 April. Allied losses were heavier than those of the Red Army and the village remained under Red Army control American casualties played a significant part in President Wilson’s decision to withdraw US troops from Russia. Dowding did not arrive in Russia until after these events. It is not clear what his ‘command’ of the Bolshie-Ozerki Column involved, but in February 1920 he received another mention in despatches, ‘For valuable and distinguished services rendered in connection with the operations in North Russia during the period 25 March to 26 September 1919’.[41] Dowding officially ceased to be employed as a British officer on 23 October 1919.[42] But even this did not bring his military career to an end.

In September 1919 Dowding’s former brigade commander in 40th Division, Frank Crozier, had accepted the post of Inspector-General of the military forces of the newly independent republic of Lithuania fighting to establish itself. Crozier began putting his ‘team’ together by recruiting men who had served with him on the Western Front.[43] To these, he added men who had not only served with him in France but had also been in Russia. One of these was Charles Dowding.[44] It is not clear when Dowding arrived in Lithuania, but it must have been after he ceased being a British officer. Although Dowding’s AF B199a gives the impression that Crozier’s mission was an official British operation, it was not. Crozier accepted the post of Lithuanian Inspector-General after his efforts to obtain a Regular commission in the British Army failed. Bertram Cubitt, the Under-Secretary of State for War, emphasised that ‘General Crozier proceeded to Lithuania in a purely private capacity and has severed his connection with His Majesty's Forces’.[45] Dowding’s appointment as ‘Staff Colonel with Mission to Kovno, Lithuania’ in December 1919, listed in his AF B199a, was therefore not a British appointment and it is unclear who appointed him.[46] Dowding evidently appreciated his time in Lithuania, describing it as a ‘wonderful little country’.[47] Crozier, however, considered the whole enterprise to be a ‘ghastly mistake’. Some of his choices as officers were poor ones and the rapacity and licentiousness of some of them played a part in the termination of his mission on 1 March 1920. Dowding had left on 12 January.[48] This really did mark the end (well, until the Second World War, anyway). He returned to Canada with his wife and children in May.

Suitable Young Men

The British Army issued 229,316 commissions during the First World War, but only 16,544 of these were permanent commissions in the Regular Army. The rapid, massive and totally unexpected expansion of the British Army in the aftermath of Lord Kitchener’s appointment as Secretary of State for War in August 1914 created an ‘officer problem’, exacerbated by high officer casualties in the BEF. It took many months before the army was able to establish a satisfactory system for the selection and training of junior temporary officers with the establishment of Officer Cadet Battalions [OCBs] in February 1916.[49] The OCBs were ultimately responsible for commissioning 145,621 men, but more than 70,000 commissions were granted before this system was established, overwhelmingly in 1914 and 1915.[50] The need to find junior officers was urgent and compelling. ‘To obtain the supply at once and in sufficient numbers,’ wrote Keith Simpson, ‘it was necessary to waive the preliminary training, either at a military college or in the ranks, which was required for officers holding permanent commissions. Instead, it was decided to offer temporary rather than permanent commissions in the regular army to suitable young men.’[51] Charles Child Dowding was one of these officers.

Above: A 'typical' OTC group: Men of the 20th Officer Cadet Battalion, shown in December 1917

Why did the army think Dowding was a ‘suitable young man’? There is little doubt that British officer selection in the early days of the war was heavily influenced by social considerations, in which a public school education and a professional occupation were at the forefront. These, together with some experience in the Officers Training Corps [OTC] and a sporting background, especially in Rugby Union, were widely believed to ensure that men had ‘the right stuff’.[52] What we know of Charles Dowding’s life before he emigrated to Canada in 1909, aged 24, does not conform to the social stereotypes of officer suitability current at the time.

Dowding did not come from a privileged background. He was born on 23 March 1885, at Shepton Montague, Somerset, the fifth of seven children (and second son) of Charles Dowding (1847-1917) and Martha Clulow Child (1853-1951). Dowding was the son and grandson of farmers; his mother was the daughter of a farmer. In the 1861 Census, his grandfather, Thomas Dowding (1814-75), was recorded as farming 200 acres at Shepton Montague, employing seven men and three boys; by 1871 he was farming 170 acres, employing six men and two boys. Charles Dowding Snr evidently took over the farm after his father’s death. In the 1881 Census he was recorded as farming 177 acres, employing five labourers and two boys. This all looks very respectable. Indeed, in the baptismal register of the parish of Shepton Montague, 14 April 1885, Charles Dowding’s father is described as a ‘yeoman’, a very English term redolent of loyalty, steadfastness and courage. Yeomen were usually characterised as landowners, albeit small ones. If Charles Dowding Snr was a yeoman in this sense of the word, it was a status he failed to maintain. His frequent moves - from Shepton Montague, to North Cheriton, to South Cheriton and to James Farm, at Winsor, near Totton, in Hampshire - suggest that he was a tenant farmer, not a landowner.[53]

The private life of Charles Dowding Snr was also far from straight forward. His wife left him in 1890 and went to live in Wimbledon. On 31 October 1890 she petitioned the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court of Justice for a divorce on the grounds of cruelty. The Petition does not make comfortable reading.[54] Despite the evidence that Mrs Dowding offered, the Petition appears not to have been granted or was withdrawn. Perhaps the occasion brought Dowding to his senses. He and Martha were still living together in 1891, 1901 and 1911, by which time the family had given up farming and was keeping a boarding house at the seaside resort of Cromer, in Norfolk.[55]

Charles Child Dowding appears not to have had an education beyond elementary school level. He is to be found in the registers of St Faith’s Church of England (Aided) School, Winchester, in 1894, aged nine, together with his older brother Henry and his sister Norah,[56] and Bracon Ash School, near Norwich, in 1896, aged eleven, together with his sisters Norah, Lily and Violet.[57]

On 2 January 1901 Dowding joined the Militia Battalion of the Prince of Wales’s Own Norfolk Artillery. He stated his age as eighteen, though in fact he would not be sixteen until 23 March 1901.[58] His occupation was ‘stableman’. He enlisted in the Royal Artillery, Regular Army, on 4 March 1901 and ‘joined for service’ three days later. He stayed in the army until 3 March 1913, including three years’ service in India, when he was discharged ‘on termination of engagement’.[59] By then, he was farming in Canada.

