HM Submarine H5: The Submarine Cover-Up in Caernarfon Bay 2 March 1918.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- HM Submarine H5: The Submarine Cover-Up in Caernarfon Bay 2 March 1918.

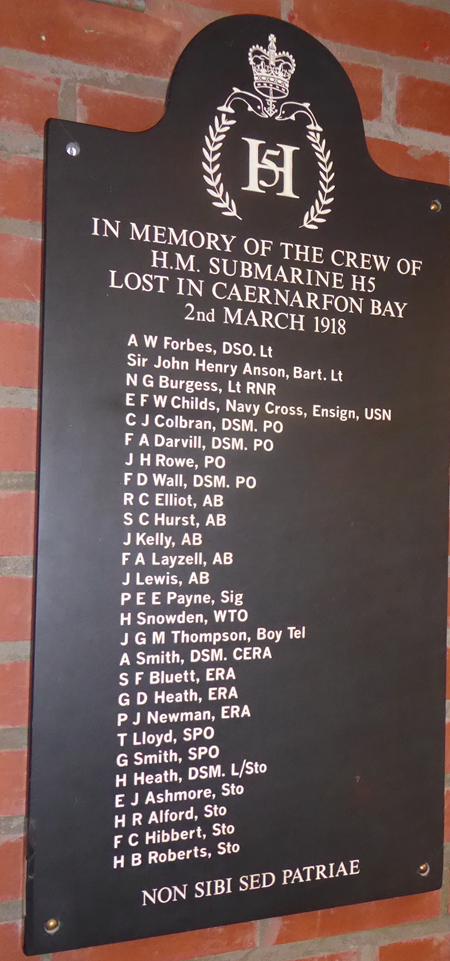

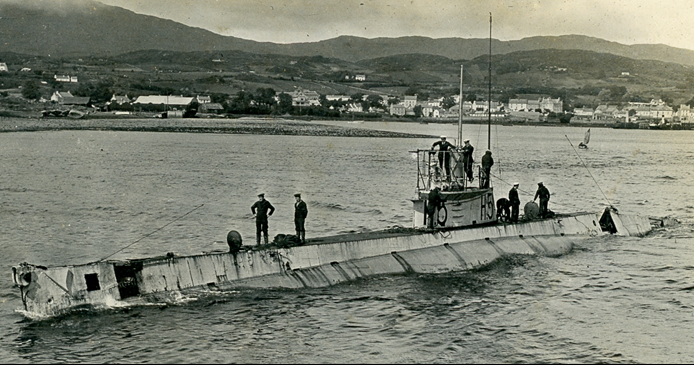

HMS H5 was a Royal Navy H-class submarine built by Canadian Vickers, Montreal and launched in June 1915. She was soon in action sinking the German U-boat 51 in July 1916 but was herself sunk after being rammed by the by the British merchantman S.S. Rutherglen when mistaken for a German U-boat on 2 March 1918. Sadly, all on board perished but are commemorated at Chatham Naval Memorial and also at the Holyhead Maritime Museum Anglesey. It is only recently that the wreck site has come under the Protection of Military Remains Act.

Above: memorial at Holyhead Maritime Museum, Anglesey

Along with the 26 crew that day was an observer, US Navy Lieutenant Earle Wayne Freed Childs from the American submarine AL-2. As a result, he became the first US submariner to lose his life in the First World War and whose story is completed later in this piece.

Above: Submarine H5

Having been built in Montreal, HMS H5 was among the first submarines to cross the Atlantic. Her armament was four 18-inch (45.72 cm) bow torpedo tubes for eight torpedoes. H5’s standard complement was twenty-two crew, but by 1918, H5 would house twenty-six men.

