The Fijian Labour Corps

There are a number of less well known Corps which served in the war – but perhaps that of the Fijian Labour Corps is a particular rarity, given that just over one hundred men are listed on the medal roll for the Corps. Unfortunately no war diary survives for this unit in the National Archives collection, although diaries exist for the equally obscure Mauritius and Kurd Labour Corps.

Fiji, which lies a thousand miles North East of New Zealand, became a British Colony in 1874, and consists of over three hundred islands, a third of which are populated, and the largest can be identified on the following map from google.com. The main island, Viti Levu, is labelled ‘Fiji’ and contains the capital Suva. The second largest island, Vanua Levu, lies to the North East of Viti Levu, while Taveuni, the third largest island, and to the East of Vanua Levu, can be identified on the map by the village of Somosomo. Ovalau, the sixth largest island, and East of Viti Levu, is identifiable by the town of Levuka, the original capital of Fiji. Kadavu, the fourth largest island, lies to the South of Viti Levu, just off the map.

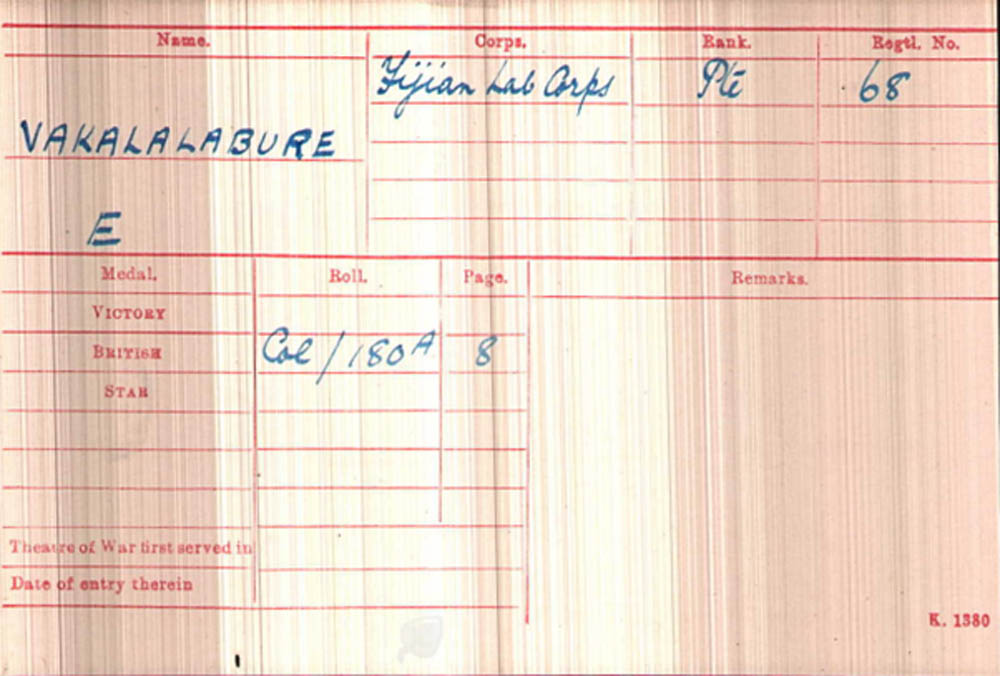

The existence of this Corps came to light through the recent pension card project carried out by The Western Front Association volunteers and was prompted by the Pension Card below.

The original research for this individual is shown, followed by a further study of the unit and the men who served therein, paying particular attention to those men who sadly didn’t make it back to their tropical island home.

His medal roll index entry confirms he served overseas and was awarded just the British War Medal (BWM).

The entry in the medal roll shows the return of the bronze BWM, and the subsequent award of a silver BWM and Victory Medal. This subject is covered later in more detail.

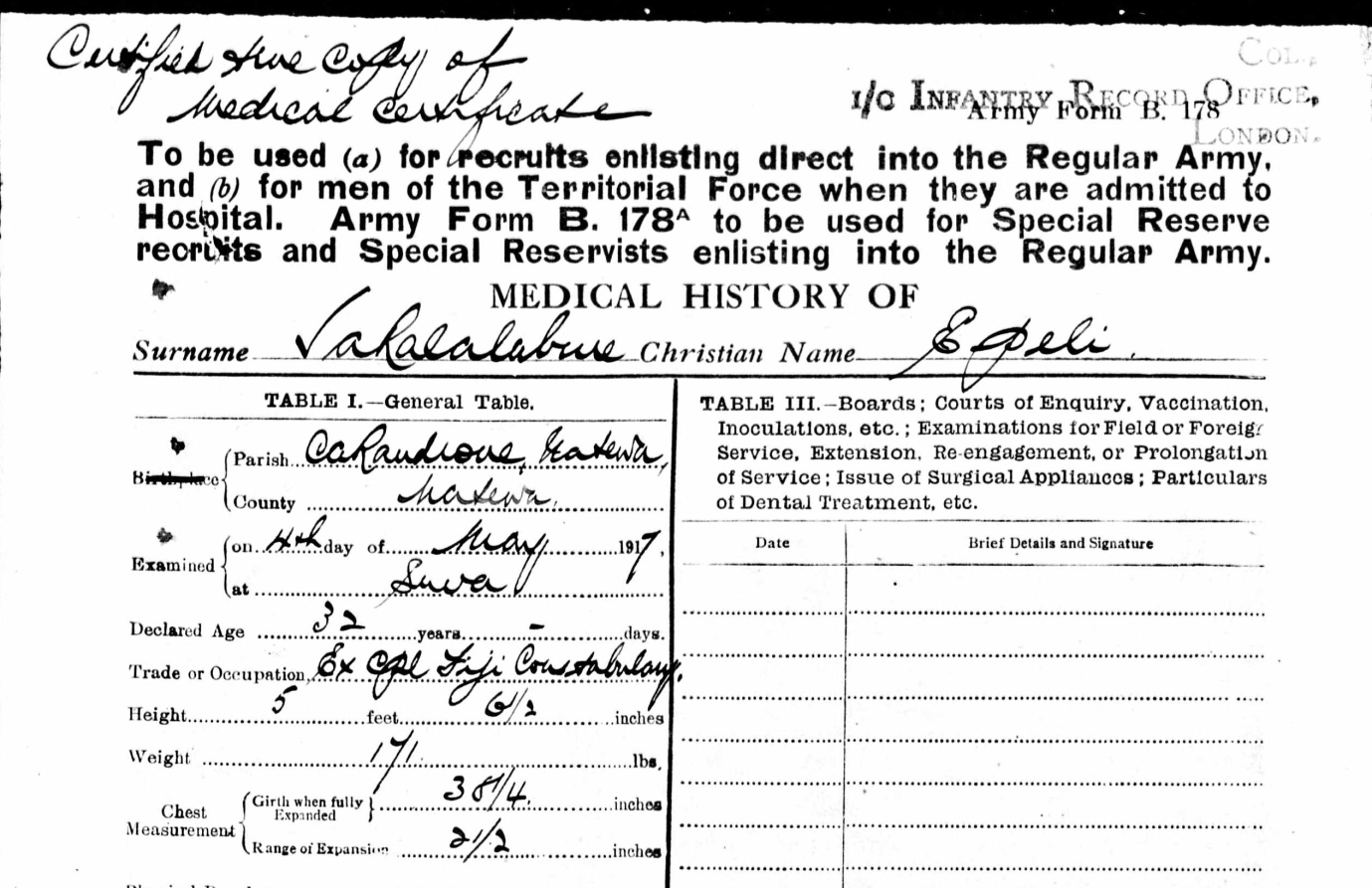

Surprisingly his service record has survived in the ‘Burnt’ series WO 363, although the usual attestation paper is absent. His christian name is recorded as Epeli, and a search of Fijian names almost certainly confirms that the name Elepi on the pension card is incorrect, so further references will be to Epeli Vakalalabure.

