Major Arthur Hughes-Onslow: soldier, jockey and one of the first British deaths in the Great War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Major Arthur Hughes-Onslow: soldier, jockey and one of the first British deaths in the Great War

Arthur Hughes-Onslow was born in 1862. He joined the 10th Hussars at Lucknow, India and stayed in the regiment for 20 years. Along the way, he acquired the nickname of 'Junks', although he had no idea why it was given to him.

It soon became the name by which he was known by family, friends, the racing public and fellow soldiers alike. Everyone who served in the Cavalry had to be competent in the saddle, but Hughes-Onslow seemed to have exceptional skills at a horseman. He was a longstanding member of his regiment's polo team and a renowned steeplechaser. At Sandown Park in 1888 he rode the winner, Bertha, in the Grand Military Gold Cup, the most prestigious race for gentlemen jockeys and an event he was to win on two further occasions.

He hunted regularly and widely across Ireland and in Yorkshire. He raced whenever the opportunity presented itself and, with his constant successes, was much in demand. He was rarely beaten in regimental point-to-points and, whether riding his own or his fellow officers' mounts, was first home more often than he was bettered. In 1898, he repeated his success in the Grand Military Gold Cup, bringing County Council home by 15 lengths.

The following year, he achieved a clean sweep of the big races in Ireland, with the Irish Military Steeplechase, the Irish Grand Military Steeplechase and the Conyngham Cup. In each race he was riding for his friend and fellow officer Captain Eustace Loder of the 19th Lancers. Their association was long and fruitful and the Conyngham Cup – Ireland's most prestigious steeplechase – was to be theirs on three occasions, all on the same horse, Covert Hack.

In his hunting journal – a gift from his brother Con in 1891 – Hughes-Onslow faithfully recorded his days with the hounds and on the racetrack. He would spend on average 55 days each season hunting in different parts of the country. He records the day's sport and the horses he rode. In 1893 he mentions, for the first time, Belwade at the York and Ainsty Hunt. In the years that followed, in spite of having several horses at his disposal, Belwade and – from 1895 – Tinneranna 'did most of the work'. Belwade carried him after the foxes more than any of his other hunters and Tinneranna was rarely beaten at either regimental events or at point-to-points.

The war in South Africa

In 1899, his regiment was bound for South Africa and the Boer War. A and B Troops of the 10th Royal Hussars, under the command of (by now) Major Hughes-Onslow, a battery of the Royal Artillery and a detachment of the Royal Army Medical Corps, set sail for the Cape on the SS Ismore. On board were 300 horses. While troopers were issued with good quality mounts, officers supplied their own and were required to have two available: one a charger, and one at least being 'a capable riding mount'. Hughes-Onslow took two of his best horses – Belwade and Tinneranna - old friends he had been riding for years.

It was a desperate voyage for the animals. The Ismore had to turn back at one stage because the horses suffered badly in the weather conditions. 24 horses died during the voyage, but the worst was yet to come. In the early hours of 2 December 1899, just 100 miles from Cape Town, the ship left her intended course and ran aground.

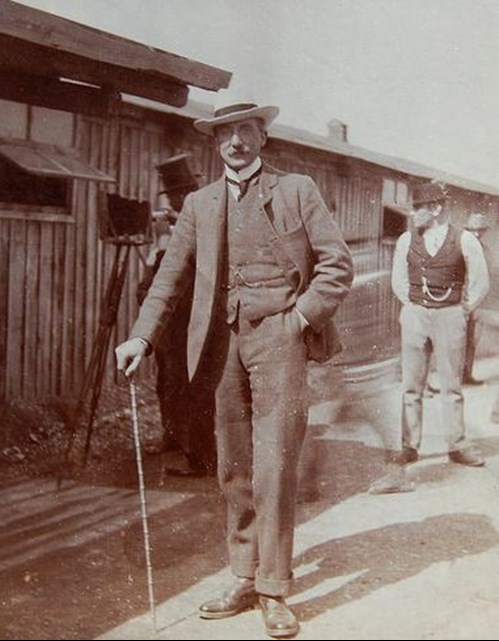

Image: Hughes-Onslow;centre on the Ismore with fellow officers

The Ismore was stuck fast on rocks about a mile off the shore; 'a fearful ironbound coast', as Hughes-Onslow described it in a letter home. The letter, to his wife Kathleen, provides one of the most vivid accounts of the shipwreck:

