McCudden meets the Red Baron

- Home

- World War I Articles

- McCudden meets the Red Baron

Whilst Manfred von Richtofen (the ‘Red Baron’) is the most famous flying ‘ace’ of the First World War, there were numerous others who are perhaps less well known among the general public. For instance René Fonck and Georges Guynemer from France and Willy Coppens from Belgium. There is also Edward Rickenbacker and Frank Luke Jr. from the USA Billy Bishop and Raymond Collishaw from Canada and Robert Little from Australia. South Africa’s Andrew (Anthony) Beauchamp-Proctor should also be mentioned.

British Aces include Albert Ball, Edward ‘Mick’ Mannock and James McCudden.

Getting to grips with the numbers of enemy aircraft shot down by these aviators is contentious. There is a degree of controversy about whether Billy Bishop or Mick Mannock had the highest score of any British Empire First World War fighter ace: combat reports and claims of both sides are full of errors (often accidental) and duplicated claims. A Canadian made documentary in the 1980s resulted in an inquiry by the Canadian government in 1985. The Standing Senate Committee criticized the documentary, saying it was an unfair and inaccurate portrayal of Bishop: the politicians were unable to confirm that Bishop's claims were valid, and so recommended that the film be labelled as docu-drama

Some of the claims by von Richtofen are also difficult to reconcile, but one in particular is intriguing. It is possible that one combat by the Red Baron which resulted in him claiming his 15th victory in December 1916 is not only dubious but also was possibly one of the very rare occasions two ‘ace’ flyers met.

Above: Manfred von Richtofen, the Red Baron

James McCudden

Although by no means a novice, Sergeant James McCudden in December 1916 had only one aerial victory to his name. He had started the war as a ‘regular’ in the fledgling Royal Flying Corps. As an air mechanic he was well regarded by his comrades in 3 Squadron.

Above: McCudden indulging in his other engineering interest: motorcycles. Image taken in 1913 at the RFC manoeuvres.

In November 1914 he volunteered to undertake ‘observer’ duties and (armed with a rifle) flew his first combat patrol. McCudden was promoted to corporal and then sergeant in April 1915, just after his 20th birthday. Only a few weeks later, on 2 May 1915, his brother William was killed in a flying accident in the UK. “This was a bad blow for me,” James wrote, “…and I felt his loss very keenly indeed.”

McCudden’s success as an observer led him to be made a full time observer and whilst the ground crew’s loss was the flying crew’s gain, this was just the start of his short but distinguished career. McCudden received the French Croix de Guerre in January 1916 for his success as an observer, and made an application to become a pilot. This was approved and (after promotion to flight sergeant) he returned to the UK to train. He was clearly a ‘natural’ as he was invited to fly solo after only four hours of dual instruction. After receiving his pilot’s certificate in April 1916 he was retained at home for a period as a flying instructor.

It is likely that he was delighted to learn that in July he was assigned to No. 20 Squadron. The squadron flew two-seat F.E.2bs in France. More good news was to follow when a month later he was transferred to 29 Squadron, which was equipped with the Airco D.H.2, a rotary-powered pusher but nevertheless a ‘fighter’.

This was “a very cold little machine,” McCudden was to write, “as the pilot had to sit in a small nacelle with the engine a long way back…no warmth from it at all.”

Above: still from 'Rise of Flight DH2 versus Albatros D11' on youtube

Initially James and his squadron flew escort for bombers, but also attacked observation balloons. On 6 September 1916, he encountered a German two-seater near Houthem-Gheluwe, Belgium. Closing to 400 yards, “I opened fire,” he was to write later.

“I fired one drum of Lewis at him, and he continued to go down while I changed drums. I then got off another drum and still got no reply from the enemy gunner, but the German was going down more steeply now….”

The victory, his first, was confirmed the following day.

The Red Baron

Richthofen scored his first confirmed victory when he shot down 2/Lt Lionel Morris and his observer Tom Rees near Cambrai, on 17 September 1916. He ordered a silver cup engraved with the date and the type of enemy aircraft from jeweller in Berlin and was to continue to celebrate like this every time he scored a victory until the supply of silver ran out .

He soon developed his tactics which would involve a dive from above to attack with the advantage of the sun behind him, with other pilots of his squadron covering his rear and flanks. His targets were more often than not the slow BE2 artillery observation aircraft that were ‘sitting ducks’ to his faster machines.

