Royal Automobile Club Volunteer Force 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Royal Automobile Club Volunteer Force 1914

In August 1914 the British Expeditionary Force embarked for France and was considered the most professional army ever to have left these shores. Also on board one of the many vessels leaving, the SS Gloucester Castle, were twenty five civilian motorists and their cars, all members of the Royal Automobile Club.

Above: The Royal Automobile Club, Pall Mall, London

They had placed their services at the disposal of the B.E.F and were now destined to drive officers of the General Staff and Cavalry Division as required. Army Routine Orders advised: they are authorised to draw a daily rate of 10 francs per diem with effect from 23rd August for the use of their car in addition to free rations and petrol. The sum to be paid weekly in arrears by the Field Cashier on claims signed by a responsible officer of the branch of the Staff using the car. Branches were then to render to the Field Cashier a nominal roll of the owners of the cars employed by them showing the description and horsepower of the car and will notify casualties as they occur. The drivers wore a khaki uniform with no badges other than a R.A.C Brassard on an armband. Not surprisingly some of them were to be suspected of being spies and were placed under arrest. They very quickly discovered that they had volunteered for journeys which could be fraught with danger.

One such driver wrote

"Arriving at Havre we were all motored to Amiens where we were drafted to different Divisions. I got attached to the Headquarters Staff and went straight away to join the column at Etreux. The next day owing to the sudden advance of the enemy we found ourselves in Landrecies, the place in a great state of excitement owing to the fact that the Germans had suddenly entered the town. (1) So great was the congestion of refugees, artillery baggage wagons and troops that we had to leave the car for a moment and take a rifle. For a time the Germans were apparently beaten off and we attempted to get back to Etreux to stop the column. It was pouring with rain and pitch black. The state of the roads was terrible and I took a side slip and went into a ditch, breaking up the car. Well here was a pretty kettle of fish. However I had to do the best I could. Unfortunately for me our troops did not come back on the road where I was. After waiting for some time I decided to walk in the direction of Etreux, which was about eight miles away . When I arrived at Lagrosse being very wet and exhausted I stopped and was immediately surrounded by the villagers who were in a fearful state of panic as they had heard that the Germans were on the outskirts of the village. After resting a while I proceeded to Etreux and the next day went to our Headquarters to get permission to go back to Landrecies to rescue my car not knowing that the Germans were actually in possession of the town . As I was only in khaki with no distinctive badges of any kind the officer immediately suspected me for a spy and I was placed under arrest. It was only with great difficulty that my identity was accepted. After that I came along with troops as far as Compiegne and eventually boarded a French troops train as far as Criel and then got on an artillery train to Paris without any baggage or money but luckily I came into contact with General Pau and was fortunate enough to secure a 40 Hp Hispano - Siuza and rejoined my Division . Since then most days I have averaged over 100 miles a day and although I have been under shellfire and moving about between troops the car has not been touched and has never once involuntarily stopped running. The Tommies call the car the Silver Grill because of its silver fittings."

Mr Westcott has the satisfaction of being the only motorist to drive his car up to the Soupir trenches in the valley of the Aisne, his mission there being to deliver the Daily Mail to the troops.

This report appeared in the R.A.C Club Journal of November 13th 1914. The last paragraph alone gives some indication of the courage of these extraordinary men as the road up to trenches on La Cour de Soupir was under frequent shellfire by the Germans. It was bad enough for the troops to have attempted to use the road let alone unarmed civilian drivers.

Another of the drivers, Toby Robinson, was reported as follows

"To Paris with an RAC driver named Green (2) who was connected with the Orient Line of Steamships and who had been a private in the Yeomanry in the Boer War. Toby's car was most unsuitable for the trip having neither hood nor windscreen but evidently there was something wrong with Green's rather luxurious hooded two seater. Toby couldn't remember what the trouble was with Green's car only that it had a rather splendid bullet holes in the rear panels. On the wet journey to Paris Green told Toby how he had acquired the bullet holes."

A few days earlier he had been driving a Staff Officer, Major Arthur Henderson (3) and they had been out all day when returning in the dark they had to pass a village in which there had been a French barrier and picket when they had passed in the morning. Their car was accompanied by a motor cyclist and together they approached the barrier stopping when challenged by a sentry who asked for the password. When the sentry got closer they observed that he was a German. Henderson promptly drew his revolver, aimed it point blank at the sentry's head and pulled the trigger. The result was a loud CLICK . The sentry jumped into the air with astonishment and terror but had enough sense to yell for help and at the same time started to fire at them. Green crashed the car into gear, let in the clutch and put his foot on the floor. The poor motorcyclist was shot at once but the other two got away with bullet holes in the car being the only damage. Green in his excitement had managed to drive away in first gear and had not changed up in his panic, consequently drove some distance flat out at 15 mph with the engine threatening to shake itself into pieces.

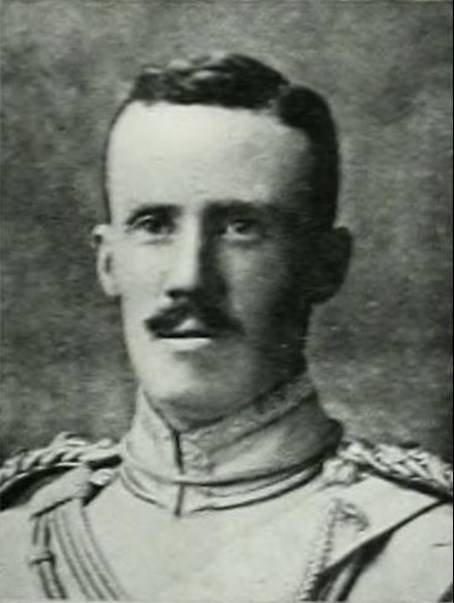

Major Henderson was killed on September 12th whilst looking for General Gough, having been told that the General had crossed the Aisne.

Above: Major Arthur Henderson

There is a classic account of the dangers encountered by another RAC volunteer, Frederic Coleman, an American who wrote of his experiences in his book From Mons to Ypres with French. He drove for the Brigadier General H B de Lisle, commanding the 2nd Cavalry Brigade and it gives a fast moving account of the operations he had to undertake during the early part of the war. He had a great admiration for the British Army. Other drivers must have encountered similar dangers and it speaks volumes for the patriotism of these men who were daily willing to risk their lives. In October 1914, a further forty six drivers were recruited with their cars for service with the Naval Division at Antwerp.

The Royal Automobile Club issued a 30 page booklet after the war concerning the service of the club and of its members - Imperial Service 1914 until 1919. Its final pages show a Roll of Honour which contains the names of 226 members of the club and 24 of it staff. The members list contains 3 Victoria Cross and 12 Distinguished Service Order awards.

Notes

1. August 25th/26th 1914

2. Mr S V Green

3. Major Arthur Francis Henderson, 27th Light Cavalry Division Indian Army. Appointed GSO2 to General John Gough. He was killed near Conde bridge on September 12th 1914. His roadside grave was lost and he is commemorated on the Indian Memorial at Neuve Chapelle

Mr Westcott's report was printed in the Royal Automobile Clubs Journal November 13th 1914

Mr Green's article was taken from - Adventures on the Western Front 1914-1918 by A Rawlinson.