What of Charles Child Dowding’s siblings? His elder brother, Henry Charles (1883-1913), preceded him into the army. He joined the Militia Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment, aged 18 years and 6 months, on 4 February 1899, stating his civilian occupation as ‘carter’. A few weeks later, on 20 April 1899, he joined the Royal Artillery [RA], stating his civilian occupation as ‘seaman’. He became a career soldier in the RA, much of his service being spent in India. He twice extended his terms of service, first to eight years and then to twelve. On 6 June 1910 he re-engaged a third time. This would have taken his service to 21 years. He was promoted Saddler Corporal on 16 October 1912, but died of enteric [typhoid] fever at Rawalpindi on 23 September 1913, aged 40, leaving a widow and the not insubstantial sum for an NCO of £220 4s 0d.

Two of Dowding’s sisters, Winifred Kate (1880-1926) and Caroline Margaret (‘Carrie’) (1882-1949), were involved in the boarding house business.[60] Norah (1887-1977) trained at the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital between 1906 and 1909 and then became a private nurse. In the 1911 Census she was recorded as working for Sir Reginald W. Proctor-Beauchamp Bt. (1853-1912), of Langley Park, Norfolk.[61] On 26 June 1916 Norah joined Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service [QAIMNS] as a Staff Nurse. She served until August 1919, when her resignation was accepted on the grounds of her forthcoming marriage. She did not, in fact, marry until 20 September 1922. Her husband was William Richard Mack (1870-1956), a farmer eighteen years her senior.[62] Lilian Ada (1888-1983) also married a local farmer, Charles Newdick (1876-1972), in 1912. Dowding’s youngest sibling, Violet Evelyn (1890-1908), died on 20 February 1908 from tuberculosis, aged eighteen.

Had Dowding still been living in England in 1914, it is difficult to imagine his being commissioned. With a family in the boarding house business, with no evidence of education beyond elementary school, whose only military career was as a Gunner in the Royal Artillery, he does not look like obvious officer material. What probably clinched his commissioning was his emigration to Canada. This put him outside British social structures and conventions. He was not a ‘callow schoolboy’. He was twenty-nine when he was commissioned. Judging by his photographs, he was tall,[63] robust and tough-looking. He presented as a hardy, independent, self-reliant, frontiersman, with a track record of being able to manage men.[64] Dowding’s military career certainly justified his commissioning.

A Son of Empire

Dowding was far from alone in emigrating to Canada before the First World War. 1900-13 were the peak years of British emigration, with 3.15M emigrants. The Canadian government pursued an aggressive immigration policy that favoured people willing to work in agriculture, seen as vital to the development of the Western provinces. Assisted passages were sometimes available, but even if they were not a steerage fare on an emigrant ship could be obtained for sums in the region of £5. It is possible that Charles Dowding felt the attractions of Canada and made his way there under his own steam. But it is also possible that his emigration to Canada was facilitated by the Naval & Military Emigration League, which lobbied to involve the Canadian and British governments in the migration of British ex-servicemen.[65] By his own account Dowding left for Canada in 1909, but the Canadian Census of 1911 listed his arrival there as ‘1910’. He was employed as a farm foreman to a tenant farmer, Louis Scott-Elliot, who held the land from the Hatzic Prairie Land Company. Dowding was then based near Vancouver, some fifty miles west of East Chilliwak, where he was farming in August 1914. This suggests he had come up in the world and was working for himself.[66]

Dowding’s return to civilian life was not smooth. Although he returned to East Chilliwak, it was not to the land he was farming in 1914. He had lost this as a result of his being away at war. He took up a new property under the Soldier Settlement Board. This had been established in 1917 to assist returned servicemen in setting up farms. People who farmed under these arrangements were subject to regular inspection. Dowding’s stewardship must have been satisfactory as he was still farming a decade later. In the early days Dowding found himself short of money. He applied for, and in 1921 eventually received, a Canadian War Service Gratuity, but only after deduction of the monies he had received from the ‘Imperial Authorities’. He was informed that the Canadian government made no provision for the payment of Separation Allowance for services performed in the Imperial Forces. He was also informed, correctly, that Separation Allowance was not paid on account of officers’ dependents by the Imperial Authorities. Welcome home!

The direction of Dowding’s life changed dramatically after the death of his wife, Nita, from pneumonia on 8 January 1929, aged 39. On 16 February 1929 he returned to Britain with his children and stayed with his mother in Cromer. He remained in England until October, when he took ship from Southampton to Quebec, but without his children. A year later, in October 1930, his engagement was announced to Mrs Alice Jamieson (née Reynolds) (1874-1965), a widow whose family-owned extensive sheep farms in New Zealand.[67] According to family legend, the couple met on the first tee of the Chilliwak Golf Club.[68] Beginning in May 1930 Mrs Jamieson made a series of holiday cruises that took her several times to Vancouver, via Auckland, Suva and Honolulu. Dowding appears not to have been to New Zealand until his wedding. The engagement announcement in the Poverty Bay Herald describes Dowding as ‘of Chilliwak, British Columbia’.[69] He arrived in Auckland from Vancouver on 30 November 1930 and married Alice in Gisborne on 9 December.[70]

Dowding’s life seemed destined never to be ordinary. On 3 March 1931 he and his wife were badly injured in an earthquake at Hawke’s Bay.[71] They took ship for England in May in order to help their recuperation. They remained in England until 30 October, when they departed Southampton for Wellington, arriving on 12 December. There was no sign of Charles’s children until 30 September 1933 when he, Alice, John and Evelyn sailed from Liverpool to Auckland, First Class, arriving on 9 November.[72] He and Alice made further trips to Britain in 1936 and 1939. The latter trip began the last chapter of Charles’s military career.

Above: Charles and Alice - this photo was taken at the wedding of his son (by his first marriage), in 1946.

In July 1939 Dowding visited the War Office in London and offered his services in ‘any capacity’ only to be told that there would be no war, but he was asked to call again before he returned to New Zealand.[73] He did so in September after the war had begun. This time his offer was accepted. He was given an Emergency Regular Officer Commission on the General List as a Lieutenant on 19 December 1939 and appointed acting Lieutenant-Colonel the same day. He reported to No. 1 AMPC [Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps] Training Centre, Hythe, on 20 December to take command of an Auxiliary Pioneer Battalion.[74] He was fifty-four years old. His battalion was a new unit. At the start of September 1939, Works Labour Companies had been formed from Reservists. These were soon grouped together into the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps. After undertaking training in England, the battalion arrived in France on 30 March 1940 as part of III Corps. Prior to this, on 13 March, Dowding had been made Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel and War Substantive Major.

