James VII and James VIII: Two outstanding officers

In a footnote in the History of the 62nd (West Riding) Division, written by Everard Wyrall, there is a passage which quotes the GOC of the Division (Sir Walter Braithwaite) as follows:

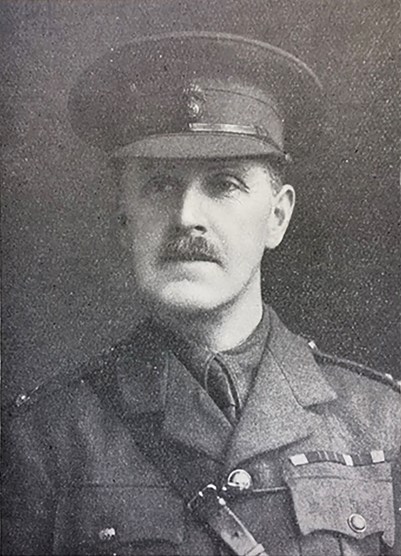

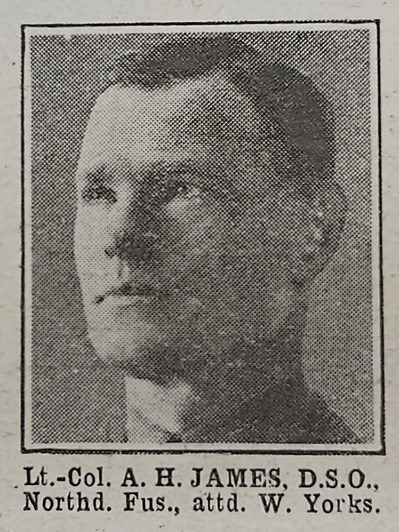

“I would also like to say something about Lieut-Colonel AH James of the 8th West Yorkshires, known throughout the division as ‘James VIII’ in contradistinction to his namesake Lieut-Colonel CK James who commanded the 7th West Yorks, and who was known as ‘James VII’. The division sustained a very great loss in the death of James VIII during this period [March 1918]. He was killed as he would have wished to be killed – in command of his regiment….His loss was felt not only in his battalion, but in his Brigade and throughout the Division. He has brought his battalion to a high pitch of efficiency. He was a very gallant, honest and fearless soldier, one we could ill afford to lose…”

Although the passage is mainly about James VIII, it seemed worthwhile to dig into the stories of James VII and James VIII, and the following is an account of their lives, service and death in the Great War.

Rarely can it be the case that pre-war civilians ascended through the ranks from Second Lieutenant to acting/temporary Brigadier-General during the course of the Great War. There must be even fewer instances of this happening to two officers who not only served in the same division, but also in the same infantry brigade.

In this article we will look at two men, both of whom rose from subalterns to the rank of Temporary Lieutenant Colonel and both commanded battalions of the same territorial regiment within the same infantry brigade. Both these battalions were designated ‘The Leeds Rifles’. The two officers also briefly stood in as Brigadier General. But the strangest coincidence is that both of these men had the same surname.

Charles Kenneth James: early life and war service from 1914 to March 1917

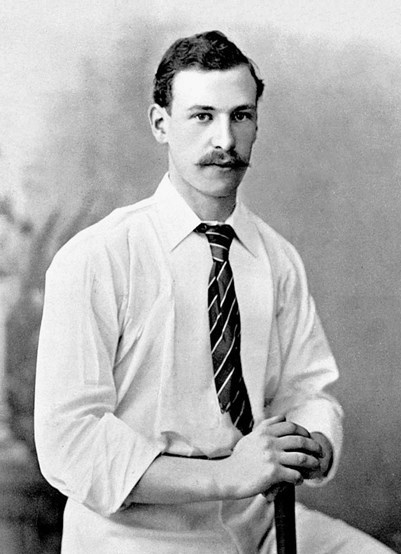

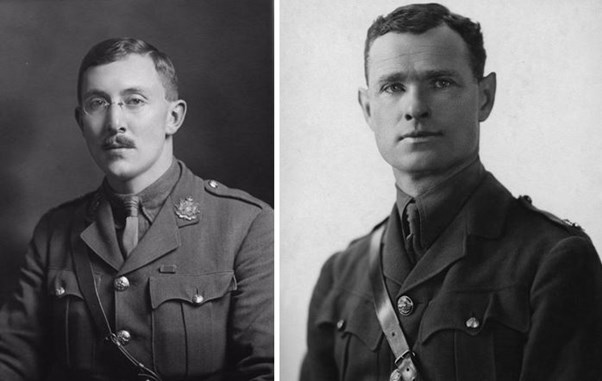

Charles Kenneth James was born in Stamford Hill, London on 19 January 1892.

One of three children, he had younger sister (Audrey Trevenen James) and an older brother Baron Trevenen James who was to be killed in 1915 whilst serving in the RFC.[i] Charles was educated at the School of Messrs Innes-Hopkins, and Mr Broadrick’s School, Harrow. He later went to Cheltenham College in 1905, prior to going up to Caius College, Cambridge in 1910.

Whilst at Cambridge he joined the Officers Training Corps and this no doubt put him in a good position for his later commission in the Border Regiment on the outbreak of war.

Having originally intended to join the Indian Civil Service, Charles had been accepted for service in the Royal Navy but was later rejected due to defective eyesight. During two long vacations Charles went to Russia, where he coached Alexi, (Alexander Wilhelm Freiherr Staël von Holstein) the only son of Baron Stael von Holstein, Agent and Steward to the Grand Duke Peter of Russia. In addition to being a fluent speaker of Russian, Charles also learned several other languages.

Prior to the Great War, Charles was employed by the Asiatic Petroleum Company at Shanghai, and had served as a trooper in the Shanghai Light Horse.

At the commencement of hostilities he headed back home via Siberia, but was arrested twice in Sweden although he managed to escape after two days' imprisonment with the help of an English Petty Officer.

He arrived back in England with only 5 shillings to his name and looked much worn out.

Charles was gazetted as a Second Lieutenant in the 6th (Service) Battalion, Border Regiment in October 1914. His attestation papers tell us that he asked to join the infantry, or alternatively serve as an interpreter (he could speak fluent French, German and Russian).

By March 1915 he was a full Lieutenant and in August, a Captain and Adjutant of his battalion, which was soon to be dispatched for Gallipoli as part of the 11th (Northern) Division.

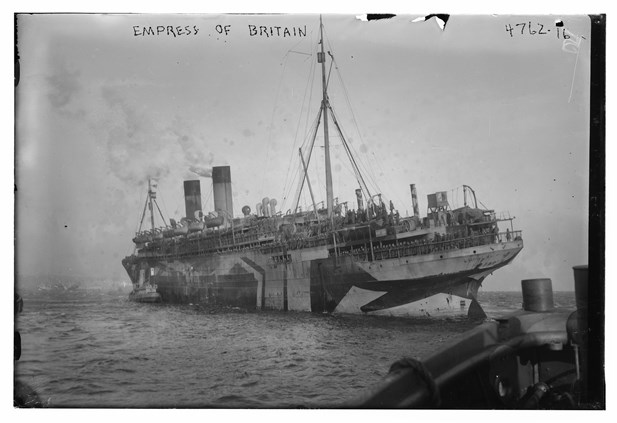

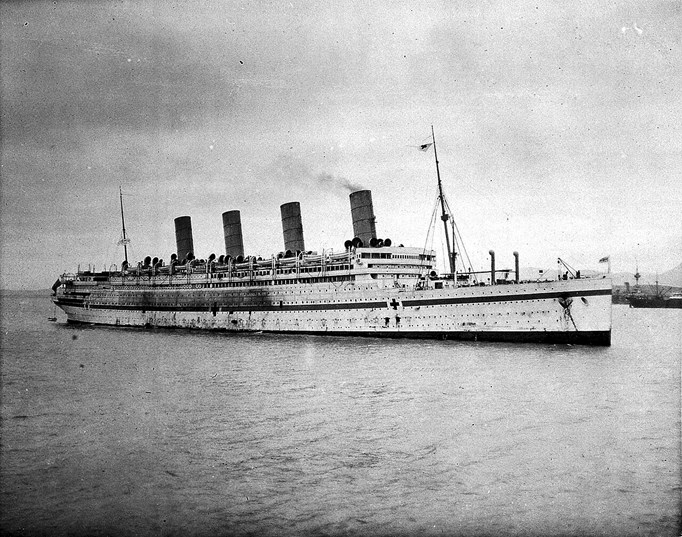

The battalion sailed from Liverpool on Empress of Britain

The 6th Borders first landed at Helles on 21 July (via the beached River Clyde) where they provided carrying parties before going into the front line on either side of Achi Baba Nullah. In this period they lost two other ranks wounded on 21 July and another two fatalities on 23 July. After a few days they were relieved and went to a rest camp on 30 July. From there they were withdrawn from the peninsula and went to Imbros on 31 July.

