Life and Death on the North Sea during the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Life and Death on the North Sea during the First World War

Perhaps the subtitle of this piece should be 'Just One Week', for that was the length of time one of my paternal uncles had served aboard HMS Queen Mary before she sailed out into the North Sea to meet the German Fleet. Although most of my other family members served in the Army during the Great War, the twist of fate that caused James Ringland to lose his life has always resonated deeply.

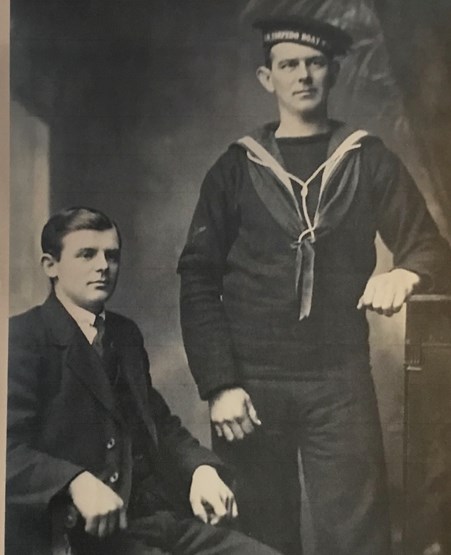

Above: David (left) and James Ringland taken in April 1916

James was born in Kilwinning, Ayrshire in 1886. His parents Robert and Helen had a family of nine, but were to lose another son in the Great War. In common with thousands of households, the years 1914-1918 brought great sadness to my grandmother. On 14 October 1915 her 21 year old son John, known as Jack, was killed in action in Gun Trench in the Loos sector serving with The Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment. Finally, Helen’s husband died in 1918, but at least she had the comfort of close family support at her home in West Kilbride.

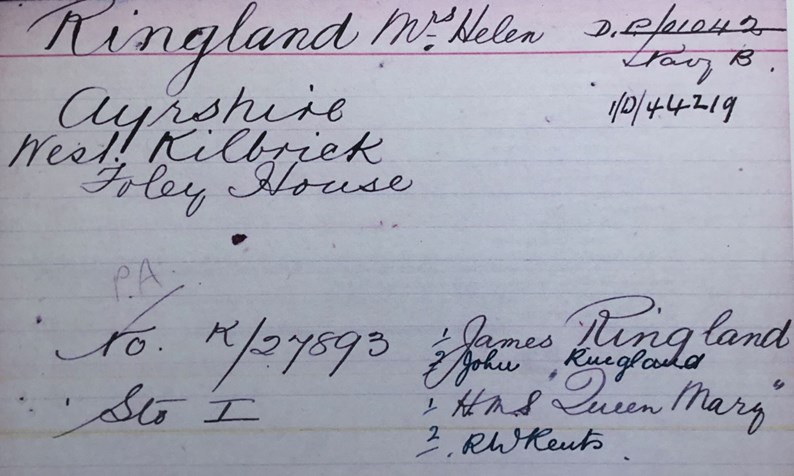

Above: Dependant’s Pension card for Jack Ringland indicating it had been passed to the Navy Board for James to be added

Above: Pension index card for both sons.

Before the war James had worked on the Glasgow & South Western Railway as a fireman on steam locomotives. Two of his brothers were in the Merchant Navy, and so on 25 August 1915 James enlisted in the Royal Navy, utilizing his civilian job to become a Stoker First class K27893.

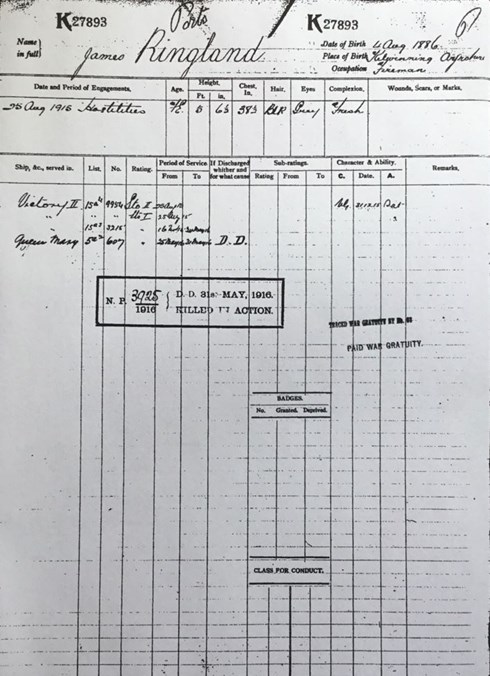

Above: Page from the Stokers’ Ledger with James’ details.