We could do nothing for the horses except throw them overboard, which we did to as many as we could, but only twenty five all told got ashore, and some of them are terribly injured by the cruel rocks. During the day we made several journeys to the ship and got off as much kit as we could but during the night the wind freshened, and now the ship is an utter wreck and quite unapproachable, and it is dreadful to think of the loss of our beautiful horses.

Other accounts reported that most of the animals thrown overboard swam round the ship until they drowned, or headed out to sea in their confusion. The rest were left loose on board in the hope they would manage to swim clear when the vessel broke up. Of the 300 horses that left England, only 20 made it safely onto South African soil.

Hughes-Onslow related that, remarkably, both Tinneranna and Belwade survived. The former was 'quite well' but Belwade was in a very weak state 'for he was as near drowned as it was possible to be.

The surviving horses were walked in easy stages to Cape Town while the men marched 12 miles overland to Paternoster, where they boarded a ship to continue their journey. As they left the scene of the shipwreck, dead horses were coming ashore on each tide.

The Boer War was not kind to animals. The troops and their mounts covered huge distances with little in the way of food and water to sustain them. An officer of the 11th Hussars wrote in 1900:

..... horses may be seen starting their trek with the ship's marks hardly off their quarters. Day after day these animals are called up on to carry the same heavy man and his equipment from morning until night on a few pounds of oats and any grass he can pick up along the way. Added to which he will probably be called upon one night of the week to carry out a forty mile raid in addition to the march of the previous day. No horse alive can last more than a few months under these conditions, and if he is unfit to start with, it is generally a question of weeks and sometimes days.

The life expectancy of a horse in the Boer War was under 6 weeks. As many as 300,000 horses and 150,000 mules died on the British side alone, either in battle, of disease, of exhaustion or from a straightforward lack of forage. Nor did the situation improve as the war went on, supply never catching up with demand.

In his history of the war, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle reported that, after they had advanced hard and fast to cover 100 miles in 4 days with little water and short rations, 'the horses were so done in that it was not uncommon to see a trooper walking to ease his horse while also carrying part of his monstrous weight of saddle gear.'

Then, after crossing the withered veldt, General French sent his cavalry, men and horses reported to be 'mad with thirst', on a 9 mile charge towards Kimberley, with 'nothing to shield them from the heat of the sun other than the dust kicked up by the horses' hooves'. 500 British horses were ridden to death on that day alone. Nor did the end of the siege bring any relief for the 10th Hussars. Within hours they were back in the saddle, pressing on towards Paardeberg and a dramatic skirmish in which the cavalry raced the Boer forces to protect the British artillery at Gun Hill.

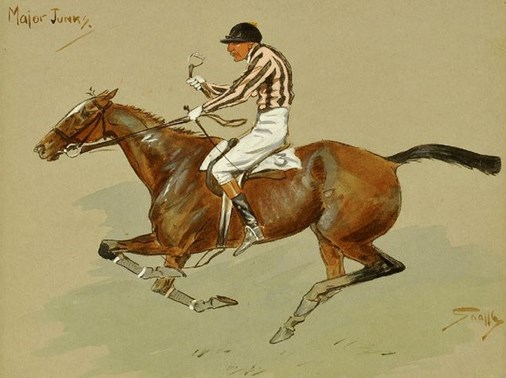

Image: Junks mounted in uniform

Hughes-Onslow's time in South Africa was nearing an end. In the summer of 1900, and after 6 months of constant warfare in unforgiving terrain, he 'was seized with typhoid and rheumatic fever, and narrowly escaped with his life'. He was taken to the military sanitorium at Wynberg, from where he sent a telegram home to say he was returning to England on sick leave.