He joined the Fijian Labour Corps at Suva on 7 May 1917, aged 32, and his occupation on joining was described as an ex-corporal in the Fiji Constabulary, whereas postwar he was a civil servant.

He was from the village of Natewa, on the small peninsula to the East end of Vanua Levu, the second largest island of Fiji, in the County of Natewa, in the province of Cakaudrove, which itself embraces both the island of Vanua Levu, and also the smaller island of Taveuni.

Athough Viti Levu comprises several provinces, a number of smaller islands may be incorporated into a single province, which tends to make addresses far from straightforward, so It is not surprising that Epeli Vakalalabure’s correspondence address, contained elsewhere in the service record, is given as C/O the Secretary for Native Affairs, Suva, Fiji Islands, which would have proved a much more effective way of finding him.

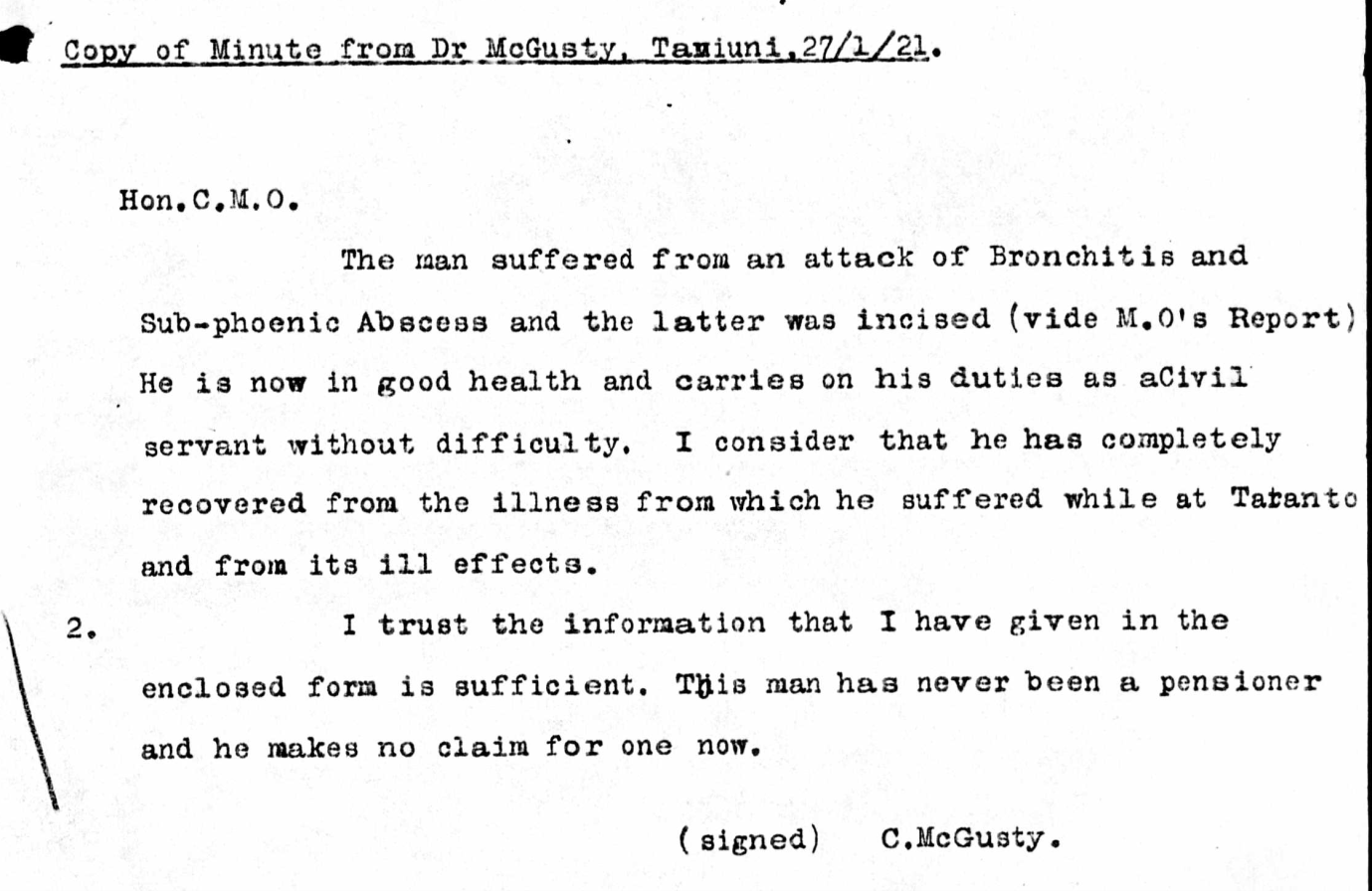

Epeli served in France from July 1917 to September 1918, before being transferred to Italy. He was discharged on 24 November 1919 being no longer fit for active duty, having been admitted to No 6 Labour Hospital in Taranto, Italy, in June 1919, suffering from bronchitis, and subsequently a sub-phrenic abscess, this being an accumulation of pus between the diaphragm and abdominal organs, and a serious condition which resulted in a disability assessed at the time as 100%.

It is quite evident from his records that he did actually receive a pension, but for just nine weeks, and which had been awarded pending the report from a medical board. This pension is recorded as being terminated on 17 May 1921, following receipt of the report from the said medical board, so presumably based on the above medical examination.

It hasn’t been possible to trace our man beyond 1923, when the pension card would appear to have been filed, Fijian records not being readily available for online access.

