Horses on the Western Front by Elspeth Johnstone

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Horses on the Western Front by Elspeth Johnstone

Horses on the Western Front by Elspeth Johnstone

(This article first appeared in Gun Fire pp38-52. All issues are available to Western Front Association members to access via your member login.) (1)

You have shod them cold, and their coats are long, and their bellies stiff with mud;

They have done with gloss and polish, but the fighting heart's unbroke …

We, who saw them hobbling after us down white roads flecked with blood,

Patient, wondering why we left them, till we lost them in the smoke;

Who have felt them shiver between our knees, when the shells rain black from the skies,

When the bursting terrors find us and the lines stampede as one;

Who have watched the pierced limbs quiver and the pain in stricken eyes;

Know the worth of humble servants, foolish-faithful to their gun. (2)

At the beginning of August 1914, the Regular Army numbered 160,000. By the end of that year the Territorial Army and volunteers had increased the fighting force to over one and a quarter million men. The mobility of this fast expanding force depended almost entirely on the horse. Even though there was a huge growth in vehicle transport throughout the war, transport itself was regarded by most as horse transport. As John Terraine observed:

It must never be forgotten that throughout the war, in the midst of all the technology of the Industrial Revolution, the legs of men and beast provided the bulk of transportation in the battle areas.(3)

How, and where, were enough horses to be found to support the biggest army that Britain had ever sent to war? Plans for their provision had been put in place, in the eventuality of a European war, as early as 1912 by the Quartermaster General, Sir John 'Jack' Cowans. He realised that horses fit for work would be required within a few days of mobilisation. Provisions made previously by the Army Remount Department and the National Defence Act of 1888 were inadequate; and because of the growth of mechanical vehicles there was a decline in the number of available horses.

Until this time, the apparatus set up to produce enough horses at a moment's notice was administered by Remount Officers and a few knowledgeable civilians in a dozen areas of the British Isles. A pool of horses was on standby from livery stables, corporations and railways, which were required by law to supply a percentage of their livestock in the event of national danger. It was a small reserve of horses, about 25,000, and the peace establishment itself of the Army was the same number. Cowans had estimated an immediate need for at least 165,000 horses immediately; 42,000 for the BEF, 86,000 for the Territorial and a further three months supply in reserve to replace casualties.

Cowans set about restructuring the existing system by setting up Purchasing Commissions, who were given military authority. Owners not prepared to part with their horses had to prove them indispensable. In general, horses used for civilian food distribution were not requisitioned. Horses fit for work would be ‘impressed' and the commissions could call on the assistance of the local magistrates and the police to enforce requisition. A Horse Register was kept for each area giving the name and address of the owner, the total number of the horses owned and the number and type available for impressments. Proper guidelines for the collection and the despatch of horses to their destinations were put in place. Officers ensured that payment, from a fixed tariff of compensation, was made promptly.

Every unit was to know where its horses were coming from and every purchaser would know where to send them. Purchasers across the country were given a timetable ‘showing where trucks would be in waiting on each successive day of mobilisation and the nature of the horses required that day and the destination of the truck.’(4) This system of impressment increased the establishment of horses from 25,000 to 165,000 in twelve days! One year on, in August 1915, there were 368,000 horses on the Western Front, and the total of horses impressed eventually reached 467,973.

As an example of the number of horses impressed from any one business, Simonds’ Brewery of Reading (5) had 26 horses taken, mostly five to six year old mares, in just one month - August 1914. A premium was put on heavy draught horses (although smaller then than today) as they were essential to the artillery for pulling the heavier 60 pounder guns. Also, as Cowans realised, it only required two of them to do the work of four lighter horses. This would reduce congestion on the roads, and, typical of Cowans' logistical brain, they would require less shoeing!

Purchasing Commissions were also sent to Canada and North and South America. To avoid withdrawing officers from military duty, these commissions consisted of country gentlemen (such as large landowners and competent masters of hounds) who had a thorough knowledge of horses. In this way, by 11 November 1918, 428,608 horses were procured from Canada and North America, and 6,000 from South America. The Remount Service was eventually responsible for supplying not only the British but the American, Belgian and Dominion forces.

Horses bought in the United Kingdom were sent straight to the training units of the cavalry, artillery and Army Service Corps. Those from abroad were sent to Remount Depots, the largest of which were at Southampton, Bristol and Liverpool. At the start of the war the remount accommodation was for approximately 1,200 horses but grew to 60,000. Once there, the horses were kept in quarantine for three months and were then released for training. They were trained to ignore the sound of gunfire and to work in teams. For an experienced horse such as a hunter, a carriage or draught horse, this took a week or so. However, for those which had no experience or needed breaking in, it took longer.