Peace between wars: 1903–1914

Hughes-Onslow disembarked from the SS Britannic at Southampton on 22 July 1900. On returning to full health he took command of the regimental depot in Hounslow, training men for the service squadrons. As an unrivalled judge of a horse, his duties also required him to find remounts for the cavalry. Photographs have survived of a trip he made to Hungary and Croatia in February 1902 in which he is seen assessing animals for service with his regiment.

Image: Croatia, 1902

The following January, after almost 21 years' service, he retired from the army. He soon returned to his winning ways in the saddle. The year 1903 brought him great acclaim, when he rode Marpessa to victory in the Grand Military Gold Cup. His list of winners is impressive. Apart from the Grand Military Gold Cups, he won the Indian Grand Military and Ireland's Grand Military. He rode the winners in Ireland's most prestigious steeplechase, the Conyngham Cup, 3 times, the Maiden Military Steeplechase 5 times, the Melton Ladies Plate 3 times in 4 years and the Melton Ladies Purse 6 times in 9 years.

Image: Maid of the Forest

Whether under rules, or in point-to-points, he won steeplechases, and handicaps relentlessly during a 30-year career. In Gentleman Riders: Past & Present (1909), the authors wrote of him:

Of the military men riding in recent years, not one, so far as we are aware, can boast of a career in the saddle extending over so long a period, and certainly not one more successful than that of the gallant officer.

Image: Cimbric 1912

His stature was such that, when the celebrated artist Charles Payne – better known as Snaffles – painted the six top jockeys of the day, 'Major Junks' was amongst them. Snaffles showed him riding to victory while holding a stirrup in his right hand.

Image: Snaffles print

This is believed to be in reference to an incident reported by The Grantham Observer as taking place in the Melton Ladies Purse in 1912:

..... a horse stirrup-leather broke a mile from home and, seizing the stirrup, the gallant Major rode home waving it in the air, a feat which the crowd recognized with vociferous cheering.

The Great War

In 1914, and in spite of being retired from the Army for over a decade, Arthur Hughes-Onslow knew where his duty lay. 'Immediately upon the outbreak of war,' reported the Grantham Journal, he 'placed his services at the disposal of the War Office and was appointed a Remount Officer based at Southampton.' [1]

As a Remount Officer, his role was to find and prepare horses and mules for the war. The term used was 'impressment', but effectively this meant seizing the animals – a form of press gang for horses. For a man who had already been through two brutal campaigns and who knew what lay ahead for the animals he was taking, it must have been hard to bear. He was given command of Advanced Remount Depot Number 1, in Le Havre.

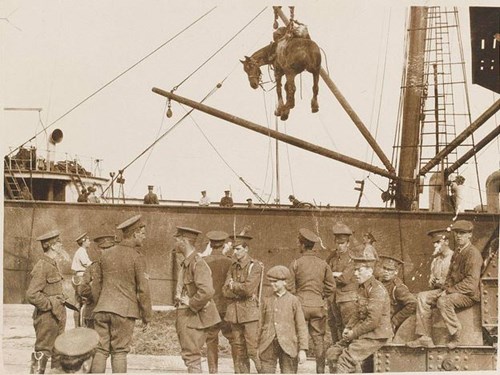

Image: Unloading horses at Boulogne, c1915. Image Courtesy of The National Army Museum, NAM. 2007-03-7-55

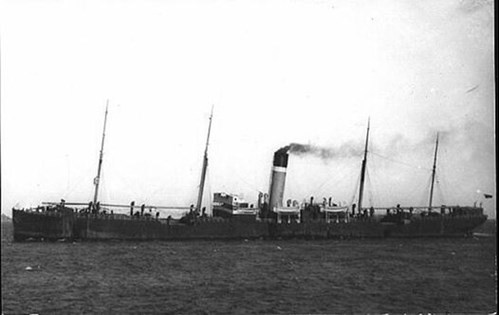

On 8 August 1914, 4 days after war was declared, Junks made his will. 9 days later, with the British Expeditionary Force gathering on the Continent, Arthur Hughes-Onslow left England for the last time, on a troopship bound for France. On 17 August 1914, on board the SS City of Edinburgh, he shot himself.

