The Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine

In 1847 the British authorities in Hong Kong began using Indians as gun lascars, or general workers, because the climatic conditions were unsuitable for white soldiers, and also because Indians were much more economical to employ and to administer. The practice spread throughout the British possessions in the Far East and by 1908 all the gunners were Sikhs or Muslims recruited from the Punjab. The quality of recruit was excellent as the pay was higher than that offered by the Indian Army, and also there was prestige involved in manning field or larger guns that were not used by Indian Army units. In that year a British Army Imperial [1] unit named The Hong Kong-Singapore Battalion Royal Garrison Artillery was formed with three companies in Hong Kong and one company each in Singapore and Mauritius. The gunners were focused towards coastal defence duties but some of them had been employed as machine and mountain gunners during operations in China in 1900 and 1901. After that conflict [2] ended permission was requested to maintain a mountain battery in Hong Kong, but London dismissed the idea. Eleven years later action was taken and the 24th Hazara Mountain Battery, Frontier Force, Indian Army, arrived in Hong Kong in 1912. When that battery departed in 1914 it left behind a trained company of mountain gunners, No 1 Company, in the Hong Kong-Singapore battalion.

Above: HK&SRA shoulder badge

After war had commenced in 1914 the commander of No 1 Company requested an overseas operational deployment for his sub-unit. This was granted in September 1915 when the War Office requested a four 10-pounder gun [3] battery be deployed to Egypt; the number of guns required was then increased to six. No 1 Company was the nucleus of this new battery but drafts were allotted from No 4 Company in Mauritius and No 5 Company in Singapore; there was keen competition throughout the battalion to be selected for this deployment. The battery strength was: 3 British officers, 3 Indian officers, 205 Rank and File and a few British non-commissioned-officer (NCO) specialists. Initially mules were the pack animals. The battery embarked at Hong Kong on 8 November 1915, called in at Singapore to collect the draft from that station, and disembarked at Suez; the draft from Mauritius joined in Moascar near Ismailia where the battery was attached to the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade. Initially the Right and Centre Sections were employed along the line of the Suez Canal.

The Senussi invasion of the Egyptian Western Desert

The first threat that the Hong Kong-Singapore gunners faced did not come from the east [4] but from the west, where Turks and Germans had incited the Senussi to invade western Egypt from Libya [5]. Fighting had started in December 1915 and the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery was deployed to Sidi Barrani on 7 March 1916. However by now the Senussi along the coast had lost too many men and too much ground and they were dispirited. The battery joined in the British advance towards the Libyan border but did not fight, although the experience of operating in the desert on long marches was excellent preparation for the battlefields that lay ahead. In April most of the British Western Frontier Force moved back towards the Canal, but a small detachment including a section of the battery remained for a time to garrison Sollum.

Above: Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery in action

Into action in the Eastern Desert

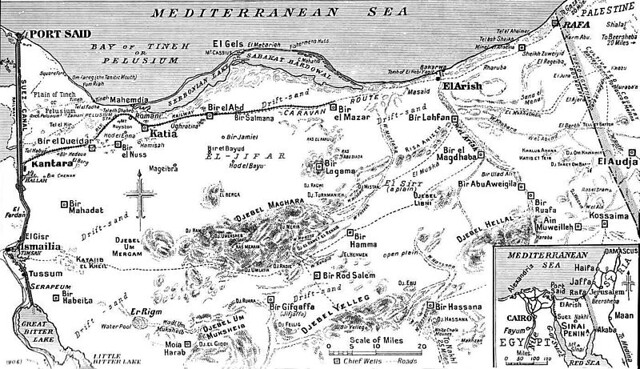

As 1916 developed the British commenced advancing over and occupying the coastal areas of the desert east of the Suez Canal. A railway was constructed and also a water pipeline, whilst wire netting stretched over the sand alongside the rail line provided a suitable road for both vehicles and marching men. British aeroplanes made reconnaissance flights, but had to be careful because of the superior performance of the German planes used by the enemy [6]. The Turks reacted to the British pressure, capturing a Yeomanry garrison at Qatiya (Katia) in April whilst unsuccessfully attacking Romani in July; they then withdrew their main force eastwards to El Arish, leaving outposts at waterholes.

Above: Map of the Eastern Desert

In an attempt to demonstrate British superiority in the northern Sinai Desert two small raids were mounted on isolated Turkish positions during the Autumn of 1916, and the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery was involved in both raids. On 17 August, two Australian Light Horse brigades, three companies of Imperial Camel Corps, with two horse artillery batteries and one section of the Hong Kong-Singapore battery in support, attacked Bir (well) El Mazar on the track to El Arish. But the Turks were prepared and the British horse batteries were misled by a guide so the British commander, Major General Sir H G Chauvel KCMG CB, broke off the action and returned to base. Shortly afterwards the Turks withdrew their post from Bir El Mazar.