Above: Dowding in the Second World War. He is seated second from the right and is looking slightly away from the camera

Dowding gave an account of the events of 1940 in a talk to the Gisborne Rotary Club after his return to New Zealand in 1943. This was reported in the Opotiki News.[75] The Auxiliary Pioneer Battalions were intended to be combat units, though according to Dowding no one had thought to give them the tools necessary to engage effectively in combat. He explained that ‘equipment and ammunition were very short’. The thousand pioneers under his command had ‘only twenty-five rifles to every 100 men and no machine guns or anti-tank guns’. When the German attack began on 9 May 1940, Dowding was left behind as rear area commandant, but ‘the break-through occurred before they could settle down to their work’. Dowding eventually found himself in the small town of Berques, four miles from Dunkirk. ‘The defences were held by 2000 men, mainly pioneers, with only three machine guns and three anti-tank guns, but no anti-aircraft guns, but these men put up a marvellous show.’ The defenders were eventually relieved by the British 48th Division and after them the French.

Above: Dunkirk, 1940

Dowding was admiring of British fighting spirit but highly critical of the French, especially their senior commanders. He eventually got away in what he believed was ‘the last destroyer to scrape through the wrecked lock gates’ in Dunkirk harbour.[76]

Dowding’s evacuation, the third of his military career, following Gallipoli and Archangel, ended his time as a combat soldier, but not his military service. On 5 June 1940 he was appointed Assistant Director of Labour, at HQ Northern Command, York. His post was upgraded to that of Deputy Director of Labour, with the rank of Colonel, on 26 November 1940. He appears to have held this post until he relinquished his commission on 21 December 1943 and was granted the honorary rank of Colonel. He returned to New Zealand, where he died on 13 May 1961, aged 75. The surprising thing is that nothing dramatic appears to have happened to him during the last seventeen years of his life!

Above: Dowding's grave at Taruheru Cemetery, Gisborne, New Zealand

There are few human activities more demanding than military command in war. The challenge is to retain the power of decision amid confusion, fear and the demands and expectations of others. Throughout his life Dowding displayed a capacity to make bold, life-changing decisions: joining the army aged fifteen; emigrating to Canada aged twenty-four; instantly resolving to join up on the outbreak of war and sailing for England as soon as his prospects in Canada were frustrated; marrying his second wife after a very brief acquaintance and relocating to New Zealand; immediately offering his services on the outbreak of the Second World War. It was this quality that recommended him as a ‘go to man’ during the Great War, someone who could be slotted into a battalion in an emergency and make a positive difference, which is what he did.

Article submitted by

J.M. Bourne and Andy Johnson

[The authors are delighted to acknowledge the help of Nick Baker, Janice Bovill (Army Personnel Centre, Ministry of Defence), Jeff Elson, Emma Goodrum (Archivist and Records Manager, Worcester College, Oxford), Dr Alison Hine, Mick Rowson, William Spencer, Dr Mike Taylor and Janice and Levison Wood in researching this article. Particular thanks are owed to members of the Dowding family, especially Charles Dowding’s grandson, Charlie Dowding, and a more distant relative, Philip Dowding.]

Appendix 1

Charles Child Dowding’s Predecessors as Commanding Officers of the 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment TF1914-18

Dowding had seven predecessors. The first three men to command the battalion (Ratcliff, Gretton and Boote) were Territorials and North Staffords. After the death in action of Colonel Boote in July 1916 the Territorial connection was broken. Of the next four COs, two (Odling and Stoney) were Regulars and two (Douglas and Evans, like Dowding) were civilians when the war broke out. Five of the seven attended public school (Odling probably did as well and Evans definitely didn’t) and two (Ratcliff and Evans) were graduates. Four were businessmen and one (Evans) was a civil servant. Ratcliff and Gretton were brewers, Boote was a tile manufacturer and Douglas a timber importer. Ratcliff and Gretton were wealthy men and Members of Parliament. The seven included two Olympic champions (Gretton and Douglas). Douglas was also captain of the England cricket team, before and after the war. Two of the seven (Boote and Evans) were killed in action and one (Stoney) wounded. All battalions were unique, but the 1/6th North Staffords broadly follows the trend of the war in TF battalions, from older to younger men in command, from Territorials to non-Territorials, from the socially and politically well-connected to young Regulars and civilians from varied backgrounds, some of them modest.

Biographies

Ratcliff, Robert Frederick CMG (1867-1943)

CO: 18 November 1909-25 October 1914 (82 days from 4 August 1914); 20 May 1915-14 May 1916 (360 days). Aged 42 on appointment in 1909; aged 47 in August 1914. Not employed again as a CO after May 1916.

Military Status in August 1914: Lieutenant-Colonel TF; served in the South African War, 1901

Family: b. 15 April 1867 at Stapenhill DRB, son of Robert Ratcliff (1836-1912), brewer, landowner and farmer, and Emily Payne (1837-1916); unmarried; d. 19 January 1943 at The Park Hotel, Derby, aged 75.

Education: Rossall School and Jesus College, Cambridge (BA, 1889)

Other: MP Burton-on-Trent, 1900-18; Director, Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton, brewers

Honours and Awards: JP Staffordshire; High Sheriff, Derbyshire.

Probate: £844,527 0s 4d

Above: Robert Ratcliff (National Portrait Gallery)

Gretton, John (1867-1947)

CO: 25 October 1914-20 May 1915 (207 days). Aged 47 on appointment. Not employed again as a CO after May 1915.

Military Status in August 1914: Hon. Lieutenant-Colonel North Staffordshire Regiment TF Reserve. He was an officer in the 2nd Volunteer Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, but continued into the TF on its formation in 1908. He ended his military service as Lieutenant-Colonel Territorial Force Reserve in 1922, when he was demobilised, aged 55.

Personal: b. 1 September 1867 at Winshill STF, son of John Gretton, Stapleford Park (1836-99), brewer, malster, landowner and farmer, and Marianne Louisa Molineux (1846-91); m. Hon. Maud Helen Evelyn de Moleyns (1870-1934), daughter of 4th Baron Ventry (1828-1914); 2s 3d; d. 2 June 1947 at Melton Mowbray LEI, aged 79.