Most men with knowledge of horses were encouraged to join the cavalry, artillery or the ASC, which led to a shortage of competent horse handlers at the depots. But as with many "behind the scenes' operations, women with a knowledge of horses were called upon to manage or help at the depots. However, numbers of inexperienced personnel were also employed and had to be trained Lieutenant-Colonel Kennedy Shaw" observed a new recruit to a Remount Depot repeatedly place a bit into the mouth of:

… a bored looking gun-horse. Naturally it dropped it out onto the ground. The man repeated the effort three times, and I then asked him what he was trying to do. Said he. "This brute won't hold the thing in his mouth for me to buckle them straps to!" He imagined, I suppose, that the bridle was to be built up piecemeal on the horse's head. (7)

After training and being passed as fit for work, the horses crossed to France with their divisions or were shipped to Remount Depots there, which had an establishment of 16,000 to 17,000 horses. Between 1914 and 1918 there were five Base Remount Depots and three forward Remount Depots in France.

Some of the vessels employed in shipping the horses had been in the business of carrying horses and cattle, so that ventilation, electric light, drainage and water laid to stalls were available. But many horses suffered bad conditions. Some had to stand in railed enclosures on deck, or in cramped, airless and unlit accommodation below deck, struggling to maintain their footing. They were cajoled up gangways or craned onto the boats, with slings around their bellies. Transport by sea and rail often left the horses debilitated. Lieutenant Colonel J W Yardley, Deputy Director Remounts, Reserve (later 5th) Army, gives an account in his diary (6 August 1916) of the problems encountered in the transportation of horses:

Conducted party from XIV Corps H. Art [Heavy Artillery] arrived BELLE EGLISE 1.15am. Detained 3 chargers, 28 HD (Heavy Draught] and handed them over. The remounts left ROUEN on Ist inst. And traffic [control] has been unable to trace them in spite of continual enquiries. They have travelled about since except for one hour during which the NCO in charge was able to detrain and exercise. Horses had no chance of water since 3pm. (8)

Even as late as 1918 the problem of neglect through the ignorance and inexperience of many of the horse handlers persisted. This caused unnecessary wastage. Lieutenant Colonel Yardley writes in his diary of 12 January 1918:

With DDVS (Deputy Director Veterinary Services] to BOUZINCOURT to interview 61st Division "Q" [Quartermaster] on large wastage of horses reported ... this only for one week and caused by large evacuations for debility ... officers needed in batteries to see that horses are properly cared for and proper stable management carried out. The artillery horses are badly cared for owing to ignorance and absence of officers [with the necessary knowledge] from wagon lines. (9)

In some quarters neglect was regarded as a serious matter. The ASC's 'Orders for Drivers' stipulated that:

When horses are placed on the sick list suffering from sore withers, saddle or girth galls, etc, due to neglect or carelessness, the driver will cease to draw corps pay until his horses return to duty, besides incurring any other punishment his commanding officer may award him. (10)

Eventually the appointment to every Corps of chief horse-masters who were experts in horse management and stabling went some way to alleviate negligence.

Only a small percentage of horses arriving on the Western Front was destined for the cavalry or as mounts for officers. The majority, light and heavy draught horses, were used by the ASC,(11) brigade and battalion transport, the artillery and field ambulances. The Royal Engineers used them to pull such vehicles as mobile pigeon lofts. Of 5,592 horses in an infantry division, the divisional artillery needed 3,814. Shire horses, for example Clydesdales, were an important requisite for pulling the heavier 60 pounder guns.

Thousands of light and heavy draught horses were used by the ASC in divisional trains to deliver the baggage, rations and supplies for the infantry and also their own forage of hay and oats. The forage ration of the 66' Division in France, depending on the size of the horse, was approximately 12-15 lbs. of hay per day per horse and 10-19 lbs. of oats. (12) The daily requirement for each division was 30 tons. Bran, linseed, barley and beans were an occasional supplement. A quarter of all shipping between Britain and France was for horse fodder. In 1917, when there were 436,000 horses in France, the Women's Forage Corps, which numbered 6,000 by 1918, helped in baling and transporting the hay. They stepped into the breach in much the same way as the women handling the horses at Remount Depots.

