The Generals. John Terraine's 1982 Address to The Western Front Association

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Generals. John Terraine's 1982 Address to The Western Front Association

[This piece, a transcript of John Terraine's 1982 address, first appeared in Stand To! No. 7 Spring 1983 pp.4- 7]

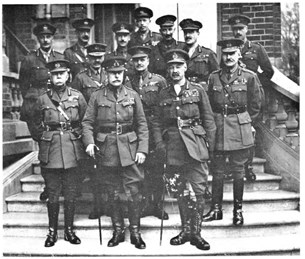

IMAGE (Photo: IWM Q9689)

Haig and his Army Commanders at Cambrai, 11 November 1918. First and second rows, left to right: Plumer (Second Army), Byng (Third Army), Haig, Birdwood (Fifth Army), Rawlinson (Fourth Army), Horne (First Army). (Photo: IWM Q9689)

What I propose to talk to you about today - I hope you will approve - is The Generals - by which I mean the generals of the Western Front, and particularly our own, the British generals. I don't suppose any group of military men in history has ever had such a persistently "bad press", such an unending stream of criticism as those unfortunate officers who led the British Army to the greatest sequence of victories in its history.

I find it very strange.

And it began, of course, very early. I said to you last year that if 1918 was the year of the British Army's glory, 1915 was the year of its tragedy. It was the year when people began to get an idea of what they were up against; what kind of an enemy we had taken on; what it might cost to beat him. It was a year of shameful shortages - shameful for a great industrial nation: a shortage of weapons, a shortage of munitions of war of all kinds, a terrible shortage of trained soldiers, which meant that scarcely-trained men, devoid of military experience, were flung into battle against the most powerful army in the world.

There were - not surprisingly - some ugly scenes: the Second Battle of Ypres - a very grim experience indeed; the fiasco at Aubers Ridge; Festubert, which was hardly any less of a fiasco; Loos, which in some respects was not far short of a disaster. And also not surprisingly, when they became aware of these matters, people started looking around for someone to blame. The generals, of course, were very conveniently placed for that.

By the end of 1915 there was very considerable discontent with the way the war was being conducted. Gallipoli was an obvious failure; the Western Front seemed to be not only a failure, but a hideously costly one. Once more it is no surprise to find that some of the sharpest criticism came from voices overseas - the great British overseas Dominions were populated by people who prided themselves on their outspokenness, the absolute candour with which they were prepared to tell the people of the Old Country exactly where they were wrong.

William Oliver, a Scotsman who had emigrated to become a barrister in British Columbia, wrote to his brother F.S. Oliver in London, in November 1915. Canada, he said, was very loyal; there was no repining at having joined Britain in the war; but he added,

"there is a feeling growing very strongly everywhere that the British generals one and all are the most incompetent lot of bloody fools that have ever been collected together for the purpose of sacrificing armies in historic times." (1)

"Sacrificing armies": it is an interesting phrase. It is a very Anglo-Saxon phrase -Americans use it too, but never to the extent that we do. You can catch the echoes of it every day, on the Sports pages of our newspapers. A setback in the World Cup competition, for example, is far more likely to be described in terms of poor play by our side than good play by the others. In a Test Match, the headlines will say: ENGLAND batting collapses. I have yet to see brilliant Australian bowling heading the story!

And so it was with the war. Our armies were being "sacrificed"; there was, apparently, no other conceivable reason why they should sustain heavy losses in battle against the most powerful, best equipped, best trained army in the world.

I often think, you know, that many of those who concern themselves with British casualties in the First World War, and squarely blame them on our generals, are rather like a detective, investigating a murder, who suspects everyone except the man found standing over the bullet-riddled corpse with a smoking revolver in his hand. I am a great believer in simplicity in war studiesand it is a simple fact that the overwhelming majority of British casualties in World War I were caused by German weapons wielded by the German Army, an institution very well able to do precisely that. So I blame the Germans.

However, a national characteristic is a national characteristic; it can defy logic.

And it has to be admitted that the mounting toll of the war, and its increasing cruelties, defied logic, and understanding too.

The Battle of the Somme, in 1916, was a dreadful eye-opener to the realities of modern war. The Battle of Arras, in 1917, was another; even that normally dispassionate work, the Official History, says that the later stages of the fighting round Bullecourt had "the most ghastly accompaniments". It quotes one of those who took part, describing the nauseating stench of the unburied dead all over the battlefield, and saying he was astonished "that any human beings could hold and fight under these conditions." (2) It was worse in this respect, he said, even that "Third Ypres".