Education: Harrow School

Other: MP Derbyshire South, 1895-1906; MP Rutland, 1907-18; MP Burton-on-Trent, 1918-43. Chairman, Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton, brewers, 1908-45. He won two gold medals in yachting at the 1900 Olympics and played a leading role in bringing down the Lloyd George Coalition government in 1922.

Honours and Awards: Baron (1944); PC (1926); CBE (1919); VD; TD; Deputy Lieutenant of Derbyshire.

Service File: TNA: WO 374/29282.

Probate: £2,302,972 12s 6d

Above: John Gretton (National Portrait Gallery)

Boote, Charles Edmund (1875-1916)

CO: 15 May 1916-1 July 1916 (77 days). Aged 41 on appointment. Killed in action, 1 July 1916, at Gommecourt.

Military Status in August 1914: Major, 5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment TF. He was an officer in the 2nd Volunteer Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, but continued into the TF on its formation in 1908. Served in South Africa, 1900-1.

Personal: b. June (or July) 1874 at Norton Bridge STF, son of Richard Boote (1823-1891), potter (founder [1842] of T&R Boote of Burslem), and Sarah Anne Boote (c.1835-1907), Shallowford STF; m. Gertrude Ethel Laybourn (1873-1954) (m. 7 April 1896); 2d 1s; kia, 1 July 1916, aged 41. He is buried in Gommecourt Wood New Cemetery, Foncquevillers, France.

Education: Shrewsbury School

Other: Director, T.& R. Boote, Burslem, tile manufacturers

Honours and Awards: VM; TD; JP Stoke-on-Trent

Service File: TNA WO 374/7607

Probate: £9,241 9s 6d

Above: Charles Boote (www.stwilfrid.org/ww1-memoriam)

Odling, William Alfred (1879-1943)

CO: 13 July 1916-30 January 1917 (174 days). Aged 37 on appointment. Replaced and not used again as a CO. He briefly and temporarily commanded 137 Brigade, 9-17 November 1916.

Military Status in August 1914: Professional soldier, Captain, Middlesex Regiment, Regular Army, commissioned 23 May 1900; Adjutant, 3rd Battalion Middlesex Regiment, 26 July 1911-6 December 1915; retired in the rank of Major, 1919.Odlingstarted to read medicine at Worcester College, Oxford, in October 1897 and was seemingly headed for the medical profession, like his father. This changed when he was recommended by the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University for a commission in the army during the South African War.[77]

Personal: b. 14 January 1879, at Oxford, 2nd son of William Odling FRS (1829-1921), physician, Waynfleete Professor of Chemistry, Oxford University, and Elizabeth Mary Smee (1843-1919); m. Mary Bennett Case (1880-1963) (m. 8 September 1908), daughter of the President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford; 2s; d. at Paxford House, Paxford GLO on 14 January 1943, his sixty-fourth birthday.

Education: Worcester College, Oxford

Probate: £13,356 3s 9d

Douglas, John William Henry Tyler ('Johnny') (1882-1930)

CO: 19 January 1917-11 March 1917(51 days). Aged 34 on appointment. Afterwards CO 20th (Service) Battalion King’s (Liverpool Regiment) (4th City), 11 March 1917-1 February 1918 (327 days); later served on the staff.

Military Status in August 1914: Civilian (timber importer); commissioned in the Special Reserve of the Bedfordshire Regiment, 22 September 1914; joined 1/6th North Staffords, 14 January 1917.

Personal: b. 3 September 1882 at Stoke Newington MDX, son of John Herbert Douglas (1853–1930), timber importer, and Julia Ann Tyler; m. Evelyn Ruby Case (née Ferguson) (m. 25 Dec 1916), widow of Captain Thomas Elphinstone Case, Coldstream Guards, 1 stepson, the actor Gerald Case (1905-85); d. at sea on 19 December 1930 in the sinking of the Finnish passenger ship, SS Oberon, aged 48. His father also died in the sinking.

Education: Moulton Grammar School and Felsted School

Other: Essex (1901-28) and England Cricket Captain (1911-12; 1913-14; 1920-21); ABA Middleweight Champion (1905), Olympic Champion (1908).

Service File: TNA WO 339/27222

Probate: £27,752 12s 4d

Above: John Douglas

Stoney, Henry Howard DSO (1886-1955)

CO: 11 March 1917-1 September 1918, when wounded (539 days). Aged 30 on appointment. He previously commanded 1/5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, 9 August 1916 - 9 December 1916, when he was wounded. He was the longest serving of the battalion’s commanders during the war. He remained in the army after the war: Adjutant, 5th North Staffords, 1923-26; 2 i/c 5th North Staffords, 1926-29; CO 5th North Staffords, 1929-33; OC 137 (Staffordshire) Brigade, 1934-37.

Military Status in August 1914: Professional soldier: Lieutenant, 2nd Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, Regular Army, commissioned 16 August 1905. Saw active service on the NWF (Tochi Valley operations), 28 November 1914-27 March 1915; Mohmand Expedition, September and October 1915. Invalided back to Britain after an accident playing polo in India.

Personal: b. 12 March 1886, at Meerut, India, son of Major George Ormond Stoney (1846-90), King’s Own Scottish Borderers, and Meylia Margery Jessie Chalmers (1848-1910); m. Laura Kathleen Stoney (1893-1970) (m. 12 June 1917); 1s1d; d. 27 February 1955 at Okefield Stable Cottage, Lyndhurst HMP, aged 68. His brother, Lieutenant-Colonel George Butler Stoney (1877-1915), CO 1st Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers, KiA Gallipoli, 15 October 1915. The Stoneys were a prominent Irish family.

Education: Wellington College and RMC Sandhurst

Honours and Awards: DSO (LG1 January 1918)

Other: Pig and poultry farmer after leaving the army

Probate: £5,190 12s 8d

Evans, Thomas Richard DSO (1884-1918)

CO: 1 September 1918-3 October 1918 (32 days). Aged 34 on appointment. It fell to Evans to command the 1/6th North Staffords on their greatest day, the crossing of the St Quentin Canal at Bellenglise, on 29 September 1918. He was killed in action four days later during the attack on Ramicourt.