However, there were times during the war when there was a serious shortage of fodder, especially in the first winter of 1914-15 and the Retreat of March 1918.

Matters would have been better if he [the horse] had been given warm food and plenty of it, but in that first winter and often later in the war, fodder was desperately short, with no overhead hay nets; so whatever there was, was trampled into the mud or blew away. Often the poor beasts were so hungry they ate their own sodden rugs, choking to death over the buckles. Sometimes they were so desperate that they tore the epaulettes off the men's shoulders. (13)

Providing water for the horses was also very difficult in the retreats of 1914 and 1918. Gunner J W Palmer of the RFA said that on the 1914 retreat:

… the horses were more or less starved of water ... we went to various streams with our buckets, but no sooner had we got the water halfway back to them, than we moved again. We had strong feelings towards our horses. We went into the fields and beat the corn and oats out of the ears and brought them back, but that didn't save them. (14)

The horses of supply and ammunition columns struggled day and night through blasted and muddy ground that could not be negotiated by motor vehicle. The limbers and wagons made an easy target for enemy fire. The infantry could seek shelter in trenches and shell holes. Not so the horses. They were left to stand in the open, often harnessed to transport wagons or guns with no cover from shells, machine gun fire or hostile aircraft. Horse lines were deliberately targeted later in the war. Arthur Halestrap, Royal Engineers Signals Division, said that he would never forget the sound of the ‘screaming' of injured horses. (15)

Mustard gas burned and blistered their skin and irritated their eyes, and their lungs were assaulted by chlorine gas. The initial protection provided was gauze plugs inserted in the nostrils and secured with three safety pins through the nose. This was followed by a flannel nose bag that was frequently chewed, rendering it useless.

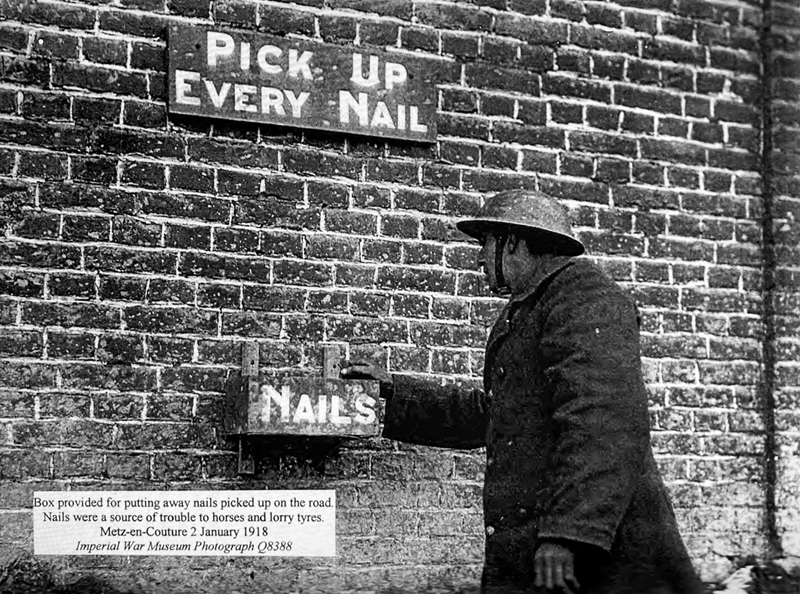

Other hazards included discarded nails from supply packing cases. These were indiscriminately scattered over the ground after the cases were burned.

From the winter of 1915-16 onwards no less than 400 cases a week were admitted to the veterinary hospitals suffering from foot injuries due to these nails, and serious efforts were made to remove the danger, but they were only partially successful, and towards the end of the war attention was directed to devising a practical metal shoe that would protect the animal's feet from the nails.(16)

With a shortage of stabling and hard standings, horses suffered from 'greasy heel' (mud fever) as a result of standing in wet and muddy conditions even when at rest; rubble overlaid with straw provided some respite. Hard standing was also made by an inventive use of bully beef tins. But not all horses survived the mud. Gunner Philip Sylvester RA remembered that at Arras in 1917 their 'horses were up to their bellies in mud':

We'd put them on a picket line between the wagon wheels at night and they'd be sunk in over their fetlocks the next day. We had to shoot quite a number. (17)

The horse was a valuable commodity and without the expertise and innovativeness of the Army Veterinary Corps, (18), the British Army would have encountered a logistical, or in the parlance of the day, an 'administrative' nightmare. The growth of the AVC was commensurate with that of the Army. There were 197 officers and 322 other ranks at the outset of war. This expanded to 1,356 officers (182 from the Colonies) and 26,146 other ranks. With the continued demand for 'A' category men at the front, low category men were sent from fighting units to increase the numbers. Lacking knowledgeable manpower, the AVC established courses in horse management. Lasting for ten days at a time, they were able to instruct 50 officers and 350 NOs each month. Schools of Farriery were set up and eventually trained 1,317 shoe smiths and farriers. But the most important part of the AVC's work was the care of injured and sick animals. A large infrastructure was set up to attend to this.