Curiously the service file for Charles suggests he received bomb wounds to his legs on 30 July, this (if dated correctly) was when the battalion was being relieved in the Helles sector and on their way to the rest camp. Although the wounds in the telegram to his parents (which were to his ankles and thigh) were described as being ‘slight’, he was evacuated to Alexandria, Egypt where he was admitted to the 15th General Hospital. He was to rejoin the battalion on 21 September (he is mentioned in the battalion war diary as returning after being wounded). However, in the de Ruvigny roll of honour it suggests he was wounded at Anafarta: if this is the case this may have been a later wounding. The injury he sustained in July – although it may not have seemed so at the time – was a massive slice of luck and likely saved his life.

Without Charles, who was in hospital, the 6th Borders embarked for Suvla Bay on 6th August and landed at 'B' Beach. Casualties from shelling were modest with one killed and 22 wounded. The battalion then moved forward and the next day, 7th August, and took part in the attack on Chocolate Hill.

On 9th August they advanced for an attack but came under fire from Scimitar Hill. 'A' and 'B' companies suffered heavy casualties – all officers except one being killed. A roll call at dawn 10th August showed the survivors numbered just 5 officers and 120 other ranks.[ii] An examination of the CWGC records tells us that the 6th Borders lost 136 men killed on 9 August 1915.

After being wounded he was again out of action between 1 November and 12 December when he left the battalion due to sickness. He was admitted to hospital in Malta in this period suffering from pyrexia.[iii]

Charles is again noted as rejoining the 6th Borders on 10 January 1916, by which time the battalion had left Gallipoli, being first sent to Imbros (where they had arrived on 20 December) and some weeks later, on 1 February, the entire battalion arrived in Alexandria.

Charles went to France with his unit, arriving in Marseilles on 6 July 1916. The battalion arrived (after a two-day train journey) in the Arras sector for a spell of trench experience where they spent the rest of July and the whole of August. Charles is mentioned in the battalion war diary on 12 August when he and Lt Montmorency reconnoitred the wire ‘along our front’.

The battalion was involved in an attack on 13 September 1916 at Ovillers. Charles was awarded the DSO (along with the battalion commander, Lt Col Mathers) for “having led a party against the enemy with greatest courage and skill and put the enemy to flight. Later he organised and led a bombing party, capturing a much greater position than he had set out to take. He has on many previous occasions done very fine work.”[iv]

Charles was able to obtain leave in late October 1916 but was then back with his battalion for the rest of the year. On 27 December 1916, due to the battalion’s Commanding Officer taking command of the Brigade, Charles was given temporary command of the battalion. At that point he was detailed as ‘Major’. He was again able to obtain leave in late January 1917.

The war diary entry for the end of January 1917 details Charles being mentioned in despatches and also confirms the promotion (referencing the London Gazette) to Major with effect from 21 November 1916.

The last entry referencing Charles in the war diary of the 6th Borders was that in March, when it states that “Major CK James, DSO left the battalion on 11 March to command the 2/7th West Yorkshire Regiment.”

Rarely can someone have been promoted so quickly from Second Lieutenant to Lt-Colonel within 29 months of joining the army, and have been awarded the DSO as well.

Archibald Hugh James

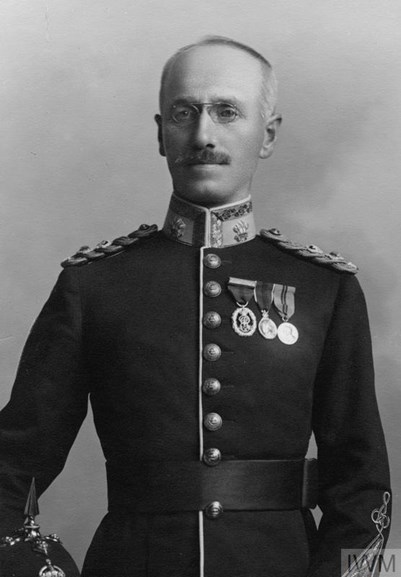

‘Archie’ as he was known was born on 8 November 1877 in India. He was one of four sons of William Edward and Anabella Emily James.

His father worked for the Indian Civil Service but on inheriting Barrock Park (the family home just south of Carlisle in Cumbria) took his family back to England.

However William then decided to get his full pension but to gain this he would go back to India for a while. Unfortunately whilst back in India he was bitten by a rabid dog. Family legend has it that William asked a friend to smother him with a pillow before the symptoms became too bad. William died when Archie was six years old.

His widow (known by her middle name of Emily), returned to England but could not afford to educate six children whilst living at Barrock Park which required quite a large staff, so she took a house in Clifton, Bristol and Archie and his brothers went to Clifton College as day boys.

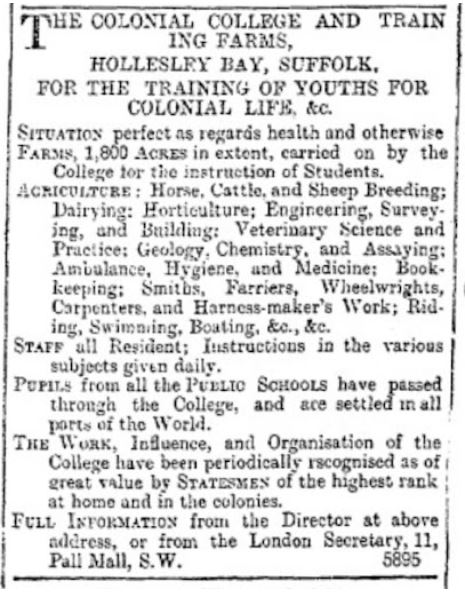

After Clifton College, the two older brothers joined the Army and the younger brother joined the Royal Navy but Archie turned his back on the military and went to Hollesley Bay College in Suffolk to study agriculture.

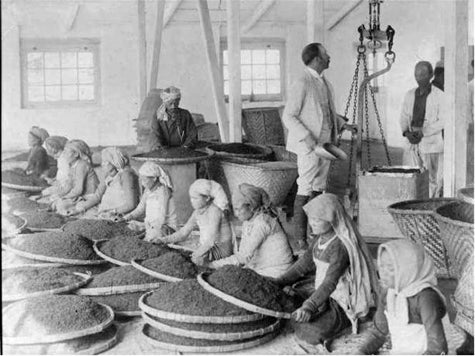

The college existed to train those who planned to emigrate in stock raising and agriculture. He followed his vocation by going out to India to join his Uncle Evan and worked as a manager of a tea plantation in Darjeeling.

Whilst in India he joined the Northern Bengal Mounted Rifles – a corps comprised almost entirely of tea planters - as a private and learned local languages, but refused the offer of a commission in the regiment. He served in the unit for 12 years.

Archie inherited money from a relation in about 1910, which enabled him to retire early back in England. Subsequently, after visiting East Africa, Archie returned to the UK and was home on the outbreak of the war when he applied for a commission and was gazetted as a temporary Lieutenant in the 8th (Service) Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers.

Promoted to Captain, he sailed for Gallipoli on 3 July 1915 with the battalion (as with Charles James this was part of the 11th (Northern) Division) on board the large liner the SS Aquitania.

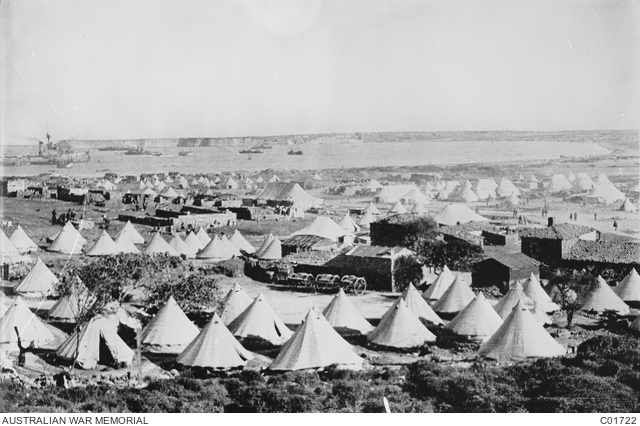

On the first morning after departing Liverpool the battalion war diary notes the Aquitania was attacked by a submarine, but fortunately the torpedo missed. The passage through to the peninsula was rapid – they arrived in Mudros Bay on the island of Lemnos on 10 July and were at Kephalos Camp for several weeks.

