The Baralong Incident 29 January 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Baralong Incident 29 January 1917

The Baralong was a 'three island' tramp steamer built in 1901 by Armstrong & Whitworth. She was requisitioned by the Navy in 1914 intended as a supply ship but in early 1915 was identified as a potential decoy ship. Modification works to equip her for this role, including the installation of three concealed twelve pounder guns, were carried out at Barry Docks and completed in 1915.

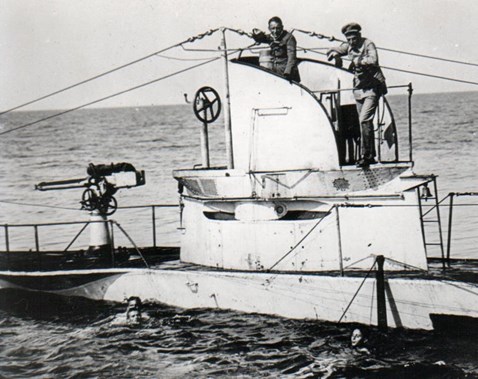

Above: the Baralong

Commanded by Lieutenant Commander Godfrey Herbert, her crew were volunteers.

Above: Godfrey Herbert

Born in Coventry, following a period at Littlejohn's School, a naval crammer in Greenwich, Herbert became a naval cadet on HMS Britannia in 1898 and in June 1900 was enlisted as a midshipman in the Navy. He spent much of his early Navy career on submarines and was second in command of the boat HMS A-4 in 1905 when it suffered a serious accident (but with no loss of life). His actions at that time were praised in the press.

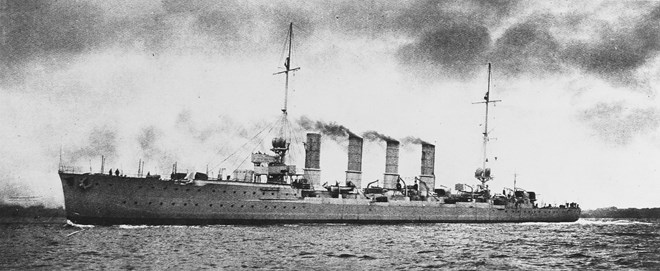

On the outbreak of war, Submarine D-5 was assigned to 8th Submarine Flotilla and patrolled in the eastern end of the English Channel during early August. Herbert’s first opportunity to strike at the enemy came on 21 August 1914 when D-5 fired two torpedoes at the German cruiser SMS Rostock, but both missed.

Above: SMS Rostock

A few weeks later, D-5 hit a mine off Great Yarmouth in the North Sea – there were only five survivors from D-5, including Herbert.

Above: the ill-fated Submarine D-5

In January 1915, Herbert was then appointed to command the Q-Ship, HMS Antwerp, formerly the Great Eastern Railways steamer Vienna, but his only encounter with the enemy was when he came across U-29 off the Scillies. U-29 successfully evaded the Antwerp (but would later be rammed by HMS Dreadnought).

Royal Navy Ordinary Seaman George Hempenstall served on the Antwerp. He has recounted his recollections of life on board the Antwerp, which he describes as a ‘nice little passenger boat’ in an interview with Peter Hart. At that time, his only civilian clothing was a Great Eastern Railway’s jersey. Describing discipline as ‘free and easy’ with ‘no standing to attention, no saluting – all that was a wash-out’, much of his time would be spent below decks.

Herbert was frustrated by the slow speed of the Antwerp, lobbying the Admiralty for a change of vessel - he identified the Baralong for his next command in April 1915, with Sub Lt. Gordon Charles Steele of the RNR as his second in command, and some of the crew from the Antwerp.