On 23 November 1916, Richthofen shot down his eleventh and most famous opponent, Major Lanoe Hawker VC, who was described by Richthofen as "the British Boelcke". It was one of the few occasions when the skills of the airmen were matched, if not the performance of the aircraft. Richthofen was flying an Albatros D.II and Hawker was flying the obsolescent DH.2. After a long combat, Hawker was shot and killed as he attempted to escape back to his own lines.

Above: An Albatros D.II

Other victories came his way during November and December: Lt Benedict Hunt (32 Squadron) was shot down (but survived) on 11 December. Hunt was flying a DH2 armed with two Lewis Guns instead of one. It is likely that the extra weight reduced the machine’s performance even more.

On 20 December the Red Baron shot down Capt Arthur Knight of 29 Squadron. Knight was also experienced (he had scored his eighth aerial victory just a few days before) and had been awarded the MC. Knight was killed in this fight (he is buried at Douchy-Les-Ayette British Cemetery).

On the same day, von Richtofen gained his 14th Victory with the shooting down of a FE2b of 18 Squadron. The pilot and observer were Lionel D’Arcy and Reginald Whiteside. Both were killed. Their aeroplane crashed very close to Jasta 2’s airfield at Pronville.

This highly accurate replica of the F.E.2b is one of only two air-worthy examples in the world (www.aviationfilm.com)

The FE2b was – like the DH2 – a ‘pusher’.

Above: a DH2

A week later was to mark the possible ‘meeting’ between the Red Baron and McCudden.

29 Squadron patrol.

Flying out of Le Hameau (also known as Izel-les-Hameaux) which was home to two aerodromes, regular patrols were the order of the day for 29 Squadron.

Above: Oblique aerial view of the RFC aerodrome at Filescamps Farm, near Izel-les-Hameaux, from the South. (IWM HU 103076)

On 27 December one of these patrols set off – comprising six DH2s – at 1.50pm. The intention was to undertake an offensive patrol between Arras and Monchy. Two of the aircraft soon had to drop out with engine problems, followed shortly by a third. The remaining three aeroplanes pressed on with the patrol. The senior pilot was Captain Harold Payn.

Above: Harold Payn, courtesy of A Fleeting Peace

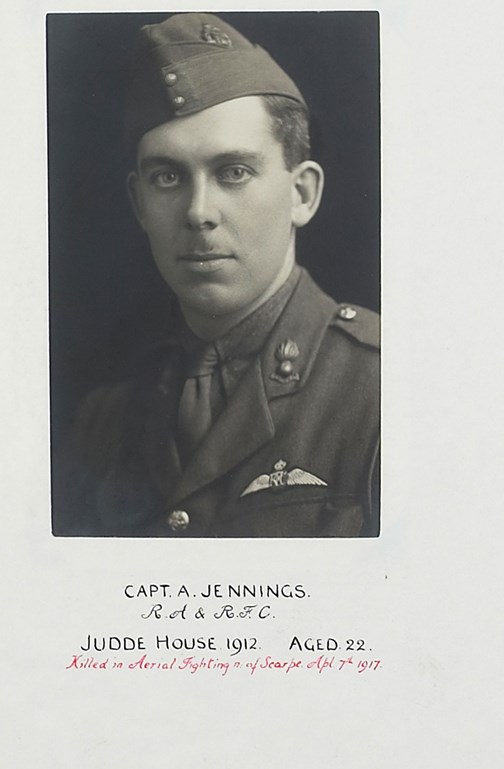

Although out ranking Sgt McCudden, the most inexperienced pilot was Lt Alexander Jennings who had only obtained his wings on 12 October 1916. No doubt he was delighted to have been posted to the famous 29 Squadron.

Above: Capt Jennings, courtesy www.tonbridgeatwar.

Jennings was promoted to Temporary Lieutenant, on 1 December. McCudden was of course experienced as an observer and had been a pilot for a number of months.

McCudden takes up the story:

We left the ground at about 2pm and crossed the lines at 10,000 feet near Arras, and patrolled north and south about a mile east of the lines. The Nieuports were further east and much higher. About 3pm I saw several Huns coming up off their aerodrome at Croisilles, on which we could look right down. They very soon got our height and then flew parallel to us, gradually coming nearer.