On 6 August the 8th Northumberland Fusiliers embarked for Suvla Bay. It seems that Archie was wounded in the advance an Anafarta Sagir and evacuated to Lemnos where he wrote home to his Uncle (who had been knighted and was now Sir Evan James) describing what had happened to him.

Archie had been wounded in the chest, but the bullet had passed through his field glasses – which he had been holding – and then hit his steel whistle thus saving his life.

After recovering from his wounds he returned to his battalion on the peninsula. On the crossing to Gallipoli from Lemnos one of the fellow passengers was the brigade commander, Brig-General F F Hill who Archie found to be “very civil” and was “all there”.

Archie must have made an impression as he was invited to be Hill’s guest at brigade HQ but later – on joining his unit - found only two of the original officers still with the battalion.

Given command of ‘Y’ Company of the 8th Northumberland Fusiliers, Archie James continued to serve on the peninsula. He wrote to his Uncle Evan numerous times, including one letter at the end of November about enduring a storm, in which he says nine men of the battalion were killed.

After evacuation, the 8th Northumberland Fusiliers, with Archie still as OC ‘Y’ Company, found themselves back on Imbros – from where they had departed back in August. In a letter to his uncle he states his belief that he was the last man to leave the peninsula.

By early February the battalion was in Egypt “digging trenches a full eight hours a day”. Within a month he heard that his mother, Emily, had passed away. In May he wrote about a heat wave – sheltering in his tent, the temperature was clocked at 117 degrees (47 degrees Celsius).

Along with the rest of the 11th (Northern) Division, and on a parallel course to his namesake Charles James, he landed in Marseilles in July 1916 and before the end of the month had been promoted to Major and second in command of the battalion. During an attack on the Somme at the end of September, the Commanding Officer (Lt Colonel CE Fishbourne) was wounded by a shell (confusingly, Archie wrote that he was ‘killed’ but later found out that he was still alive, although wounded)

Fishbourne succumbed to his wounds on 6 October (being buried in St Sever Cemetery, Rouen) and as a result Archie assumed command.

On 7 October he wrote again to his uncle saying how the Corps Commander (probably Sir Claud Jacob) addressed the battalion and told us how very proud he was of us. “He also told me that he thought it very remarkable my commanding the battalion, and being a major, and not being a regular.”

A week after this letter was sent, on 16 October, Major Ford of the 6 York & Lancs joined and assumed command in place of Archie. A month later, on 29 November the battalion war diary noted that Major AH James left the battalion for temporary command of the 7th Royal Warwicks. Returning on 10 December he was in command of the battalion when the new CO (Ford) was on leave. In the New Year – on 22 January – Archie was again loaned out, this time to take temporary command of the 5th Dorsets, rejoining the battalion on 13 February.

He wrote “It’s a great bore these temporary commands, and I wish to goodness they would not shunt me about. But one has to do what one is told, and I suppose the experience will be useful”.

Another temporary command appointment (to the Glosters) took place in mid February.

On 26 February the battalion was attached to the 62nd Division and less than a week later, the battalion war diary notes that Major AH James left to command the 2/8th West Yorks.

Promotion and to 185 Brigade

The 62nd (West Riding) Division was a second line Territorial division which had been held in the UK until the very end of 1916, arriving in France in early January 1917.[v] The division contained three infantry brigades: 185 was made up of four battalions of the West Yorkshire Regiment; 186 comprised four battalions of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and 187 Brigade had two battalions of KOYLI and two Y&L battalions.

Within 185 Brigade, the four West Yorkshire Regiment battalions were 2/5th, 2/6th 2/7th and 2/8th. The latter two were known as the 'Leeds Rifles'.

The 185 Brigade’s Battalion commanders whilst in the UK were as follows

2/5th West Yorks Lt Col John Josselyn

2/6th West Yorks Lt Col John Hastings

2/7th West Yorks Lt Col Francis Stanley Jackson[vi]

2/8th West Yorks Lt Col William Hepworth

Things did not start well for the 62nd (West Riding) Division. Put into the line, in the moonscape of the northern Somme battlefield, in extremely trying conditions with snow blanketing the ground, posts were manned and relieving troops lost their way.

It is possible that this had the effect of prompting the GOC of 62nd Division (Major General Sir Walter Braithwaite) to make some changes in those who command the Leeds Rifles.

In the 2/8th West Yorks, Lt Colonel Hepworth (who was 53 years of age and had served in the Boer War) was replaced on 22 February by the 33 year old Robert Essington Negus, who was up to that point a Major in the 2/6th Duke of Wellington’s regiment (in the 62nd). But only days after assuming command, Negus was wounded. It is because of this that Archibald James (aged 39) was appointed to command the battalion.

Archie says in a letter home that he took over because the previous CO had been killed. But this is not true, the 2/8th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment war diary says “Major RE Negus wounded on 26 February”. Archie arrived to command the battalion on 28 February 1917.

In a letter home, Archie describes an incident that must have taken place less than a week of taking command. He wrote (to his Uncle Evan) “I rushed up [to join the battalion] in a great hurry. The dug-out I first visited had this message left in it [by the Germans, who had pulled back to the Hindenburg Line in the late winter of 1917] Dear Tommy, I hope you will enjoy your stay here. In a few minutes you will be blown to hell. [looking aound, we] found 100lbs of dynamite fused and detonated, by a stove. In the next dug-out I occupied there was a piano with a lot of bombs arranged inside it but they didn’t explode….I had a narrow shave yesterday [this was possibly 5 March] … I went out to reconnoiter the outpost line….I hoped that owing to the haze the enemy would not spot me, but a sniper got on to us and had eight shots, the last one of which got my orderly clean through the shoulder.” In a subsequent letter, he says the orderly died of his wounds [it has not been possible to positively identify the orderly in question, as three men of the battalion died around this date].

As mentioned above, Archie took command of the 2/8th West Yorks on 28 February. Over in the 2/7th battalion, Lt Col FS Jackson (who was aged 46) proceeded to hospital sick on 1 March,[vii] on the same day, Captain GW (Geoffrey Walter) Lawson arrived from the 2/5th Y&L to assume role of second in command,[viii] and Major OC Watson (of the 2/5th KOYLI) [later to be awarded the VC] arrived to take temporary command. Watson soon handed over to the new commanding officer Charles Kenneth James who arrived on 11 March 1917, only weeks after his 25th birthday. He had been in France only seven months and now found himself in command of a battalion.

So, by the middle of March both battalions of the Leeds Rifles (2/7th and 2/8th West Yorkshire Regiment) - newly arrived in France and about to prepare for the difficulties of trench warfare - had new commanding officers, both of whom had gained experience in Gallipoli and in the later stages of the Somme campaign. If they had not met during their time with the 11th (Northern) Division, it is certain that they were to see a lot of each other over coming months.

1917 and early 1918 – Three battles and Line Holding

It seems that Archie soon had a bit of a clear-out of a number of the officers. The 2/8th battalion war diary reports “Major ND Lupton [Norman Darnton Lupton] assumed duties of 2i/c” on 18 March 1917 and Captain GR Newitt assumed command of A Coy.

On 25 March Archie James – despite only just taking over his battalion - took temporary command of 185 Brigade as Brigadier General de Falbe was on leave (Major Lupton took command of the battalion).

Writing home of this, Archie said “Such a joke, I am now commanding a brigade! The Brigadier General has gone home on sick leave and I am acting for him in spite of being junior colonel. I am quite unfitted for the responsibility, and wish to goodness they would leave me alone.”

The explanation for a temporary promotion from one of the battalions in the brigade can be found in the Brigade War diary, when it details, on 24 March, that Brigadier General de Falbe went on sick leave “as he had been suffering from Bronchitis for several days. Lt Col AH James assumed temporary command of the brigade.”

During his stint as acting/temporary Brigadier General, the brigade war diary on 29 March states “Lt Col James and Brigade Major reconnoitred proposed defensive line”.