Above: Gordon Charles Steele

From April 1915, the Baralong would search for enemy U-boats in the English Channel and the Western Approaches with no success. All was not entirely well on board the ship, with discipline an issue. Herbert appears to have had a relaxed view of discipline and frequently socialised with junior officers, in contravention of naval custom. George Hempenstall, who also transferred to the Baralong recollected that there was also some tension between the Merchant Navy and Royal Navy seamen. Navy personnel were given 30/- to purchase secondhand clothes which would be worn onboard and on any shore leave. But secrecy was essential to the work of the Q Ships, and ‘runs ashore’ were eventually banned. Nonetheless, there were incidents when members of his crew swam ashore, in one instance resulting in drunkenness, brawling and imprisonment. Herbert allegedly also referred to himself as ‘Captain McBride’.

On 7 May 1915 the Baralong responded to the Lusitania’s call for help, but had arrived too late. Since then, there had been no excitement with no sightings of enemy submarines, despite the evidence of their activity. Herbert, and the crew, were growing increasingly frustrated by their lack of success.

This would change on 19 August 1915 when Baralong responded to a SOS call from the passenger liner SS Arabic which had been attacked by a U-boat. A nearby ship, the Dunsley, had also been torpedoed. The Baralong rushed to the scene but found nothing – due to an error in the SOS call the wrong position had been sent out. Meantime both ships had sunk; yet again the Baralong’s chance to engage with the enemy had been thwarted.

Above: SS Arabic, sunk on 19 August 1915 by SM U-24, with the loss of 44 lives

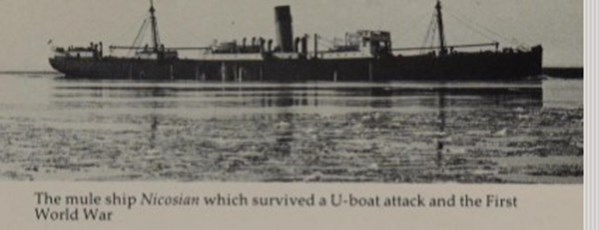

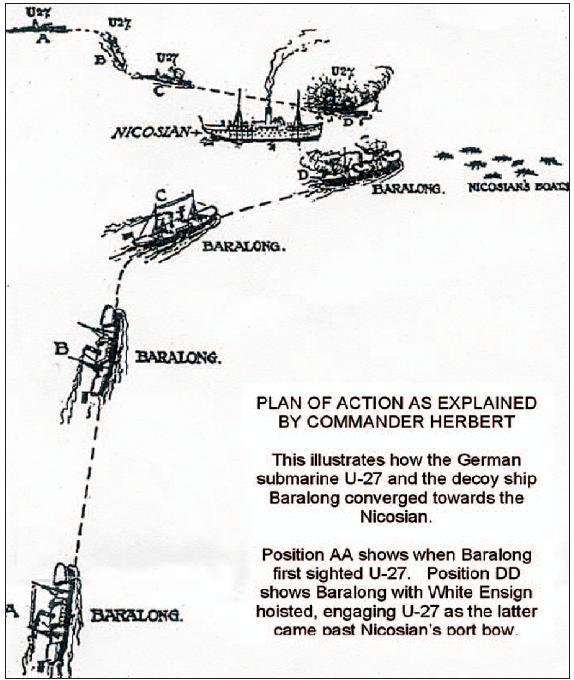

Later on the same day further messages were received the penultimate of which was ‘Captured by enemy submarine. Crew ready to leave’ followed by the last message ‘Help, help, for God’s sake, help’ which had the Baralong steaming at full speed towards the Nicosian, from New Orleans, carrying a cargo of cotton, timber, tinned meat and 750 mules for the British Army. Within twenty minutes, the Baralong had the Nicosian in sight.

Above: the Nicosian

U-27, with Korvetten-kapitan Bernard Wegener in command, had fired on the Nicosian and ordered her captain to abandon ship. The captain of the Nicosian ordered ‘away all boats’ once the crew had assembled on deck.

Above: U-27 and her captain, Bernard Wegener

Flying ‘The Stars and Stripes’ and running up the signal ‘am saving life’, the Baralong came up on the starboard beam of the Nicosian while U-27 moved out of sight. He then raised the White Ensign and when U-27 again appeared in sight the Baralong’s guns fired on her inflicting a killer blow amidships just below the waterline. The Baralong continued to fire on U-27 until the U-boat sank. Hempenstall’s account of this encounter suggests that once the Baralong was within 600 yards of U-27 there were no American flags being flown on the Baralong.