Military Status in August 1914: Civilian (Civil Servant Customs & Excise); commissioned in the 15th(Service) Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers(London Welsh) on 29 October 1914; promoted T/Captain 7 December 1914; seconded to 20th (Reserve) Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers at Kinmel Park, near Colwyn Bay, eventually as T/Major and 2 i/c. He was sent out to the 17th (Service) Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers (2nd North Wales) in August 1916 and made OC “A” Coy. After only five weeks, he was made 2 i/c of a Senior Officers’ School and then Commandant of a Junior Officers’ School. T/CO 17th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 20-28 December 1917. He was attached to the 1/6th North Staffords on 28 December 1917 and took command of the battalion on 1 September 1918, following the wounding of Colonel Stoney.

Personal: b. 27 January 1884 at Llanwyddn MTG, son of Hugh Evans (1855-1932), stone cutter, and Mary Evans (1864-98); m. Hirell Catherine Douglas Young (1888-1981) (m. 1907); 1d 1s; killed in action, 3 October 1918, aged 34. He is buried in Bellicourt British Cemetery, France.

Education: Birkbeck College, London University (BA, 1916)[78]

Other: Evans’s military career is astonishing considering his origins. He was the oldest of six children born to the first wife of a Welsh stone cutter.[79] When the war broke out he was a thirty-year old minor civil servant, with an estranged wife and two small children, literary inclinations and a thirst for self-improvement.[80] He moved in artistic circles in London and knew many well-known journalists and writers. He was bilingual and wrote poetry and plays in Welsh. His pre-war military experience was confined to membership of the London University OTC. None of this screams ‘warrior’, but that is what he was (or became).

Honours and Awards: DSO (LG 8 March 1919)

Service File: TNA WO 339/29144.

Probate: £260 8s 8d.

Above: Thomas Evans (IWM Lives of the First World War)

Appendix 2

Dowding’s Wounds and Medical Treatment

In his unfinished memoir Dowding gave details of his wounds and medical treatment. His accounts are below, with a commentary in italics by retired surgeon Ronald Cullen MB ChB FRCS of the Wolverhampton WFA.

Gallipoli

Memoir: ‘Two days later found us digging in on the cliff face. We must have made a good target, for very quickly the guns from Achi Baba had opened on us with shrapnel & on July 14th I collected one through the right thigh. This must have rested on a nerve as the leg was dancing up and down. The second in command, Major Colquhoun,[81] came over and produced a quart flask of brandy from which I had a good swig. I was then carried down to Gully Beach Dressing Station, where I managed to persuade the Doctor to remove the bullet. (This was contrary to their usual practice owing to the very great danger of introducing infection.) I turned over on my face on his operating table and after a couple of minutes I held the bullet in my hand. [This proved to be the start of a collection.]’

He was evacuated to Port Said on HMHS Grantully Castle and admitted to the New Zealand Hospital, where he met Bernard Freyberg. He was given the option of returning to England, but as he had promised his CO that he would return to the peninsula, he did so after being passed fit on 17 August 1915.

Mesopotamia

Memoir: ‘The distance between our troops and the Sunnaiyat position was about 500 yards and men were falling all over the place. I, as Staff Captain, was supposed to keep the men moving towards the Turkish position, and whilst bending over one party, received a sniper’s bullet through the jaw [9 April 1916]. I was carried back to a slight trench, where I sat down. My throat was bandaged, but I thought this was the end as my legs and arms started to go cold. Luckily for me, the Regimental Doctor of the King’s Own arrived, had one look and removed the bandage. A basin of blood was immediately shot out into the trench, and he said “Damn it all, you’re choking him, and his jaw is broken, bandage him higher up.” Which they did and I was much more comfortable.

We had to remain where we were until the evening, when we were carried on stretchers to the river hospital steamer. I was tied to an upright, and not allowed to lie down. The medical arrangements made by the Tigris Corps were dreadful. The open scows were drawn behind the steamer, and all stretcher cases were laid in rows, with not enough Orderlies to attend to the wants of the patients, and the dying and the living lying side by side.

On arrival at Basra we were taken to the very small Base Hospital there, where we were washed and made more comfortable .. [We] were eventually put on board Hospital Ships at Basra, to be taken to Bombay for fuller examination … On arrival at Bombay we were taken to the Main Hospital, where for the next two days I was X-rayed several times while they hunted in vain for the bullet which had entered at the point of the jaw and was eventually found over the heart and close to the Subclavian Artery. The Doctors at Bombay would not operate and I was sent home on the hospital ship Grantully Castle … We only sailed as far as Alexandria, when some of us were taken to the hospital there. Here they were very keen to operate, but the weather was intensely hot and I said that I would much prefer to go on to England where conditions were much better, the weather cooler, and I might get home to see my Father and Mother and other members of my family.’

‘Subclavian vessels would be very close: damage best avoided in my view! Jaw injury such that he could not chew and was thus placed on a liquid/mushy diet.’

Guards Hospital, Millbank, London

Memoir: ‘… when we reached London we were allowed to go to whichever Hospital we liked .. I asked to go to Millbank, the Guards Hospital, opposite to the Tate Gallery. On my arrival there I found I was put into B Ward, also known as the Mauve Ward. The chief surgeon was Colonel Pilchard assisted by a Captain from Harley Street.’

‘“Colonel Pilchard” was almost certainly Edgar Montagu Pilcher CB DSO FRCS (1865-1947), Professor of Surgery at the Royal Army Medical College, Millbank, since August 1910.’

Above: Edgar Montagu Pilcher

Memoir: ‘They soon had me up in the X-ray Room where they took my photograph, not [a] very good one of me but at least a very good one of the bullet, showing where it was and how close to the heart.’

‘I would maintain from the image available to me that the risk was to major vessels in the root of the neck rather than heart - bearing in mind that damage to these vessels is not to be recommended!! Subclavian artery (and vein would be very close by) with the Carotid Artery and Jugular vein to and from the head not at all far away!’

‘The other object on the X-ray is interesting, a wire-like thing. After magnifying the image there seems no evidence that his ribs were split and thus wired closed. Might it have been a marker taped onto the skin as a guide to positioning of the bullet tip to assist in the exploration? (It can be difficult to locate and any aid to localisation helpful. In my day used a sort of chicken wire grid sort of thing!) This one as the look of a ladies’ hair grip.’