Once a man had completed initial training, parade drill, rifle drill and naval history, they were assigned to HMS Victory II, as shown on James’ record. This was a land based training establishment for stokers and engine artificers based in Portsmouth. In 1915, Victory was transferred to Crystal Palace in south London, then relocated to Portsmouth at the end of the war. Men had to study the “Stokers’ Manual” which set out the basics of boilers, furnaces, engines, turbines and the registering of temperature, steam, oil and water gauges.

Large battleships could take up to five hundred tons of coal to bring them to steaming heat. It was essential to stoke the furnace evenly to ensure no cool areas, so gauges had to be regularly checked. To progress up the ranks, a 600 page manual had also to be learned, but with his railway experience James became a Stoker First Class immediately. Stokers received better pay than the ordinary seaman as their work was more arduous. They worked a four hour on, eight hours off shift pattern, often enduring forty degrees Celsius in the furnace areas. They had their own Mess and washroom areas onboard and generally took turns with chores, including cooking when coming off a late watch.

The final entry in James’ record shows that he was posted to HMS Queen Mary, when she was in her home port of Rosyth. The date is 25 May 1916, just one week before the ship took part in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916.

Above: HMS Queen Mary leaving the River Tyne for sea trials in 1913

Jutland brought together the two strongest naval powers of the time -the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet. The battle cruiser HMS Queen Mary had been built at Jarrow-on-Tyne and launched in 1912. She was propelled by four geared steam turbine engines, with a speed of 27 knots. Her armaments consisted of eight 13.5” guns in four twin turrets with a range of 13.4 miles, sixteen single mounted 4” guns with a range of 6.5 miles, plus two torpedo tubes with a range of 6 miles. When she sailed from Rosyth in May 1916 to engage the German Fleet her crew numbered 1,264, out of which only 21 survived.

James was amongst the casualties, and is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial situated on Southsea Common. Additionally, he is named along with his brother Jack on a memorial window in St. Andrew’s Church, on the village War Memorial, and on his parents’ headstone, all in West Kilbride, Ayrshire.

Above: The last moments of HMS Queen Mary at Jutland.

The Record of the Battle of Jutland was prepared for the Admiralty by Capt. J.E.P. Harper, MVO, R.N. in 1919 to 1920. It details every move of the Grand Fleet over the two days of battle, and gives the following entry relating to HMS Queen Mary.

“At 4.26pm. a plunging salvo pitched abreast Q turret of Queen Mary (this was apparently the first time Queen Mary was hit), and almost instantaneously there was a terrific upheaval and a dense cloud of smoke. This could not altogether be avoided by Tiger as she was 2 cables from Queen Mary.

As Tiger passed through the cloud, about 30 seconds after the explosion, there was a heavy fall of material on her decks, but no sign could be seen whatever of Queen Mary. She sank instantaneously in Lat. 56⁰ 42’ N., Long. 5⁰ 49¼’ E. Seventeen survivors were subsequently picked up by Laurel and one by Petard.

Tiger now shifted fire to the third ship from the left, and established hitting. The enemy destroyers which had moved out, were observed to turn to attack. Tiger opened fire on them with her 6-in. guns and appeared to find their range after three salvoes, range 11,000 yards.”