Above: Still from 'Rise of Flight DH2 versus Albatros D11' on Youtube > https://youtu.be/BL0WY51vkJs

By the time the Huns had got so close to us that we could see their crosses, there were only three de Havlands left, Capt Payn, Lt Jennings and myself, and very soon one of the Huns came near enough to our leader to be fired on by us. As soon as Capt Payn chased this Hun, another dived on his tail, so Mr Jennings dived at this one, and then two went after Jennings and made him throw his machine about live anything to avoid their fire. Indeed Jennings looked like [he was] having a bad time.

Above: still from 'Rise of Flight DH2 versus Albatros D11' on youtube

I now fired at the nearest Hun who was after Jennings, and this Hun at once came for me nose-on, and we both fired simultaneously, but after firing about twenty shots my gun got a bad double feed [it had jammed] which I could not rectify at the time as I was now in the middle of five D.1 Albatroses, so I half rolled. When coming out I kept the machine past vertical for a few hundred feet and had started to level out again when ‘cack, cack, cack, cack’ came from just behind me, and on looking round I saw my old friend with the black and white streamers again. I immediately half rolled again, but still the Hun stayed there, and so whilst half rolling I kept on making headway for our lines, for the fight had started east of Adinfer Wood, with which we were so familiar on our previous little joy-jaunts.

I continued to do half-rolls and got over the trenches at about 2000 feet, with the Hun still in pursuit, and the rascal drove me down to 800 feet a mile west of the lines, when he turned off east, and was shelled by our AA guns.

I soon rectified the jam and turned to chase the Hun, crossing the trenches at 2000 feet, but by this time the Hun was much higher, and very soon joined his patrol, who were waiting for him about 5000 feet over Ransart.

Von Richtofen’s version

At 4.15pm (German time was an hour ahead to this is actually 3.15pm British time) five planes of our Stafel attacked enemy machines south of Arras. The enemy approached our lines but was thrown back. After some fighting I managed to attack a very courageously flown Vickers two-seater. After 300 shots, the enemy plane began dropping, uncontrolled. I pursued the plane up to 1000 metres above the ground, Enemy plane crashed to ground on enemy side, one kilometre behind trenches near Ficheux.

Post war analysis

The problem with von Richtofen’s claim is that he is referring to a FE2b (two seater) not a single seater DH2. However, as noted above they are somewhat similar being ‘latice tailed’.

Analysis of British losses on this day has revealed that a FE2b was indeed lost, but this was much further to the north near Sailly and this was at 9.30 in the morning. Another dogfight took place near Zonnebeke but this is too far away to be remotely possible (the FE2b that came down was also on fire – which is another reason this can be discounted).

For some historians, the von Richtofen ‘victim’ here has been regarded as Capt JB Quested (pilot) and Lt HJH Dicksee (observer) who were forced down inside British lines near Wancourt (12kms east of Ficheux). The problem with this, however, is that Quested and Dicksee were brought down at 11.20am (British time) probably after clashing with Jasta 1.

If the above possibilities are discounted, and the identification of the ‘two seater’ is taken with a pinch of salt, the location and timing of the fight between the three DH2s and von Richtofen makes it a strong possibility that the two parties were talking about the same fight.

Of course , von Richtofen claims he saw the British aeroplane crash to the ground. But he had left the fight (by his own admission) at 1000 metres. It is possible that he ‘assumed’ the crash as he thought the British aircraft was out of control (if it was McCudden, clearly his superb flying had made it appear he was out of control when in fact he was avoiding his opposite number due to having a jam in his gun). It is likely von Richtofen broke off the fight to avoid fire coming up from the British Anti-aircraft guns. This, together with the fact he was on the British side of the lines, was not part of his report.

Correction of McCudden’s account.

McCudden, in his book, implies that the aircraft climbing from Croiselles were those that attacked his small formation. Howver, these would have been Fokker D1s of Jasta 12 (their aerodrome was at Reinourt, just to the east). Von Richtofen’s Jasta 2 flew out of Pronville, just to the south east of Reincourt.

Conclusion

We will never know for certain, but one reading of the various reports suggests that James McCudden – one of the most famous British Aces of the war had a very narrow escape.

James McCudden was commissioned as a 2/Lt a few days later on 1 January 1917.