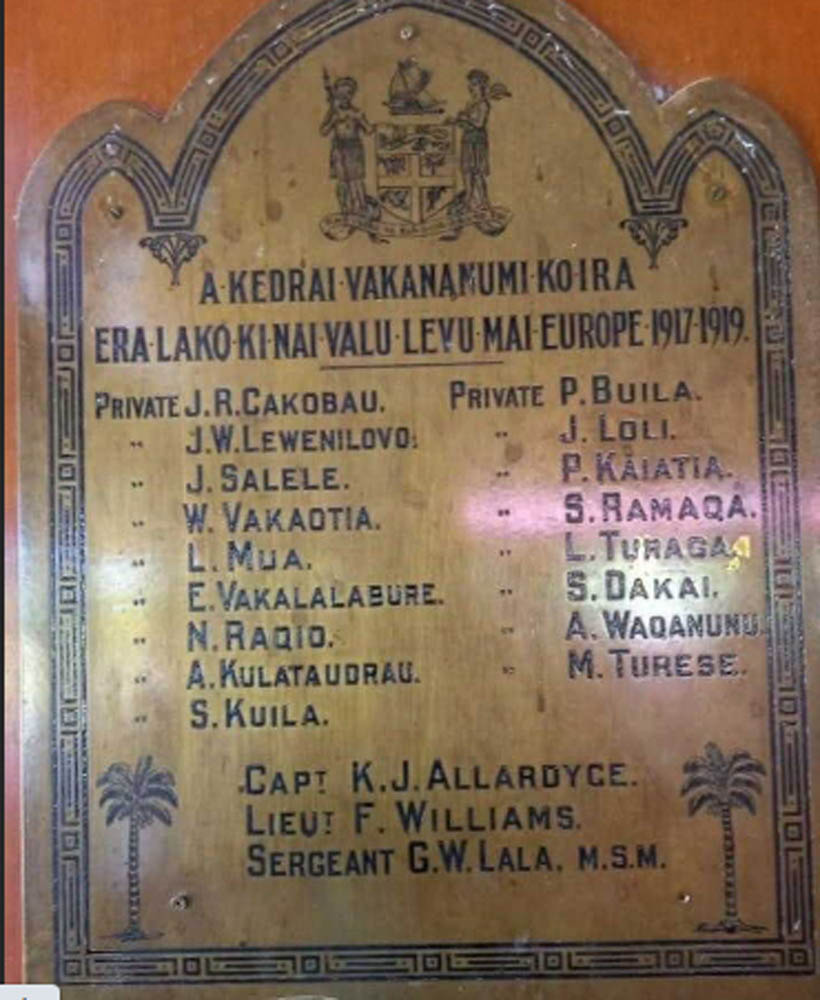

All the private soldiers on the memorial can be found on the Fijian Labour Corps medal roll, except for S. Kuila, who may have served under an alias. Wiliame Vakaotia’s service record has survived and he was from the village of Somosomo, on Taveuni, the third largest island of Fiji,and which is separated from Vanua Levu by a narrow strait. Since both Taveuni and Vanua Levu are in the province of Cakaudrove, perhaps this memorial, the exact location of which isn’t given, commemorates men from both islands.

The Fijian Labour Corps

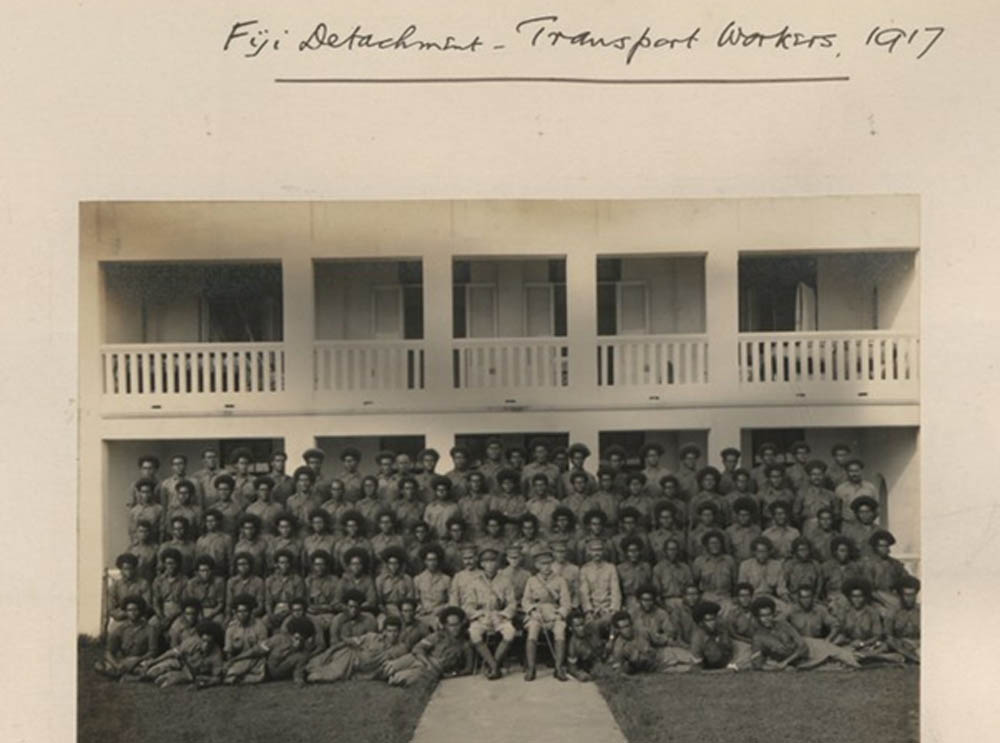

The Fijian Labour Corps was raised by the Governor of Fiji, largely from strong labourers, but also included several medical students, rejected by the RAMC, apparently because they were of the wrong colour.

