The Air Raid on Chatham Drill Hall 3 September 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Air Raid on Chatham Drill Hall 3 September 1917

On 3 September 1917, the Chatham Drill Hall, then a glass roofed building, was being used as a temporary overflow dormitory for sailors and there were 698 men asleep or resting in their hammocks in the Drill Hall. The Drill Hall formed part of the Royal Navy’s HMS Pembroke barracks at Chatham.

Above: the main gate to HMS Pembroke thought to have been taken between 1905 and 1910. Photo – Medway Archives Centre

The Drill Hall at HMS Pembroke in Chatham was completed by 1902 and, as its name suggests, was constructed to provide an indoor space in which the exercise and training of navy personnel could be undertaken during inclement weather. Often referred to as the ‘Drill Shed’ it was also used variously as an overflow barracks, exhibition centre, naval store (for rum, clothing and general supplies) and building materials warehouse. The drill shed is about 250 yards long and 25 yards wide; solid brick walls, with offices along one side… It has a glass roof, quarter of an inch thick.

Above: the Drill Hall at Chatham

In September 1917 the problem of housing the men at HMS Pembroke had been further exacerbated by two unanticipated events: firstly, the men who had been earmarked to join the battleship HMS Vanguard had been forced to remain at the barracks, after she had been sunk at Scapa Flow in July 1917. Secondly, an outbreak of 'spotted fever' (epidemic cerebro-spinal meningitis) in the barracks meant that the sleeping accommodation had to be increased in an effort to avoid further infection.

At 9.30 p.m., five Gotha G.V. Bombers left Belgium. Since the greatest loss of the bombers was during the daylight raids, the decision wasmade to carry out a night-time attack – this would be one of the first of the First World War 'moonlight raids'.

Above: a Gotha G.V. aeroplane

One of the bombers encountered engine problems and had to return to their airbase but the remaining four carried on and passed over the Isle of Sheppey at around 11.00 p.m. where they followed the River Medway towards Chatham. As this was the first night-time raid, the Medway Towns were unprepared and the whole of Chatham was illuminated with none of the anti aircraft guns prepared for attacks.

The Leeds Mercury would later report:

“No warning of the approach of the invader was given, and no-one appears to have seen it. The droning of its engine, however, was distinctly heard. The raid was assisted by a singular coincidence. Monday night had been selected for anti aircraft practice and because of that policemen were actually going through the streets advising people not to be alarmed when they heard the guns firing at the very moment that the raider began his attack”.

Other reports suggest that a practice alert had been carried out earlier in the day within the town, and when the aircraft were finally spotted and an alert sounded, many people ignored the warning believing it to be another practice drill.

The Drill Hall suffered a direct hit. The bomb shattered the glass roof, sending dangerous shards of glass flying through the drill hall before exploding when they hit the floor. The clock on the drill hall tower stopped at 11.12, giving the exact time the bomb exploded. The men asleep or resting inside had little chance of survival, those that were not injured from the explosion were cut to pieces by the falling pieces of glass from the roof.

Rescuers subsequently spent 17 hours looking through the rubble. By the end of the raid the total number of dead stood at 98, but this would increase as injured men later succumbed to their injuries. Accounts from eyewitnesses were gruesome - one, Gideon Gardner, recorded:

“Some had never woken up; apparently the shock appeared to have stopped their hearts. They were stretched out, white, gaunt, drawn faces, with eyes nearly bolting out of their heads. Others were greatly cut up, mangled, bleeding and some were blown limb from limb”.

Ordinary Seaman Frederick W. Turpin went to the scene to help with the wounded. He recorded what happened in his notebook:

"It was a gruesome task. Everywhere we found bodies in a terribly mutilated condition. Some with arms and legs missing and some headless. The gathering up of the dismembered limbs turned one sick….It was a terrible affair and the old sailors, who had been in several battles, said they would rather be in ten Jutlands or Heliogolands than go through another raid such as this."