After eight months in combat and over 100 patrols, McCudden returned to the UK at the end of February having become an ‘ace’ with five enemy aircraft to his name. He was awarded the Military Cross and in June, promoted to captain. He was to be awarded a Bar to his MC and a DSO and bar to go with his Military Medal and Croix de Guerre. Finally, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

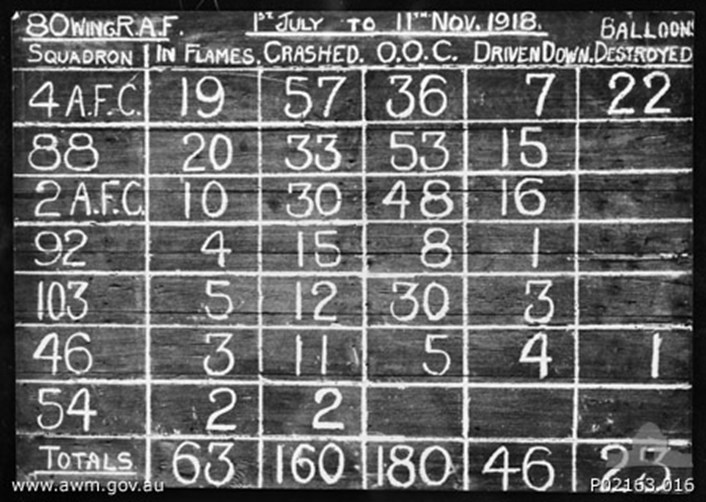

Above: A scoreboard listing the claims for aircraft destroyed by No. 80 Wing between July and November 1918.

In July 1918 he was promoted to Major and assigned to command 60 Squadron but was killed aged 23 in a flying accident en route to his new squadron. He is buried at Wavans Britsh Cemetery.

Above: James McCudden, circa 1918

McCudden's headstone at Wavans British Cemetery

Of the others in the fight on 27 December 1916, Jennings was killed a few months later on 7 April 1917, when he and another officer were attacking German captive balloons over the German lines. During the attack they were surprised and brought down. Initially reported missing, it was not until September that notification was received via Germany that stated that he was killed.

Harold Payn survived the war to become a test pilot in the 1920s

The McCudden family lost heavily in the war. James - killed in the flying accident in July 1918 survived longer than his two brothers. As recounted above, William McCudden was killed in a flying accident in May 1915 and a third brother, John was killed aged 20 in March 1918 whilst serving with 84 Squadron.

Article by David Tattersfield,

Vice Chairman, The Western Front Association

Citation for McCudden's Victoria Cross

An extract from "The London Gazette" No. 30604, dated 29th March, 1918, records the following:

"For most conspicuous bravery, exceptional perseverance, keenness and very high devotion to duty. Captain McCudden has at the present time accounted for 54 enemy aeroplanes. Of these 42 have been definitely destroyed, 19 of them on our side of the lines. Only 12 out of the 54 have been driven out of control. On two occasions he has totally destroyed four two-seater enemy aeroplanes on the same day, and on the last occasion all four machines were destroyed in the space of 1 hour and 30 minutes. While in his present squadron he has participated in 78 offensive patrols, and in nearly every case has been the leader. On at least 30 other occasions, whilst with the same squadron, he has crossed the lines alone, either in pursuit or in quest of enemy aeroplanes. The following incidents are examples of the work he has done recently:- On the 23rd December, 1917, when leading his patrol, eight enemy aeroplanes were attacked between 2.30 p.m.. and 3.50 p.m. Of these two were shot down by Captain McCudden in our lines. On the morning of the same day he left the ground at 10.50 and encountered four enemy aeroplanes; of these he shot two down. On the 30th January, 1918, he, single-handed, attacked five enemy scouts, as a result of which two were destroyed. On this occasion he only returned home when the enemy scouts had been driven far east: his Lewis gun ammunition was all finished and the belt of his Vickers gun had broken. As a patrol leader he has at all times shown the utmost gallantry and skill, not only in the manner in which he has attacked and destroyed the enemy, but in the way he has during several aerial flights protected the newer members of his flight, thus keeping down their casualties to a minimum. This officer is considered, by the record which he has made, by his fearlessness, and by the great service which he has rendered to his country, deserving of the very highest honour."

Sources:

Under the Guns of the Red Baron Norman Franks, Hal Giblin, Nigel McCrery

Flying Fury: Five Years in the Royal Flying Corps James McCudden