The Brigade Major mentioned here was Richard O’Connor who was to become a successful and famous General in the Second World War.

Coincidentally, Archie may have been surprised to bump into Brigadier General Felix Frederic Hill who commanded 186 Brigade in the same division. Hill, who Archie had travelled with across to Gallipoli back in 1915 and at the time commanded 31st Brigade in the 10th (Irish) Division, had been evacuated from Gallipoli on 22nd August 1915, suffering from acute dysentery.

On 4 April de Falbe returned and took over from Archie who went back to the 2/8th West Yorks.

Bullecourt

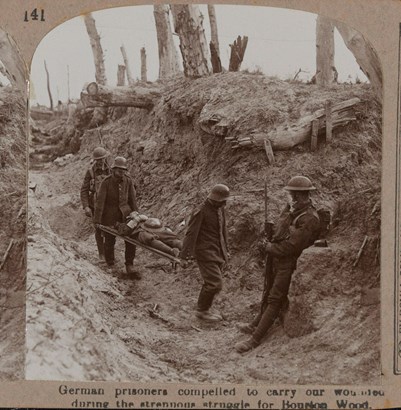

An account of the Battle of Bullecourt is outside the scope of this article, but briefly, between the April and May engagements at Bullecourt there was intensive preparation for a further attack. Despite the strength of the Bullecourt position Archie’s men were “loaned” to 186 Brigade, meaning that 185 Brigade would attack with only 3 battalions. One company of the 2/8th was then taken away as a carrying party so it was a much reduced battalion that followed 2/4th and 2/7th Duke of Wellington's into the wire and were subsequently ejected from their positions south and south west of Bullecourt. From Archie’s point of view this must have been very frustrating. His battalion was split up and posted to one side with no opportunity to play a role in the command of the battle. Communications were very poor and HQs a long way back so most of the time during the fighting was spent waiting for messages or wounded to report what was going on.

After the rigours of Bullecourt, Archie remarked in a letter home written in June “Leave has started again, but I am letting others go first though as a matter of fact all my officers have been in England since I have.” In due course he requested home leave which was endorsed by Major General Braithwaite who said “This is one of my best commanding officers. He really needs a rest. I therefore strongly recommend him for the leave he applies for”. It is not clear who had to authorise the leave, but it seems Braithwaite’s (the GOC’s) approval was needed. However, Archie’s home leave was not available straight away as on 4 July Brigadier-General de Falbe went on leave and Archie took temporary command of brigade for the second time.

On 11th July, during his time acting as Brigadier, Lt Col John H Hastings DSO “to the general regret of his battalion”[ix] was replaced as CO of the 2/6th West Yorks.

This would of course have been planned prior to Archie taking temporary command of the brigade. Hastings was appointed Area Commandant, Arras, and was succeeded by Lieut.-Colonel Charles Hervey Hoare.[x]

On 16 July de Falbe returned from leave and two days later we see from the battalion war diary that Lt Col AH James went on one month’s leave [and] Major ND Lupton took command.

On 21 August Archie returned from leave and was back in command of his battalion. It is also significant that on the same day as Archie returned home, the Brigade acquired a new Brigadier when Brig.-General Viscount Hampden took over command from Brig.-General V. W. de Falbe, who was invalided home. Hampden was aged 48.[xi]

On 10 September Archie again left the battalion in order to attend a senior officer’s course. Lupton once again assumed command of the 2/8th West Yorks. Archie’s course lasted ten days and he was back with his men on 20 September. Fortunately the 62nd (West Riding) division was not destined to see any action at Third Ypres, instead they spent the summer months in the line between Bapaume and Arras.

On 23rd September, in yet another change to the officers commanding battalions in the 185 Brigade, Captain (Acting-Major) Richard Henry Waddy, 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry, assumed command of the 2/5th West Yorkshire Regiment in place of Lieut.-Colonel J. Josselyn, who returned to England invalided for shell-shock.

At around this time, it seems Archie had a ‘joy flight’ in a Bristol Fighter (it is unclear if this was simply ‘for fun’ or if there was a serious purpose). He wrote to his uncle “My pilot insisted on doing all sorts of ‘stunts’ in the air, which nearly made me sick. Otherwise I enjoyed it. When we nose-dived we were doing 160 miles an hour. Another day I had a ride in a tank over all sorts of obstacles. It was interesting, but I have no desire to join the Tank Corps!”

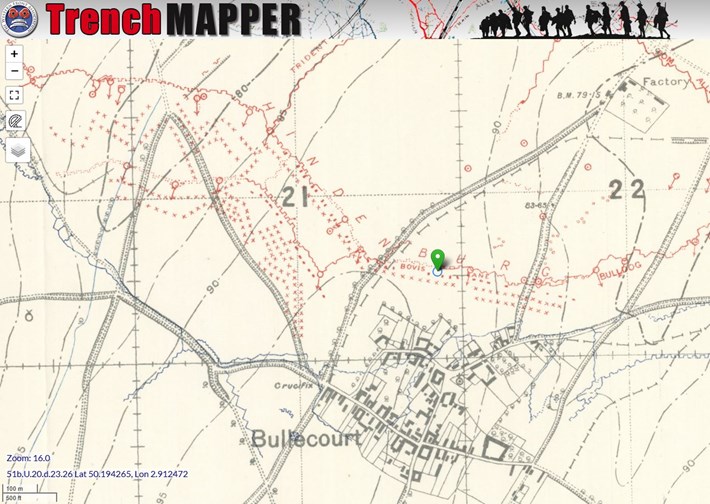

On 6 October, the battalion war diary states that the 2/8th West Yorks were chosen to carry out a raid at a later date; three days later the raid was carried out on Bovis Trench.

It appears that the raid was unsuccessful due to wire being insufficiently cut and enemy ready on account of wire cutting activities. Sgt Matthews was killed and one man was missing. 18 were wounded.

Archie in a letter says he did not accompany the raiding party,”…the only personal fighting I have done lately was to snipe some Bosche just after dawn who were foolish enough to be walking about outside their trench.”

On 15 September we read in the war diary that the commanding officer (Archie) “lectured to all officers and free[?] ranks on the war up to the First Battle of Ypres and the present Ypres offensive at 5.30pm.” It is interesting that even during the war, presentations were taking place about the recent history of the battles. Something The Western Front Association is clearly proud to continue to this day !

Over in 186 Brigade, Brig General Hill (Archie’s old friend from Gallipoli) was replaced in November 1917 by the very young Roland Boys Bradford. This event is detailed on 10 November in the 186th Infantry Brigade war diary which reads “Brigadier Brigadier General RB Bradford VC MC took over command of the 186th Infantry Brigade from Brigadier General FF Hill CB CMG DSO who retires on account of age restrictions”. Bradford therefore became, by some margin, the youngest to hold the rank of Brigadier General. He was 25 years old.[xii]

Cambrai

Archie left a detailed account of the battalion’s involvement at Cambrai on 20 November which states “My battalion was one of the two assaulting battalions of the brigade to storm the Hindenburg Line… we reached our objectives with the loss of three officers and 94 men. I took up my headquarters in an officer’s dugout [ie German dugout] – the lamp was lit and his breakfast on the table, but untouched! He left a beautiful helmet behind him, which I am giving to Lady H our Brigadier’s wife on behalf of the battalion….[xiii] It was a great day for the Division, we made a record advance of 7,000 yards, took 37 guns and over 2,000 prisoners.”

A few days later the battalion was in action again – this was the 27 November: “I was drawn into the battle at 11.30am, being told to make sure of some high ground, which we did successfully. The shelling was terrific.”

Again, a detailed description of the Battle of Cambrai is not suitable for inclusion in this piece, but in summary the situation was now very confused as the Germans struggled to contain the advance and the British tried to exploit their break in. Stationing himself at the Sugar Factory on the Bapaume – Cambrai road Archie managed intense, confused fighting, units failing to move, units breaking and falling back, patrols skirmishing in the night - sometimes immediately around his HQ.

He took overall command in the sector between the canal and the wood and manoeuvred companies from both 185 Brigade and 187 Brigade to resist the counterattacks. Sadly, unbeknown to him, he was opposite a gap in the German defences which they were covering with patrols and a few composite platoons, a gap which, once closed, shielded Bourlon Village from capture.