E. Cronk was also at the barracks when the bombs hit:

"The raider dropped two bombs; one in the middle of the drill shed and one near the wall of the parade ground just where the sailors were sleeping. I shall never forget that night – the lights fading and the clock stopping… we of the rescue party picking out bodies, and parts of bodies, from among glass and debris and placing them in bags, fetching out bodies in hammocks and laying them on a tarpaulin on the parade ground (you could not identify them). I carried one sailor to the sick bay who was riddled with shrapnel and had no clothes left on him. In the morning, to show that the officials could tell who was who, they had a General Pipe asking all sailors of different messes if they could identify any of the lost; it was impossible in most cases. It was one of the most terrible nights I have ever known – the crying and the moaning of dying men who had ten minutes before been fast asleep."

Officers and the surviving ratings who were able to, tore at the rubble with their bare hands in their efforts to find those lost beneath the debris of the shattered Drill Hall. The work of the rescuers continued through the night and was only completed some seventeen hours later on Tuesday afternoon.

It was a sad spectacle in the moonlight – officers and men carrying the dead bodies of comrades into buildings which had been transformed into a mortuary and the seriously wounded cases into motor ambulances which sped to the hospital - flying glass and falling debris accounting for many of the casualties.

The funerals of 98 of those killed in the air-raid were held on Thursday 6 September 1917, with the procession consisting of 18 lorries draped with the Union Jack and each carrying six coffins. These 98 men were buried at Woodlands Cemetery in Gillingham with another 25 men being interred elsewhere and later burials taking place once the ratings had been identified. All the men were buried with full military honours and were followed by a procession of marching soldiers and sailors with thousands of people lining the streets.

Above: the funeral procession on 6 September 1917. Photo IWM

Above: the Mayors of Rochester and Chatham attending the funeral of seamen killed in a raid over Gillingham in September 1917. Photo – IWM Q 54048

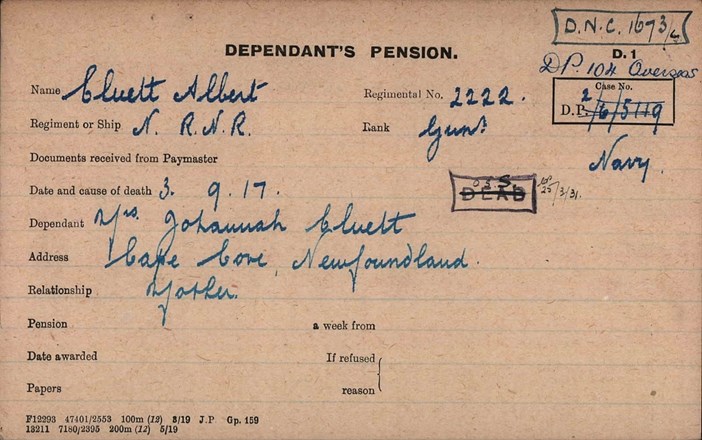

The final number of those killed in the air raid is usually stated to be between 130 and 135. Among those killed in the air raid were five Canadian sailors, four of whom served in the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve. joined up on 14 October 14, 1916, at the age of 20.

After completing basic training on board the HMS. Calypso (later renamed HMS. Britton), he was sent to Chatham, England for specialised training as a gunner. Albert was then posted to HMS. President III, a defensively armed merchant vessel, around February 1917. While serving in the Bay of Biscay, the ship came under attack from a German submarine. Soon after, the President III struck an iceberg and subsequently, some rocks at Cape Race. Albert and the rest of the crew were forced into port while the ship was repaired. Albert was granted leave to visit his family in Cape Cove, Fogo Island. After his brief leave, he returned to England where he was waiting for his orders at the Chatham Naval Barracks on September 3, 1917. He was asleep in his hammock when the drill shed was bombed in the air raid later that night, with Albert sustaining “multiple bomb wounds,” according to the Chatham Naval Hospital records, of which he died in the early hours of 4 September 1917.

Above: Seaman Albert Cluett. Photo- downhomelife.com

Above: the Pension Card for Albert Cluett. His mother received a monthly pension of $6.50.

