The George Cecil Memorial at Villers-Cotterets by Michael Aidin

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The George Cecil Memorial at Villers-Cotterets by Michael Aidin

[This article first featured in Stand To! No.74 September 2005 pp 35-36. Some additional images have been added].

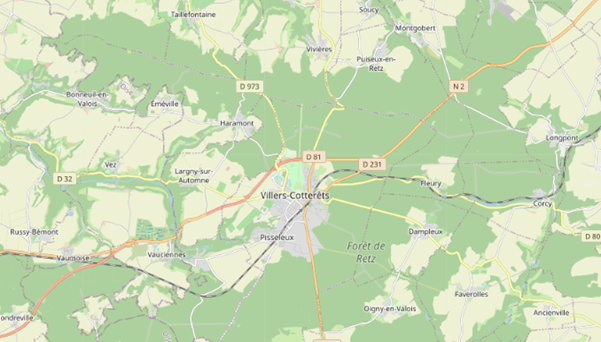

The memorial (below) to Lieutenant George Cecil by Francois Sicard (1862- 1945) is one of the finest private monuments erected on the Western Front. Situated in the extensive Foret de Retz at Villers Cotterets, about 20 miles from Compiegne, the monument is close to a small cemetery containing about 100 graves of officers and men of the Grenadier, Coldstream and Irish Guards killed on 1 September 1914.(1)

Rudyard Kipling in his Irish Guards in the Great War wrote of the site:

'...perhaps the most beautiful of all resting-places in France, on a slope of the forest off the dim road, near the Rond de la Reine, holds our dead in that action.' (2)

Although the monument is fine, the story behind it is particularly interesting. Why was such a distinguished monument put up to one of the millions of the young men killed in France in what, to the British, is the most terrible of all wars?

The Cecil Monument consists of a statue of a woman dressed in the style of Ancient Greece, studying a stone carving on what may be the grave of a soldier. The statue is similar to that known as the 'Mourning Athena' from the Acropolis in Athens. Traditionally, this was considered to be the Goddess Athene studying the list of Athenian dead from the Battle of Marathon in 498 BC. Here the figure, leaning on a pilgrim staff, is studying a contemporary army helmet, presumably on the grave of someone dear to her.

The inscription below the statue reads: 'Passant, arrete-toi', words from a poem by La Fontaine, which may be translated as 'Stop, you who pass by'.

On the reverse side the following is carved:

IN HONOUR OF THE OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE GRENADIER, COLDSTREAM AND IRISH GUARDS WHO FELL NEAR THIS SPOT ON 1ST SEPTEMBER 1914. THIS MEMORIAL WAS PLACED HERE BY THE MOTHER OF ONE OF THEM, AND IS ESPECIALLY DEDICATED TO SECOND LIEUTENANT GEORGE EDWARD CECIL.

Francois Sicard, winner of the Prix de Rome, was a well-known French sculptor of the period. Probably his most famous war memorial work is the Archibald Fountain in Sydney, New South Wales. He also executed important memorials in France at Blois and Fecamp.

George Cecil

George Cecil was a grandson of the third Marquess of Salisbury, who was Prime Minister three times. George was one of five of his ten grandsons who were killed in the war and was the only son of Lord and Lady Edward Cecil.

Lord Edward Cecil started life as a soldier, a Grenadier, and later became an official in the British civil service in Egypt. Lady Edward was born Violet Maxse, the daughter of Admiral Maxse, a hero of the Crimean War and a well known atheist and radical. Her brother, General Sir Ivor Maxse, became Inspector of Training in the Great War. Violet had been brought up by her father (her parents were separated), partly in Paris, where she had studied art and music, and she knew many prominent people including Degas, Rodin and Georges Clemenceau. Violet was a clever and intrepid young woman: she climbed the Eiffel Tower while it was under construction, not the act of a conventional girl in Victorian times. In 1932, on the death of her brother Leo, Violet took over the editorship of the National Review, a political journal, and retained the position until 1948.

The very Christian Cecil family were disconcerted by their son's atheist bride. Violet was sent to be instructed in Christianity by Dr Winnington-Ingram, the future Bishop of London. 'I spent some hours with him' she wrote 'and I was not asked to go again'.

George Edward Cecil's death and burial George

Cecil was still only 18 when he went to France on 13 August 1914 with his father's old regiment. The Grenadiers were involved in heavy fighting in the forest near Villers-Cotterets.

On 1 September, George Cecil was killed, sword in hand, leading a bayonet charge.

First reports were that he had been wounded and taken prisoner. Elaborate enquiries were made about his fate. One can see the British class and social system of the period in operation. Rudyard Kipling, who was a neighbour of the Cecils in Sussex, questioned British soldiers who had survived the battle for news of George Cecil. Lord Milner, whom Violet Cecil married after her husband's death in 1918, and who spoke fluent German, interrogated prisoners of war. Lord Kitchener arranged for the American Ambassador in Berlin to make enquiries of the German authorities. When no information was forthcoming, Lady Cecil decided to go to France to make enquiries on the spot. Clemenceau (who had befriended George when he visited Paris as a schoolboy) sent a series of telegrams authorising her to enter a military zone (fighting was still taking place not far away). Later in September, Lady Edward went to Villers-Cotterets in the American Ambassador's car, escorted by his military attache. This expedition did not produce firm information, although a communal grave dug by the German Army had been found in the forest. Violet described her visit in a letter of 1 October. Violet Cecil also wrote that she saw her son in a dream and talked to him about what had happened, but this vision did not recur.