The second raid, on 15 October, was a more daunting proposition against Bir El Maghara, which was 80 kilometres south-east of Romani and surrounded by difficult ground. Major General A G Dallas CB CMG commanded two regiments of Australian Light Horse, the 1st City of London Yeomanry, 300 men of the Imperial Camel Corps and a section of the Hong Kong-Singapore battery. The British force deployed from Bir Bayud and made two night marches before attacking. An advanced enemy post was taken and 18 Turks captured, but the enemy main body was in a well-fortified position on the steep slopes of Jebel (mountain) El Maghara. After exchanging fire for a couple of hours, General Dallas broke off the engagement and withdrew. Both Generals commanding these raids had been ordered not to become involved in heavy fighting with strong enemy positions, but the Hong Kong- Singapore gunners had come into action and had been able to test their drills and operational procedures. The Battery then moved to Abbasia where the mules were handed in and replaced by camels; each of the three sections receiving an animal strength of 3 horses, 73 riding camels and 47 pack camels.

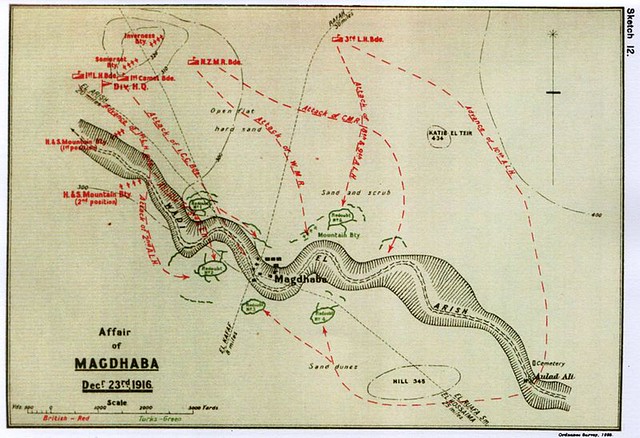

The actions at El Maghdaba and Rafah

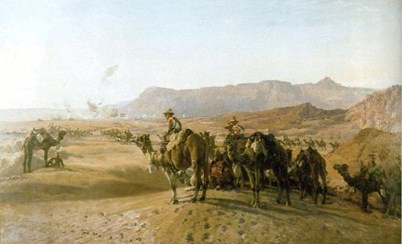

The next British objective along the coast was El Arish but as the Turks had a railhead at El Kossaima the British decided to also attack El Maghdaba in between El Arish and the railhead. On 19 December 1916 the Imperial Camel Brigade was formed from the Imperial Camel Corps. In the brigade were four battalions [7] of camel infantry, a machine gun company [8], an engineer troop, a field ambulance [9], a signal section and administrative and logistic elements; the gunners in the Brigade were the Indians of the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery. Each infantry battalion had a section equipped with three Lewis light machine guns. The Brigade Commander was Temporary Brigadier General C L Smith VC [10] MC, of the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry.

Above: Camel Corps at Maghdaba by H S Power

On 20 December the British occupied El Arish which had been abandoned by the enemy, and then advanced up the El Arish Wadi (valley) to attack Maghdaba three days later. The attack was commanded by General Chauvel who used most of his Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division and the Imperial Camel Brigade. The Turks manned five strong redoubts on dominating ground above both sides of the wadi and the British plan of attack engaged every redoubt and cut-off likely enemy retreat routes. The Turks held strong positions but a large number of their Arab soldiers fled from the battlefield during the action, lowering the morale of those who stayed to fight. After some tense moments throughout the day, especially as regards the very limited water supplies carried by the British troops, Chauvel's men seized all the enemy positions by 1630 hours, having lost 146 men and 51 horses killed or wounded. Turkish losses were 97 killed and 1,282 taken prisoner. The Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery had performed well, advancing as the battle developed from its initial gun position north of the wadi to come into action again in a second position south of the wadi.

Above: Maghdaba Action sketch map

The following four gallantry awards can be attributed to the Maghdaba action:

- Distinguished Service Order to the Battery Commander, Major William Agnew Moore, Royal Garrison Artillery: For conspicuous gallantry in action. He handled his battery during the action with marked skill, thereby clearing a redoubt which was checking the infantry advance.

- Imperial Distinguished Conduct Medal [11]. Three awards to Havildars:

- No. 712 Havildar Piran Ditta. For conspicuous gallantry in action. He displayed great courage and determination throughout the engagement under very heavy fire. He has at all times set a fine example.

- No. 722 Havildar Nawab Khan. For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. On two occasions he displayed great courage and coolness under heavy fire. He has at all times set a splendid example.

- No. 1050 Havildar Fatteh Singh. For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He displayed great coolness under fire, and set a fine example of determination on the night marches which the operations entailed.

The occupation of El Arish allowed the Royal Navy to land supplies on the beaches there until the railway and water pipeline construction teams reached the town. The commander of the British Desert Column who was spearheading the British advance, Temporary Lieutenant General Sir P Chetwode, Baronet, CB DSO, decided to personally lead an attack on Rafah on the Palestinian border. The Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division, the Imperial Camel Brigade and the 5th Mounted Brigade [12] were the attacking troops who advanced during the night of 8 - 9 January 1917. Security was maintained until dawn when the inhabitants of Arab desert encampments saw the British advance and passed the information across the desert from camp to camp and to the enemy by verbal ululations.

