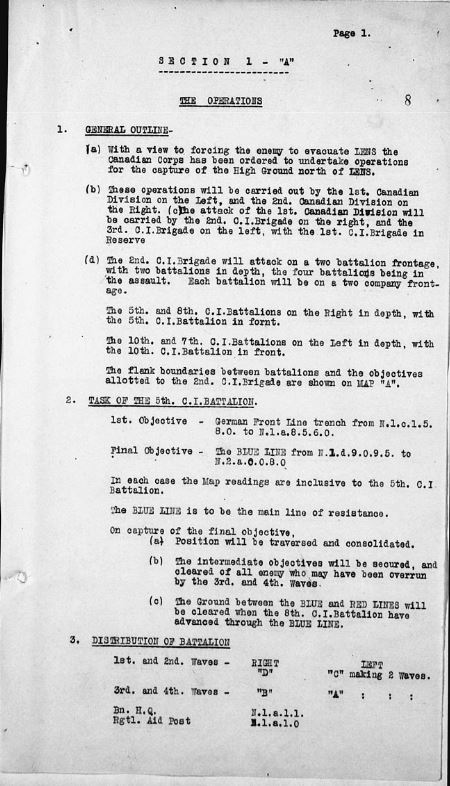

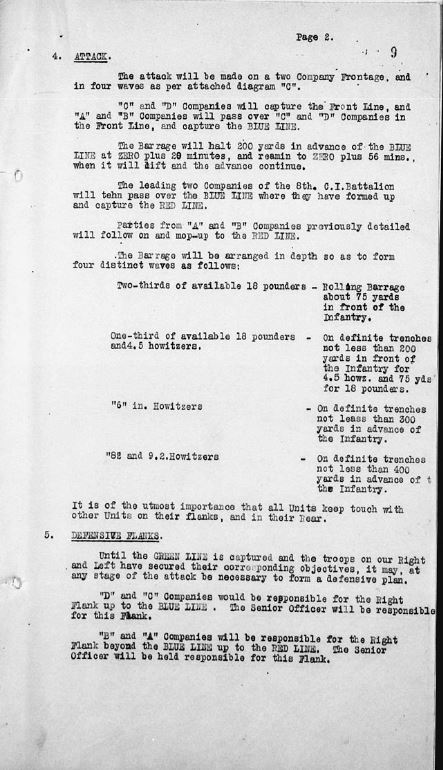

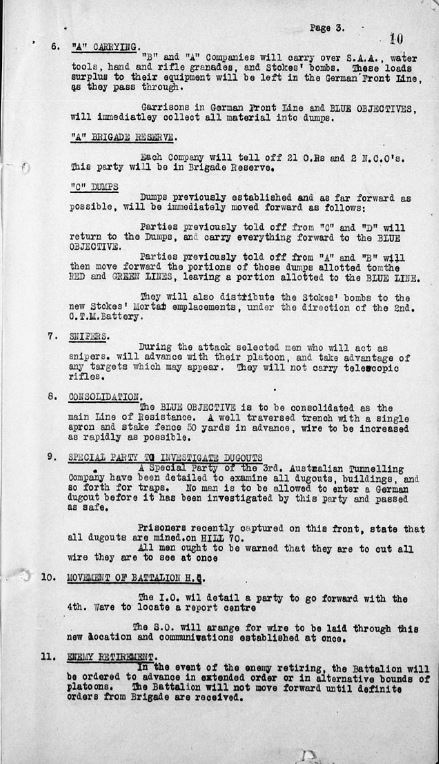

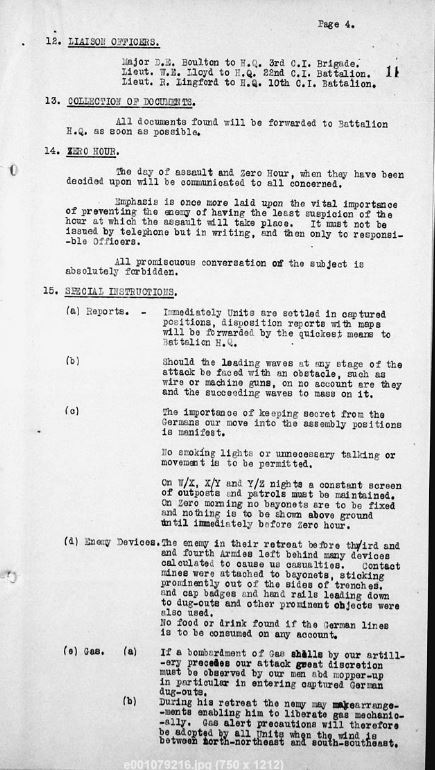

The Battle of Hill 70

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Battle of Hill 70

The Third Battle of Ypres (commonly, but inaccurately known as ‘Passchendaele’) commenced on 31 July 1917. High hopes of success soon evaporated as the attack bogged down in the mud caused by torrential rain. In an attempt to draw German troops away from the Ypres sector, a diversionary attack was planned to take place to the south in the Lens/Loos area. This assault was to be primarily conducted by the Canadian Corps plus the (British) 46th (North Midland) Division.

General Sir Arthur Currie was the officer commanding the Canadian Corps having been promoted from GOC of the 1st Canadian Division only a few weeks before. Although standing over six feet tall, Currie did not cut a heroic military figure, but his rise to become the first Canadian to lead his national contingent was well deserved as he was a highly competent soldier.

Above: Currie with Sir Douglas Haig. Currie came across as being somewhat aloof by his troops, who called him "Guts and Gaiters."

At a conference of corps commanders, Currie persuaded British First Army commander, General Horne (photo below) to make Hill 70, rather than the city of Lens, the main objective. Although he anticipated that allied losses would still be high, Currie felt that taking Lens but leaving the high ground of Hill 70 in German hands would lead to even higher casualties.

Currie was determined to try to reduce casualties amongst the all-volunteer Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). It is said that Currie’s motto was “Pay the price of victory in shells—not lives”.