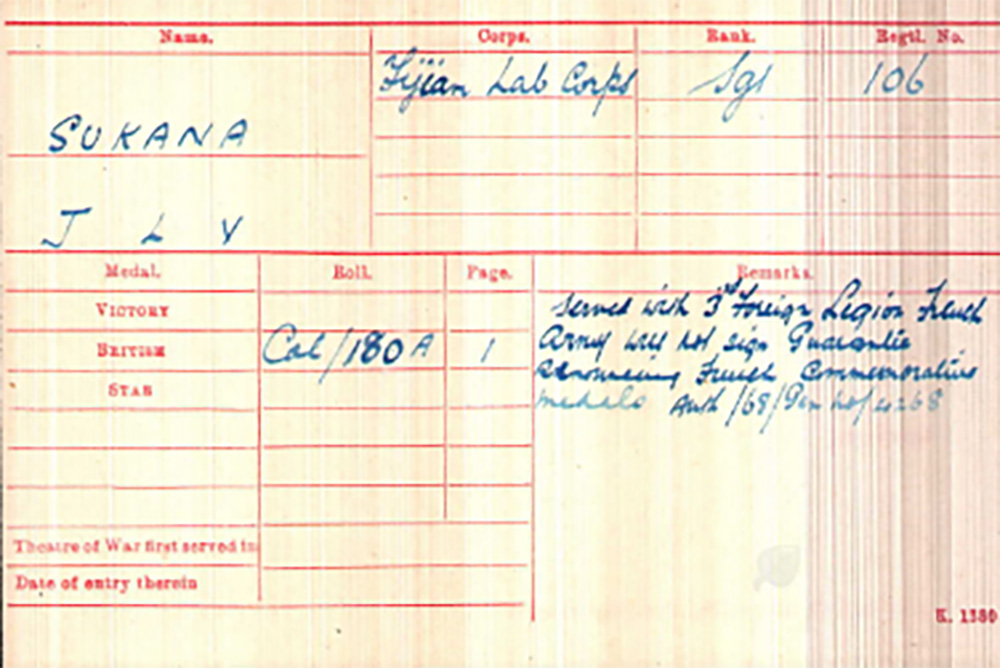

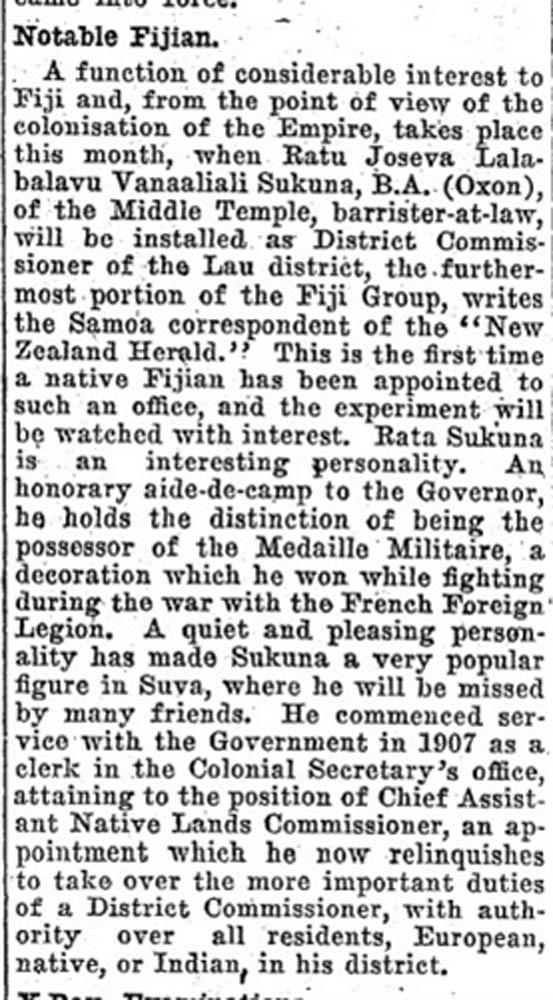

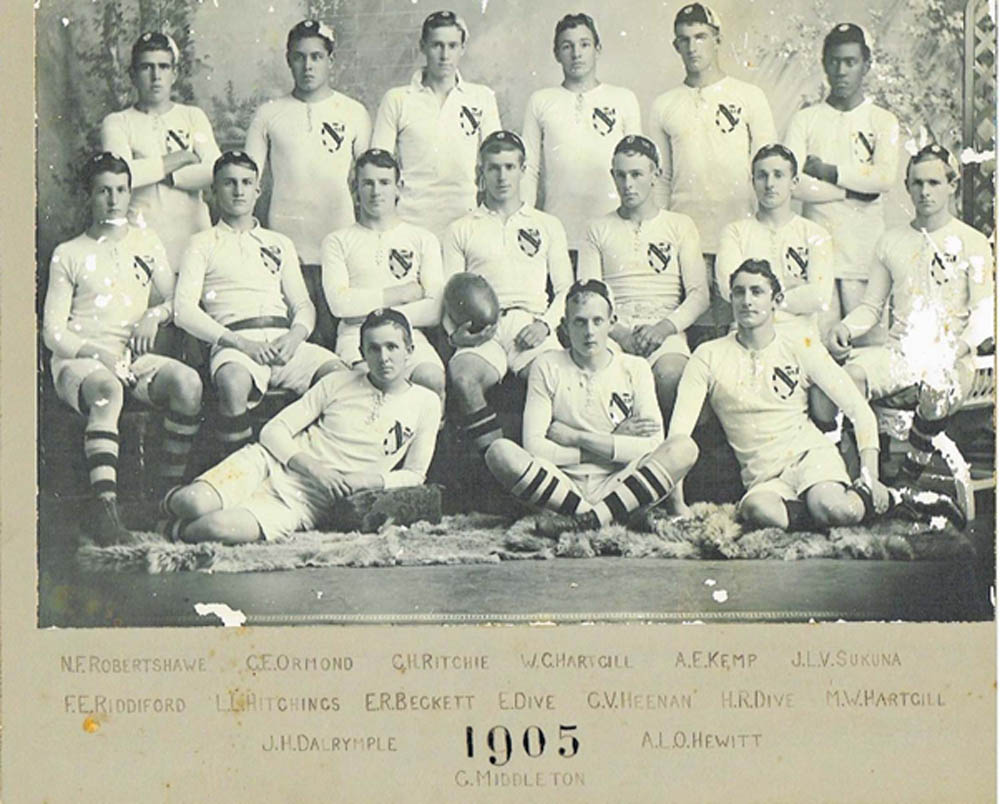

Joseva Lalabaluvu Vanaaliali Sukuna, a Fiji chief and an academic at Oxford University, had tried to join the British Army in England, in 1914, but after rejection, again very likely because of his race and colour, he joined the French Foreign Legion in early 1915. He fought on the Western Front, and was awarded the Medaille Militaire after being wounded in the second battle of Champagne in September 1915, before returning to Fiji, where he became instrumental in the formation of the Fijian Labour Corps.

It is often asserted that the unit was originally comprised of exactly 100 men, a fact borne out by the medal rolls, but that all officers and NCOs were British. The latter statement is in fact slightly incorrect, as the battle experienced Sukuna is listed on the medal roll as No.106, Sergt J L V Sukuna.

An article entitled ‘Marks’ Boys’ printed in the Fiji Times of 9 November 2014, some hundred years after the war started, provides much useful information, It states that with the indigenous population in decline, and with some succumbing to European illnesses, the British Government did not want to be held responsible for heading the Fiji race towards extinction, so despite a willingness to fight, it was considered necessary to keep the men away from the front lines.

In order to maintain discipline, Sukuna insisted that chiefs were among the men, and at least five senior chiefs were in the contingent. A prominent business man, Henry Marks, had provided £10,000 to fund equipment, transport and separation allowances for dependants, which led to the unit, commanded throughout by officer Kenneth James Allardyce, becoming known locally as Marks’ Boys.

The articles goes on to state that the men were noted as muscular and fit, the largest man being 6 ft 3in, not including several inches of hair, and weighing 216 pounds, with all flesh being trained muscle.