One of the survivors picked up By HMS Laurel was Midshipman J.L. Storey, who was the senior uninjured survivor, and he wrote an account of his experience which was sent to Rear Admiral Osmond Brock.He was commander of the First Battlecruiser Squadron with his flag in HMS Princess Royal. During that battle Brock played an important role repeating messages from Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty Commander of the Battlecruiser Fleet, whose radio was out of action. When Beatty was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet in November 1916, he took Brock with him as his chief of staff.

Storey stated,

“Sir, I deeply regret to report that HMS Queen Mary, commanded by Captain C.I. Prowse, R.N. was completely destroyed when in action with the German Fleet at 4.25 pm. on Wednesday, the 31 May."

The circumstances of the loss of the ship are, as far as I know, as follows. At 3.20pm. the Queen Mary was third ship in the line of the First Battlecruiser Squadron and action was sounded, and at 3.45 the order was given “load all guns”. At 3.53 fire was opened on the third ship of the enemy’s line, the range being about 17,000 yards.

The fire was maintained with great rapidity till 4.20, and during this time we were only slightly damaged by the enemy’s fire. At 4.20 a big shell hit Q turret and put the right gun out of action, but the left gun continued firing. At 4.24 a terrific explosion took place which smashed up Q turret and started a big fire in the working chamber and the gun house was filled with smoke and gas. The officer on the turret, Lt. Cmdr. Street gave the order to evacuate. All the unwounded in the gun house got clear, and as they did so, another terrific explosion took place and all were thrown into the water. On coming to the surface nothing was visible but wreckage, but around thirty persons appeared to be floating in the water.

At 4.55 HMS Laurel saw the survivors in the water and lowered a whaler and rescued seventeen. When this number had been picked up Laurel received order to proceed at full speed, being in grave danger of the enemy’s ships. All were treated with the greatest kindness by the men of Laurel, and were landed at Rosyth at about 8pm on 1 June.”

Another ship, HMS Lydiard, also received a message ordering her to pick up survivors. However, there was difficulty with the heavy wash caused by the Fifth Battle Squadron passing and re-passing at close range which made this impossible. HMS Petard reported picking up a survivor, but with the enemy closing, was ordered to rejoin the main flotilla.

As third ship in the British line, HMS Queen Mary had SMS Seydlitz as a direct opponent, but changed target to SMS Derfflinger, which had been firing on HMS Lion, David Beatty’s flagship. In the smoke of battle Derfflinger lost sight of Lion and so changed target to Queen Mary.

Korvettenkapitä Hase, I Artillerie Offizier of Derfflinger recorded in his diary,

“So the Queen Mary and the Derfflinger fought out a regular gunnery duel over the destroyer action that was raging between us. But the poor Queen Mary was having a bad time. In addition to the Derfflinger she was being engaged by the Seydlitz, and the gunnery officer of the Seydlitz, Korvettenkapitän Föerster, was our crack gunnery expert, cool headed and of quick decision.”

Meanwhile on Seydlitz, Föerster noted,

“Suddenly on our opponent I saw a flash in the aft ship that grew visibly, and this offered to the eye a scene that could move one deeply, but this could not be thought of. In a giant smoke cloud the ship seemed to lift itself from the water, shattered in the middle, with debris flying all around.. The whole picture framed in a blue-red fire glow. The report that their opponent had blown up was passed around the ship. “Drauf Seydlitz” (On it Seydlitz!) was the reply from the crew, as they prepared to engage their next target.”

Under heavy shelling from Seydlitz and Derfflinger, one of the front magazines exploded, and the detonation carried on into the midship, it is thought because not all flameproof bulkheads between the compartments were closed. In order to shorten reloading times, gun turret crews often positioned large amounts of cordite propellant in the gangways, thus blocking the bulkheads.

After Jutland Germany made the most of its lighter losses of men and ships, while in Britain the Navy was criticised by many for its apparent failures. It was reported that a Daily Mail journalist in search of news was interviewed at the Admiralty by Captain Reginald Hall, Director of Intelligence Division (DID), who told him he was making a fool of himself, as the Navy had done very well. ‘ “How do you make that out?” said the reporter. “‘Well”’ said the DID, “if I kick you out of this room, which I shall do presently, and you can’t get back again, isn’t that a victory for me even if I get a black eye in the process.” ’ (National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/357, pp.8-9). It was also reported that workers on the Forth Bridge threw stones and lumps of coal at the ships sailing back to their base at Rosyth, calling them cowards for “running away” from the German fleet.