The Turks, with a few German advisors, held strong fortified positions at Rafah on the western side of the border. The British surrounded the enemy posts and commenced attacking over very open ground at 0930 hours. Again water supply was a major distraction for the British, as the wheeled supply transport had been left 15 kilometres to the rear at Sheikh Zowaiid. The British attacks made little progress against effective enemy shrapnel and machine gun fire, and reconnaissance patrols reported that Turkish troops were advancing from the north-east to relieve Rafah. In the mid-afternoon General Chauvel sent his mounted New Zealanders to make a fresh attack on the key enemy position, the Reduit, and he was discussing the likely necessity of a withdrawal [13] by field telephone with General Chetwode when New Zealand bayonets were observed going in hard over the Reduit slopes. Turkish hands swiftly rose in surrender and the crisis was over. The other enemy positions then fell, the Imperial Camel Brigade taking its objectives in another bayonet charge; the British troops now accessed the water sources previously denied to them by enemy fire.

The British wounded [14] and the guns of a captured Turkish mountain battery were brought in and General Chetwode withdrew his exhausted force. However, British air patrols on the following morning reported that the enemy had not re-occupied Rafah so a return was made to the battlefield to recover the abandoned Turkish material [15] that had not already been removed by local Arab looters. Enemy prisoners taken at Rafah numbered 1,635 [16] including the Turkish commander and 11 Germans. The British casualty total was 71 officers and men killed, and 414 officers and men wounded with 1 man missing; Rafah had proved to be a much tougher nut to crack than El Maghdaba. After Rafah the battery replaced its old 10-pounder guns with six 2.75-inch guns [17].

The First Battle of Gaza

The British theatre commander, Lieutenant General Sir A J Murray KCB GCMG CVO DSO, was under instructions from London not to advance into Palestine and capture Jerusalem until the Autumn of 1917. However both he and General Chauvel wished to attack Gaza and destroy the enemy garrison there before the Turks withdrew it. Gaza was just over 30 kilometres distant from Rafah. The British commander of the Eastern Force, Temporary Lieutenant General Sir C M Dobell [18] KCB CMG DSO, was ordered to seize Gaza and its garrison by a coup de main; the resources with which he had to achieve this task were two mounted divisions, three infantry divisions and the Imperial Camel Brigade. However General Dobell had an inadequate number of both staff officers and artillery guns, and he had the normal problems associated with water and ammunition supplies that occurred when British forces advanced beyond their railhead [19].

Above: Turkish artillery in Palestine

A preliminary British objective was the occupation of the line of the Wadi El Ghazze, which was to be held to protect the advancement of the railroad, and this was achieved before first light on 26 March 1917. However, dawn saw dense fog rolling up the wadi from the sea, reducing visibility to around 15 metres distance, causing confusion for a time amongst the advancing troops. The timetable in the battle plan was permanently disrupted as the scheduled hours for reconnaissance and the issuing of orders had been lost due to the fog, resulting in the loss of valuable hours of daylight for Dobell's formation commanders to deploy and attack. But the mounted troops pressed on, the fog started lifting at around 0800 hours, and by 1030 hours Gaza was enveloped. The Turkish general commanding the enemy 53rd Division was captured by Australian light horsemen during this envelopment, but the general's division was behind him and it continued marching towards Gaza.

By noon General Chetwode's mounted troops were well forward but he became concerned at the slow deployment of the British marching infantry divisions. This concern was compounded by information from a prisoner that the Gaza garrison was not just two battalions as the British had believed, but that six battalions were holding the town; reconnaissance patrols reported that Turkish reinforcements were on their way. However the battle proceeded at its own pace, and by nightfall the enemy positions at Ali Muntar immediately south-east of the town had been taken despite some fierce resistance. Gaza was surrounded but Turkish reinforcements were closing-in from the north-east.

Unfortunately, the British chain of command across the battlefield, its reporting systems, its battle procedures and its required liason between formation commanders were all not functioning effectively, and the senior British commanders became pessimistic because of the paucity of corroborated information. British intelligence officers back in Sinai possessed the Turkish cypher key and they intercepted and translated most enemy messages speedily, but the British telegraph system then failed to quickly forward them to General Dobell. Lack of water for the horses weighed heavily on the minds of senior officers, as did the fear of Turkish reinforcement arriving. Despite significant gains by the infantry and the mounted troops a decision was made to withdraw back across the Wadi El Ghazze if Gaza had not been seized by last light, and although hindsight shows that much of the ground taken did not have to be surrendered, the British troops left the battlefield during 27 March. The British force had lost 523 officers and men killed, 2,932 wounded and 512 missing. The enemy casualty figure totalled 2,447 Turks, Germans and Austro-Hungarians killed, wounded and missing.