Memoir: ‘[The morning after the operation Pilcher and the Ward Sister] removed my bandages in order to have a look and pull out the packing. I yelled, “For goodness sake leave my heart and guts inside and don’t pull them out as well” … Apparently, it had been a tricky job to remove the bullet. They had made an incision above my collarbone and had gone downwards under the ribs towards the heart and finally spooned out the bullet (which I still have) together with all the pus and other matter which had collected around it during the four months it had lain there.’

‘His notes indicate “incision above collar bone and gone down under my ribs towards my heart”. Not the type of incision to access heart space in my view, but ideal for the exploration of the collarbone area. The X-ray seems to show the bullet superficial to collar bone.

Above: Dowding's x-ray showing the bullet

The amount of time the bullet had been there, there would be considerable reaction, indeed abscess cavity formation around the bullet which would be drained and cleaned out, carefully. It would then be packed with antiseptic soaked gauze (Bismuth Iodine Paraffin Paste often the antiseptic used). Since it was packed under the anaesthetic it would be packed firmly and the wound would not be completely closed to allow drainage. Removal of this packing would indeed be testing for him. Subsequent packing and dressing would be lighter and thus much more tolerable.

I remain perplexed by the angle and orientation of bullet in neck - bullet passing through jaw and lodging in neck /chest would be tip down not tip up as seen, unless transit through jaw had altered trajectory/orientation.’

Memoir: ‘I was then passed on to Sir Francis Farmer who started to repair my jaw. He placed a type of gag in my mouth and on the right side wired a bar of studs to the teeth of both upper and lower jaws. He then wired the studs together and every three days came back and tightened the wires, gradually forcing the right hand side of my jaw upwards towards the gag.’

Above: Sir Francis Farmer

‘Farmer was a dental surgeon with an interest in gunshot wounds to the face, having started his work with such injuries during the Boer War. He was/is not as well-known as Harold Gillies but worked in the broadly the same field with Gillies more in plastic surgery for soft tissue repair. Dowing’s description of his repair is pretty much in line with practice - wire the jaw and gradually adjust tension in the wiring until teeth are aligned as much as practicable and then allowed to heal - meantime tube feed. Certainly photographs taken post treatment in later life would indicate job well one!’

Dowding’s next wound was at Bourlon Wood on 23 November 1917, during which his battalion lost a number of officers, including its CO, Lieutenant-Colonel William Kennedy. Dowding was wounded in the left leg by a high explosive shell. He remained with the battalion for some time before being sent to the Casualty Clearing Station. He was rebandaged and sent to Boulogne, from where he was evacuated to the London Hospital in Whitechapel. He was visited there by Colonel Kennedy’s widow and several of Kennedy’s academic colleagues from Cambridge University. He was in hospital for six weeks before being discharged to the Lauderdale Convalescent Home in Scotland. He returned to France during the tumultuous last week of March 1918.

Dowding’s memoir gives no account of the accidental injury to his collarbone that hospitalised him at the start of 1919.

Notes:

[1] Burton Observer, 15 August 1940. The five fronts listed were Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, France, North Russia and South Russia. We have found no evidence that Dowding served in South Russia, but he has a claim to a fifth Theatre of War, Egypt.

[2] Dowding was awarded a Regular Army Emergency Commission on 19 December 1939 on the General List. He was made War Substantive Lieutenant Colonel on 26 May 1941 and Temporary Colonel on the same day. The London Gazette of 21 December 1943 reported that ‘War Substantive Lieutenant-Colonel C.C. Dowding DSO MC, General List, relinquishes his commission and is granted the hon. rank of Colonel’. See below, for his Second World War career.

[3] ‘Colonel Morrison’ was probably (Sir) Edward Whipple Bancroft (‘Dinky’) Morrison (1867-1925), Canadian militia officer and journalist, later CRA 2nd Canadian Division and BGRA Canadian Corps.

[4] The Scotian was built by Harland & Wolff in 1898 for the Holland-America Line and was originally named the SS Statendam. It was sold to the Allan Line and renamed in 1911. It sailed regularly between Canada and the United Kingdom either to Glasgow or Liverpool, but not to Southampton.

[5] Dowding’s own account has him joining on 13 September; his AF B199a says 15 September. King Edward’s Horse (The King’s Overseas Dominions Regiment) was formed in 1901 and was composed of colonials resident in Britain. In 1913 it became part of the Special Reserve. The 2nd King Edward’s Horse was raised at his own expense in 1914 by J. Norton-Griffiths MP (‘Empire Jack’) (1871-1930), a civil engineer prominent in tunnelling.

[6] Dowding spent three years in India during his pre-war service in the ranks of the Royal Artillery, see below.

[7] These attachments and transfers were reported in the London Gazettes, 3 February and 19 February 1915, and the Birmingham Daily Post, 8 May 1915. 13th Reserve Cavalry Regiment was formed on mobilization in August 1914 and affiliated to the 14th and 20th Hussars. Dowding’s AF B199a dates his commission in the King’s Own from 30 December 1914. In his own account, Dowding states that he joined the King’s Own at Aldershot in March 1915 ‘where [he] filled the last vacancy they had’.

[8] The 6th King’s Own War Diary in the National Archives (TNA: WO95/5156-6) is limited to the period 1-29 February 1916. The cover sheet of the diary has been annotated as follows: ‘No trace of diaries for Dardanelles or Mesopotamia campaigns’.

[9] His Army Form B199a gives the date of September 1915 for his promotion to Captain and appointment as Staff Captain, 38 Brigade.

[10] 13th (Western) Division was the only British infantry division to take part in the Mesopotamia campaign.

[11] 38 Brigade War Diary reported that Dowding was wounded badly in the face during the morning of 9 April and evacuated: TNA: WO 95/5155.

[12] Dowding applied for a pension for this wound, post-war, although it is not clear whether he received one.

[13] TNA: MH 106/1700

[14] Sir Francis Mark Farmer (1866-1922), pioneering dental surgeon, who made important contributions to facial reconstruction, working at QAMH, a major centre for jaw injuries, and alongside the famous Harold Gillies at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup.

[15] The MC citation is from The Broad Arrow: The Naval & Military Gazette, 2 August 1916

[16] The MC award and the MiD were both made to ‘T/Captain C.C. Dowding, General List, New Armies’.