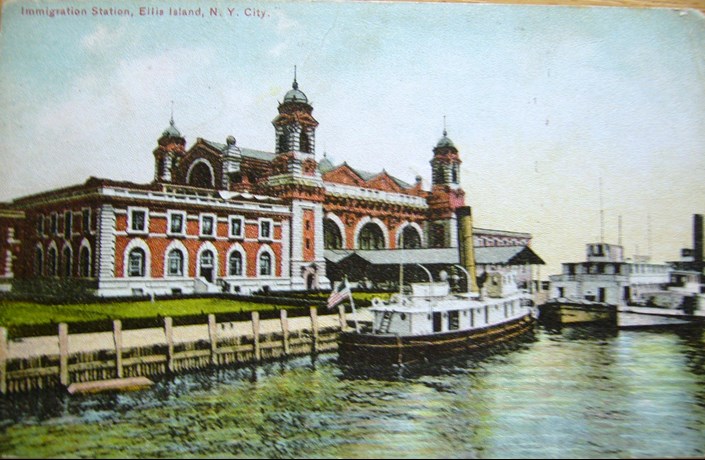

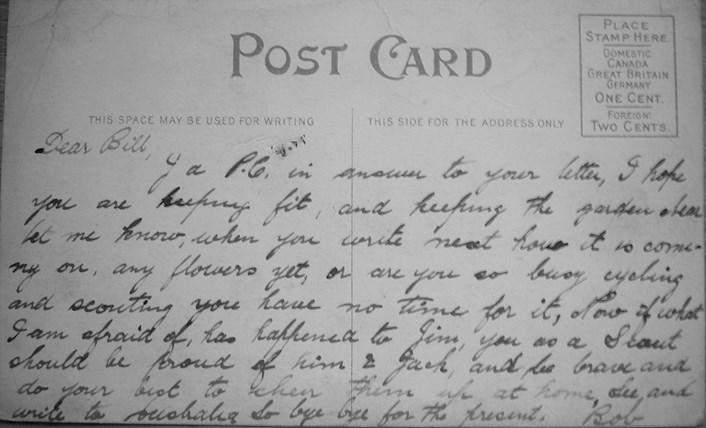

As news gradually filtered back to this country about Jutland, there was clearly uncertainty within the Ringland family about James’ outcome. His elder brother Bob was in New York on a merchant ship, and sent a postcard home which gives a clue to what the uncertain situation.

Above: postcard sent by Bob Ringland from New York, addressed to younger brother Bill.

Bob wrote,” Now if what I am afraid of has happened to Jim (James), you as a Scout should be proud of him and Jack. Be brave and cheer them up at home. See and write to Australia (his destination on that voyage).So bye bye for the present. Bob.”

As an aside to this narrative, my uncle Bob Ringland served in the Merchant Navy all his life, and had the dubious distinction of being onboard ships torpedoed in both world wars, and living to tell the tale. Research is ongoing for that subject.

On the 100th anniversary of Jutland, a national service of Commemoration was held in Orkney in St. Magnus Cathedral. Outside the church The Weeping Window, a superb part of the Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red poppy installation from the Tower of London was displayed, and Orkney organised some impressive events.

On 31 May 2016 I had breakfast in Kirkwall Town Hall, ahead of the formal church service. Relatives of those who fought attended, and we wore badges with our name and the ship we were associated with. So it was a case of peering at peoples’ shoulders in order to find others with a Queen Mary interest. I could never have imagined that exactly one hundred years after the battle, I would be discussing the event with Lady Diana Beatty, Admiral Sir David Beatty’s granddaughter. She had rather hidden herself in a corner of the vast hall, but I spotted the surname , so there was no escape. Apparently, some of her relatives advised keeping a low profile in case the Jutland descendants still bore a grudge against the Admiral !