Mobile Veterinary Sections were attached to every infantry and cavalry brigade. Officers were detailed to the forward areas to tend to the needs of the injured horses, and if the injury necessitated it, to destroy the animal. Treatable animals were sent back to veterinary hospitals, either on foot or by train, horse ambulance or barge. They were identified with the serial number of the unit they were attached to, and the colour of the label indicated the required treatment. White for medical cases, green for surgical and blue for animals to be ‘cast' (destroyed). After discharge from hospital they were sent to convalescent depots. These were also a respite for tired and worn out animals. With this level of care two million horses and mules, out of the 2,562,549 that were hospitalised, were returned to duty. Horses blinded by gas or ophthalmia (a common complaint in France) were used for ploughing and agricultural purposes behind the lines to supplement the diet of troops. The AVC was also responsible for a decline in the incidence of the contagious diseases that had previously laid waste to so many animals in the Boer War. Glanders and mange were more efficiently controlled, and the mortality rate from equine pneumonia was greatly reduced.

The varied work assigned to an AVC Officer is described in the diary of Lieutenant Colonel Hubert M. Lenox-Conyngham, Reserve Army. The entry for 21 July, 1916 reads:

Inspected X Corps Heavy Battery horses - Capt. Hayter V.O. [Veterinary Officer] ic. Excellent condition - have had a few cases of mange. Then to VIll Corps Heavy Battery horses - not so good and a good deal of mange - too fond of keeping horses under suspicion [instead of sending for treatment). On August 4th 1916 he had 'lea at No.22 Vet. Hospital. Looked over Shoeing School of Instruction'. On the 12th August, 1916, he 'arranged to have water troughs disinfected regularly and more troughs provided'. The next day he 'tried new pattern 'helmet' for horses when attacked by gas.

His diary (19) continues with recommendations for ‘horse standings for the winter', and the inspection of cases of pneumonia. On 22 October 1916 he visited:

AMPLIER to see 6 horses left by the 21st Division /when they moved] and reported by ADVS (20) 37th Division as dying of starvation. Found 1 dead, 1 down and unable to get up destroyed this and ordered ADVS 31st Division to collect rest at once. These horses were left on the 17th …

On the 22nd November 1916 he:

… enquired into the case of one horse left by 2nd Aust. F.Art. 10th Bge. (21) by two men who said it was to be slaughtered & accepted money. Horse well worth treating so took it away and gave information to try and trace the men.

He was also concerned about the damage to horses feet by nails and shell splinters, and on 6 January 1917:

… inspected horses and mules shod with plate of oil drum tin [apparently to avoid the punctures made by the nails mentioned above] ... will arrange further trials.

Lieutenant Colonel Lenox-Conyngham provides an excellent example of the range of skills required by a veterinary officer, the attention to detail and the care meted out to the horses at the front.?2 By 1918, even with the increase in long distance shelling and gas, the death rate was considerably reduced by the skilful work of the AVC, and by the support given to them by the RSPCA and the Blue Cross.

At the outset of war the RSPCA's support was refused on the grounds that the AVC was capable of managing alone. This did not stop the organisation from encouraging inspectors to join the AVC and unofficially supply horse ambulances. Eventually, the Army Council relented and requested RSPCA support; an official fund was set up and it was made an auxiliary to the AVC.