[17] TNA: WO95/2611 War Diary of the 11th Battalion King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment), 15 April 1917. Dowding arrived at the battalion the day after its CO, Lieutenant-Colonel A.G. Macdonald, had been wounded. Dowding’s AF B199a states that he joined the 18th King’s Own, which is incorrect.

[18] See Peter Simkins, ‘“Each One a Pocket Hercules”: The Bantam Experience and the Case of the 35th Division’, in Sanders Marble, ed. Scraping the Barrel: The Military Use of Sub-Standard Manpower (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), pp. 79-104

[19] Responsibility for the reorganization fell to Harold Ruggles-Brise. See James Barker-McCardle & Alan Ogden, The Caring General: The Military Life and Letters of Major-General Sir Harold Goodeve Ruggles-Brise (Warwick: Helion, 2023), Chapter 9.

[20] Bexhill-on-Sea Observer, 23 April 1917. See also, http://www.eastsussexww1.org.uk/canadians-bexhill-sea/index.html

[21] For Crozier, see Charles Messenger, Broken Sword: The Tumultuous Life of General Frank Crozier 1879-1937 (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2013) and Michael Anthony Taylor, No Bad Soldiers: 119 Infantry Brigade and Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier in the Great War (Warwick: Helion, 2022).

[22] See Taylor, No Bad Soldiers, pp. 154-63

[23] TNA: WO 95/1971. War Diary of the 18th Battalion Welsh Regiment, 23 November 1917

[24] TNA: MH 106/1692

[25] He was described as ‘T/Major Welsh Regiment’.

[26] He was described as ‘T/Major Charles Child Dowding MC, Welsh Regiment’. This was a King’s Birthday Award, granted for cumulative service, with no citations published. The medal was presented by Prince Arthur of Connaught at St James’s Palace on 13 October 1919: TNA: WO390/7/1. We owe this information to William Spencer.

[27] TNA: WO95/3021. War Diary of the 5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, 8 May 1918.

[28] J.C.J. Elson, The War History of the 1/5th South Staffordshire Regiment (T.F.) 1914-1919 (Rugeley: Elson Publishing, 2016), p. 137. On his arrival, Dowding was described as ‘King’s Own’. We are grateful to Mr Elson for a copy of his book.

[29] TNA: WO95/2685/2. War Diary of the 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, 3 October 1918. Dowding was described as ‘Major C.C. Dowding DSO MC (King’s Own Lancaster Regt.), attached 5th South Staffs Regiment’. For Evans and the other COs of 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment before Dowding, see Appendix 1, below.

[30] Supplement to the London Gazette, 4 October 1919. Lance Corporal (later Sergeant) W.H. Coltman DCM MM, a stretcher bearer in the 1/6th North Staffords, was awarded the Victoria Cross for ‘his gallantry in bringing in the wounded from badly exposed positions on Mannequin Hill’ on the same day. Dowding signed the VC recommendation.

[31] Downing’s military memoir is rather fragmentary and confusing in its depiction of his service in 1918, both as to the units he was with and when. For example, his assumption of command of the 1/6th North Staffords after the death of Colonel Evans is not mentioned.

[32] It seems that Dowding saw himself as a King’s Own officer. His headstone in Taruheru Cemetery, Gisborne, New Zealand, describes him as ‘Colonel C.C. Dowding DSO & Bar MC, King’s Own Royal Regiment’. His AF B199a also identifies him as a King’s Own officer.

[33] TNA: MH 106/1697

[34] The London Gazette described him as ‘T/Major (acting L/Col) C.C. Dowding DSO MC, R. Lancs. R. attd 1/6th North Staffordshire Regiment [Mannequin Hill, 3 October 1918]’.

[35] It seems that she was the ‘nice Scotch nurse’, who held his hand as he entered the operating theatre at Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital in 1916: Dowding, Unpublished Memoir, p. 29.

[36] John Dowding fought in the Second World War with the NZEF.

[37] The was reported in the Nairnshire Telegraph. His parents-in-law were natives of Nairn. In his unpublished memoir Dowding stated that he sailed for Russia in August 1919.

[38] Material began accumulating in the 1920s, see Michael Jabara Carley, ‘Review Article: Allied intervention and the Russian Civil War, 1917-1922’, International Review of History, 11 (4) (1989), pp. 689-700. For recent accounts, see Damien Wright, Churchill’s Secret War with Lenin: British and Commonwealth Military Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1918-20 (Warwick: Helion, 2017) and Anna Reid, A Nasty Little War: The West’s Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution (London: John Murray, 2023).

[39] The evacuation was conducted under the command of none other than Sir Henry Rawlinson. There was some controversy. A government ‘Blue Book’ was published and presented to Parliament in order to explain the reasons for the evacuation and the measures taken to ensure the safety of British forces. This has been reprinted by the Naval & Military Press. For Archangel, see W.E. Ironside, Archangel 1918-19 (Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, n.d.). ‘Tiny’ Ironside, the future Chief of the Imperial General Staff (1939-40), commanded the Archangel expedition, 1918-19. See also, G.R. Singleton-Gates, Bolos & Baryshynas: The North Dvina 1919 (1920; Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, n.d.). For Murmansk, see Major-General Sir C. Maynard, The Murmansk Venture (Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, n.d.). Maynard was commander of the Allied forces in Murmansk, 1918-19.

[40] Dowding, Unpublished Memoir, p. 52

[41] London Gazette, 3 February 1920. He was described as ‘Colonel C.C. Dowding DSO MC 5th North Staff. R. (T.F.), (T/Maj. 18th Bn. Welsh Regiment)’.

[42] Reported in a Supplement to the London Gazette, 3 December 1919. He relinquished the temporary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel on ‘ceasing to be empld.’ His AF B199a states ‘relinquished commission on completion of service and granted the honorary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel’.

[43] Messenger, Broken Sword, p. 116.

[44] Messenger, Broken Sword, p. 117

[45] TNA: FO 371/3626, quoted in Messenger, Broken Sword, p. 121. Cubitt added that ‘care should be taken to avoid giving the impression that [Crozier] is one of the British Military Representatives [in the Baltic] or in the British Service. It seems important in any official dealings with him he should be regarded and treated simply as an officer in the Lithuanian Army’.

[46] Dowding’s AF B199a gives ‘Foreign Office, Kovno’ as the authority for his promotion to Colonel.

[47] The Dominion, 25 (68) (14 December 1931), p. 12. The Dominion newspaper was published in Wellington from 1907 to 2002.