After the end of the official programme, it was tea and cakes time back at the Town Hall, and another chance to resume conversations.

Above: Dora Ringland foreground with Peregrine Dearden’s granddaughters

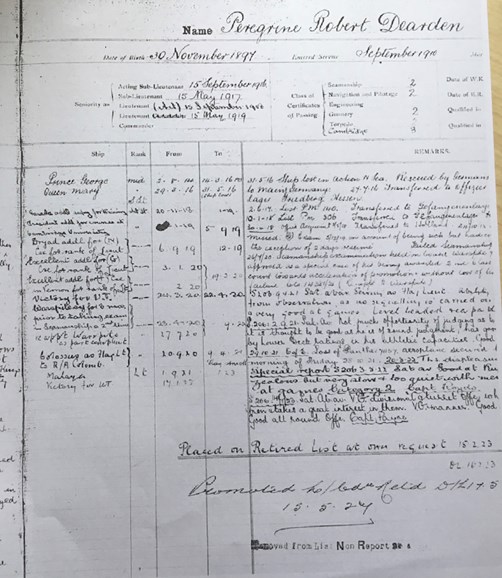

It was at this point I met relatives of one of Queen Mary’s survivors, Midshipman Peregrine Robert Dearden. Born in November 1897 in New Zealand, he came to England for his education and enrolled at the Royal Naval College Osborne in September 1910. Peregrine’s Naval Record sheet survives, and his first posting was to the battleship Prince George in August 1914 where he remained until 14 March 1916.

Above: Peregrine Dearden’s Naval Record sheet

Unlike James Ringland who had only served one week on Queen Mary before Jutland, Peregrine had been onboard for nine weeks before 31 May 1916. The remarks column of his record only tersely states - Ship lost in action N. Sea. However, this did not mean death in his case, but life, as he was rescued by the German torpedo boat V28. On the 27 July 1916 Peregrine was taken to the first of three prisoner of war camps he was held in. He was initially reported as killed in action in the national press, so it must have come as a huge relief to his family when a letter arrived from him. One of his relatives, Juliet Dearden, kindly sent me copies of his letters home, and his first letter to home follows.

Above: Peregrine as a prisoner of war

Kriegsgefangensendung – Midshipman P. R. Dearden, Abteilung 3, Stube 31, Offizier Gefangenenlager Friedburg, Hessen.

"June 5 1916

Dearest Mother,

We arrived in this camp the day before yesterday and are looking very ragged at present, having no money or clean clothes. We, being myself and six officers from two destroyers. We left harbour as usual not expecting anything special to happen. About 3.45pm on the 31 we went to action stations and had everything ready, and we opened fire and after about an hour and a half of engagement there was a terrific explosion forward, and I was sent on the top of our turret (after turret) to see what was happening and had to put on lung respirators owing to clouds of smoke and fire.

I could see nothing for a minute and then all cleared away as the foremost part of the ship went under water. I then told the officer of the turret that the ship was sinking rapidly, and so many as possible were got up out of the turret. The whole foc’sle was almost blown off and I immediately took off all my outer gear except my shirt and vest, everyone else going in all standing. As soon as in the water I swam clear and astern of the ship about 30 yards when she suddenly blew up completely.

I was luckily sucked under water and so all the wreckage chuck about did not come with its full weight on my head. I held my breath for a long time and at last came to the surface. I started looking around for something to support me as much as possible.

As you know I never had a Gieve waistcoat * and now I am glad I had not. The surface of the water was simply covered with oil fuel which tasted and smelt horribly. With presence of mind I smothered myself all over with it, which I really think saved my life, as the water was frightfully cold. I should say that about fifty hands went over the side, but about half these were killed during the second explosion. Most of the remainder of us held out on two or three spars and other wreckage on the surface.

