George Horey's Parents’ Pilgrimage to the Somme 1923

- Home

- World War I Articles

- George Horey's Parents’ Pilgrimage to the Somme 1923

Some of the most moving photographs in the 40-year archive of The Western Front Association are those featuring the bereaved – the people forced to pick up the pieces and continue with their lives having lost a loved one in the war. Their pain all too often appears visceral.

That is very much the case with these pictures of London tram conductor George Joseph Horey and his wife Margaret, although the comfort the pair were getting from being able to visit the site where their son is buried is also palpable - serving to highlight just how difficult it must have been for those who had no known grave to visit or whose circumstances (geographic or economic) stopped them from being able to go on such a trip.

The story of the Horey pilgrimage was first featured in the Bulletin back in 1996 courtesy of Surrey branch member Jim Crawford – the photographs and family background having come courtesy of Mrs Olive Manley, the maternal granddaughter of the two people pictured, and a former secretary of Jim’s.

Olive was the daughter of Florence Horey, who was one of the siblings of the fallen soldier: Private George Joseph Horey, who died of wounds in August 1918 having been injured in action on the Somme whilst serving with the 12th London Regiment.

The Horeys were not a wealthy family and had only been able to get to France courtesy of the St Barnabas Pilgrimage – a fully subsidised undertaking that enabled “very poor people” to visit the graves of loved ones on the Western Front. This trip, to the Department of the Somme in September 1923, was the second such charitable pilgrimage funded by the organisation; with one having gone to Flanders earlier in the year. More than 800 bereaved were on each of the two trips.

Like all of the participants, the Horeys would have arrived at Victoria Station on the evening of Saturday, September 29, in good time to board a special train due to reach Boulogne at 3.30am.

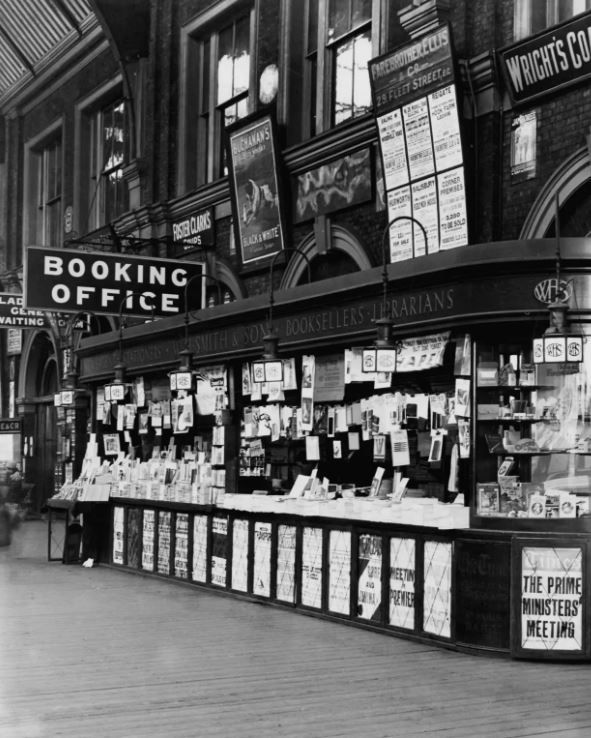

Above: The W.H. Smith bookstall at Victoria Railway Station photographed the year after the pilgrimage, in January 1924

After breakfast, the pilgrims were split into groups selected on a geographic basis according to where their loved ones were interred – the options being Boulogne, Etaples, Amiens, Albert and Bethune.

There were 253 pilgrims in the Horeys’ ‘Albert’ group. This party lunched first at the Picardie and Paix Hotels before being packed into every available car and lorry that Albert could provide and heading off to an incredible 75 different cemeteries.

Mr and Mrs Horey were bound for Daours Communal Cemetery Extension, and the fact that they kept not only the photographs of the visit but also the tickets issued for it is perhaps indicative of the measure of value they placed upon the whole undertaking.

Above left: Mr George Horey standing behind his son's headstone al Daours Communal Cemetery Extension on September 30, 1923

Above right: Mrs Margaret Horey laying flowers as the grave of her son.

Above: Daours Communal Cemetery Extension (c) CWGC 2021

Their son, Private George Joseph Horey, had enlisted at Poplar, London, and served with the 29th London Regiment before being transferred to the 12th London Regiment -‘the Rangers’. He died of wounds on August 25, 1918.

The Pension Record Card, showing George's mother's address.

According to ‘The Rangers' records: “Information was received on 22nd August that the enemy were to deliver a strong counterattack upon the position handed over to the Rangers by the 47th Division. ln consequence the Rangers were ordered to `stand to' and at midnight were moved up to Tailles Wood. On the night of the 23rd-24th August the Brigade (175th) moved to an assembly position and attacked the enemy in conjunction with the 142nd Brigade, capturing their objective after a sharp tussle and sending at least 100 prisoners to the rear for incarceration. The casualties in the battalion being unfortunately very heavy.”

Above: Bois de Tailles, where George is thought to have received his fatal wounds, is marked (WFA TrenchMapper)

Daours Communal Cemetery Extension came close to becoming a front-line cemetery following the German’s main Spring offensive in 1918 and subsequent counterattacks to drive them back. It seems probable that Private Horey was one of the numerous casualties from the attack that went in on the night of 23rd-24th August. The fact that his grave lies a reasonable distance from the site of the attack suggests he had passed some way along the casualty clearing system before he succumbed to his wounds.

After their busy, emotional and tiring day, George’s parents were returned to Boulogne in time to catch a train that would arrive back at Victoria Station at 7am on the Monday.

Above: Victoria Station postcard c.1904

The whole trip had lasted some 34 hours and there had been no bed and little more than rudimentary washing facilities. Many of the pilgrims would have faced a considerable journey just to get to Victoria from homesteads across the country, and they would now have to repeat the challenge again. The Horeys, who were Londoners, were at least spared this.

The fallen soldier had three brothers and two sisters, and the mementoes of the pilgrimage would ultimately come into the care of his sister Florence (‘Flo’), who was married to a veteran of the war – Tom Foster – who suffered permanent deafness as a result of his war service. Their daughter Olive became the custodian of the items follow the death of her parents.

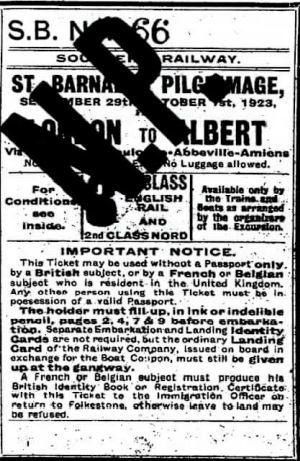

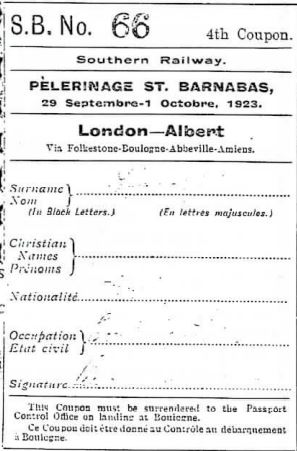

The ticket that survived the trip originally contained a number of coupons which should have been surrendered at various stages of the journey. It was available for use without a British passport on the trains and boats arranged by the organisers of the pilgrimage and did not allow the holder to carry any luggage. It is believed that the over-printed letters ‘NP’ suggest that the holder (Mr Horey) had ‘No Passport’.

Above: The front cover of the ticket issued to Mr Horey and one of the vouchers showing Mr Horey's details.

Original research Jim Crawford. Edited Dr Martin Purdy.