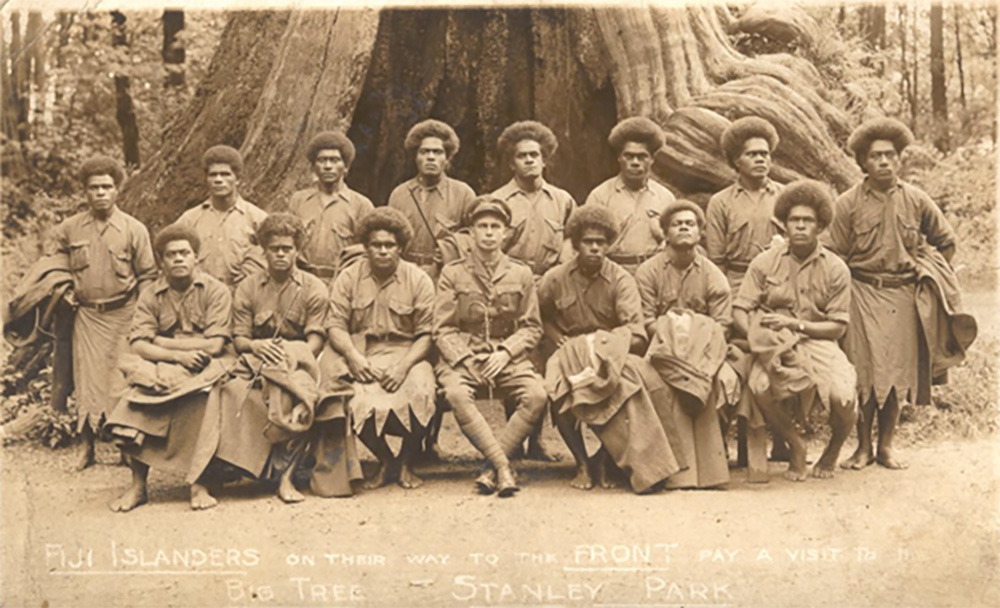

A post by Christine Liava’a on facebook is very helpful in tracking the Fijian Labour Corps. They left Fiji on 19 May 1917 and reached Vancouver, Canada by way of Honolulu, Hawaii and were pictured with their officer in Stanley Park, Vancouver, in bare feet, wearing sulus (wraparound skirts) and great coats. Christine published her comprehensive book ‘Quaravi Na’i Tavi: They did their Duty: Soldiers from Fiji in the Great War’, back in 2009.

They then travelled across Canada by train and sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Liverpool, before arriving at Calais on 4 June 1917. The men were largely involved with work in the docks, handling war related cargo, and had a reputation as excellent stevedores, being both strong and hard working. Although they were apparently banned by the French from using cafes, they had an excellent reputation with both French, British and Commonwealth troops.

A letter home from Ratu Glanville stated ‘Our stay in Calais was a pretty warm reception. We had air raids every night and morning. When the first raid greeted us, it was a fine sight to see the aeroplanes up in the air and the shells bursting all around them. But when Jerry began dropping his bombs I had the ‘wind up’ right enough’. This extract from the Fiji Times article of 9 November 2014 is from a letter, originally published in the same paper, of 29 July 1919. Note this man would be Ratu Glanville Lalabalau, listed among the chiefs in the article, and who evidently ended the war as Cpl. G.W. Lala.

The Corps was transferred to Marseilles on January 24 1918, and again the same Fiji Times article of 2014 records that in a letter home of 11 March 1918, and originally published in the Fiji Times of 27 May 1918, Malakai Vunidovu (Pte 49 M. Vuniduvu in the Medal Roll) wrote a letter home, noting the eagerness of the men to see real action, saying ‘At present we are all exceedingly anxious to be sent to the trenches’.

They officially became the Fiji Labour Corps, by Royal Warrant, on 1 July 1918. A party of fifteen were sent to London in August 1918 to meet the King. This included Ratu Glanville, quoted as saying the people in London were very kind to the men of the Labour Corps.

Probably because of their susceptibility to pneumonia and other diseases (see later) they were sent to Taranto, Italy in 1918, in search of a better climate. Taranto was an important Mediterranean port linking supply routes between Egypt, Palestine, Mesopotamia and Salonika.

The Fijian Labour Corps would have been stationed at Taranto during the time of the infamous mutiny, caused largely by the racial treatment, bigotry and disrespect directed at the men of the West Indies Regiment while they were awaiting demobilisation.

The Fijian Labour Corps returned home on the ‘Kia Ora’ in October 1919, via Virginia, and the Panama Canal.

Available Records

Note this section is mostly based on original research by the author.

Medal Rolls & Index Cards

An attempt to correlate the various records relating to men of the Fijian Labour Corps was beset by problems, partly relating to the various spellings of the names of the men. The only complete list of men was found in the medal roll, hidden away on Ancestry.com under the obscure, and incorrect, title of ‘Native Interpreters, Machine gun porters’.

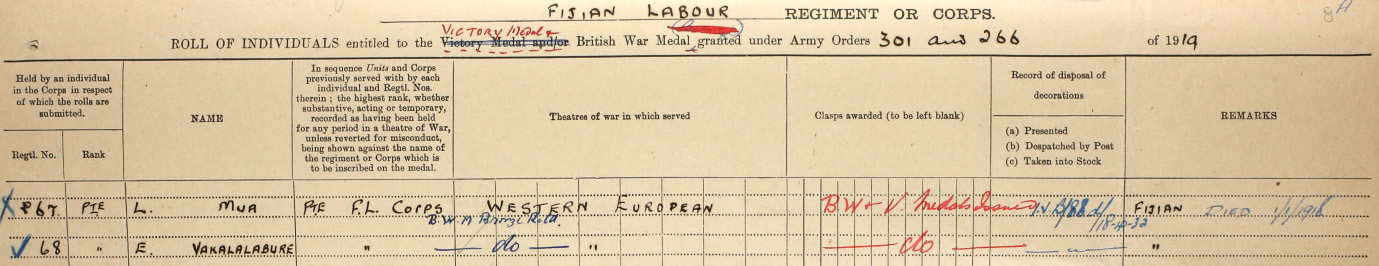

The medal roll is quite specific in stating that awards were made to 105 men. Those men listed with service nos 1-100 were all privates, except for no 69 G.W. Lala and no 72 I.N. Tawake, who were corporals by the end of the war. There were 5 sergeants holding nos 102-106, but It is unclear why no 101 appears not to have been included in the medal roll, particularly as the Fiji Times article on ‘Marks’ Boys’ specifically states there were six sergeants in the group. One possible reason is that no 101 was indeed allocated to the sixth sergeant, but that he did not actually serve overseas with the rest of the contingent.

The medal roll indicates that the British War Medal (BWM) and Victory Medal (VM) were initially awarded to NCOs only, this is confirmed by individual medal index cards. The exception was Sgt 106 J.L.V. Sukuna, who evidently refused to renounce his entitlement to his French medals awarded for service with the French Foreign Legion, and was initially issued with just the BWM.

The 100 other men, were all originally awarded the BWM in bronze, and no Victory Medal, in line for example with the Chinese, Maltese, and South African Labour Corps; again this is confirmed by the individual medal index cards. However the roll indicates that the BWMs were in fact returned, and exchanged for a silver BWM, plus a Victory Medal, although this is not reflected in the medal index cards. Eleven bronze BWMs were reported as lost, but in each case the man received his new pair of medals, however in the case of Pte 84 S. Vulawalu, the bronze BWM was indicated as ‘not recovered’ and there is no recorded reissue of the correct medals.

There has been much discussion as to whether the issue of the BWM in bronze was a cost saving measure, or whether it was to discourage the recipient from melting it down. Ironically bronze BWMs now carry a large premium amongst collectors because of their relative scarcity, and a surviving example to the Fijian Labour Corps would be incredibly rare. Perhaps in this case the Fijian hierarchy successfully objected to the clear discrimination and it was rectified.