Shortly afterwards, several of our destroyers came up, but only one stopped and you know as well as I do how many were saved by her. This was about half an hour after we had been in the water, and it nearly drove me frantic when she steamed off when I was only about twenty five to thirty yards away from her. She would not even leave her whaler behind to pick up the remaining men in the water, although I shouted at them to do so. Afterwards it was terrible seeing everyone collapse and drown, and I had not the strength to help any of them. I only saw two officers in the water, an RNR assistant paymaster and RNR Sub.Lt. Percy. The people with Gieve waistcoats on were the first I noticed to drown, as they were held a little too high out of the water, and when they became weak their heads fell forward in the water.

My next memory was being put to bed, and I had a good ten hours sleep, after which I got up and had breakfast feeling somewhat restored. I am at present in the citadel fortress at Mainz, and really had a most interesting journey down the Rhine. I think Aunt Mabel’s fortune telling about having a lucky hand must have been true. Will you let me know how many officers and men from the QM were saved, and also the names of the officers? I was very well treated in the German ship that picked me up, and was given an egg for breakfast. I hope Jim** is keeping well, and will continue to have good fortune.

With very best love to you all. Your loving son, Peregrine.”

*Gieve waistcoat was sold at fifty shillings by the Naval outfitters, later to become Gieves & Hawkes. It boasted itself as “world famed by its continual record of life saving. Worn as an ordinary Waistcoat under uniform, fitted with brandy flask, inflated easily in a few seconds, it forms the one known and reliable means of life-saving from U-boats and mine disasters.”

**Jim was Peregrine’s brother Captain James Ferand Dearden, DSO, MC. Royal Fusiliers who died age 23 on 6 October 1919.

From Mainz, Peregrine was moved in June 1916 to Friedburg, Hessen. A year later came a further move to Clausthal in the Harz Mountains, where officers were quartered in the Kurhaus. His final move in January 1918 was to Holzminden Camp in Lower Saxony. At this point Peregrine became ill, and on 3 May 1918 he was sent to Holland in an exchange of prisoners on medical grounds. Some five months later on 28 October 1918 he arrived in London, travelling on to rejoin his family in Cheltenham.

Peregrine remained in the Royal Navy for the next five years, achieving the rank of Lt. Commander, but by 1923 was placed on the Retired List at his own request. In that year he went back to New Zealand and followed his father’s business in farming, until he died in 1952. So here were two men, serving on the same ship, present at the same momentous naval battle, but with two very different outcomes.

After the main Orkney commemoration took place in Kirkwall, a further service was held at Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery on Hoy, where German and Royal Navy sailors are buried. Additionally, on 31 May 2016 ships from both navies met in the North Sea to cast wreaths at the site where so many lives were lost. The Jutland Memorial Park Thybøron, Denmark was also opened in 1916. Here high stone obelisks were erected to represent every ship that sank. Around these eventually, smaller stones have been placed to commemorate the total of 8,645 men lost. In the German Naval Museum, Wilhelmshaven, Vizeadmiral Andreas Krause, Commander in Chief of the German Navy was present at an exhibition to mark the centenary of Jutland. His opening remarks included a quote from von Clausewitz. “War has no victors, every military triumph proves itself in truth to be the defeat of all participants”.

Shortly after Jutland, or Skagerrak as it was known to the kaiserliche Kriegsmarine , Wilhelm II congratulated sailors of the High Seas Fleet by declaring that English global domination had been ripped down “and the tradition of Trafalgar torn to shreds”. With the hindsight of over one hundred years, however we evaluate Jutland today, it may always remain contradictory in terms of winning and losing.

The label on a poppy wreath I laid for James Ringland contained what I felt to be an appropriate quote from a book written by the author Nicholas Monsarrat. “Imagine being a stoker, working many feet below the waterline, hearing the crack of explosions, knowing exactly what they mean, and staying down there on the job, shovelling coal or turning wheels. Concentrating, making no mistakes, disregarding what you know may be only a few yards away and pointing straight at you. No amount of publicity, no colourful comments, above all no medals, can do honour to men like these.”

Remembering all those on both sides who fought and died on 31 May 1916.

Article submitted by Dora Ringland