And this was the battle which prompted Siegfried Sassoon's bitter little poem, The General:

"Good-morning; good-morning!' the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the Line,

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of 'em dead,

And we're cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

'He's a cheery old card', grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

Sassoon's poem appeared in 1917, (3) and I think I am right in saying that virtually all his war poems appeared while the war was still on, as did Wilfred Owen's and other war - or should I say "anti-war" - poetry.

After the war came the memoirs and the novels and the critical histories. We had the literature of "Disenchantment" - a great flood of it-in the Twenties and Thirties. For the generals, this was the "bad press" - at any rate, this was when it began to be significant.

Lloyd George, wartime Prime Minister, had been nursing a mounting loathing and contempt for the British generals while the war was on. Angry and frustrated at his own fall from power, and fearing that he was being blamed for the miseries of the war, he used his Memoirs to shift the blame from politicians to soldiers, from himself to FieldMarshal Lord Haig and Field-Marshal Sir William Robertson. He did it very effectively, to the tune of over 2,000 closely printed pages. (4)

Critics like B.H. Liddell Hart and MajorGeneral J.F.C. Fuller chimed in. Novelists made their contribution; C.S. Forester's brilliant, but cruel novel, The General, came out in 1936. By the outbreak of World War II the "bad press" of the British generals was copious indeed - and it did not make life any easier for their successors grappling with the problems of the Second War.

And the Second War made matters worse.

Because Britain's casualties were only about half as many (in a longer time) as in World War I, it was easy for people to jump to what seemed an obvious conclusion - that the Second War was much better managed than the First, and the new generation of generals much better than the one before.

It was nonsense, of course, as I shall hope shortly to show. But it helped to produce a new wave of World War I literature, a new onslaught on the British generals, in books like Leon Wolff's In Flanders Fields in 1959, Alan Clark's The Donkeys in 1961, and many more.

And it continues to this day.

In April of this year the magazine War Monthly contained a savage attack on Lord Haig, blaming him for "a blood bath in which the cream of British manhood was destroyed" thus causing "the decline of Britain in the years ahead from a first-class to a third-rate power." And only about three years ago John Keegan, who can sometimes write about war very well indeed, reviewing my book To Win a War, (5) in which I had the temerity to suggest that the British Army, from the youngest conscript to the Commander-in-Chief, did rather well in 1918, refered to

"that hideously unattractive group, the British generals of the first world war, whose diaries reveal hearts as flintlike as the texture of their faces."

That was in The New Statesman; no risk of disturbing the prejudices of its readers! I am not saying, of course, that these are the only voices that have been heard on the subject of our generals. The contrary - or at the least, a much more moderate - view has also been expressed. The Official History permits itself to be critical at times - but it is always a balanced criticism. Winston Churchill, though opposed to much of the strategy of the war, was never vituperative like Lloyd George. The sarcasms of Liddell Hart were offset by the level-headedness of that excellent war historian, Captain Cyril Falls. Sir Edwards Spears and Charles Carrington made the voice of reason heard in all they wrote. The generals have had their defenders - and quite right too! But the strength and persistence of the attack is a remarkable phenomenon.

I think the only way to straighten this subject out is to go right back to basics.

We have to ask ourselves, "What is a general for?" What is his job? And I cannot think of a better answer to that question than the one supplied by the man who was both one of the most successful and the best-loved of our generals in World War II - Field-Marshal "Bill" Slim.

In his superb book, Defeat into Victory, (6) writing about that ghastly retreat through Burma back into India in 1942, Slim wrote:

"Defeat is bitter. Bitter to the common soldier, but trebly bitter to his general. The soldier may comfort himself with the thought that, whatever the result, he has done his duty faithfully and steadfastly, but the commander has failed in his duty if he has not won victory - for that is his duty. He has no other comparable to it."

And that seems to me to be absolutely true. As I said in my book, the Smoke and the Fire, (7) "it is his estimated capacity to obtain victory that entitles a general to his badges of rank, his quarters, his ADCs, the salutes of the Quarter-Guard, and the salary he receives.”

Field-Marshal Sir John French: C-in-C BEF, 5 August 1914-19 December 1915. (Photo: P.T. Scott)

Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig: C-in-C BEF, 19 December - 1 April 1919. (Photo: P.T. Scott)

General Sir William Robertson and Marshal Foch at Cologne in 1919 (IWM Q7629)

Victory is what he is for.