Through the medium of the Society over £200,000 was voluntarily subscribed by animal lovers and expended, under official guidance on veterinary supplies. These included, amongst many other things, 180 horse ambulances, 26 motor horse ambulances, 13 complete veterinary hospitals accommodating in all 13,500 animals, horse tents, and numerous supplies such as corn and chaff cutters, electric clipping machines and body sheets. (23)

High Command seemed to be unaware of this, as according to Lenox-Conyngham's diary of 4th August 1916:

Dined with G.O.C. [General Sir Hubert Gough]. Surprised that he nor 3 other generals present had any, idea that the RSPCA were doing anything for us - (they) thought it was the Blue Cross. (24)

The Blue Cross, although not officially authorised by the War Office, provided hospitals, ambulances and supplies, and gave invaluable help to the French Army:

Indeed, the Chief of the War Cabinet, when paying a tribute to the work of the Society, asserted that it had fallen to the lot of the Blue Cross to teach the French Army the lesson of kindness to animals. (25)

The society established nine veterinary hospitals in the French lines, supplying the necessary equipment and training the surgeons and staff. Over half a million pounds was voluntarily contributed to the Society's War Fund by the British public.

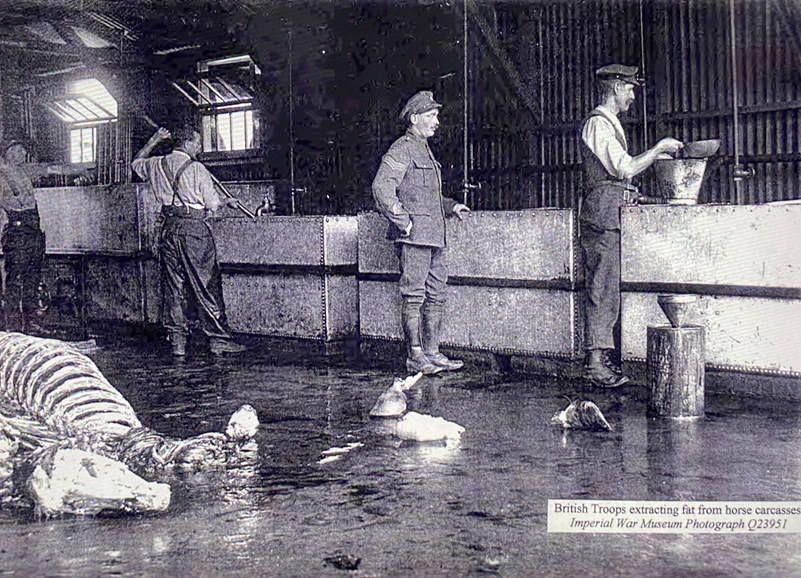

Throughout the war the carcass of dead or slaughtered horses were disposed of at Horse Carcase Economiser Plants. These were set up on the lines of communication and were humanely run by the AVC and the RSPCA, who had supplied funds for the complete installation of seven of these plants. No part of the animal was wasted. Salvage included hides, hair, hooves (for glue), bones, fat (for the glycerine needed in explosives), desiccated meat and manure. (Dung mixed with raw offal was used to produce methane gas, which was used to heat the hospitals in France). The income from these plants in one five week period was £31,000. In June 1919, old horseshoes sent to Richborough were sold for £6-5-0d a ton; hides fit for tanning £1 each, and horse hair sold for 1/3d a pound. Hooves sent to the Sheppey Glue and Chemical works were selling for £14 a ton, and dried flesh sold to the London Butcher's Hide and Skin Co. for £30 a ton. The Salvage Corps returns for September 1918 included 122,354 horse shoes and 8,880 nose bags. (26)

During the four years of unquestioning service there were moments of lightness to compete and display the animals to which they had become so attached. The divisional band played music which ranged from regimental marches to the West End hits of the day; there were riding rings, jumps, buffets and bunting. Officers put in two or three francs a head for the prize fund. Captain J C Dunn wrote in August 1915:

… a succession of officers … made conspicuous by their wearing fluttering black ribbons between the shoulders… appeared and promptly disappeared, each between his horse's ears.

There were wrestling matches from the backs of horses for the men and competitive races between quartermaster sergeants and officers; gunner NCOs rode mounts groomed to the nines " with their artillery air of "We're as good as the Cavalry any day”. (27) Dunn also noted in July 1917 that it was:

.... a great matter in these events to be on the right side of the judge. This one (the Judge] recognised Billy as having come from his brother's stable on mobilisation; so the CO. went off with a cup, and a smile as expansive as the Cheshire Cat's. (28)

Repatriation of horses began in January 1919 and during the following two months 35,000 were sent over to Tilbury, Southampton, Hull and Richborough by train and ferry. Horses from theatres of war outside France were sold locally, as the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries was opposed to their repatriation for fear of disease. By mid-March 62,000 horses were sold for 2 million pounds. The 31,667 horses still being handled by UK Remount Depots were also sold. Thousands were sold to French and Belgian farmers as working horses, at an average cost of £40 per horse. Those sold to French butchers for human food sold for an average of £20 per horse. (29)

