The Search for Daniel Lightfoot

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Search for Daniel Lightfoot

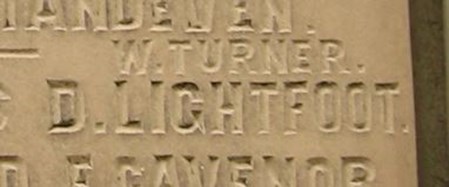

The search began with the war memorial on the wall of a former pub, the Dog & Partridge, 5 Hot Lane, Burslem, which was opposite my primary school and at the back of the brickworks where my father worked. I have known it virtually all my life. Only when my friend Mick Rowson and I decided to compile a Great War Roll of Honour for Burslem did I realise how complex and mysterious this memorial is, for all sorts of reasons. What follows is an account of one of the reasons: ‘D. Lightfoot’.

Above: The Dog & Partridge Shrine, Burslem

The memorial on which the name ‘D. Lightfoot’ appears is defined by the War Memorials Register as a ‘street shrine’. This was a designation given to temporary shrines that appeared during the war, though in some cases, perhaps this one, they later became permanent structures. The memorial has no date, but the reference to the war of ‘1914-1919’ places it after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. It is dedicated to the men of only two streets, Hot Lane and Elder Road. We have been reluctant to accept any identification of the 36 names on the memorial as correct unless we could find a definite connection with one or the other of these streets. The 36 names are divided by a short line: 23 names appear above the line and eleven below it. Two, obviously added at a later date, have been placed at either end of the line. The function of this line appears to be to separate the men who came from Hot Lane, whose names appear above the line, and those from Elder Road, whose names appear below it.

Above: Detail from The Dog & Partridge Shrine, showing 'D.Lightfoot'

‘D. Lightfoot’ was a mystery. He does not have an entry in Soldiers Died in the Great War, unlike all the other men named on the memorial. This might mean that he was not a soldier or he died after 11 November 1918 or (like my grandfather) he died after being discharged from the army. My grandfather does, however, have an entry in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Debt of Honour Register, which should also include sailors, marines and airman. There is no entry for a ‘D. Lightfoot’.

Did such a person exist or was ‘D. Lightfoot’ the stonemason’s equivalent of a typo? A search of the 1911 Census produced two possibles. The first was Daniel Thomas Lightfoot, 3 Arthur Street, Cobridge, aged 21, the son of Daniel and Amy Lightfoot. He was described as ‘a railway machine clerk’. Arthur Street is right on top of the ridge that separates Burslem from Hanley.

Arthur Street, Cobridge in the 1930s (photo: Alan Sutton © Ian Lawley & Tim Corum) www.thepotteries.org/potworks_wk/105.htm

Many people who lived there thought of themselves as living in Hanley not in Burslem (Hanley is actually closer). The 1901 Census revealed the family address as 1 Sutherland Street, Hanley. Without a connection in either census to Hot Lane or Elder Road we were reluctant to accept him as the name on the memorial. (This Daniel Lightfoot was almost certainly SS220580 Army Service Corps, which would fit with his clerking skills. He enlisted in the army on 5 December 1915 and was discharged as medically unfit on 18 October 1918, being awarded a Silver War Badge. He is almost certainly the same person who died on 13 August 1956 at 19 Oakville Avenue, Burslem. All the names on the Dog & Partridge memorial, except two, were infantrymen. None was in the Army Service Corps.)

The second was another Daniel Thomas Lightfoot, aged 27, and a collier (hewer) who at the time of the 1911 Census was described as a ‘Visitor’ at the home of his parents-in-law, Samuel and Emma Oakes, 12 Blake Street, Burslem.