In no other war that I can call to mind in all history has it been put about that a general's chief duty is to avoid casualties. No one questions the Duke of Marlborough's claim to be considered a "great captain" - despite the fearful losses of Malplaquet. The Duke of Wellington, in Spain and at Waterloo, presided over scenes of awful carnage - bad enough at Waterloo to bring tears to his eyes. Many of Napoleon's battles were sheer blood-baths. General Robert E. Lee, often considered an outstanding military genius, never hesitated to accept heavy casualties in the pursuit of victory. The Soviet marshals of World War II were undismayed by the veritable massacre of their men in the same quest - but nobody hounds their memories as the British generals of the World War I have been hounded.

How do those British generals stand up to Slim's test? If, as he says, victory was their chief and over-riding duty, it is a simple historical fact that, whatever their faults may have been, they did not fail in their duty.

It was not a British delegation that crossed the lines with a white flag in November 1918.

No German Army of Occupation was stationed on the Thames, the Humber, or the Tees.

No British Government was forced to sign a humiliating peace treaty.

The British generals had done their duty: their army - and their country - were on the winning side.

And that, as I see it, is the only proper, the only sensible starting point for estimating their quality. When we talk about the British generals, we are not talking about men who failed, we are not talking about men who were defeated; we are talking about men who were victorious, men who won.

We should never forget it.

Of course, if it could be argued that the price of their victory was especially exorbitant, that the casualties suffered were exceptional, unparalleled, that would indeed reduce the quality of the victory, and their achievement. But no such thing can be argued. There was absolutely nothing exceptional about the British casualties. Oh yes-w e did endure the worst single day, probably in the history of war — July 1 1916, with its horrific 57,000 casualties. But as I said in The Smoke and the Fire, it was just one day in the war lasting over 1,500 days - and it was a freak. Nothing like it ever happened again. And a day is only a span of time - no more significant than any other.

What about a week? I cited a week in July 1916 when the Austro-Hungarians are believed to have lost nearly 300,000! A fortnight? The French definitely lost 200,000 in the last two weeks of August 1914. A month? Well, the 31 days of July 1916 including the horrors of July 1 cost the British 164,709; the Italians lost more than that -165,000 - in a 26-day span in 1917. Six weeks? Between March 21 and April 30 1918 the Germans lost 348,300. A year? In 1915 Russia lost about 2 million. And the war totals tell the same story.

The Italian dead in 3 years on their single front are not far short of the United Kingdom dead on the Western Front in four years. The French dead amounted to 3.5% of their total population. The German to about 2.9%. The British (United Kingdom) to 1.9%. It is thus demonstrably false to accuse the British generals of causing their men to lose more heavily than the other armies that faced the same problems at the same time - which is the only rational comparison.

It was, indeed, a war of terrible casualties. Don't let us make any mistake: it was not the war of the most terrible casualties. That was World War II - which cost about four times as many lives as World War I. The largest particular numbers were sustained in great battles of unprecedented ferocity, which were, in fact, the Verduns, the Sommes, the Passchendaeles of that war - only they were called Leningrad, Stalingrad, Sebastopol, Kursk, Orel, and names likes that.

Let me give you just one comparison:

The Battle of Verdun, in 1916, is always considered to have been one of the conspicuous blood-baths of World War I. Captain Cyril Falls wrote: "For sheer horror no battle surpasses Verdun. Few equal it." (8) On that narrow front of about 20 miles along the Meuse, between February and December 1916 - yes, the fighting went on for ten terrible months - the French and Germans between them lost about threequarters of a million men. In 1941, in the six opening months of their attack on the Soviet Union, the Germans alone lost that number. Too often we hear the false comparison between the wars. Let us get it straight at last: the Second was bloodier by far.

However, that does not alter the fact that the First World War was very bloody indeed, a horrifying experience. It was, in fact, the first war of the real mass armies, drawn from the mass populations which accompanied the Industrial Revolution, and the casualties were on a corresponding mass scale.

It was a French general, General Mangin, who after comparing the losses of his own and neighbouring divisions in attack and defence, came to the gloomy conclusion which may stand as an epitaph of the whole war, he said:

"Quoi qu'on fasse, on perd beaucoup de monde." ("Whatever you do, you lose a lot of men.")

He was right.

And one reason why generals, of all nations, try as they might, did not seem able to avoid heavy losses in battle was that they all suffered - as I said in The Smoke and the Fire, and again in my latest book, White Heat, (9) - from a unique disadvantage. It was the only war that has ever been fought without voice control. The result, as I said, was that.