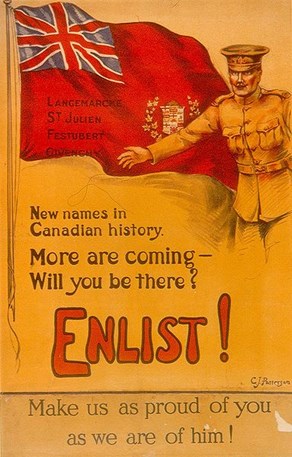

Above: A Canadian recruiting poster

Hill 70 was a superb defensive position that had been temporarily taken two years earlier during the Battle of Loos. (The Battle of Loos was the first time the British had used poisoned gas on the Western Front.) Since 1915, Hill 70’s defences had been enhanced, containing a maze of deep trenches which were protected by coils of barbed wire up to five feet in height. Machine guns and pill boxes constructed out of reinforced concrete gave further protection.

Currie ensured that the divisions under his command were thoroughly prepared for the assault. An area behind the British lines was laid out to represent the ground to be attacked and units practised extensively.

Bad weather led to the postponement of the attack from late July until mid-August. In the meantime, the ‘normal’ preliminary bombardment was augmented by the firing of 3500 gas drums and 900 gas shells into Lens. The artillery neutralised 40 out of an estimated 102 enemy batteries in the area.

Hill 70 (Lens) 15-25 August: A view of shells bursting in the outskirts of Lens. (IWM CO 1794)

The infantry assault began at 4.25am on 15 August, just as dawn was breaking. Special companies of the Royal Engineers fired drums of burning oil into the suburb of Cité St. Élisabeth and at other selected targets in order to supplement the artillery and to build up a smoke-screen. Divisional field artillery positions brought down a barrage directly in advance of the assaulting troops while heavy howitzers shelled known German strong-points.

Communications were always a problem in the Great War. One of the most effective methods of sending messages back was through the use of Carrier Pigeons. Here, two Canadian soldiers are dispensing water to pigeons.