On 12 December 1917 the brigadier (Hampden) assumed temporary command of 62nd Division during the absence on leave of the GOC. As a result we read that "Lt Col AH James … assumed temporary command of the brigade." This was his third stint in command of the 185 Brigade.

We learn from the 185 Brigade war diary that on Boxing Day the brigadier “proceeded on leave to England.” Although there’s no mention of who took over, Archie was clearly again temporarily in charge as he signed war diary at end of month. Although this could be counted as his fourth period, as it was probably concurrent to the earlier stint, this has not been counted as a different period in charge, but given Hampden returned from leave on 9 January 1918, this period in charge of the brigade was a long one, lasting three days short of a full month.

On 1 January 1918 Archie was awarded DSO, which was awarded for his services over the previous months. However in the way that buses often come together, he was awarded a bar to his DSO within a few weeks. This second award being an ‘immediate’ award granted due to his bravery and leadership during the Battle of Cambrai. This bar to the DSO being recommended by Brigadier Hampden was formally awarded in mid February. The citation for this second DSO reads as follows:

“For gallant conduct and exceptional ability in the handling of the troops under his command on 22 November 1917, South West of Bourlon Wood and 27 November in Bourlon Wood. On 22 November the enemy attacked strongly and after sharp fighting forced his way through a gap in our defences as far as battalion headquarters. Owing, however, in great measure to Col James’s grasp of the situation and his personal efforts the troops under his command were rallied and, counterattacking, re-established themselves in their original line. On 27 November, after the failure of our troops to take Bourlon village, the situation was reported as critical, and Col James, on his own initiative, took his battalion up to the wood and made himself a personal reconnaissance, reporting to me [ie Hampden], thereby clearing up what until then had been a very obscure state of affairs. This reconnaissance was carried out under heavy enemy and machine-gun fire.”

During the Cambrai action he had been badly gassed and it was recommended he should take leave in the South of France for a ‘change of air’ but declined to do so saying he wished to remain with his regiment. Nevertheless in January he was given two weeks home leave but this was cut short due to a reorganization of battalions that was taking place.

Despite his experience and the obvious high regard he was held in, the reorganisation of the infantry battalions in early 1918 caused Archie some worry. With the reduction of battalions in a brigade from four to three, it was inevitable that many battalions would be disbanded or merged. So it was that two battalions of the Leeds Rifles (1/8th West Yorks in 49th (West Riding) Division and 2/8th West Yorks in the 62nd (West Riding) Division) were destined to be merged. This left the command of the unit in the hands of GHQ. Archie reflected on this in a letter home on 31 January 1918:

“Very likely I may find myself in a few days a major with no battalion! The Brigade and Division are doing all they can for me, and have specially applied for me, but it is all in the hands of GHQ.”

He need not have worried; he retained command of the battalion, which was – following the merger – known at the 8th West Yorkshires.

The commanding officer of the 1/8th battalion, Major (acting Lt Col) T Longbottom, came across to the 62nd Division with a number of his officers to reinforce the 8th battalion.

On 9 February 1918 we learn from the brigade war diary that Lt Col James took over temporary command of the brigade. This due to the Brigadier going on a course at Camiers. It was the fourth – and was to prove to be his last - period in temporary command of the brigade. This time he only took command of the brigade for three days. Major Longbottom was now second in command of the battalion, no doubt to Lupton’s annoyance, and therefore would have stood in for Archie whilst he was at Brigade Headquarters.

Archie’s last letter home was dated 21 March 1918. This was of course the day of the opening of the German Spring offensive. At the time the division was at Roclincourt, near Arras and therefore not in the ‘eye of the storm’ of Operation Michael. However Archie must have realised a crisis was at hand, writing home:

“I have not written before as I’ve been too worried and busy. We have been through a very trying time, and the poor battalion has suffered…. I have personally had some very narrow shaves….for the next fortnight I shall be very anxious, but will write when I have time.”

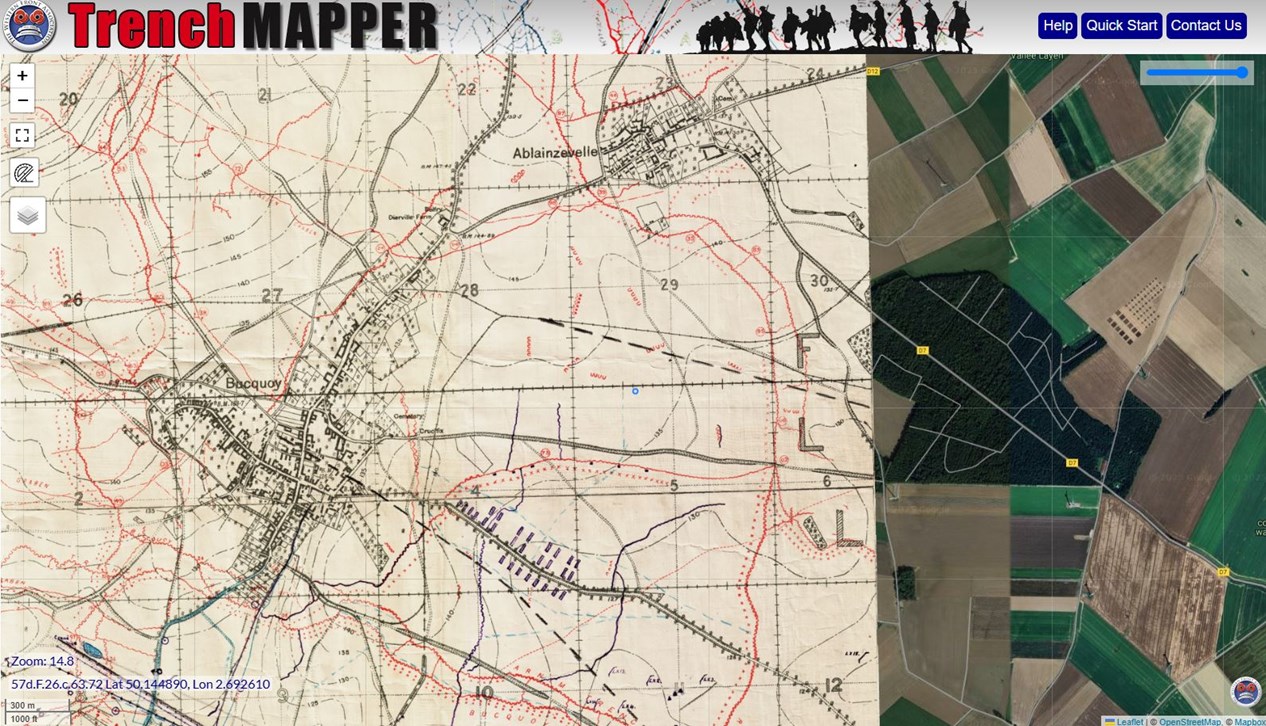

On 25 March the brigade war diary describes how the battalions (three battalions in brigade now as 2/6th had been disbanded) were ordered to concentrate at Bucquoy and were placed under orders of 41st Division. The Brigadier (Hampden) reconnoitred the area and decided to occupy the old German trench west of Achiet-le-Petit and Logeast Wood. The 8th West Yorks were on the right. Orders were issued for 25th, 40th and 41st Divisions to withdraw through the line held by 185 Brigade which later that day came back under orders of 62nd Division.

From the brigade war diary we learn that, at 3am on 26 March orders were issued for 185 Brigade to withdraw to Bucquoy

“...and take up defensive positions east of the village. By daybreak formations of Germans were seen advancing. During the morning and afternoon the enemy heavily shelled our front line and the village of Bucquoy. At about 5.30pm an attack was launched by the enemy with the object of capturing our trenches and the village of Bucquoy. This attack was completely repulsed by rifle and MG fire. Only two enemy entered our lines and these were taken prisoner. Lt Col AH James DSO, 8th West Yorkshire Regiment was killed during the day whilst engaging the enemy.”

On 26 March 1918 the battalion war diary – with no superfluous detail recorded “the commanding officer Lt Col AH James DSO was unfortunately shot early in the day.”

It seems that on the day Archie was killed, the 2/8th Battalion lost a number of other ranks killed – 16 are recorded by the CWGC for this day.

A letter from Major W H Brooke (one of the officers who had arrived from the 1/8th Battalion) was received by Sir Evan sympathising for the loss of his son (Archie was of course Sir Evan’s nephew) in which Major Brooke says how Archie was “quite fearless, absolutely without thought of himself when it was necessary to be out with the men, and he died most gallantly in the front line stopping a heavy enemy attack.”