Unfortunately, in his report to London, the British theatre commander, who had been following events from a train on the new Eastern Desert railway line, down-played the various difficulties that had overwhelmed the British command and control system, and predicted that a swift second attempt would unhesitatingly take Gaza. This resulted in a change of attitude in London and General Murray was authorized to advance on and capture Jerusalem but, sadly, his Egyptian Expeditionary Force was not either ready or competent to undertake such a task.

During the First Battle of Gaza the Hong Kong-Singapore gunners had been involved in some fierce fighting as the Imperial Camel Brigade fought the rearguard actions on 27 March that allowed other formations to safely withdraw across the Wadi El Ghazze.

The Second Battle of Gaza

A three-week pause occurred whilst the British prepared for a second attack on Gaza; during this breathing-space the Turks positioned good units forward of and to the east of Gaza, resulting in 18,000 men being ready to meet the next British move. The British Eastern Desert rail line was extended to a railhead just behind Wadi El Ghazze and more artillery was deployed forward; however, there was insufficient ammunition available although 4,000 gas shells were distributed to some of the British artillery units. Again, British air reconnaissance was subject to interdiction by superior German planes [20] but successful aerial photography resulted in a new partially-contoured map being produced for British commanders. Off the coast the French navy positioned ships to provide fire support, as this part of the Mediterranean coastline was in the French naval zone.

Above: Turkish Gunners - 2nd Gaza

General Dobell did not attempt to turn the enemy inland flank, presumably because of perceived water-supply restrictions, and he rejected the view of some of his infantry commanders who wanted to punch powerfully up the coastline, as he saw no influential employment for his mounted troops in that tactic. On 17 April the British force of two mounted and three infantry divisions advanced to locations from where it could launch frontal attacks. On 18 April the attacking troops halted whilst the British artillery and the French navy bombarded Turkish positions, using gas [21] to try to neutralize enemy gun lines. On 19 April the attacks went in but it was immediately obvious that the previous day's bombardments had done very little to disrupt the Turkish artillery or to cow the Turkish defenders of strong-points. British attacks were repulsed or only made ground at a high cost in casualties.

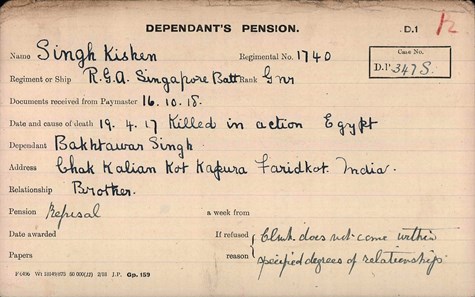

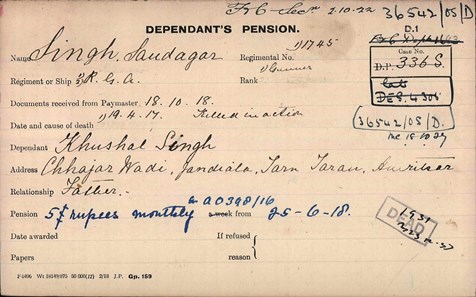

In this battle the Imperial Camel Brigade was attached to, and attacking on the right flank of, the British 54th Division. The Brigade objective was a redoubt 1.5 kilometres north-west of Khirbet (ruins) Sihan. A British tank [22] supported the assault on the redoubt but it was hit repeatedly and burst into flames. Then infantrymen got into the redoubt, now nick-named 'Tank Redoubt', but most of them were killed by enemy fire or counter attacks. Other infantrymen of the Brigade crossed the Gaza-Beersheba road and temporarily established themselves on two hummocks nick-named 'Jack' and 'Jill'; the mountain battery provided close fire support throughout these actions and took casualties. Lieutenant Ben Fletcher Chapman of the battery was killed in action whilst acting as a Forward Observation Officer; Gunners 1704 Kishn Singh and 1745 Saudagar Singh were also killed and several others were wounded.

Above: Disabled British tank after the 2nd Battle of Gaza

By now the British ammunition shortage was being felt and effective Turkish counter-attacks were being delivered including a spirited cavalry attack on the Desert Column operating on the British right flank. It was obvious to the British divisional commanders that there was no chance of a success on the battlefield and that more casualties would be taken for little gain if the fighting went on next day. From Khan Yunis in the rear the theatre commander, General Murray, wanted the ground that had been taken to be held and General Dobell ordered his troops to dig-in where they were. The Second Battle of Gaza ended at this point, the British having lost 509 men killed, 4,259 wounded and 1,576 missing; the Imperial Camel Brigade had taken 345 casualties. Three British tanks were lost out of the eight deployed and 2,129 British animals were casualties. The triumphant Turkish defenders had lost 402 men killed, 1,364 wounded and 247 missing, but they had ensured that the British Eastern Force was not in a fit state to take Jerusalem.

On 21 April General Murray moved quickly to focus the blame elsewhere, dismissing General Dobell on health grounds and sending him back to England; General Chetwode was appointed as the new commander of the Eastern Force. But, on 11 June, General Murray himself was ordered to return to England and he was replaced as Theatre Commander by General Sir E H H Allenby.

