Iron Clad. The Service of 202081 Pte Frank Reece Beresford, H Bn Tank Corps by Charles Reece Beresford

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Iron Clad. The Service of 202081 Pte Frank Reece Beresford, H Bn Tank Corps by Charles Reece Beresford

[This article first appeared in Stand To! No.40 Spring 1994 (pp13-14) The entire archive of Stand To! (up to the last 12 months) is available online for Western Front Association members to browse and download].

Pte Frank Beresford

Having been turned down by the Royal Navy on account of 'defective colour vision'. Frank Beresford volunteered for service in the Machine Gun Corps. It was discovered that his knowledge of motorcycles was slight and he was encouraged to gain experience. This consisted of riding a James two-stroke near his home in Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent and, on 10 November 1916 he reported to Belton Park in Grantham where he met the vastly different Indian machines with which however he never had to grapple. The eighteen-year old was transferred to the MGC Heavy Section's Tank Corps training depot at Bovington, Dorset. Ironically, some time was spent with the Royal Navy at the gunnery school on Whale Island, Portsmouth.

After months of training he left Southampton aboard the Londonderry and arrived in Le Havre in the early hours of Wednesday 22 August 1917, moving at the end of the week to Blangy-sur-Ternoise and three weeks later to Wailly. On the last day of the month a British aeroplane crashed into a tree on the site but the pilot was unharmed. The camp was shelled the next day and the cook, W. Jones, was killed. The unit left on Friday 5 October and moved to Ouderdom in Belgium for the unpleasant posting in the Salient, mainly at Voormezele and Dikkebus. This was of course during the period of Third Ypres and Flanders mud was totally unsuitable for heavy armour. Passchendaele was taken at the beginning of November. H. Battalion then moved SE of Albert to Bray on the Somme.

Here, preparations were being made for the battle which was to begin on 20 November, the most memorable day in the annals of British Tank history and which was to become the celebrated anniversary thereafter throughout the Royal Tank Regiment. During the 18-19 November Pte Beresford was in Dessart Wood near Havrincourt and the Battle of Cambrai stated at dawn on the 20th. It has been described in detail by military historians but the ever-remaining personal impression was of the remarkable still quite which preceded the intensity of sound when action began. E Battalion suffered heavy losses on the second day. The action continued for H Battalion during the following days with an enforced pause, owing to fuel shortage, from the evening of the 27th until next morning. Thursday 29th was a 'rest' day at Fins near Gouzeaucourt but action recommended on 1 December until the tanks finally left Fins on the 6th to return to Bray. During the battle, H Battalion had been temporarily attached to 71st Infantry Brigade, 6th Division and was supporting the 1st Battalion The Leicestershire Regiment. In most of the books listed in the references may be seen a classic photograph from the Imperial War Museum showing ‘Hyacinth’ (ie H Battalion) ditched at Flesquieres Ridge and Frank Beresford (in the trench?) was able to name a number of those in the picture when he saw it for the first time, many years later.

Activity varied thenceforth, with a hectic period during March 1918 in the German spring offensive (‘Kaiserschlacht’), with FI Battalion in the thick of it, particularly on tire 23rd. The life became quieter. Frank was in Blangy in April and Humieres. Erin (near St. Pol) and Poulainville early in May.

The pictures which appeared in Stand To! numbers 26 and 28 show the workshops and stores at Erin with which he would be familiar, and the photograph of King George V watching a demonstration near there includes Maj. General Elies (commanding Tank Corps) whom Frank met at reunions in the 1930s.

However, on Sunday 19 May 1918, somewhere between Buire, Bray and Daours, south of the Amiens— Albert road where the Ancre meets the Somme. Frank was wounded by German shell fire. His friend Walter Kelly (after the war, a manager of the Dewhurst shop in Hull) missed him, made a search and found the casualty who was then attended to by Canadian RAMC. It was 'a Blighty one' which for the rest of the year kept him in hospital in Sidcup in Kent and in a converted school in Stanford Road, Thornton Heath. The War Diary also names two officers and fifteen other ranks wounded by gas the following day. Frank's entries give errors in his army number and month of wounding.