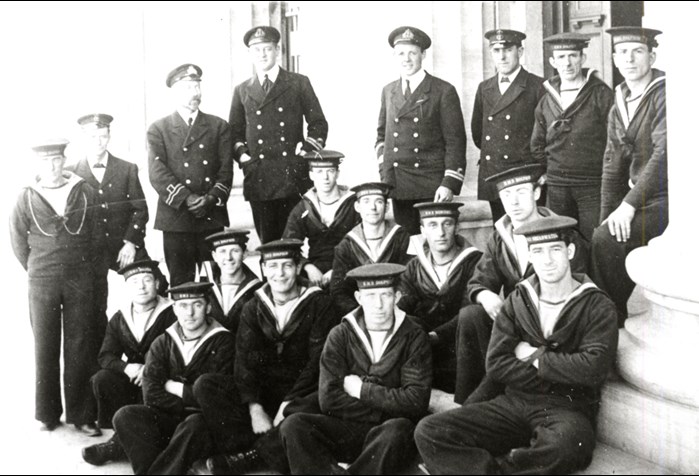

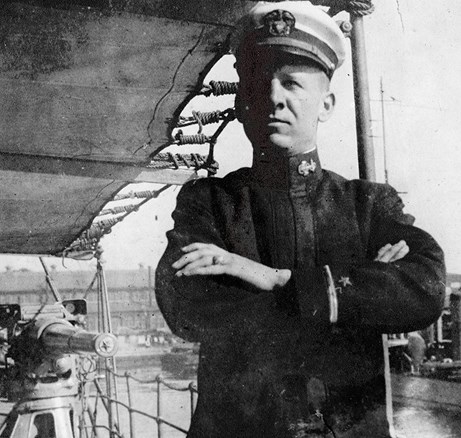

Lieutenant Cromwell Hanford Varley was assigned as one of H5’s first commanders. Operating for a time from Harwich, she sank U51 on 14 July 1916. Later spending her time in the Irish Sea at Queenstown and Rathmullen, from September 1917, she joined a flotilla of submarines based at Berehaven in Bantry Bay and at Killybegs, Ireland working from the depot ships HMS Vulcan and HMS Ambrose. It was her role to intercept German U-boats operating around the Irish coast, and in the Western approaches and Irish Sea. After Varley left H5, Forbes took over, being an officer of great repute and highly regard. By 1918, her crew consisted of twenty-six men. Five men held Distinguished Service Medals, and the commander held a Distinguished Service Order. One crewman was possibly descended from the famous Anson family (see below).

The crew of H5 perished on the 2 March due to a number of unfortunate circumstances:

- The presence of U-boats in the Irish Sea meant that picking up survivors was a risk to any ship that attempted it. Previous experience of ships being torpedoed after stopping to help others led the British Admiralty to advise that ships should abandon survivors to save themselves.

- British submarines, like their German counterparts, varied greatly in their shape and size. Without special knowledge of British submarine outlines, observers had to rely on identification marks to discern friend from foe.

- Weather could exacerbate identification and in H5’s case it was night time, visibility was poor, and merchant traffic did not know of H5’s presence. Whilst the number of submarines lost to friendly fire in the Great War is low compared to the total sunk. (4 out of 56) almost all of those incidents involved a signal or insignia being confused, missed, or not identified in time.

As stated earlier, H5 had begun operations with a victory in July 1916 under the command of Cromwell H. Varley, RN, when she torpedoed the U-boat U51 and was photographed flying the Jolly Roger on returning to Yarmouth from her patrol in the Bight (14 July 1916). Although this is not the first time a British submarine flew the Jolly Roger to celebrate a victory, it is the first known photograph of one. (RN Submarine Museum)

Above: Flying the Jolly Roger 1916 (RN Submarine Museum)

By a twist of fate, on 28th July 1919, the British Prize Court awarded the crew of H5 a £175 bounty for the sinking of U51but of course by that time they had already perished.

Above: The crew of H5 (National Museum of the Royal Navy)

The happier times of July 1916 were soon to be replaced by tragedy when a message was received on 7 March 1918 by Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayley, Admiral Commanding Western Approaches from Captain Martin Nasmith VC of SS Rutherglen

“SS Rutherglen has rammed a submarine at 20.30hrs. on the 2nd March within position Lat. 53 4’ N, Long. 4 40’ W. The submarine was crossing bow at considerable speed. After collision cries were heard and men seen in the water, also there was a strong smell of petrol vapour. Forepeak of “Rutherglen” is flooded”.

SS Rutherglen, under orders to not risk falling victim to other submarines nearby, pressed on having rescued no one. Unbeknown to either Captain Nasmith or the Admiralty, the Rutherglen had struck H.5. This may well have been due to the fact that by the end of 1917, American and British forces were cooperating in their efforts to hunt down U boats in the Irish Sea. In early 1918, ‘Operation GF’ was put in place in which eight British submarines collaborated with the USS Bushnell and seven AL class submarines around the coast of Ireland and in the Irish Sea. As part of the partnership, US naval officers undertook familiarisation trips on board the British submarines. Such was the secrecy of the whole operation that convoy escort ships and merchant ships were not told that there were British submarines operating in the area.

The US Navy was stationed in Berehaven during WW1, while protecting the sea lanes off southern Ireland. American battleships and submarines anchored in the sheltered harbour off Bere Island, while in between patrols, where they would be protected by the extensive gun batteries on the island. American sailors came ashore to Rerrin village visiting the island shop, sending mail home from the local post office, and played baseball on a baseball diamond laid out at the British Admiralty Recreation Grounds in Rerrin.