It is of course impossible to know from the medal roll if the spelling of names is correct, and anomalies were found when checking these names against both surviving service records and available pension cards.

Christian name variation had been previously encountered for Pte 68 Vakalabure, in the initial study, and an example of surname variations involves Pte 74, he being variously referred to as K. Naqesa, Kaloboso Naquesa,and Kaloboso Nagesa in different records. For clarity, the surname spellings used in this study adhere to those found in the medal roll. Christian names have been gathered, wherever possible, from CWGC records, service records and pension cards.

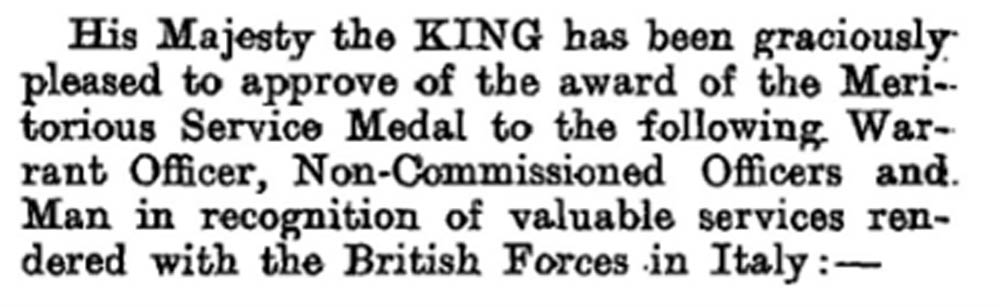

Meritorious Service Medal and MBE

The MSM was awarded to Cpl (A/Sjt) 69 G.W. Lala (believed actual name to be Chief Glanville Lalabalau, who was one of the party to have met the King), and also to Pte (A/Sjt) 50 J Colata, both for service in Italy.

The same edition noted that their commander was appointed a Member of the Military Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, (MBE) for distinguished service in connection with Military Operations in Italy.

Service Records

A small number of service records have survived in the burnt series, WO 363, but rather unusually these are more akin to those normally found in series WO 364, always lacking the usual form of attestation papers, and instead commencing with army form W 3997, ‘Cover for Discharge Documents’. Fortunately all these records contained an Army Form B. 178, ‘Medical History’, which gives details such as age, height and weight, plus address and trade. An example for Pte 68 Epeli Vakalalbure was shown earlier.

Only five such service records could be found, and just six pension cards. There is a very strong correlation between these two types of record, with pension cards being found for four of the five men with service records, and all men with service records shown to have suffered either death or disability. The service record of the one man without a pension card noted that although he had been incapacitated, his wounds were now healed.

Pension Cards

The pension cards were comprehensively searched using the surnames from the medal roll, and also any variants found in service records. Most of these surnames proved to be unique, and evidently confined to Fiji.

The cards were originally indexed under the various interpretation of the unit name found on them, consisting variously of Fiji Lab C, Fijian Lab Cps, Fijian Lab Corps, Lab Corps (Fijian) and Labour Corps. As a result of this study the index entries have been modified so that all cards can now be found under ‘Fijian Labour Corps’.

Casualties

The memorial to the casualties of the Fijian Labour Corps, is at Levuka, the original capital of Fiji, and situated on the coast of Ovalau, Fiji’s sixth largest island.

CWGC records twelve deaths for members of the unit, a very high rate of attrition for a non combatant-corps numbering just a hundred men. Unsurprisingly, most of the casualties are buried in cemeteries associated with the ports they served at, with one in Calais, five in Marseilles and three in Taranto.

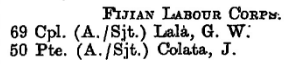

The first casualty was Pte 67 Lekima Mua, who died on New Year’s Day 1918 and is buried in Les Baraques Military Cemetery, Sangatt, West Calais. CWGC records he was the son of Ratu Sakiusa Vakolo, of Somosomo, Taveuni. The title ‘Ratu’ indicating his father held chief status.

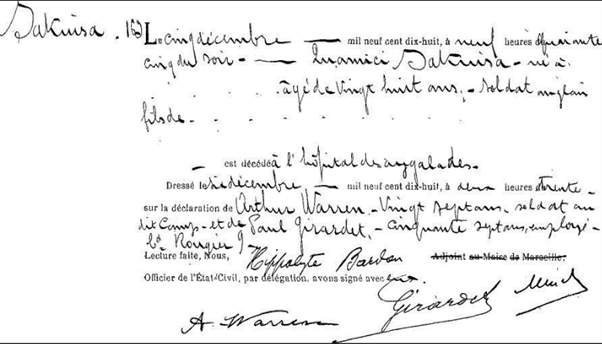

Lekima died at ten o’clock in the morning of 1 January 1918 in No 30 General Hospital Calais, and is recorded as being of unknown age, and worker no 67 in the Fijian Labour Corps of the British Army. He is listed as a resident of ‘Somo, Somo, “Taveune” (Iles Fiji)’, clearly referring to the village of Somosomo, on the Fijian island of Taveuni.

A minor error in the CWGC records has resulted in Lekima being recorded as serving in ‘67th Coy.’ of the Fijian Labour Corps, obviously confusing his service number with a non-existent company in this small unit.

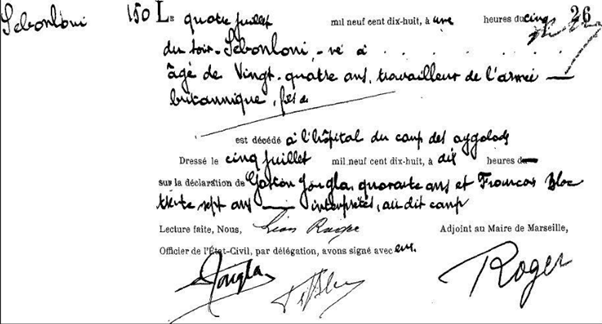

The men who died while the Corps was at Marseilles are either buried or commemorated at Mazargues War Cemetery, Marseilles.