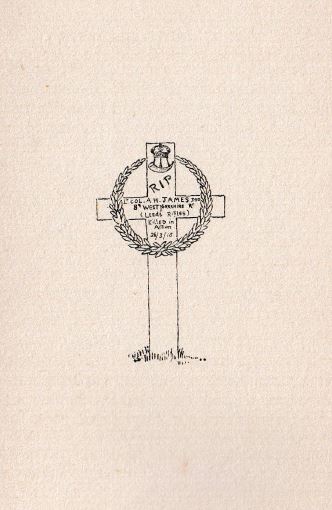

A further letter dated 9 April tells him how his nephew (he got it correct this time) was buried in the British Military Cemetery and Bienvillers-au-Bois “and I and a few men were able to attend and four buglers sounded the ‘Last Post’”.

There is an account left by ‘Bugler Laycock’ of the burial:

“He was only a young chap. He was like a father to the Battalion and was very concerned for us. I blew the Last Post for his funeral – I’m afraid the tears were streaming down my cheeks as I played. We were all very upset.”[xiv]

A third letter was sent to Archie’s brother (Commander Thomas N James, RN on HMS Temeraire) with a sketch of the cross that had been put over Archie’s grave.

This third letter adds a limited amount of detail about the circumstances of Archie’s death “… he was in our front line, a very unhealthy post, and a large body of the enemy were seen approaching. He picked up a rifle to assist the volume of fire – he was, as you well know a good shot – and a sniper got him in the head. Personally, I put it down largely to his example that a certain village is still in our hands.” (Brooke no doubt is referring to Bucquoy).

In his service file, we learn that the Gross value of Archie’s estate amounted to £22,238 (which is over £1m today).

Charles Kenneth James – March 1917 to May 1918: 2/7th West Yorks

We now need to turn the clock back a year to March 1917 and look at what it is possible to piece together about Charles Kenneth James (‘the VII’).

As previously detailed, on 11 March 1917 Charles James arrived to take command of 2/7th West Yorkshires. Charles was just 25 years old. By the end of the month, the battalion war diary records that “Major CK James assumes rank of Lt Colonel.”

There are relatively few mentions of Charles in the coming months in the battalion war diary. In one of the few references to him, we read that on 28 April “The CO (ie Charles) delivered a lecture to officers and NCOs on ‘The attack’.”

Bullecourt

For Charles with the 2/7th Battalion the April engagements damaged the unit quite badly. Based on a belief at Division that the Bullecourt salient was lightly held and the Germans were ready to make another withdrawal, patrols might have found an easy way in to the village. However, the battalion's first foray cost them one wounded officer, 19 dead and 72 wounded and 19 missing. The missing number may reflect the story that the patrols were actually in the enemy wire when the rest of the attack was postponed.

In May Charles’s men would form the support battalion to the 2/5th and 2/6th who were tasked with taking the village. Unlike Archie, Charles was operating with his own brigade but his HQ was co-located with the other Battalions in Ecoust some 1,200 yards behind the lines and the communication and control problems ensued. With the 2/6th essentially missing, 'A' Company 2/7th was sent forward in support, putting a single company into an area that had just destroyed an entire battalion. Heavy casualties occurred and no further companies were sent forward as it became clear that the survivors of the attacking battalions were now back on the start line.

It appears (from his service file) that Charles was wounded after the Battle of Bullecourt on 8 May, but presumably he was not badly injured as he remained on duty. At the very end of the month Charles went on leave (Captain Rodwell Jones MC took over in his absence) and on Saturday 2 June Charles married Phyllis Dorothy (granddaughter of Lord Westbury) at East Malling Church where Phyllis's father was the vicar. The newly married couple were only together for two weeks, as on 13 June Charles rejoined the 2/7th West Yorks.

Back in France with his battalion, we learn from the Brigade War Diary that on 19 August 1917 “…a reconnaissance carried out by Lt Col CK James DSO 2/7th West Yorks revealed a good dug out NE of Bullecourt. A large minnenwerfer was also found.”

Although we don’t know when he departed for home, we know that on 17 October Charles returned to the battalion from leave.

Cambrai

As detailed above, the 62nd (West Riding) Division was heavily involved at Cambrai at the end of November 1917 where Charles distinguished himself at Bourlon Wood.

Back in the line on the night of 21/22 November Charles with his battalion occupied Anneux and its chapel, securing the Brigade’s right flank and preventing further expeditions out of Bourlon Wood by the remains of German units probing for a gap in the line until relieved by 40th Division in the early hours of the 23 November.

For his actions, Charles was awarded a bar to his DSO. The citation for Charles’s second DSO reads as follows:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty when in command of his battalion in support of an attacking Brigade. The prominent part played by the battalion in the days’ operations was mainly due to his leadership and the information which he obtained by personal reconnaissance.”

Charles received a permanent regular commission at the rank of Captain on 22 December 1917 and the battalion war diary notes on New Year’s Day in 1918 “Captain (A/Lt Col) CK James to be Brevet Major.”

Not everything was perfect; on 10 January we see that the battalion had the embarrassment of having to hold a Field General Court Martial for one of the Riflemen, reporting on 10 January 1918 “FGCM of 267204 Rfm Harry Lobley for desertion.”[xv]

On 20 January 1918 the war diary indicates another officer temporarily took charge of the battalion, which must have been due to Charles obtaining a fortnight’s leave as we see that he returned from this leave on 5 February. Obviously this was valuable time to be spent with his heavily pregnant wife. But tragedy was to strike when his son Kenneth died two days after his birth on 17 February 1918. No doubt as a direct consequence of this Charles was able to obtain leave again on 22 February to be with his wife.

Although not something that would have concerned Charles at this time, over in 187 Brigade things were taking place that would have a direct bearing on Charles a few weeks later. This brigade (now comprising 2/4th and 2/5th KOYLI and 2/4th Y&L)[xvi] was commanded by Brigadier General Reginald O’Bryan Taylor.

Taylor went sick on 8 February 1918, leading to Lt Col BJ Barton (of the 2/5th KOYLI) being temporarily put in charge.[xvii] This temporary promotion of Barton was to have repercussions.

Back with 185 Brigade, the 2/7th battalion West Yorks marched to Bucquoy on 25 March and within 24 hours were involved in stemming the German advance towards the village. As we know Archie James (of the 8th West Yorks) was killed on 26 March during the defence of Bucquoy.

Charles’s battalion – the 2/7th was also involved in the defence of Bucquoy losing slightly more than that the 2/8th battalion – a total of 35 other ranks from the 2/7th battalion being recorded by the CWGC as being killed on 27 and 28 March.

In the days immediately after this action, the situation for the 185 brigade – and indeed the 62nd Division – was fluid.

Charles VII and his brigade command

Charles was probably devastated to hear that Archie had been killed. But the battle raged still, and matters had deteriorated over in 187 Brigade.

Here, the three battalions were being hard-pressed in the Rossignol Wood area. The brigade was being temporarily commanded by Lt Col Barton (hitherto CO of the 2/5th KOYLI) but confusion over orders from the 62nd Division led to 187 Brigade losing Rossignol Wood. The Divisional Commander, Maj-General Braithwaite, was said to have realised that Barton was ‘sick and not up to the strain’,[xviii] but his options to replace Barton were limited.

The 'replacement' commanding officer of the 2/5th KOYLI Lt-Colonel Oliver Cyril Spencer Watson DSO had been killed at Rossignol Wood on 28 March (he earned a posthumous VC for his heroics here).

Another officer option could have been to appoint Lt-Colonel Frederick St John Blacker (CO 2/4th Y&L) but he been wounded, so obviously was out of the running to take command of 187 brigade.

The third battalion commander in 187 Brigade was Lt Col Bertram Harris Hill Perry MC (aged 33), commanding the 2/4th KOYLI, but he was seriously out of favour; so much so that he was relieved of command and sent back to the transport lines by Braithwaite.

This left a major problem. To solve it, Braithwaite put the ‘sick and not up to the strain’ Barton back to battalion command (he took Perry’s battalion, the 2/4th KOYLI) and brought Lt-Colonel Charles James from his battalion in 185 Brigade to take command of 187 Brigade until a permanent replacement was found.