On 26 February 1918, H5 sailed from Berehaven under the command of Lieutenant A. W. Forbes, with US Navy Liaison Officer Earle Childs on board for instructional purposes and was expected to return to port on the morning of the 6 March. It was only after subsequent investigations into the disappearance of H.5 and the ramming of an unidentified submarine in that location was it realised that the Rutherglen had sunk H5.

Captain Nasmith recommended leaving the Rutherglen crew under the impression that they had indeed sunk an enemy submarine. The ship’s muster were never told of the mistake and were even given a bounty for sinking what they thought was a German U-boat.

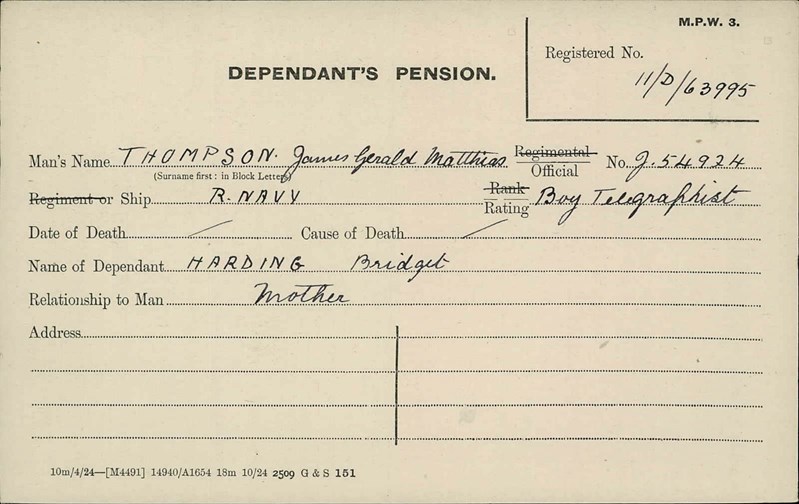

The youngest crew member on board H5 was Boy Telegraphist James Gerald Matthias Thompson J/54924, the son of Bridget & Nelson John Thompson, of Portsmouth. Educated at the Royal Hospital School, Greenwich. He joined the Navy on 22 June 1916 at the age of 15 as Boy 2nd Class on board HMS Ganges and by 25 November 1916 became Boy Telegraphist. On 1 July 1917 he transferred to H5 and died on board on 2 March 1918 aged 17 years old.

Above: Pension card of James Gerald Matthias Thompson

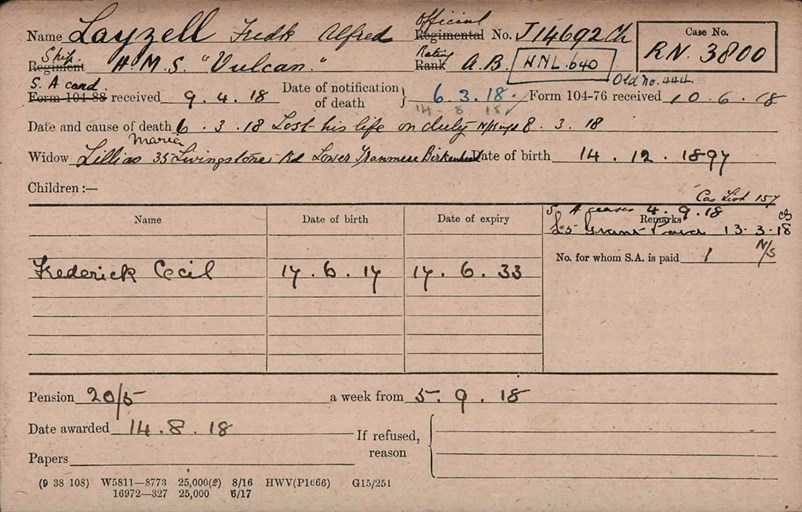

Able Seaman Frederick Alfred Layzell (J/14692) was the son of Mr. and Mrs. John Layzell, of Little Maplestead, Halstead, Essex and the husband of Lillian Maria Layzell, of 35, Livingstone Rd., Lower Tranmere, Birkenhead. He was aged 22.