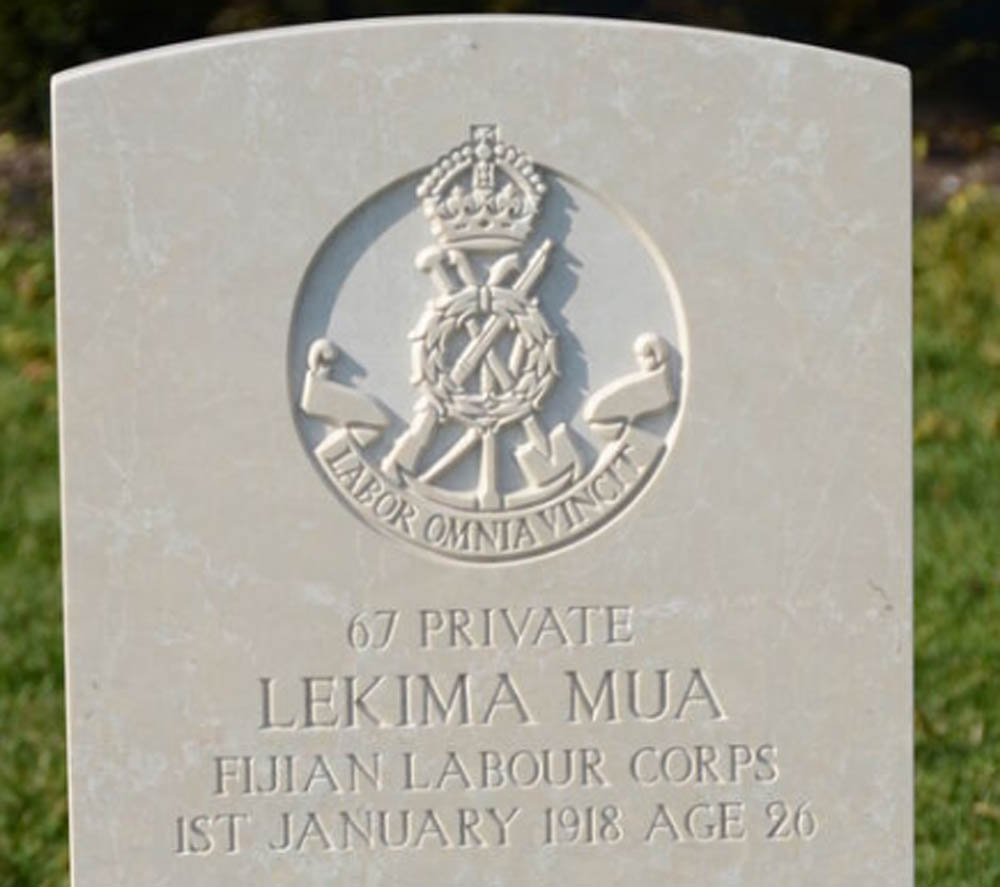

The first man to die in Marseilles was Pte 41 K. Raiciuciu, on February 1918, and he was buried in Mazargues War Cemetery. (Note one grave registration document misspells his name as Raicincin, although the CWGC headstone document records his name as Raiciuciu. This name is in line with the medal roll, and the juxtaposition of ‘u’ and ‘n’ seems to be is the most common anomaly in the records.)

The record notes his age as twenty two, and shows he died in the English hospital at Musso Camp, on 16 February 1918 at four o’clock in the morning. This hospital was most likely No 16 Convalescent Depot, established at Musso Camp in January 1918 utilising huts previously home to the West Indies Regiment, and about seven miles from Marseilles.

According to CWGC records, Pte 40 Maciu Natogo, and Pte 11 Avenisa Kalavo died on consecutive days in June 1918.

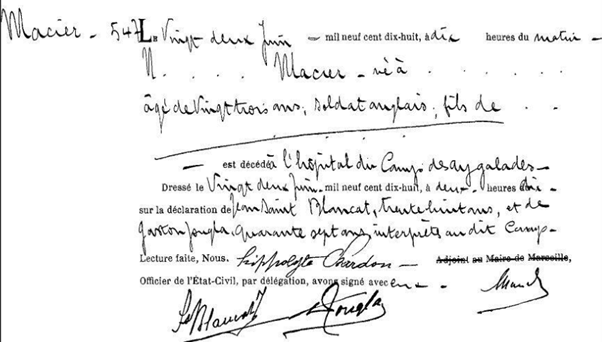

He died at 10 o’clock in the morning of 22 June 1918, at l’hopital du Camp des Aygalades, located in the Les Aygalades area of Northern Marseilles, and is recorded as a twenty three year old English soldier. His death has been indexed in the French records as ‘Macier N’, but close inspection of the document reveals ‘Macieu’, his christian name, rather than Macier, so his death has been recorded under his christian name, and just the initial of his surname.

He died in the same hospital as his comrade, Maciu Natogo, and is recorded as a twenty three year old English soldier. He died at 1 o’clock in the afternoon, on 24 June 1918, rather than on 23 June, as recorded by CWGC.

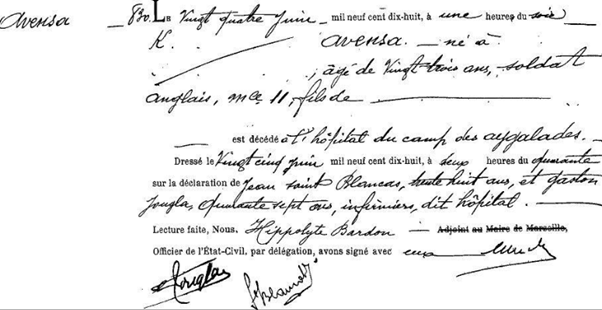

Pte 34 Sebonloni Tavaga died shortly afterwards in July 1918.

He died at five o’clock in the evening of 4 July 1918, and was recorded as a twenty four year old worker of the British army. It is fortunate that his full name is recorded in the CWGC grave registration records, as his name is simply given as Sebonloni, his christian name.

Ptes Natogo and Kalavo and Tavaga were all originally buried in St. Pierre Cemetery, Marseilles, this was one of several cemeteries concentrated after the war into Mazargues cemtery, and presumably the closest to the hospital where they died.

The last man to be buried in Mazargues is also subject to some confusion. The medal roll identifies this man as Pte 57 S. Qaniuci, and actually states therein that he died on 5 December 1918.

One CWGC burial register, lists him as Pte 87 S. Qaniuci, suggesting they got the number wrong. To add confusion, a second graves registration document lists him as Pte 87 Q. Sakinsa, Fijian Lab. Coy., who died 5 December 1918, thus replicating the numerical error and seemingly introducing a totally spurious name.

The record of his death goes some way into resolving the circumstances leading to confusion.

Where the CWGC grave registration gave his name as Sakinsa, this may well be their interpretation of the above death record, which has been more recently indexed by the French authorities as Sakuisa. The important fact is that his name is listed in the above archive record as Quarnici Sakuisa, so surely this man is Pte 57 S. Qanici as seen in the medal roll of the Fijian Labour Corps. His first name would have actually been Sakiusa, an exceedingly rare christian name, except that is in Fiji.

This has to be a classic case of the various possible interpretations of a written record as to exactly where the ‘i’ has actually been dotted, and also another example of the transposition of christian and surnames.

He was descibed in the above record as being a twenty eight year old English soldier, who died around five o’clock in the evening of 5 December 1918, at l’hopital de aygalades.

Fortunately the headstone document on the CWGC website confirms he has the correct number and name on his headstone, being Pte 57 S. Qaniuci, Fijian Labour Corps.

The next death was that of Pte 58, Abraham Vonoyauyau Evaranu, who was born in Nakelo, Tailevu Province, Viti Levu. He died on 16 February 1919, and was buried at Auckland, New Zealand, presumably having been invalided home, but sadly not making it all the way back to Filji. The CWGC Grave Registration document states that he has a ‘stone erected privately’ as a memorial.