Beersheba to Jerusalem

General Allenby, a cavalry expert, revitalised the British force after its misfortunes at Gaza, and he created a new Desert Mounted Corps under Lieutenant General Chauvel that included the Imperial Camel Corps. Allenby decided to prise the Turks out of Gaza by first taking Beersheba in the desert on the enemy eastern flank. The Desert Mounted Corps took Beersheba in a charge on 31 October 1917 but the Imperial Camel Corps was on detached duty further to the west and the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery was not involved in the fighting. A third attack on Gaza was then successfully launched on 6 November; after a heavy British bombardment the Turks slipped away in the night leaving behind only a few worn out guns.

The next British objective was Jerusalem. During this operation the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery was attached to the Australian Mounted Division as the ground to be crossed was too rough for the division's wheeled artillery and transport. The ground was also rough for camels. When, on 21 November, the East Riding Yeomanry from 22nd Brigade was ordered to advance on Ram Allah Hill, a section of the battery was attached in support; the ground was rocky, boulder strewn, often precipitous and was slippery from regular rainfall. The Official History contains an eye-witness account of the Hong Kong-Singapore gunners in action:

The section attached to the 22nd Brigade by sheer determination got their little gun as forward as El Muntar [23]. Their camels' feet were bleeding, and as they progressed by the narrow wadi beds it was not an uncommon sight to see them practically lifting their animals laden with ammunition over high boulders and rock which obstructed the path. They started dauntless and remained undaunted . . . Even when they were actually in action, each time they fired their gun a cloud of black smoke gave away their position, and they were replied to by batteries which they could not reach with shells that came over them like coveys of partridges. . . . Yet, despite the fact that on account of range they could really do little damage, they continued to invite destruction all through the afternoon.[24]

This particular operation was aborted but the battery remained up in the hills; however it was doubtless cheered-up by the sight and companionship of Indian Army units who were now reinforcing the British troops in Palestine. On 1 December, a Turkish attack penetrated the line north-east of El Burj held by the 8th Australian Light Horse. The situation was saved by a fierce Australian defence, the rapid arrival of aggressive reinforcements and the steady fire of the Hong Kong-Singapore gunners. Seven days later the successful British attack on Jerusalem commenced, the battery proving its worth up in the hills with its ability to closely follow the infantry and the mounted troops – a decisive factor that the wheeled batteries could not emulate.

Three more awards of the Imperial Distinguished Conduct Medal can be attributed to the Jerusalem area actions:

- No. 762 Havildar Sultan Mohamed: For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When his section was subjected to very heavy shell fire, which eventually made it necessary to withdraw the guns, his gallantry, fine example, and devotion to duty were most marked.

- No. 1081 Havildar Piran Ditta: For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He showed great coolness and determination when an ammunition convoy of which he was in charge came under heavy shell fire during an action. His cheerfulness and good example have been an inspiration to his section on several occasions.

- No. 1213 Havildar Chajja Singh: For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When his section was forced to retire over very difficult country and during a period which became increasingly critical owing to enemy pressure, his gallantry, coolness, and devotion to duty proved of inestimable value during this withdrawal.

The final year in Palestine

On 5 January 1918 the battery rejoined the Imperial Camel Brigade at Rafah where a period of rest and refurbishment was programmed. All equipment was thoroughly overhauled; saddles were taken to pieces and the pads re-stuffed and fitted to suit the backs of the camels, whilst all leather work was renewed as necessary and oiled, dubbined and polished. Camels were inspected by veterinary specialists and the guns were meticulously stripped, cleaned, inspected and serviced. Casualty replacements joined the battery.

In March the Imperial Camel Brigade moved north and entered a region full of significance to the Christian infantry soldiers who were familiar with biblical tales. On the 23rd of that month Jericho was reached, the Jordan Valley crossed, and a point less than a kilometer from the Dead Sea reached. Gunfire from ahead signaled where fighting was taking place and dead Turks, stripped of every piece of clothing by the local inhabitants, lay beside the tracks. As the hills on the east side of the Jordan Valley were climbed the wheeled artillery started to turn back to find other routes, but the battery camels maintained their pace with the infantry.

Above: Imperial Camel Corps crosses the River Jordan to attack Amman

The author [25] of The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, 1914–1918 later wrote:

Immediately after leaving the foothills, General Smith was obliged to dismount his force, and all night the men of the three Battalions (and of course the battery) dragged their camels up the mountain-side. The men hauled and urged, the camels slipped and fell, but still fought steadily on. The Brigade straggled in single file almost from the valley to the Plateau, winding its fantastic course along crooked and flooded wadi beds, and treading narrow ledges round the sides of hills. In peace time such a feat would have been deemed impossible by any Eastern master of caravanning; but under the brutal lash of war the Brigade went surely up to the tableland.

