The Mobilisation of Britain’s Military Nurses 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Mobilisation of Britain’s Military Nurses 1914

The day after Britain entered the First World War, a ward sister at Charing Cross Hospital, Maud Hopton, signed a War Office contract agreeing to serve with the military nursing service 'at home or abroad' for a period of one year. Three days after this Maude found herself at Aldershot with 43 other nurses preparing to embark for France as part of No.2 General Hospital.

Above: Nurses outside No.13 Stationary Hospital, Boulogne, in the autumn of 1914. (Photo courtesy of Sheila Brownlee)

These women were a mixture of ‘regulars’, military nursing service reservists, and civilian nursing reservists like Maude, who only a few days before had been going about their normal work in civil hospitals or private homes with no experience whatsoever of military life or working in a war zone. Now they were kitted out and travelling overseas with the British Army as part of a military hospital.

The incredible story of the rapid mobilisation of these patriotic women is inspiring.

In July 1914, the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service had consisted of just 298 staff. Although this was the largest figure in the service’s history, these nurses were tasked with staffing more than 100 beds across military hospitals in the United Kingdom and overseas – including such postings as Malta, Gibraltar, Egypt, South Africa, and Hong Kong.

Above: An original British Red Cross cap badge

The outbreak of the war presented the service with an immediate challenge, and over the course of the next four years those challenges would keep on growing. The fact that it managed to meet them is down to the foresight of a reserve list that had been created nearly two decades prior to the war to embraced civilian staff – that, and the willingness to accept the help of semi-professionals and willing amateurs.

The military nursing service had set up its first reserve staff list in 1897 - one that included trained nurses who could be called upon by the War Office to boost its permanent staff as and when it was necessary. However, by the outbreak of the Great War there were just two hundred trained nurses on this list.

Thankfully, as part of a further drive in 1910, the matrons at some of the UK’s most prestigious civil hospitals had been asked to start their own lists of trained civilian nursing staff who would be willing to mobilise with the military if the need arose. In this way another 600 women were identified and put on the list.

Above: No.3 Southern General Hospital (TF), Oxford, outside the Examination Schools. (Photo courtesy of Judy Burge)

A third and crucial source of support came from the Territorial Force Nursing Service, which had been formed in 1909 and by the summer of 1914 could boast around 3,000 trained members ready to staff a proposed 23 Territorial Force General Hospitals.

As a result, on the eve of war there were around 4,000 fully trained nurses with some form of commitment to mobilise with the British Army. However, as civilians most had no obligation to do so until they signed an agreement with the War Office. Also, of the 298 serving members of the military nursing service, virtually none had any experience of active service work in wartime.

The Matron-in-Chief at the War Office, Ethel Becher, and her Principal Matron Maud McCarthy, set about organising their staff and dividing them into groups of between 40 and 50 to be attached to one of the British General Hospitals being mobilised to go with the British Expeditionary Force to France. Other reservists were sent to augment the staff of some of the UK’s large military hospitals.

Mobilisation for these nurses was extremely rapid, as the previously highlighted case of Maud Hopton exemplifies.

Reflecting the common mood at the start of the war, nurses initially clamoured to join the military nursing services, but there was not a bottomless pit of trained staff and the civil hospitals also had to be protected against losing too many nurses.

Above: VADs at No.74 General Hospital, Trouville. (Photo courtesy of Sue Light)

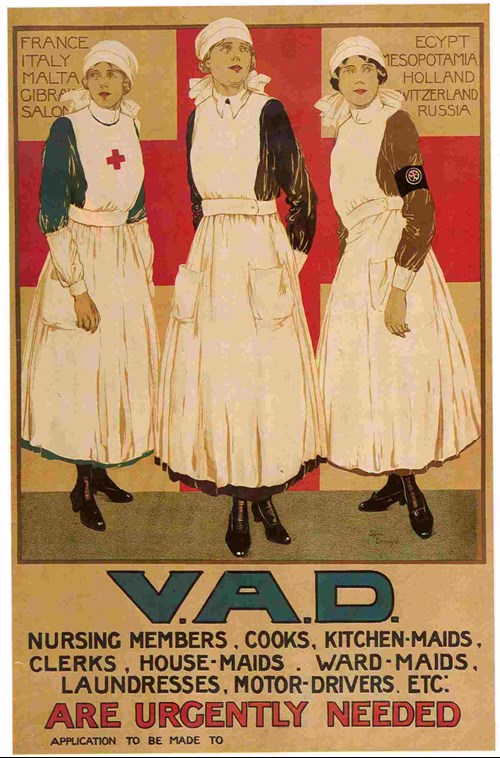

Above: A promotional poster encouraging young women to become VADs

The early levels of war casualties came as a shock, and by the start of 1915 it had become apparent that there would never be enough trained nurses to cope. The War Office realised that it would have to set aside reservations about employing untrained women – resulting in greater responsibility for semi-professional and volunteer staff that had been working in auxiliary hospitals under the control of the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John since the beginning of the war.

In addition to more than 22,000 trained nurses who served with the British military nursing services, it is estimated that around 120,000 other women served in some form of nursing capacity during the Great War. Thousands more nurses from across the UK, both trained and untrained, staffed wards in civil hospitals set aside for military personnel.

All of this developed from that initial small military nursing service of just 298 nurses. The patriotism and professionalism of these British Women in caring for the sick and wounded of the British and Commonwealth armies, as well as for German prisoners of war, is hard to quantify.

Original research Sue Light. Edited by Dr Martin Purdy.