Despite the move to the warmer climate of Southern Italy, Pte 5 A. Boa died on 9 May 1919, and was the first of three men to be buried in Taranto Town Cemetery Extension.

Pte 45 V. Nailotei died exactly a week later, and Pte 39 R. Williams died on 19 July 1919, the last two men to end their lives in Europe.

Sadly Pte 91 Wiliame Vakiotia died at sea on the journey home with the rest of the Corps, and is commemorated in the United Kingdom Book of Remembrance. Wiliame is one of just two casualties to have a surviving service record, from which the following information was extracted.

Wiliame Vakaotia, was from the village of Somosomo, on the island of Taveuni, a part of Cakaudrove Province, and the fifth largest island. His occupation was given as Turaga ni Koro, Somosomo, indicating that he was the village chief. He suffered from tubercular disease of the sacrum, which is a rare form of spinal tuberculosis, and also from pulmonary TB, and additionally from scoliosis of the sacrum, which would have led to spinal curvature. He was clearly a very sick man, which would perhaps account for his death at sea, when his pension was duly cancelled. He was evidently from the same village as Pte 57 Lekima Mua, buried at Calais in 1918.

Note: Wiliame’s occupation was only interpreted by finding an online article from the Fiji Times of 12 April 2017, and noting that the current holder of the post of ‘Turaga ni Koro’ was described therein as ‘Headman of the village of Somosomo’ and had apparently refused to accept dismissal by the Fiji Government. Wiliame was evidently one of Sukuna’s ‘chosen men’, a chief selected for help with discipline.

The twelth and final casualty was Pte 13 Venisoni Vitilevu, and he is the only other casualty to have a surviving service record, and which records the following details.

He was descibed as a farmer from Ra Halaba, Burelevu, which refers to Burelevu village in the Ra province to the North East of Fiji’s largest island, Viti Levu. He contracted tubercular peritonitis and pulmonary TB while in service, and died on 27 December 1919, after his return to Fiji. He is buried at Suva Old Cemetery , one of only four Commonwealth burials from the Great War. His pension was to be paid only up to the week of his death..

Pension records could not be found for any of the other ten men who died.

Apart from Pte 68 Epeli Vakalalabure, covered earlier in this article, there were two more survivors of the war who have service records in series WO 363.

Pte 74, Kalaboso Naqesa, a clerk from Nailaga, (on the North West coast near Ba Town), Ba Province,Viti Levu, suffered from pneumonia, bronchitis, influenza and pulmonary TB, all associated with war service.

Pte 6, Wilkinisoni Dvilomaloma, was a marine fireman and wharf labourer from the island of Kadavu. He suffered tubercular ulcerations of his left hand index finger, hand and arm, but these healed, with no evidence of T.B. elsewhere, and although the disease was originally considered liable to break out again, he was assessed in late 1920 to have no lasting disability, and is the only man with a service record but no pension card.

Two further survivors of the war have a pension card, but have no locatable service record. These are Pte 21 W. Misivsa and Pte 75 Eparama Vakacabeqoli, the latter’s full name being obtained from his card. Both men must have suffered a significant degree of incapacity.

It is a reasonable assumption that many of the other men suffered similar illness, and that most of the deaths had similar causes, being related to T.B. These men were particular susceptible to respiratory infections, lacking immunity from disease, something they themselves would very likely have been unaware of when they enlisted.

The intention by the British Government had been to protect the men from front line duties, but the threat from European disease was clearly underestimated. This was despite the Fiji population having been ravaged by a measles epidemic in 1875, just one year after becoming a British Crown Colony, and which accounted for at least 25% of the population.

Another serious measles outbreak took place in 1911, on the smaller island of Rotuma, which had escaped the 1875 outbreak, but now lost over 10% of its population. With multiple islands, complete immunity to a specific disease across the whole population was difficult to achieve, and susceptibility unpredictable.

A Notable Fijian

Although a collection of Fijian vital records from 1871-1990 is available on Familysearch.com, it is difficult to trace the civilian life of most of the men who served in the Corps with any certainty, with the exception of the founder.

Sergeant 106 J.L.V. Sukuna, the man behind the unit’s formation, became very highly regarded as the founder of modern day Fiji, transforming it from a colonial outpost to an independent nation, and is variously known as Ratu (chief) Sukuna, and Sir Lala Sukuna. The last Monday in May is a public holiday, known as Ratu SukunaDay, and devoted to his memory.

Following retirement he sadly died on board the SS Arcadia on 30 May 1958, his name being crossed out from the passenger manifesto on the ship’s arrival in London on 17 June.

Fiji gained independence on 10 October 1970, after 96 years as a British colony, taking over from previous guidance on governance, law and education.

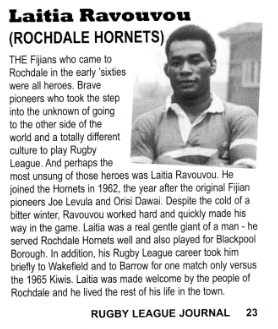

Fijians in Rugby League

As an aside, a small number of Fijians played for Rochdale Hornets Rugby League team in the early 1960’s, and were held in very high regard. A certain Laitia Ravouvou, a 6ft 3in second row forward, reputedly holds the unlikely record of being the only man ever to kick a goal in professional rugby while in bare feet, although the cold winter of 1962/3 did make the men wear boots.

This bold move, to play an unfamiliar game in a far off country, shows the same spirit in which men from Fiji had volunteered to serve in Europe, as well as illustrating their physical size, popularity, and amiable demeanour.

The legendary J.L.V. Sukuna would doubtless have approved of this venture. The game of rugby union, pre-dating rugby league, had been introduced to Fiji by the British, as early as 1884, and needless to say he was a good player, regarded as a more than competent wing forward during his education spell in New Zealand.

Summary

This was truly a race of strong, brave and well disciplined men, equally adept as dockyard labours under bombardment in wartime, and also in the toughest of sports. The men of the Fijian Labour Corps would undoubtedly have made a formidable fighting unit, given the chance.

Acknowledgements

There are many well informed discussion items on greatwarforum.org, mainly from some twenty years ago, which proved indispensible to the author’s understanding, and which provided the basis for further research. Of particular note were those posted by Ivor Lee and by the author Christine Liavai’a. Excellent photographs of four CWGC headstones in Marseilles have been posted in more recent years by member Trek and can be found on the same website.

Note that high quality images of the photographs found in the album on flickr.com are available on request from the National Archives.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

Identify key words or phrases within back issues of our magazines, including Stand To!, Bulletin, Gun Fire, Fire Step and lots of others.

The WFA's YouTube channel features hundreds of videos of lectures given by experts on particular aspects of WW1.

Read post-WW1 era magazines, such as 'Twenty Years After', 'WW1 A Pictured History' and 'I Was There!' plus others.

Other Articles

From Putney Bridge to Jallianwala Bagh: The 1/25th County of London Cyclists 1914-1919

Read more

More than just Gallipoli: Naval operations in the Eastern Mediterranean 1914-16

Read more