Above: Frederick Alfred Layzell

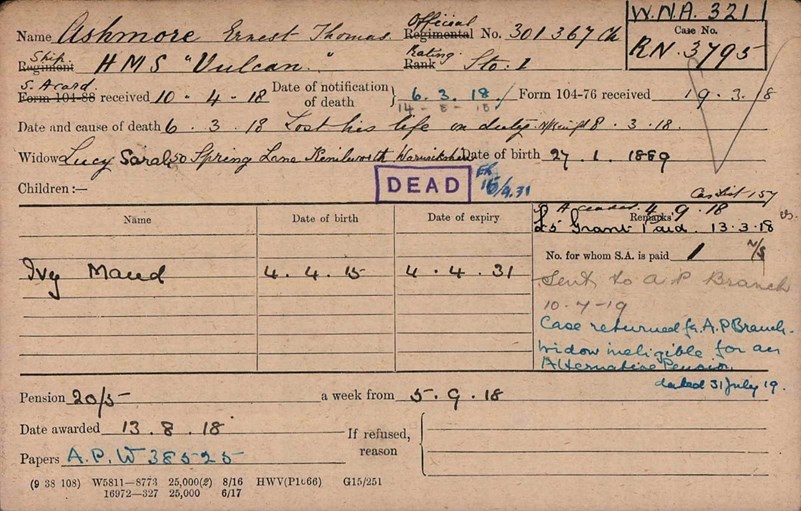

Stoker 1st Class Ernest Thomas Ashmore (301367)was the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Ashmore, of 5, Humphries St., Emscote, Warwick and the husband of Lucy Sarah Ashmore, of 50, Spring Lane, Kenilworth, Warwickshire. He was aged 36.

Above: Ernest Thomas Ashmore

Lieutenant Sir John Henry Algernon Anson 5th Bart, aged 21, was the son of Rear-Admiral Algernon Horatio Anson, 4th Bart., and the Hon. Adela Anson.

Above: Sir John Henry Algernon Anson

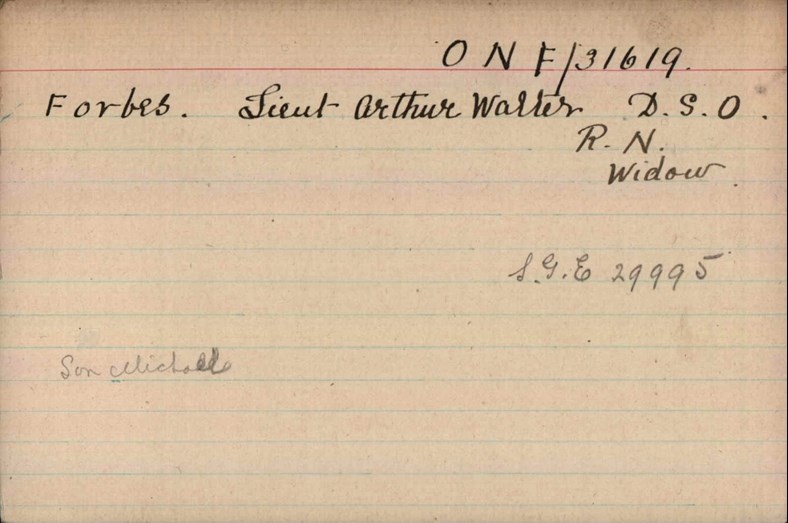

Lieutenant Arthur Walter Forbes DSO was the son of Helen Forbes – he perished aged 26.

Lieutenant Earle Wayne Freed Childs from Philadelphia was 24 years old and was on board as an observer. He was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross by the president of the United States “for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service while serving as an Observer on board the British Submarine HMS H5, engaged in the important, exacting and hazardous submarine duty in the War Zone, during World War I”. His wife gave birth to a baby just days after the sinking.

Above: Earle Wayne Freed Childs

A memorial service took place on 2 March 2002 in Holyhead, Anglesey when the memorial plaque pictured above was unveiled.

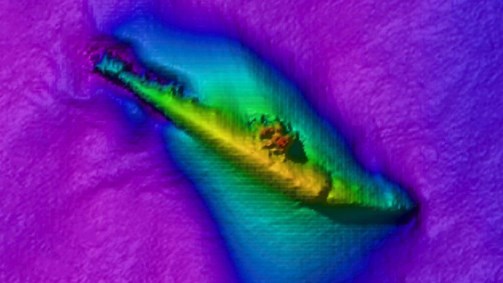

Recently technology has been used to capture a new and more detailed view of a British submarine which sank in Caernarfon Bay in March 1918.The colour image shows the broken hull of H5.

Article by Robert Stone

References and Sources

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/community/3514

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/6296063

https://astreetnearyou.org/regiment/9695/Royal-Navy

https://www.walesonline.co.uk