The purpose behind this trek was for one battalion to demolish a portion of the Hedjaz railway south of Amman whilst the remainder of the brigade took part in a raid designed to seize the city. Several kilometres of rail track were disrupted by the demolition battalion blowing culverts but the attacking force soon had its hands full with fierce Turkish resistance; the Hong Kong-Singapore battery was the only artillery unit firing in support. The Imperial Camel Brigade advanced to within 230 metres of the enemy trenches defending Amman but was then held up by heavy machine gun fire. British reinforcements were sent but also so were fresh Turkish troops, and enemy aircraft successfully bombed the British logistical tail. In the final attack on 30 March, British troops penetrated the trenches around Amman but the defensive fire from the Citadel fortress made the captured positions untenable, and the British were forced to withdraw in appalling weather conditions back down into the Jordan Valley.

As General Allenby's force fought northwards, camel country was left behind and, in June 1918, the infantry battalions in the Imperial Camel Brigade were re-mounted on horses as mounted light infantry units. What happened to the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery is not clear, but it is probable that it was re-issued with pack mules for the guns and horse-drawn wagons for the ammunition and stores.

The final mention of the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery in the Official History is made during an account of the fierce fighting for Megiddo on 21 September 1918. The battery fired in close support of the 1st Royal Irish and the 38th Dogras, Indian Army, as those battalions drove back Turks holding positions 50 kilometres south of the Sea of Galilea. Megiddo was the final victory for General Allenby as he successfully concluded the Palestinian Campaign. As usual since its arrival in the theatre, the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery was up with the infantry and in the thick of the fighting.

Another Imperial Distinguished Conduct Medal was awarded to a British specialist with the battery for the Megiddo action:

- No. RGA/13318 Serjeant (Assistant in Gunnery) M J Muldowny: He has done invaluable work with the battery since its formation. He behaved with conspicuous coolness and gallantry during the operations from the 19th to the 22nd September, 1918, and on one occasion when the battery wagon lines came under considerable hostile shell fire he was conspicuous in superintending the removal of the animals.

And two further similar awards were made to Havildars, the respective actions could have occurred from the First Battle of Gaza onwards:

- No. 1178 Havildar Kishen Singh: For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When the officer of his section was wounded, he took his place, and though subsequently slightly wounded himself, performed the duties thoroughly and capably. By his cheerfulness and efficiency he was a fine example to the men of his section, and greatly contributed to the success of the action.

- Havildar Rur Singh. For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty, cheerfulness and never failing keenness throughout active operations. On one occasion when the battery was compelled to withdraw under heavy fire his coolness and total disregard of personal danger was worthy of the highest praise.

General Allenby's troops rode on to capture Damascus and Aleppo, but by 2 November 1918 the Turkish Government had accepted surrender terms and ceased fighting, as the surrender of Bulgaria had broken the communications link between Germany and Turkey.

On 5 November an announcement in the London Gazette stated:

The King has been pleased to approve of the Hong Kong-Singapore Battalion, Royal Garrison Artillery, being in future designated "Hong Kong-Singapore Royal Garrison Artillery."

The weary but triumphant Punjabi Gunners handed in their surplus Palestine equipment and were shipped back to a garrison routine with their batteries in Hong Kong and Singapore [26]. Every other soldier who had seen them in action, and especially their British, Australian and New Zealand colleagues in the Imperial Camel Corps, had regarded them with respect as professional gunners who fought their guns well forward and who put rounds on the target, whatever the personal risks.

Other Awards

In addition to the Distinguished Service Order and the nine Imperial Distinguished Service Medals already described, these other awards were made to battery members:

Military Cross

- Jemadar (Acting Subadar) Iman Din Khan: For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. On two occasions he displayed great coolness and courage under heavy fire. He has at all times set a fine example to his men.

- Jemadar (Acting Subadar) Alim Sher; Lieutenant (Acting Captain) Francis Lisney Skilton, Royal Garrison Artillery; Temporary Lieutenant Leonard Benjamin Tyler, Royal Garrison Artillery. (No citations published.)

Military Medal

- No 918 Gunner Ghulam Mohamed; No 1642 Gunner Nihal Singh; No 1624 Acting Naik Labh Singh; No 1422 Acting Naik Ghulam Hussain; No 1390 Naik Tika Khan.

Serbian Silver Medal for Bravery

- No 699 Gunner Karam Din.

Mentions in Despatches

- Major William Agnew Moore, Royal Garrison Artillery.

- No 15682 Company Quarter Master Serjeant H.H. Waldren, Royal Garrison Artillery.

- Jemadar (Acting Subadar) Iman Din Khan.

- No 1050 Havildar Fatteh Singh.

- No 699 Gunner (Acting Naik) Karam Din.

- No 722 Havildar Nawab Khan.

- No 1081 Havildar Piran Ditta.

- No 1255 Naik Rahmahtullah.

- No 1159 Havildar Rur Singh.

- No 1828 Havildar Sher Muhammed.

- No 1390 Naik Tika Khan.

Indian Distinguished Service Medal

As a British Imperial unit, members of the Hong Kong-Singapore Mountain Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery, were not eligible for awards specific to the Indian Army. Despite this fact two recipients of the Indian Distinguished Service Medal have been found, and the reasons for the award of this medal are a matter for conjecture:

- No 1623 RGA Gunner (Acting Naik) Jinder Singh and Senior Sub Assistant Surgeon Chaudri Maula Baksh.