“Canadian pigeon carriers watering the birds in captured Boche trenches on Hill 70. August, 1917.” Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

Artillery Forward Observation Officers moved forward with the infantry and artillery observation aircraft flew overhead and sent 240 calls for artillery fire by wireless. Ten battalions from the Canadian 1st and 2nd Divisions advanced up the hill. Although they took their initial objectives in just twenty minutes, the final objectives were not captured until about 5.15 pm on 16 August. One Brigadier stating “I wish to report that the fighting which took place from the crest of HILL 70 forward on this Brigade frontage was the fiercest and most bitter which the Battalions of this Brigade have experienced or ever seen.”

Above: Canadian soldiers in a captured German trench during the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917. The soldiers on the left are scanning the sky for aircraft, while the soldier in the centre appears to be re-packing his gas respirator into the carrying pouch on his chest. Dust cakes their clothes, helmets and weapons.

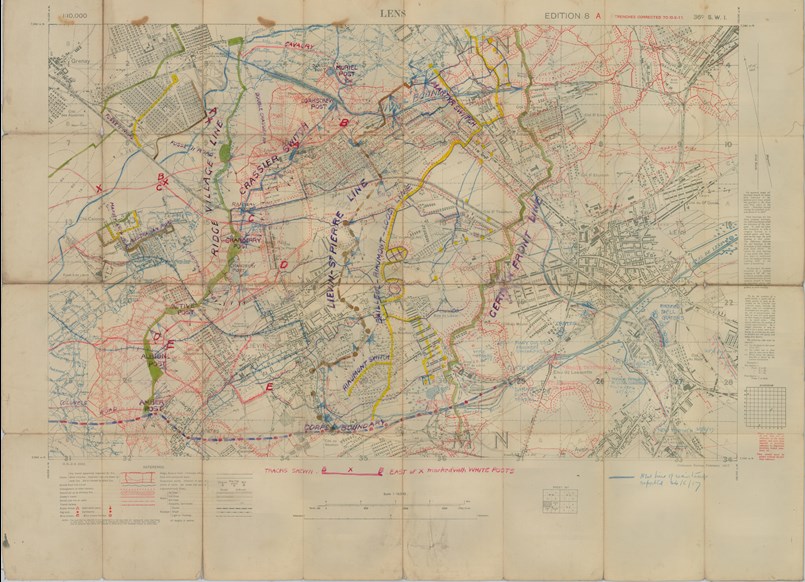

Above: A map of the area of Lens/Hill 70 (trenches corrected to 10 February 1917 (6 months before the attack). Click here for An enlargement of Lens/Hill 70.

By 9.00am the Germans commenced a series of counter attacks; over the next three days over 20 were launched, much of the German effort being focused on the Canadian artillery. The Canadian 1st and 2nd Artillery Field Brigades and the Canadian front line were heavily gassed, the Germans using a new type of gas called ‘Yellow Cross’ which contained the blistering agent sulphur mustard. Many artillery men became casualties after gas fogged the goggles of their respirators and they were forced to remove their masks in order to maintain accurate fire. German troops employing flamethrowers managed to penetrate the Canadian line before being driven out.

Above: German flamethrower in use (although not under battle conditions).

The attack on Hill 70 on 15/16 August resulted in the deaths of about 1,400 allied troops plus over 8,000 wounded (including over 1,000 gas casualties). German casualties amounted to about 30,000 including nearly 1,500 taken prisoner.

“Dressing wounded Canadians” Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