"Generals became quite impotent at the very moment when they would expect and be expected to display their greatest proficiency."

As their men entered the battle, they passed out of the control of their generals for hours, sometimes for days. The only place where control could be exercised as at the centre of a telephone network. But telephone lines are very vulnerable. And telephones cannot accompany a moving battle line.

It was check-mate.

Add to that the constant inflow of new weapons and new systems, the endless contributions of technology to the complication of war, and you begin to take the measure of that unique problem faced by all the world's generals. And finally, for full measure, bear in mind that although technology had perfected ways of bringing unprecedented numbers of men to the battlefield, it had still to go a further stage to enable them to move once they got there. Meanwhile, for movement, the armies relied chiefly on the legs of men and horses - both of them very vulnerable. Small wonder if it was hard going.

Nevertheless, the British generals soldiered on, and in 1916 they took up the task which the French had performed for the first two years: they engaged the main body of the main enemy on the main front of the war. It had cost the French appalling casualties in 1914 and 1915 to do that. It cost the Russians appalling casualties to do the same thing between 1941-45. If it had not cost us appalling casualties, that would have been a miracle requiring a supernatural explanation. But the British Army, generals and soldiers alike, was not composed of supernatural beings, just humans. Its experience was the normal human experience of that war.

Its achievement, however, under those much-maligned generals, Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, General Sir Henry Horne of the First Army, General Sir Herbert Plumer of the Second Army, Sir Julian Byng of the Third, Sir Henry Rawlinson of the Fourth and Sir Hubert Gough of the Fifth (to name the ones most concerned) between 1916-18 was an achievement unparalleled in our history.

In 1916, on the Somme, the BEF engaged 95V2 German divisions, over 40 of them twice, some three times. In 1917, in the Battle of Arras and the Flanders Campaign, it engaged 131 German divisions.

In March-April 1918 the Germans attacked it with 109 divisions. In its own Final Offensive, August - November, it engaged 99.

No other British generals have ever faced such an array of sheer force in battle. That is why comparisons with World War II are pointless; there are no comparisons for the British Army.

Let me give one example only:

On March 21 1918, General Sir Julian Byng and General Sir Hubert Gough were attacked by 50 identified German divisions on that single day. No British general of World War II ever saw 50 German divisions, or anything like that number. The only one who ever even glimpsed the main body of the German Army during that war was Lord Gort, in May and June 1940. Even my beloved "Bill" Slim won his famous Burma victory over only about 9 Japanese divisions — out of an Order of Battle of 174. It makes things very difficult, doesn't it? Comparisons are useless, unless you can compare like with like; but there is nothing in our history like the role of the British Army on the Western Front in World War I.

And there I'm going to end - you probably think, "about time too". Let me just add this: I am not in any way suggesting that our generals were supermen: of course they made mistakes; of course they had bad days; of course a task like that tested them to the limits. This goes for all of them, and I think I cannot conclude better than by quoting what Winston Churchill said about Lord Haig, the Commander-in-Chief: "He might be, he surely was, unequal to the prodigious scale of events; but no-one else was discerned as his equal or his better." (10) Looking at their contemporaries, I think you could say that of all our generals at the end of the war - and what more could you say?

NOTES

(1) : Gwynn (Stephen) ed. The Anvil of War: Letters between F.S. Oliver and his Brother 1914-18. Macmillan, 1936. p.124.

(2) : Military Operations: France and Belgium 1917. [Vol. I], Compiled by Capt. Cyril Falls. Macmillan, 1940. p.479.

(3) : Sassoon (Siegfried) Counter-Attack and other poems. Heinemann, 1918. p.26. The holograph mss. is dated May 1917.

(4) : Lloyd George (David) War Memoirs. Nicholson & Watson, 1933-1936. 6 vols., 3531pp.

(5) : Terraine (John) To Win a War 1918: The Year of Victory. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1978.

(6) : Slim (1 st Viscount) Defeat into Victory. Cassell, 1956. p.121.

(7) : Terraine (John) The Smoke and the Fire: Myths and Anti-Myths of War 1861-1945. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1980. p.214.

(8) : Falls (Cyril) TheFirst World War. Longmans, 1960. p. [156].

(9) : Terraine (John) White Heat: The New Warfare 1914-18. Sidgwick& Jackson, 1982.

(10): Churchill (Winston S.) Great Contemporaries. Macmillan, 1938. Rev.edn. p.230.