Commemorations

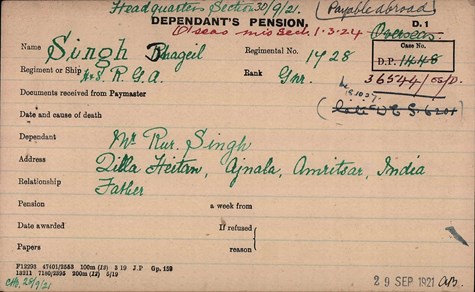

These ten names are inscribed on the Heliopolis (Port Tewfik) Memorial in Egypt:

No 1728 Gunner Bhagel Singh;

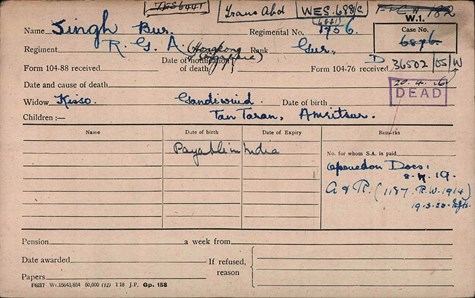

No 1756 Gunner Bur Singh;

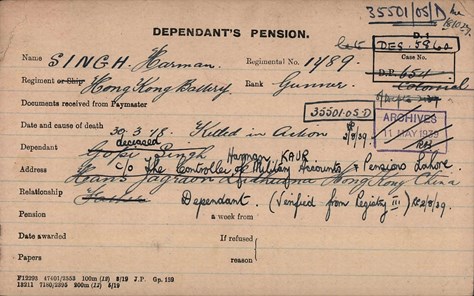

No 1789 Gunner Harnam Singh;

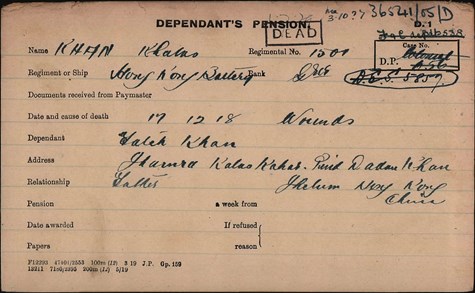

No 1501 Lance Naik Khalas Khan;

No 1740 Gunner Kishn Singh;

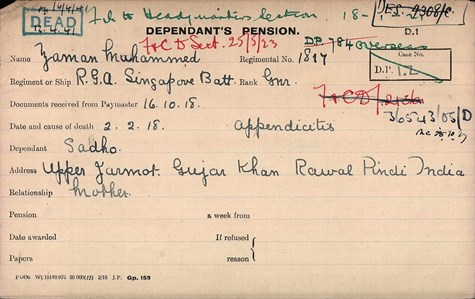

No 1817 Gunner Muhammad Zaman;

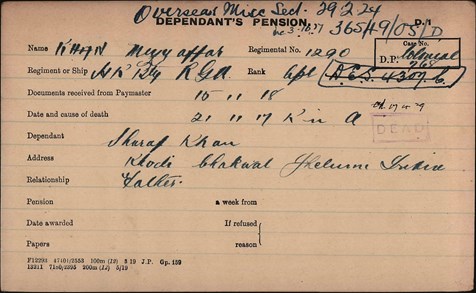

No 1290 Naik Muzaffar Khan;

No 1745 Gunner Saudagar Singh;

No 1705 Gunner Sultan Ahmad;

and Jemadar Wasawa Singh.

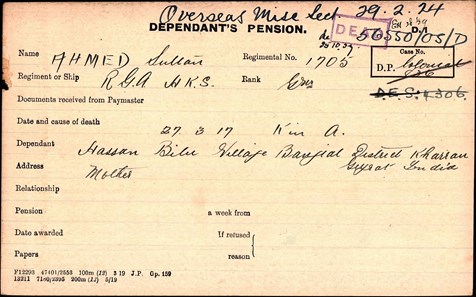

Pension Cards for all of these apart from the last named have been located in the WFA's Pension Record Archive (these images are at the end of this piece)

Two British Royal Garrison Artillery soldiers attached to the battery lie buried in Kantara War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt:

- No 69539 Saddler Donald Gillies and No. 9850 Gunner (Wheeler) V.A. Sykes.

- Second Lieutenant Ben Fletcher Chapman is buried in Gaza War Cemetery in Palestine.

The Imperial Camel Corps Memorial in London

On 22 July 1921 a memorial to the Imperial Camel Corps was unveiled on the Thames Embankment in London. On the front of the base is the sentiment:

To the Glorious and Immortal Memory of the Officers, N.C.O's and Men of the Imperial Camel Corps – British, Australian, New Zealand, Indian – who fell in action or died of wounds and disease in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine, 1916, 1917, 1918.

Above: Imperial Camel Corps Memorial in London

Article contributed by Harry Fecitt

Sources:

- de Rouen Forth, Nevill. A Fighting Colonel of Camel Corps. (Merlin Books Ltd, UK 1991).