Thomas Ginn, born February 1895, was also from Fogo Island, Newfoundland.

Above: Seaman Thomas Ginn and his headstone in Woodlands Cemetery. Photos – Canadian Virtual War Memorial

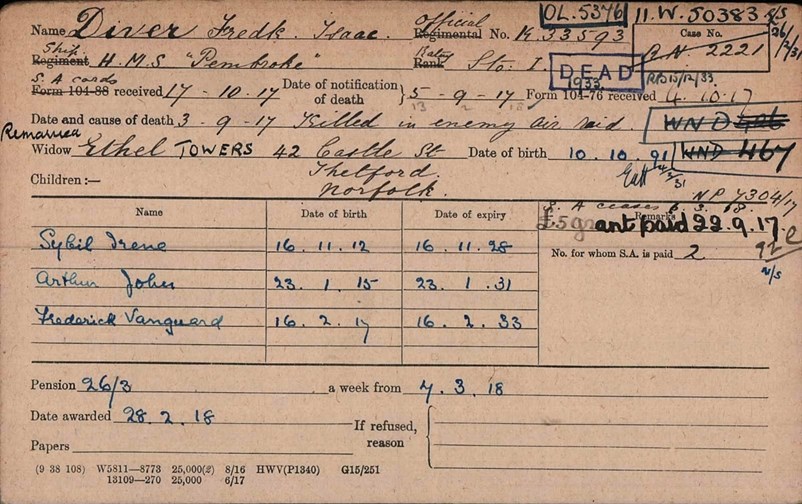

Another casualty of the air raid was Stoker 1st Class Frederick Isaac Diver, born in July 1888. He enlisted on 1 July 1916. Frederick left a widow and three children, the youngest of whom, born in February 1917, has the middle name of ‘Vanguard’ – on which ship Frederick was serving at that time. He was buried in Thetford Cemetery.

Above: Frederick Isaac Diver, and the cemetery at Thetford where he is buried.

The Pension Card for Frederick Diver explicitly states the cause of his death.

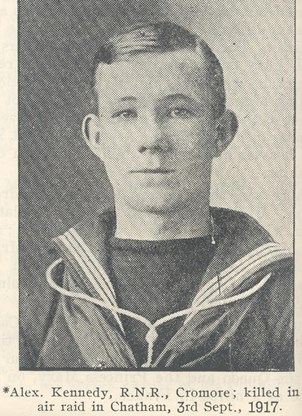

Seaman Alexander Kennedy came from the Western Isles.

Above: Seaman Alexander Kennedy. Photo – Lewismen lost in the Great War

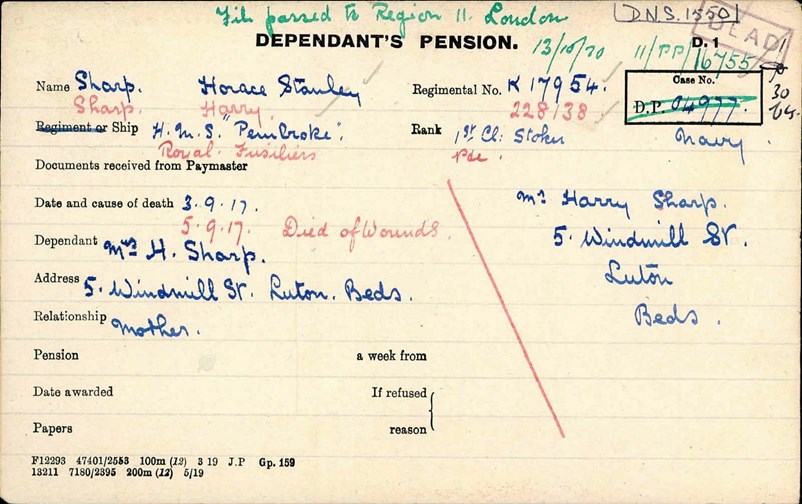

Stoker 1st Class Horace Stanley Sharp, born in 1894, was the son of Harry and Edith Sharp. He died in the air raid – and just two days later, his brother, Harry, serving in the London Regiment, died of wounds.