So, aged only 26, and after being - like Archie – a pre-war civilian, Charles now found himself temporarily in charge of a brigade.

The 2/7th West Yorks war diary details this event on 29 March with “Lt Col CK James DSO appointed to command 187 infantry brigade. Major N[orman] A[yrton] England 2/7th West Riding (DOW) Regt took over command of the battalion.”

Charles’s stint at Brigade commander of 187 Brigade was short: on 5 April he was back with his battalion as a permanent replacement, the experienced Anthony Julian Reddie was appointed to command 187 Brigade.[xix]

Upon Charles returning to the 2/7th West Yorks, Major Norman England left the battalion and was sent to command 8th West Yorks as a permanent replacement to the now deceased Archie James.[xx] The war diary also notes that the 2/7th battalion received a draft of 200 mostly aged 18 years and 9 months.

The war diary for the 2/7th West Yorks for the middle of May 1918 shows the mundane and the tragic:

11 May: brigade field day

12 May: Brigade Parade – address by deputy chaplain general Bishop Gwynne.

13 May: battalion training and bttn awarded 12 MMs for the operations on 25 March 1918

15 May: brigade holiday – held bttn sports in the morning.

17 May: bttn relieved 13 Royal Fus (37th Division)

18 May: Bucquoy. All quiet causalities: nil

19 May: bttn in line. All quiet. Lt Col CK James DSO killed by machine gun fire whilst visiting posts.

Killed – Lt Colonel CK James and 1 other rank

Wounded - Lt Powell and 2 other ranks

Charles’s wife, Phyllis, must have been devastated. Less than a year after her wedding, she had lost her new born son and now her husband. It seems from correspondence in the service file that Phyllis was living at East Malling Vicarage, Kent where her father was the Vicar of the parish church.

According to the brigade a memorial service was held for Lt Col Charles James "and others who had fallen" on 2 June. Divisional and Brigade staffs attended. After Charles’s death there was no immediate appointment of an officer to command the battalion. This was unusual and his death probably made it easier for GHQ to make the next decision.

2/7th West Yorks disbanded

Reinforcements were needed on the western front. Whilst many young soldiers had been sent over from the UK, there was a significant number of troops out in Palestine. It was decided to send various battalions from there to the western front. One of these was the 1/5th Battalion of the Devon Regiment, serving with the 75th Division. This battalion was sent to the 62nd (West Riding) Division and to ‘make room’ for it an existing battalion would have to make way.

On 15 June, it was stated in the 185 Brigade’s war diary. “The 2/7th West Yorkshire regiment ordered to be disbanded and the 1/5th Devon Regiment (which had been part of the 75th Division, operating in Palestine) to take their place.”

The next day,16 June, it was noted in the 2/7th West Yorkshire Regiment’s war diary “battalion disbanded”. There was, of course, a lot of men to be moved to other battalions.

In the war diary it notes that 3 officers and 131 OR went to the 8th West Yorks – so they remained ‘Leeds Riflemen’. A further 4 officers and 160 other ranks went to join the ‘other’ West Yorkshire battalion in the 62nd Division (the 2/5th West Yorks). Others, however, were less fortunate: 15 officers and 426 other ranks were sent to the base and they presumably went to assorted other units. A small number of others (10 officers and 47 other ranks) had - a few days previously - been sent to form a training staff for American units in the UK.[xxi]

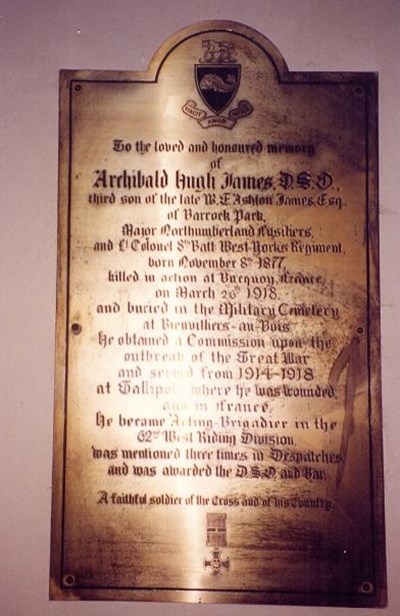

After the war: resting places and commemorations

Five years after Charles’s death, his widow Phyllis married William Cursham. She lived until 1976. Lt Colonel Charles Kenneth James is named on the Ightham War Memorial where Charles and Phyllis were probably planning to live.

Charles is also named on a plaque in East Malling Church where he was married less than a year prior to his death.

Charles is buried at Bienvillers Military Cemetery, which is just five miles northwest of Bucquoy.

The personal inscription on his headstone, no doubt requested by Phyllis is “Rejoice and be exceeding glad for great is your reward in Heaven”. In the grave next to Charles is the soldier who was killed with him on 19 May, Rifleman Ralph Metcalf.

Also buried also at Bienvillers - in the final coincidence that links the two commanding officers Archie and Charles - is Archibald Hugh James. His headstone’s personal inscription simply records “Commanding the 8th West Yorkshire Regiment”.

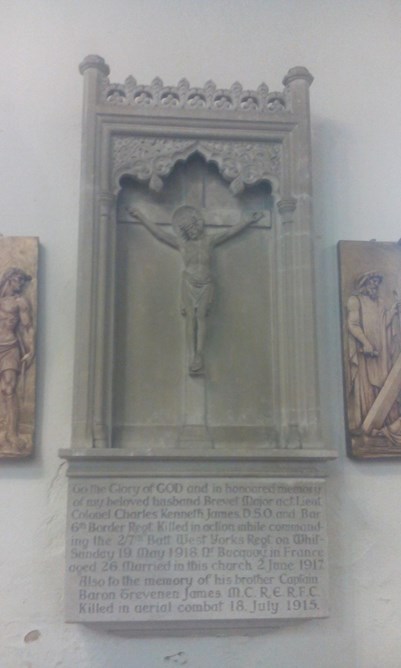

Archie is also commemorated on a church memorial in High Hesket, very close to the family home, which stayed in the family for many years.

Conclusion

As stated in the footnote in the Division’s history, the loss of Archie James was a grievous blow. Although we can’t be certain, it is a distinct possibility he would have been promoted to Brigadier General before the war’s end. Archie’s death was then followed relatively soon afterwards by that of the very young (26 years old) Charles James. For Charles to be promoted to command an infantry battalion, just weeks after his 25th birthday is remarkable.

Despite these losses, the war carried on, and the next time Brigadier General Hampden was on leave on 3 August, Lt Col Waddy of the 2/5th West Yorkshires took temporary charge of the 185 Brigade.

The youth of Charles James in being – even for only 3 days – an acting Brigadier General could of course be compared to that of Roland Bradford who was gazette as a Temporary Brigadier General in 186 Brigade on 13 November. However such comparison between Charles and Roland Bradford does not really stand scrutiny. The promotion of Roland Bradford is entirely different to 'filling in' for three days, but the fact that both Charles and Archie were civilians on the outbreak of war (albeit with some military service in ‘exotic’ units in the Empire) could well be argued make their promotions even more spectacular than the pre-war regular Roland Bradford (a pre-war territorial from 1910, Bradford became a ‘regular’ in 1912) who of course is famously the youngest soldier to hold the rank of Brigadier General.

Other young officers also took command of Brigades. Peter Hodgkinson has helpfully highlighted a number of officers who were promoted from Lieutenant Colonel to Brigadier General and from this we can see a small number of officers, besides Roland Bradford, who were very young when promoted to this rank.

In May 1918, Archibald Bentley Beauman took command of the 69th Brigade of the 23rd Division, He was 29 years old.

On 1 October 1918 Charles William Frizzell took command of 75 Brigade (25th Division) he was aged 30

Asked about the ages of battalion commanders John Bourne provided a list of those who were in command of battalion as at 29 September 1918. Although this date is four months after Charles died, and more than eighteen months after the Charles first gained command of his battalion, the data shows that his promotion at such a young age, although not unique, is certainly rare. Only fifteen men who were commanding battalions on this day in September 1918 were aged 25 or below.[xxii] Of these 15 men, just five are known to have been pre-war civilians. Clearly Charles was one of a very small number of officers to be battalion commanders at the age of 25 years.[xxiii]

Archie’s promotion to acting/temporary Brigadier General despite not being in the Army on the outbreak of the war must be highly unusual, if not unique. Others made it to the rank (albeit it ‘Temporary’) of course, but very few of these seem to be anything other than pre war regulars.