- Farndale, General Sir Martin. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. The Forgotten Fronts and the Home Base, 1914-18. (The Royal Artillery Institution 1988).

- Graham, C.A.L. Brigadier General. The History of the Indian Mountain Artillery. (Gale & Polden Ltd, Aldershot, UK 1957 and downloadable here: https://archive.org/details/IndianMountainArtillery ).

- Lucas, Sir Charles. The Empire at War. (Oxford University Press 1926).

- MacMunn, Sir George and Falls, Captain Cyril. History of the Great War. Military Operations Egypt & Palestine, three volumes. (Imperial War Museum and The Battery Press 1996).

- Renfrew, Barry. Forgotten Regiments. Regular and Volunteer Units of the British Far East. (Terrier Press, Amersham, UK 1909).

- Robertson, John. With the Cameliers in Palestine. (A.H. & A.W. Reed, Dunedin, New Zealand, 1938, or Naval & Military Press reprint).

- Rollo, Denis. The Guns and Gunners of Hong Kong. (Gunners Roll of Hong Kong, 1991).

- Walker, R.W. Recipients of the Distinguished Conduct Medal 1914-1920. (Midland Medals, Birmingham, UK 1981).

- Wavell, Lieutenant General A.P. The Palestine Campaigns. (Constable, London 1941).

- London Gazette entries and Medal Index Cards.

[1] Paid for and directed from London.

[2] Known as the Boxer Rebellion or Uprising, or the Yihetuan Movement.

[3] The breech-loading 10-pounder mountain gun had been hurriedly introduced in 1903 after the failure of the 2.5-inch muzzle-loading mountain gun during the South Africa war. The new gun weighed 183 kilograms and the barrel was jointed for easy animal-packing. The caliber was 2.75-inches and the length of the assembled gun was 1.94 metres. Shrapnel ammunition and star shell were issued; the range was 5,486 metres but the gun sights were only engraved to 3840 metres. The recoil was controlled by a 'check rope' round the trail.

[4] For details of the initial Turkish attack on the Suez Canal refer to the article Turks Across the Canal in Durbar Volume 27, No. 1, Spring 2010.

[5] For further details of the Senussi invasion refer to the article The 15th Ludhiana Sikhs and the Senussi in Durbar Volume 27, No. 2, Summer 2010.

[6] German planes from El Arish attacked Port Said on 1st September 1916.

[7] The 1st, 3rd and 4th Battalions were composed of Australians and New Zealanders whilst the 2nd Battalion was recruited from British Yeomanry Regiments.

[8] The machine gunners came from the Scottish Horse, the Lanarkshire Yeomanry and the Ayrshire Yeomanry.

[9] Australian.

[10] For details of the VC award please refer to the article: http://www.kaiserscross.com/188001/487401.html

[11] There was one other medal for military distinguished conduct, the African Distinguished Conduct Medal that was awarded specifically to troops in the West African Frontier Force and the King's African Rifles.

[12] Comprised of the 1/1st of each of the Warwick, Gloucester and Worcester Yeomanry Regiments, the 16th Machine Gun Squadron and a Mounted Signal Troop. The Brigade Commander was Temporary Brigadier General E.A. Wiggin DSO.

[13] Besides the water shortage one British artillery battery had been withdrawn from the action as it had only 19 rounds remaining.

[14] As an example of casualty evacuation at that time in desert conditions the Australian & New Zealand Mounted Division allotted to each field ambulance: 10 pairs of litters, 15 pairs of cacolets (stretchers slung on each side of a camel), 12 sand carts, 12 cycle stretchers, and 6 sledges. All were animal-drawn except the cycle stretchers, and each field ambulance could concurrently evacuate 92 patients. But soon, when the desert sands had been left behind, motor ambulances would appear.

[15] The British seized 4 mountain guns, 4 machine guns, 578 rifles with considerable quantities of ammunition, 83 camels and 54 mules and horses.

[16] These men had belonged to the 31st Regiment of the Turkish 3rd Division.

[17] These 2.75-inch guns were 10-pounders without trunnions, recoiling through a cradle after firing to the extent allowed by the piston of a hydraulic buffer, and forced back to the firing position by the energy of springs compressed during the recoil.

[18] Charles Macpherson Dobell was of Canadian extraction and had been the British commander during the successful Allied invasion of German Kamerun in West Africa.

[19] Some batteries had to deploy some of their gun numbers on ammunition column duties.

[20] German pilots were flying Halberstadts against the British BE2's and Martinsydes.

[21] The first use of gas in this theatre.

[22] A few tanks, formerly used for training, were sent out from Britain and arrived in time for this action; it was found that if the traditional grease was not used on the tracks then the tanks could move through and on sand.

[23] 1.5 kilometres north of Beitunye and 2.5 kilometres from Ram Allah from which Turkish batteries were engaging them over open sights

[24] Footnote at page 200 of the second volume of the Official history.

[25] Sir H.S. Gullett.

[26] In 1915 the Hong Kong-Shanghai gunners serving in Singapore had helped in suppressing the mutiny of the 5th Light Infantry, Indian Army, in Singapore.