Plastic surgery was in its infancy and a piece of jagged German steel, a family memento, was removed from the tongue. It weighs 9.38 grammes and is 3.3 by 1.1 by 0.7 centimetres approximately. The shattered mandible was sewn with silver wire to the upper jaw acting as a splint. All the patients had facial injuries and many took their nourishment fluidly and noisily via a tube. The consultant surgeon was Harold Gillies (knighted in 1930), older cousin and mentor of Sir Archibald Mclndoe who was to undertake similar work, especially on airmen with severe bums, particularly to the hands and face, in the Second World War. Both were New Zealanders of Scottish stock. Sir Harold Delf Gillies (called Giles) left Dunedin to study medicine at Caius, Cambridge and ENT surgery at St. Bartholomews, London. As Captain RAMC, he joined the unit of Sir William Arbuthnot Lane at Aldershot when thirty-four years old, devised the ‘tubed pedicle’ graft and subsequently wrote The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery, spending many years after the Armistice working on the repair of war wounds at Sidcup. His expertise was invaluable in the 1939-45 Second World War also.

Frank Beresford often reminisced of the time at Sidcup when, 'coming round' after surgery, he was startled by the vision of a horribly burned face leaning over his bed. It turned out to be a sailor who had been badly injured at Jutland, Able Seaman Vicarage. His face was being rebuilt by Gillies and he managed to sing, frequently, the popular 'Roses of Picardy'. Frank said that he could see the burned face thereafter whenever he heard the melody.

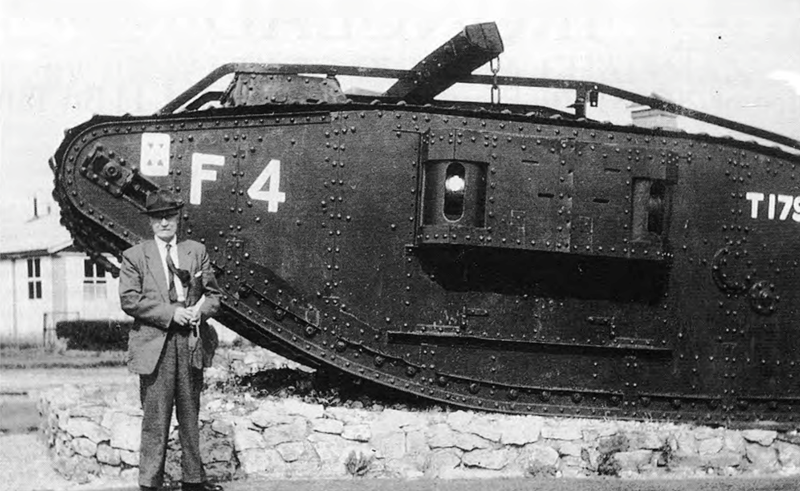

Frank Beresford visiting Bovington Tank Museum in 1960

Other members of the family recall his home leaves in hospital blue and he was in London, returning to hospital, on Armistice day. Following his discharge, he returned to the family transport business in Stoke-onTrent. His son, daughter-in-law and granddaughters remember the scars he carried until his death almost exactly sixty-one years after Cambrai.

REFERENCES

Beresford, Frank Reece: Personal diary and reminiscences.

Blaxland, Gregory: Amiens: 1918.

Cooper, Bryan: The Ironclads of Cambrai.

Pitt, Barrie: 1918 The Last Act.

Hart, B. H. Liddell: The Tanks. Vol. I.

‘J.F.R.H.’ (ed.): Short History of the Royal Tank Corps.

McLeave, Hugh: Mclndoe, Plastic Surgeon.

War Diary, Public Records Office.

Warner, Philip: Passchendaele.

Woolcombe, Robert: The First Tank Battle.

Wylly, H. C: History of the 1st and 2nd Battalions The Leicestershire Regiment in the Great War.