How many officers acted up as temporary Brigadier Generals? Without inspecting every brigade war diary for the entire period of the war, it is impossible to say, but this was probably quite a frequent occurrence with leave, courses and other absences needing to be filled. But the question applies: How many of these officers who acted as temporary Brigadiers would have been pre-war civilians?

So whilst not claiming either Archie or Charles as being unique in their service, I would suggest that they are very unusual to have risen to so far and so fast. It is even more unusual that not only were both men in the same Division, they served in the same infantry brigade, and were both commanding battalions of the Leeds Rifles.

The memorial to all men who were killed in the Leeds Rifles can be seen on the pavement outside Leeds Minster.

In memory of:

Charles James, DSO* Border Regiment, CO of the 2/7th West Yorkshire Regiment (Leeds Rifles), and

Archibald James, DSO* Northumberland Fusiliers, CO of the 8th West Yorkshire Regiment (Leeds Rifles).

Acknowledgments

Prof John Bourne

Rory Constant

Dr Peter Hodgkinson

Fraser Skirrow

A note on 'Acting/Temporary' Brigadier Generals

At various points in this article I have referred to temporary and acting officers, particularly those who acted as Brigadier-General. It is necessary to make a distinction between those who were acting in this role for an extended period, and those who (like Archie and Charles) were temporarily 'filling in' for a short period whilst their senior officer was either on leave, on a course, or 'acting up' himself as Divisional Commander.

Dr Peter Hodgkinson pointed out early in the research "It is important to consider the use of the word "acting". It is clear that [Charles] James was acting in place of Barton, but he was not an "Acting Brigadier General". Similarly, Baptist John Barton is described as "acting" (from 8 February) [but] is never an "Acting Brigadier-General". Generally officers had to have held a role for 28 days before they were officially dubbed as "Acting".

Prof John Bourne stated: It needs to be remembered that Brigadier-General is not a rank but an appointment. I don't think that 'Acting' was a formal position.

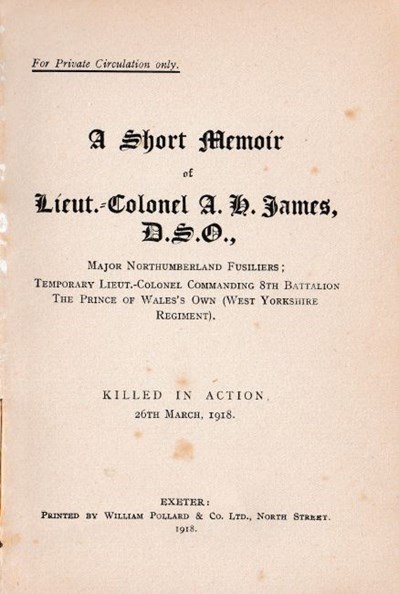

A note on sources

Archie's 'Uncle Evan' (Sir Evan James) created a memorial book detailing his nephew’s life. 'A short memoir of Lieut.-Colonel A.H. James, D.S.O.' A copy of this is probably with the Imperial War Museum (Catalogue number LBY 3807) but it proved impossible to get hold of this. Fortunately, with the assistance of Fraser Skirrow (who kindly summarised aspects of the battalion actions at Bullecourt and Cambrai) I was able to make contact with Archie's descendant, Rory Constant who had a copy of this memorial book which he was willing to share with me.

It is likely that this book will provide material for a future article about Archie's war service in Gallipoli. Rory was also able to add some family background to Archie's story. I am very grateful to Rory for his assistance.

Unfortunately, in comparison to the rich availability of material on Archie, there is very little available about Charles James. Much of the biographical information on Charles was gleaned from his entry in the 'de Ruvigny Roll of Honour' volume 4, which is available online at Ancestry.

Some additional information was available in the two service files which are at The National Archives:

Service File for Archibald Hugh James: WO 339/10013

Service File for Charles Kenneth James: WO 339/24351

War diaries were extensively inspected, with the 185 Brigade War Diary (WO 95/3079 and WO 95/3080) providing some nuggets of information. The battalion war diaries for 2/7th West Yorks (WO 95/3082) and the 2/8th (and 8th) West Yorks (WO 95/3082 and 95/3083) were also extensively consulted to glean mentions of Charles and Archie.

In addition, use was made of the war diaries of the 6th Battalion Border Regiment (WO 95/1817) and 8th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers (WO 95/1821) both in Gallipoli and France.

References:

[i] Baron James' involvement with the Great War was brief but it was highly productive. On the 13th July 1915 he was killed by a shell fired at his aircraft whilst he flew a solo test mission over the enemy lines. He was evaluating wireless equipment that had been largely developed by himself and Captain Donald Swain Lewis, RFC. One of his enduring achievements was the development of the 'clock code' that established the relative positions of targets for the artillery. The practice became widely used during the War for other applications, and is still widely used. The fate of James' colleague and close collaborator, Donald Lewis, was even, if possible, more ill-fated: Lewis was shot down on the 10th April 1916 by the very guns of the battery with which he had been co-operating. (Cited from: http://www.militarian.com/threads/captain-baron-trevenen-james-1889-1915-rfc.4015/)

[ii] Ray Westlake 'British Regiments at Gallipoli' (Pen & Sword)

[iii] This was more commonly termed ‘Trench Fever’.

[iv] The Times, 15 November 1916

[v] Some second line territorials had arrived on the western front during 1916, such as the 61st (South Midland) Division which had arrived in France in May 1916, and the 60th (London) Division in June 1916. A few other territorial divisions arrived subsequently later in 1917: 57th 58th and 59th in February 1917 and the 66th in March 1917.

[vi] Besides being a well known cricketer, another claim to fame is that Jackson’s fag at Harrow school was none other than Winston Churchill !

[vii] Jackson purportedly went home as he was a newly elected MP – but this may not have been the real reason for him being sent home

[viii] Lawson died in 1982 aged 98 – the last of the individuals detailed in this account to have been alive

[ix] Everard Wyrall, The West Yorkshire Regiment in the War 1914-1918, volume 2 (John Lane The Bodley Head Ltd), p.142

[x] Hoare was wounded at Cambrai on 22 November 1917

[xi] Brig-Gen Thomas Walter Brand, Viscount Hampden VB CMG took over command of 185 Infantry Brigade vice Brigadier General VW de Falbe CMG DSO who proceeded to England (owing to ill health).

[xii] Brig General Roland Bradford was killed little over two weeks later and so the commander of 186 Brigade was temporarily handed to Lt Colonel HEP Nash until the appointment of a permanent replacement being Brig-General JLG Burnett on 3 December 1917. (Burnett was promoted from command of 1st Battalion, the Gordon Highlanders).

[xiii] Katharine Mary (née Montagu-Douglas-Scott), Viscountess Hampden a daughter of the 6th Duke of Buccleuch

[xiv] Andrew Kirk, Leeds Rifles (Pen & Sword), p262

[xv] Lobley may or may not have been found guilty, but he survived the war, and seems to have later been transferred to the Royal Fusiliers.

[xvi] The other battalion of the brigade, the 2/5th Y&L had been disbanded in the reorganization

[xvii] Barton had taken command of the 2/5th KOYLI in May 1917 when the previous CO had been killed.

[xviii] Malcolm K Johnson, Saturday Soldiers, The Territorial Battalions of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (Doncaster Museum Service), pp 137-138

[xix] Reddie (1873-1960) was 45 years old and a pre-war regular.

[xx] England took over Archie's command despite Longbottom (the former CO of the 1/8th Battalion (49th (West Riding) Division being a member of the 8th Battalion. The conclusion from this is that Norman England was considered a better commanding officer than Longbottom. England commanded the battalion until the Armistice.

[xxi] This suggests that just before being disbanded, the battalion strength had been 32 officers and 764 other ranks (however this includes the 200 OR that had joined in April, clearly the battalion had, prior to this, been under strength).

[xxii] Admittedly there may have been some older men, who had been in command for a while

[xxiii] The youngest battalion commander as far as can be seen (as at 30 September 1918) was Douglas Marks. Born on 20 March 1895 he was promoted to acting Commanding Officer on his 22nd birthday (20 March 1917) but was wounded within days. He was then given the temporary rank on his recovery and commanded the 13th battalion, AIF from December 1917 to the end of the war.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.