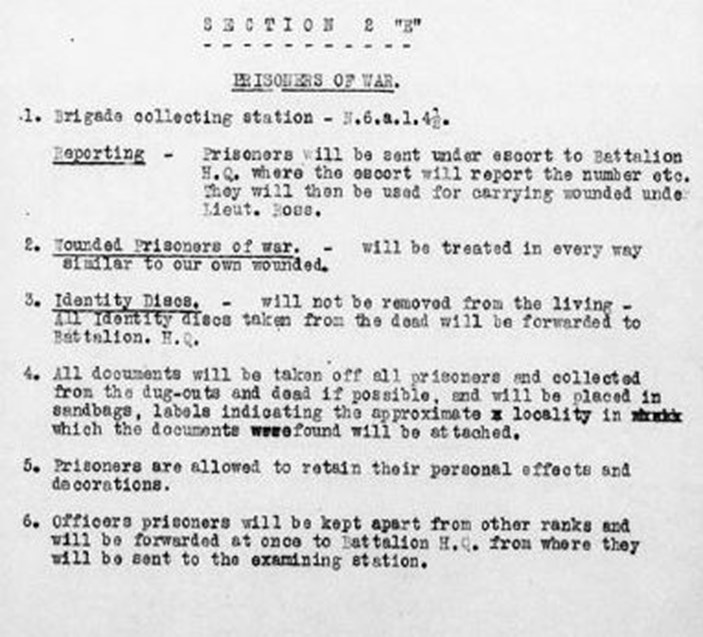

The 5th Battalion of the CEF – the battalion’s full title was 5th Battalion (Western Cavalry) – was part of the 1st Canadian Division. Taking this unit as a “typical” battalion, orders totalling in excess of four pages were issued (see Appendix 1) covering instructions from the objectives of the attack to the collection of prisoners. More detailed instructions were issued (see image, below) regarding prisoners taken – information extracted from prisoners or from papers in their possession was often the source of vital intelligence.

Invariably, the moment of capture was dangerous – there was always the possibility that a soldier’s surrender would not be accepted.

Above: In an obviously “staged” scene for the benefit of the photographer (note the onlookers getting into the photo), the nervous German captured here is being interrogated. It is believed that the officer is Major Pyman of the 5th Battalion. If the officer is Pyman, he was to survive this battle, but was killed less than a year later. Image courtesy of The Encyclopaedia of Saskatchewan

Major Colin Pyman had a distinguished war record, being awarded the DSO and bar.

Above: A group of officers of the 5th Battalion, CEF in 1918. Is Major Pyman one of these officers? Image courtesy of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group

Distinguished Service Order, Supplement to the London Gazette dated 1 October 1918:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. This officer was in charge of a raiding party of considerable importance, and the success of the operation was largely due to the thorough manner in which he had thought out and supervised every detail beforehand. He directed the operations with a courage and complete disregard of danger that inspired the greatest confidence in the officers and men under his command.

Bar to Distinguished Service Order, Supplement to the London Gazette dated 1 February 1919:

For great skill and gallantry while acting as second in command of the battalion between the 7th and 9th August, 1918, during the advance on Aubercourt. When the line became much weakened through casualties, he collected men together, and, after a vigorous fight, placed them in the gaps. He was instrumental in capturing a field gun and a number of prisoners, and on another occasion in throwing out a protecting flank, thus enabling the advance to continue. He was wounded on the 9th within fifty yards of the final objective.

Major Colin Pyman was killed on 10 August 1918 and is buried at Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery.

Prisoners were collected and marched to the rear under close escort. All of this had to be planned to the smallest detail by the often maligned 'red tabs' on the staff.

Above: German prisoners being marched through a village. Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

Aftermath of Battle

The Battle of Hill 70 served its purpose. It inflicted between 20,000 to 30,000 German casualties. The Canadians had depleted seven German divisions. As Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig recorded in his diary on 21 August: 'These two Canadian divisions have "knocked out" 7 German divisions viz.: the 7th, 220th, 4th Guard, 1st Guard Reserve (these are four of the very best divisions in the German army), 11th Reserve, 36th Reserve (these are not so good) and 8th Division (also very good). This fact is itself an indication of the enemy's moral[e]. That these two Canadian Divisions are now in such a fine state is due to having ample reserves to replace casualties, i.e. the result of sound organisation.'

The Canadian Corps earned itself an enhanced reputation in this battle, and was withdrawn from battle. The respite was short lived as the Canadians became involved in the last stages of the Third Battle of Ypres and the taking of the infamous village of Passchendaele.

Above: The 15th Battalion going out to rest after Hill 70, August 1917. Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

Further reading:

The Battle of Hill 70: Victoria Cross awards

Cyrus Peck, Piper Paul and the Canadian Scottish at Amiens

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association.

Appendix – Orders to the 5th Battalion, CEF.

Courtesy of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group