Meantime, the Nicosian had not sank, with several of the German submariners swimming towards her and shinning up ropes’ ends. Herbert ordered that they be fired upon. Only six Germans were able to board the Nicosian but they reportedly all succumbed to injuries that they had received earlier. In the end, there was not a single survivor from U-27.

Within a month of the sinking, Herbert would be gazetted with the DSO. The crew were awarded £1,000 and Sub Lt. Gordon Steele was rewarded with the rare honour of being transferred from the RNR to the Royal Navy. He would later be promoted to Lieutenant.

Despite Herbert asking the Captain of the Nicosian to ensure that his men did not talk about the events on 19 August 1915, word leaked out and it would not be long before eyewitness accounts of the sinking of U-27 would hit the press, with a five part story published in The Chicago American. The account came from one of the American muleteers on board the Nicosian and left little to the imagination, damning in the account of British actions that day, including allegations that the American flag had been flown during the action and that the German submariners had, in effect, been murdered by the British.

Inevitably, the Germans seized on the accounts of the incident published in America and the events of 19 August 1915 became the subject of German protestations of war crimes. In January 1916, the British Government released a White Paper on the incident which, when reported, would be the first that the British public knew of the affair. Several newspapers would then report in January 1916 on the ‘impudence and cunning of the Kaiser’ in raising such complaints and there appears to have been little sympathy in the press for Germany’s stance in the light of some of the events earlier in 1915.

But this would not be the end of controversy surrounding the Baralong. A few days after the incident on 19 August, Herbert was appointed to the command of E-22, with Lt. Commander Andrew Wilmot-Smith taking command of the Baralong, with most of the original crew on board.

On 24 September 1915, Baralong sighted a sinking ship, SS Urbino, with lifeboats heading away from her and nearby, U-41, under the command of Kapitanleutnant Klaus Hansen. On the day before, U-41 had sunk three ships – the Anglo-Columbian, the Chancellor and the Hissione.

Above: the commander of U-41, Klaus Hansen and the SS Urbino

The controversy around the Baralong and U-27 had not broken at this point. Hansen saw that the Baralong was flying the Stars and Stripes, and while a boat was launched from the Baralong to take papers to Hansen, the Baralong’s guns opened fire. Within seconds, U-41 plunged to the depths, with only two survivors, both of whom ended up on the Baralong.

Above: a German propaganda postcard regarding the Baralong’s role on 24 September 1915

Following the sinking of U-41, a medal was struck by the German artist Karl Goetz to denounce what was viewed in Germany as its controversial sinking.

Above: the medal struck to denounce the sinking of U-41. Photo – Collections.rmg.co.uk

After 24 September 1915, Baralong was transferred to the Mediterranean, now known as HMS Wyandra, to join the Q-ship force being established there. She continued in this role but had no further success, and in November 1916 returned to civilian service as the Manica. She would later be sold to Japan and was scrapped in 1932.

Above: HMS Wyandra

Endnote

Herbert commanded further Q-Ships during 1916, and on 9 October 1916 was appointed to the command of K-13. Known as the ‘Kalamity Class’, K-13 sank on a test dive on 29 January 1917, with Herbert in command, although he survived.

Above: the memorial in Faslane Cemetery to those lost on K-13. Photo -Helensburgh-heritage.co.uk

Gordon Steele continued to serve in the Navy after the end of the war. In 1919 he would be awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions on 18 August 1919 at Kronstadt. He would later be one of the honour guard on the return of the unknown warrior to London in November 1920.

Above: the honour guard for the Unknown Warrior’s return to Britain

Article by Jill Stewart

Hon Secretary

The Western Front Association

Sources

Tony Bridgland : Sea Killers in Disguise: Q Ships and Decoy Raiders of WW1 Naval Institute Press (1999)

Alan Coles : Slaughter at Sea: Truth Behind a Naval War Crime Robert Hale Ltd (1986)