In November 1914 Lord Killanin (brother of Colonel Morris of the Irish Guards who had been killed in the fight) went with Lord Robert Cecil MP, uncle of George Cecil, who was working for the Missing and Wounded Department of the Red Cross, Lord Elphinstone and an English clergyman from Paris, to find the remains of the men who had died. The common grave was opened. The bodies of four officers and 94 men were found and the bodies of most, including George, were identified. In view of the time since burial and the wounds on the bodies, this was a gruesome and distressing task. The men were reburied in the forest. Coffins were obtained for the bodies of the officers and conveyed to the cemetery at Villers-Cotterets.

A funeral service, attended by the Mayor of Villers-Cotterets, other civil officials, a French Colonel and some 20 French soldiers, took place. In the background was the constant sound of artillery fire from the Front, not far away on the Aisne. Lord Killanin was asked to follow the French custom, and, as a relative of the deceased, stood at the entrance to the cemetery; as those who had attended the funeral departed he shook hands with them and thanked them for coming. He reported that the French made many most kind and touching remarks, saying that their presence was the least they could do to honour the brave English officers who had fought and died in their country in the common cause.

With the identification of George's body, Violet's last hope disappeared. A telegram from the Kiplings said 'We are thinking of you always and desolate to think that we can no longer help. Rudyard and Carrie'. Lord Curzon, former Viceroy of India, wrote full of sympathy to 'My poor dear Violet'.

Memorials

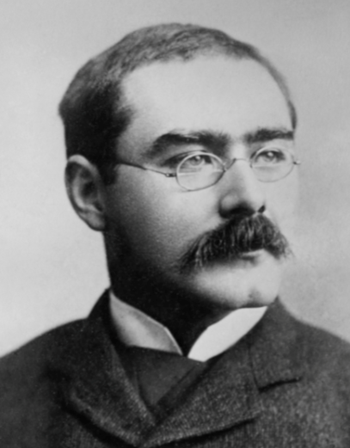

In 1915 the Cecil Rifle Range was opened by Rudyard Kipling as a memorial at Winchester College, George's old school. Rudyard Kipling fired the first shot and scored a bullseye, and was enthusiastically cheered by the boys. (This seems a considerable achievement for a man with poor eyesight, who had to wear strong spectacles.) Kipling, in his speech, said to the boys:

You have seen and realised the very things which young Cecil felt would befall. As far as his short life allowed he ordered himself so that he might not be overwhelmed by them when they were upon him. He died - as many of you too will die - but he died knowing the issues for which he died. It is well to die for one's country. But that is not enough. It is also necessary that as long as he lives a man should give to his country, as George Cecil gave, a mind and a soul neither ignorant nor inadequate. (3)

George Cecil had been given a crucifix at his confirmation by his uncle Lord Hugh Cecil (later Provost of Eton) on which after his death his father had engraved the triumphant epitaph 'Died for his country on 1 September 1914 near Villers-Cotterets in France having continued Christ's faithful soldier and servant until his life's end'. 20 years later Violet gave a sixteenth-century painting of the Crucifixion to the chapel at Hatfield House in memory of George and his father.

In 1922, the monument at Villers-Cotterets was erected. After the war, the bodies of the officers and men were reburied in a British military cemetery (Guards Grave, Villers-Cotterets Forest) close to the Cecil monument. Gravestones were placed on the inside of the wall surrounding the cemetery, and here one sees some of the most famous names of the British aristocracy - a Cecil, a Lambton (grandson of the Earl of Durham) and that of Colonel Morris, Lord Killanin's brother.

When I visited the cemetery I found a note from the present Lord Killanin - a distinguished Irish film producer, Redmond Morris - saying that he had come from Dublin to visit his grandfather's grave.

The photograph of the monument was taken by Dillon Bryden, a professional photographer, and a great-grandson of Colonel Morris.

In his History of the Irish Guards in the Great War Kipling wrote:

The death of Colonel Morris, an officer beloved and a man noticeably brave among brave men, was a heavy loss to the Battalion he commanded, and whose temper he knew so well. In the thick of the fight during a lull in the firing, when some blind shell-fire opened, he called to the men: ‘D 'you hear that? They're doing that to frighten you'. To which someone replied with simple truth: 'If that's what they're after, they might as well stop. They succeeded with me hours ago’ (2)

Stained-glass windows in their memory were installed in churches near the homes of Colonel Morris in Ireland and Lt Lambton in England.

A portrait of George Cecil as a boy by John Singer Sargent hangs in the Musee Clemenceau at Clemenceau's flat at 8, Rue Franklin in Paris. Thus several individuals were commemorated in a number of places and in many different ways. One wonders how many of the tourists who pause on the roadside at the monument in the Foret de Retz, or who see Sargent's portrait of George Cecil in Clemenceau's flat in Paris, know the whole background.

The little 'Guards Grave' cemetery encapsulates the tragedy of 1914 for Britain, for its Empire and for its ruling class.

Violet, until she became very old, made a pilgrimage to Villers Cotterets every year except 1941 / 44.

Sources:

1.Thorpe, B: Private Memorials of the Great War on the Western Front (Published by The Western Front Association).

2. Kipling, R: Irish Guards in the Great War.

3. Kipling, R: Speech 1915, The Wykehamist.

4. Cecil, H & M: Imperial Marriage (2002).

5. Craster, J M: Fifteen Rounds a Minute: the Grenadiers at War 1914 (1968).

6. Violet Milner Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.