Above: Horace Stanley Sharp, killed in the air raid and his headstone.

Above: The Pension card also details the death of his brother just two days later.

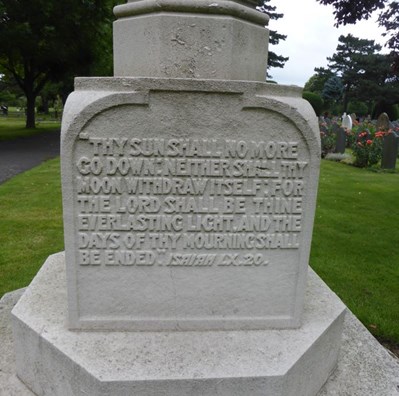

A memorial commemorating the Chatham air raid is situated in the Woodlands Cemetery.

Above: the Memorial in Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham

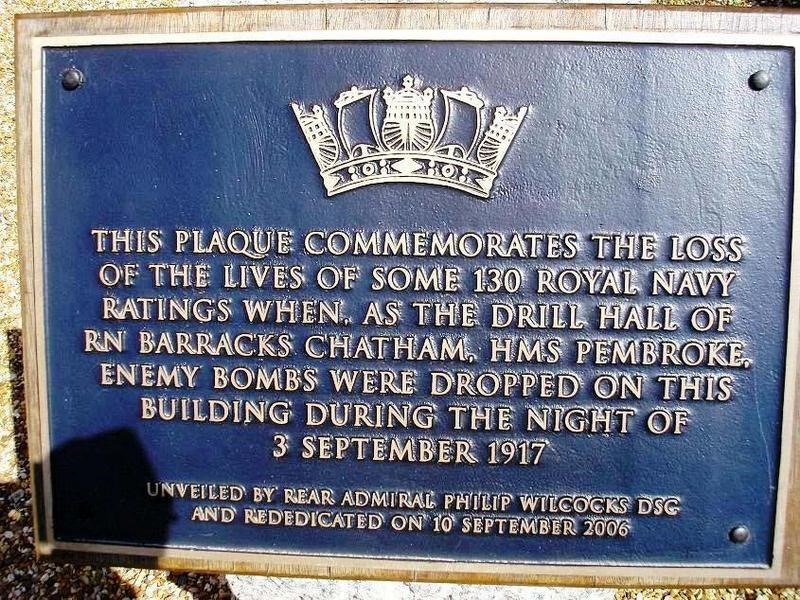

A plaque commemorating those killed in the air raid was erected at the building in 2006.

Above: the commemorative plaque. Photo - IWM

In 2003 the Universities of Greenwich and Kent acquired the Drill Shed and adjacent buildings as part of their shared campus development. In 2006, after significant refurbishment, the Drill Shed reopened as the Drill Hall Library, a shared facility for the Universities at Medway (Canterbury Christ Church University, University of Greenwich and University of Kent).

Since the restoration of the building, the anniversary of the tragedy has been marked by a short service of remembrance. On 10th September 2017, the Royal Naval Association Chatham Branch, along with the Universities at Medway, who have campuses at what is now known as Pembroke, commemorated the centenary of the tragedy.

A service and parade took place with Rear Admiral John Kingwell CBE taking the salute. Many took part including the local Sea Cadets, Royal Marine Cadets, HMS Collingwood Band, the Merchant Navy, the Royal Naval Reserves and staff and students from Canterbury Christ Church University who were dressed in health care period uniform.

Relatives of the naval personnel who perished on that night, as well as friends and local residents who attended from all parts of the UK and Canada, remarked that the event was poignant, sensitive and remembered our naval heroes with dignity.

Guests and participants were able to explore Pembroke and attend a 1917 health care exhibition. Following on from that event, it was agreed that the Universities and the RNA together would create a film to capture the vital part of local history and the commemorative event itself. This can be viewed here -

Article contributed by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Sources

East Wickham and Welling War Memorial Trust

Naval-history.net

campus.medway.ac.uk/history/

www.canterbury.ac.uk