[48] Messenger, Broken Sword, p. 123

[49] See Charles Fair, ‘From OTC to OCB: The Professionalisation of the Selection and Training of Junior Temporary Officers During the Great War,’ in Spencer Jones, ed., The Darkest Year: The British Army on the Western Front 1917 (Warwick: Helion, 2022), pp. 78-109

[50] Fair, ‘From OTC to OCB’, p. 81

[51] Keith Simpson, ‘The Officers,’ in Ian F.W. Beckett & Keith Simpson, eds., A Nation in Arms: A Social Study of the British Army in the First World War (London: Tom Donovan, 1985), p. 72

[52] The Officers Training Corps was authorised in 1908, as part of the ‘Haldane Reforms’, that also saw the creation of the Territorial Force, the Special Reserve and the British Expeditionary Force.

[53] There is a possibility that the Dowding family also farmed for a time in Norfolk.

[54] England & Wales, Civil Divorce Records, 1858-1918, 1890 03971-Dowding

[55] Farming was abandoned at some point between 1890 and 1901.In the 1901 Census Martha is described as being in business on her ‘own account’, letting furnished apartments in Cromer. Their boarding house at 4 Cabbell Road, Cromer, appears in Kelly’s Directory of Norfolk (1904), p. 102.

[56] Hampshire Archives 68M85W/A1: National School Admissions Registers & Log Books, 1870-1914, Winchester, Hampshire

[57] Norfolk Record Office C_ED_4_78: National School Admissions Registers & Log Books, 1870-1914, Bracon Ash, Norfolk. Norah Dowding also attended Leighton House School, which appears to have been a small, modest proprietary school, located at 11-13 St Mary’s Road, Cromer. This information was stated on Norah’s application form to join Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service in 1916. See TNA: WO 339/2323.

[58] TNA: WO 96/1409/85

[59] His engagement appears to have been 7/5, seven years with the colours and five with the Reserve. His time with the colours would have expired on 3 March 1908.

[60] In the 1901 Census Carrie was described as the ‘Manageress of a Bazaar’, with the fourteen-year-old Norah as her ‘Assistant’. In the 1911 Census Carrie was described as ‘Assistant’ in the boarding house business. Winifred married an accountant, Joseph Willis, in 1905. He inherited the East Cliff Hotel and Boarding House, 17-19 Tucker Street, Cromer, and ran it for a short time: see Kelly’s Directory of Norfolk (1904), p. 104.He got out of the hotel business in 1907 and moved away from Cromer, but his wife ran the Firs Boarding Establishment in Lowestoft, see Norfolk News, 9 January 1909. Winifred died from peritonitis on 1 October 1926, aged only 45.

[61] Norah was the only Dowding who moved in elevated social circles, though not as a social equal. One of the referees on her application form for Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service was Lady Grace Barry of Witchingham Hall, Norfolk.

[62] At her death, in 1977, Norah Mack was comfortably off, leaving £77,431.

[63] His Attestation Form for King Edward’s Horse states his height as 6’ 1½”.

[64] It is interesting that Dowding sought a commission as soon as the war broke out. He obviously saw himself as ‘officer material’.

[65] See Kent Fedorowicz, ‘The Migration of British Ex-Servicemen to Canada and the Role of the Naval &Military Emigration League, 1899-1914’, Social History, 35 (49) (May 1992), pp. 75-99. One of the issues to concern the British authorities was whether British Army Reservists should be allowed to emigrate. Dowding was a Reservist until 3 March 1913.

[66] The Canadian Census of 1921 has him farming at East Chilliwak and working ‘on his own account’.

[67] Alice was British born at Ulverston, Lancashire, but the family had been in New Zealand since 1879.

[68] Dowding had this in common with Douglas Haig, who also met his wife on the golf course and proposed marriage within thirty-six hours.

[69] Poverty Bay Herald, LV (17387), 11 October 1930, p. 13

[70] Alice was eleven years older than Charles. Someone seems to have been sensitive about the age difference. Alice’s year of birth is incorrectly entered in the 1939 Register of England and Wales (as 15 January 1881); on the passenger list of the SS Rotorua in 1933, she is shown as being only two years older than her husband (50/52).

[71] Also known as the Napier Earthquake. It measured 7.8 on the Richter scale, killing 256 people, making it New Zealand’s worst natural disaster.

[72] The SS Rotorua’s passenger list distinguishes between British and New Zealand passengers. The children were ‘British’, but Charles and Alice were New Zealanders. This strongly suggest that this was the children’s first trip to New Zealand.

[73] The biggest gap in our knowledge of Dowding’s military activities is that between his return from Lithuania in January 1920 and his reporting to No. 1 AMPC Depot on 19 December 1939. He was entered into the England and Wales Register on 29 September 1939 while staying with his mother in Cromer. He described himself as ‘Farmer New Zealand. Lieutenant-Colonel Reserve of Officers’. No trace of him as a Reserve officer has been found in the Army List, but he had held the honorary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel since 1919.

[74] New Zealand Herald, LXXVII (23577), 10 February 1940, p. 13

[75] Opotiki News, VI (710), 26 October 1943, p. 4. Opotiki was a small town on the south-eastern edge of the Bay of Plenty. The Opotiki News was founded in 1938.

[76] The last destroyer out of Dunkirk was HMS Shikari on 4 June 1940.

[77] Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1900. The report says that commissions were offered to Oxford graduates, but this appears not to be the case with Odling, who had not graduated by March 1900.

[78] He took his degree in May 1916 after London University decided to confirm degrees on any officers who had almost finished their degree requirements.

[79] His mother was only eighteen when he was born; she had a further eight children and died, miscarrying what would have been her tenth child, aged 34, on 28 March 1898, when Tom was 14.

[80] Evans’s marriage was apparently unhappy. In 1911 his wife and children went to Canada to visit his wife’s mother and sister, with the intention that Evans would follow, but he never did. He had a close, probably platonic, relationship with a woman called May Jones. On Evans’s death, army administration followed protocol and informed his ‘next of kin’. As far as the army was concerned, this was his wife, in British Columbia. This, and Evans’s failure to write a will, resulted in a bureaucratic struggle between his wife, his family in Britain and May Jones, which can be followed in the pages of his service file.

[81] Major H.W.C. Colquhoun, Indian Army (Retd). He commanded the 6th King’s Own from 9 September 1915.