Image: SS City of Edinburgh

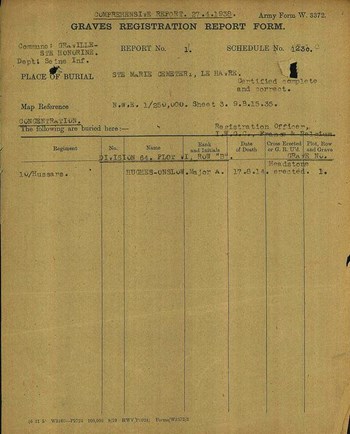

His death, one of the first fatalities among the British Expeditionary Force in the Great War, was widely reported, but the circumstances were not made public. Nor were they revealed to his family. The Government's Press Bureau announced the news alongside two victims of a car accident. Obituaries talked of his 'collapse', of his 'falling ill', but not of his suicide. He was buried in Sainte Marie Cemetery, Le Havre. (Grave reference: Div. 64. VI. B. 1.)

Image: Graves Registration Form (courtesy CWGC)

Image: Ste Marie Cemetery, Le Havre

In August 1914, Hughes-Onslow's son Geoffrey, was a midshipman on the battleship HMS Vincent, on patrol in the North Sea. In his diary, Geoffrey tells how he was summoned from watch to the captain's cabin, where the news of his father's death was broken, the message stark and short on detail. 'My God, this is hard to bear,' he wrote. While the newspapers paid glowing tribute to the military and sporting hero, Geoffrey's diary records his struggle to come to terms with how his father, a fit and vigorous 51 year-old, could have died so unexpectedly. A week later, he wrote that he had:

..... at last heard details of my dear Father's death which occurred on the City of Edinburgh when she was alongside at Le Havre. Death was caused by a broken blood vessel and was instantaneous. How often have I heard my Father pray for a sudden death when his time should come, for he always dreaded old age and inability to participate in the sports he loved, and played, so well.

It was several years before Geoffrey discovered the truth. After the war ended, his attention turned to running the family estate. It was the convention at the time that death duties were waived for the families of those who had died during the war, so the arrival of a tax demand was both a shock and a threat to the viability of the estate. It was only when the family questioned why the demand had been made that they found out what had happened.

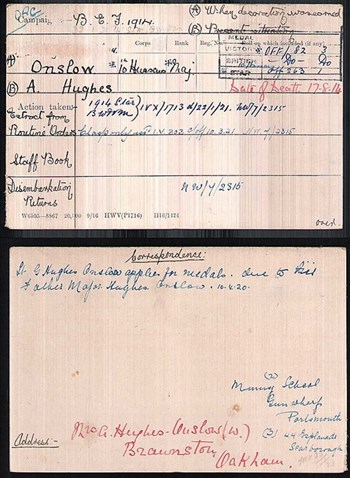

In 1921, after pressure from the family, Arthur was awarded the campaign medals due to those who had served in the Great War and the Death Plaque – given to the next of kin of all who died in active service in the war – was sent to his widow.

Image: Medal Index Card (WFA)

Although the news was dominated by the war on the continent, most papers found room to report Arthur's death. Several ran obituaries. Amongst them, the Daily Telegraph described Arthur Hughes-Onslow as 'a sportsman and a gentleman in the truest sense'. The Sporting Times wrote:

As gallant a soldier as ever fought his country's battles; as plucky a rider as ever charged an oxer. Bon-garcon all round, in fact. The name of Hughes-Onslow will remain green in the memory of those who knew him and swore by him, long after that of many a man greater than himself has faded out of recollection.

In his journal Geoffrey wrote:

God knows what I would have given for the power to add another thirty years to the life of one of the finest gentleman and finest sportsmen that has ever lived.

Image: Capt Hughes-Onslow

[1] Many of the Remount officers were drawn from the landed gentry, masters of foxhounds and others who had experience with horses in civilian life, thus avoiding withdrawing Army officers from their normal duties.

Article by John Fergusson, with additional material and images by David Tattersfield (unless otherwise shown).