However, not all horses were sold off. Officers were allowed to buy their mounts once they had been passed as fit to take home. David, a horse that had served in the Boer War and throughout 1914-18, was jointly purchased by four officers, and sent to a happy retirement. Two RHA gun horses, Jones and Joubert, walked straight to their old stalls at Aldershot barracks on return in 1918. They had been out since Mons. The Old Blacks, four black gun team horses, were honoured with the task of transporting the coffin of the Unknown Soldier for burial in Westminster Abbey; and two horses Nobbie and Dobbie both carried on working for Northwood and Tottenham Councils respectively. Nobbie worked for nearly thirteen years and Dobbie worked until June 1932. Both were finally retired to the Countess of Warwick's estate at Dunmow in Essex.

When the time came to go home, few of those involved with these horses of war would forget the devoted service they gave, and the sacrifice they had made for the men at the Front. We can be thankful that these remarkable animals have been honoured and now have their own memorials.

For never man had friend

More enduring to the end

Truer mate in every turn of time and tide. (30)

- My thanks go to Leslie Graham for his assistance in researching this article, and for discovering some original gems.

- Gilbert Frankau, ‘Gun-Teams', The City of Fear and other Poems, Chatto & Windus, London, 1918. Gilbert Frankau also contributed to The Wiper's Times and wrote Peter Jackson; Cigar Merchant.

- John Terraine. White Heat. The New Warfare 1914-1918. Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1982.

- Major Desmond Chapman-Huston and Major Owen Rutter. General Sir John Cowans G.C.B, G.CM.G. Vol.I. page 254-5. Hutchinson & Co. 1924.

- H&G Simonds supplied the Army with beer at Aldershot and in the Empire throughout the 20th Century. By 1950 their wines and spirits company in Gibraltar was called the 'service to the Services". They were sold to Courage in 1960. Information on Simonds Brewery supplied by Dr.K. Thomas, Archivist, S&N UK Lid.

- Secretary to the North Riding Territorial Association. He joined the Remount Service, and was later offered the job of Assistant Director of Remounts at the War Office which he turned down.

- Major Desmond Chapman-Huston and Major Owen Rutter. General Sir John Cowans G.C.B., G.C.M.G. Vol.I page 94. Hutchinson & Co,1924.

- WO 95/536.

- WO 95/536

- Army Form W 3123.

- At the outbreak of war the ASC numbered 450 Officers and just under 10,000 other ranks. The strength increased to the equivalent of 16 Divisions by the end, This was double the size of the original BEF.

- A O. Temple Clarke RA.S.C. (T.F). Transport and Sport in the Great War Period. The Garden City Press Ltd, 1938.

- Jilly Cooper. Animals in War, page 34. I.W.M 1983

- Max Arthur in association with the IWM. Forgotten Voices of the Great War, p.31. Ebury Press, London, 2002.

- In conversation with the author. Arthur Halestrap, veteran of the Great War, died April Ist 2004, aged 105.

- Peter shaw Baker. animal War Heroes. a&c black, Second edition, 1933.

- Max Arthur in association with IWM. Forgotten Voices if the Great War, p.206. enjeu press. London 2002

- The ‘Royal’ prefix was conferred on the 27 November 1918.

- WO 95/536

- Assistant Director of Veterinary Services

- Australian Field Artillery 10th Brigade.

- A leather jewellery pouch belonging to Lt. Col. Lenox-Conyngham is still in the possession of his granddaughter, the author Xandra Bingley. It is still full of bloody needles and cotton. (For stitching wounded horses).

- Peter Shaw Baker. Animal War Heroes, page 115. A&C Black Ltd., second edition, 1933.

- WO 95/536

- Animal War Heroes, page 119.

- MUN 4/5815

- RH. Mottram. The Spanish Farm Trilogy 1914-1918, p.367. Chatto & Windus, London, 1927.

- Captain J.C. Dunn The War the infantry Knew 1914-19, pages 139&367. Reprinted by Abacus, London, 1994

- Statistics throughout this piece, not otherwise credited, are from Statistics of The Military Effort of The British Empire During The Great War 1914-1920. Published by the War Office, March 1922.

- G.J. Whyte-Melville (1821-1878). "The Place Where the Old Horse Died'.