Blake Street, Burslem (www.thepotteries.org/streets/burslem/blake_st/index.htm)

He had married Charlotte Oakes on 6 January 1908 and they had a son, Cyril, born on 25 April 1908. The 1901 Census showed this man as ‘Daniel Lightfoot’, aged 17, living at 14 Elder Road with his father James Lightfoot (1855-1926; collier), and his siblings, Ann, Mary, Catherine, John W. and Sarah. (1) His occupation was given as ‘brickyard labourer’. The 1891 Census showed the family living at 10 Hot Lane, this time also with their mother, Elizabeth (1851-99). Daniel Lightfoot was aged 7. It was strong evidence that this Daniel Lightfoot was the ‘D. Lightfoot’ on the Dog & Partridge memorial. It proved impossible, however, to find a probable date of death either for him or his wife.

The first major breakthrough came when we discovered an interview with Lightfoot in the Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel published on 22 January 1915.

Here it is:

BURSLEM SOLDIER’S AMAZING ADVENTURES

Liberates 13 English Prisoners in German Trenches

Four Times Buried in Debris

Private Daniel Lightfoot, of the 3rd Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, whose home is at 69, Brindley Street, Middleport, was invalided home a few days ago, after having been at the front since September.(2) In the course of a conversation with a "Sentinel” reporter, on Thursday afternoon, he told of some thrilling experiences. He has been captured by the enemy, and in escaping also enabled thirteen comrades to regain their liberty. But this was only one among a few exciting incidents he had to relate. On no fewer than four occasions has he been buried with debris after the bursting of German shells, without meeting with any actual injury. The effect of the artillery duels, he says, have been awful, and he agrees with many others who have been interviewed from time to time that the Germans are masters in artillery work. He holds their musketry firing in contempt, however, and thinks little of them as close fighters, except when they happen to have a big advantage in numbers.

A WARM ENCOUNTER

Private Lightfoot has been so much in the thick of it all the time that he has no memory for dates. He was one of twelve who were surrounded in a farmhouse, and after having had the satisfaction of bayoneting three of his antagonists and knocking over a fourth with the butt end of his rifle, he got clear to bring forward reinforcements. When he got back again with the much-needed help, four of the little band of twelve were missing. At another time, when the order to retire had been given, a shell burst close to and he was thrown into the trench which he and the others were just getting into. He fell heavily, and besides hurting his neck received internal injuries. It appears that it must have been considered all was over with him, for he was thrown out of the trench among the dead, and, from what he was told, the mistake was not found out until he was heard to be groaning, whereupon he was drawn back again and later taken to hospital.

CAPTURED BY THE ENEMY

This occurred just after his capture, which took place at Baileul [sic], in the North of France, sometime in the month of October. Lightfoot's story, in his own words, is as follows:- "I went out to fetch some water, and when I got to the pump I was surprised to hear a voice ordering me to put my hands up. I did so, and noticed I was in the company of some of the Germans. I was taken prisoner, and marched off to the German lines. Knowing I would be searched, I put my small pocketknife at the back of my puttee, in case I should want it, and it came in very handy. I was searched, and everything was taken away from me. When we got into the German trenches, they tied me up with transport rope. Afterwards, I saw thirteen other Englishmen there, bound up like I was. I was placed with my back to the side of the trench, and at once felt something sticking into my back. It was a rifle turned upside down, with the point of the bayonet in the ground. It must have fallen off the top of the trench. Seeing my opportunity, I looked round, and then began to saw at the bonds, against the bayonet, and succeeded in cutting my hands free. I was then able to get my knife and release my feet. There was a sergeant among the thirteen others, and I released him, and then between us we liberated all the men. It was night time, and the Germans were drunk, having pilfered some wine from a neighbouring village. We made away and got to the sentry and bowled him over.

SENTRY TAKEN PRISONER

I vaulted on to his back, and we were going to kill him when, speaking very good English, he cried out 'For God’s sake don't kill me; I will come with you’. He walked with us to our lines, about three-quarters of a mile away, where the others joined their regiments and I found mine." The rest of this hero’s narrative dealt with generalities. He spoke in the highest terms of the friendliness of the French and Belgian soldiers, and also of the wonderful order maintained among our troops, notwithstanding the hardships they are encountering. The weather has been very bad for a long time, he says, and once when he awoke after a short rest, he discovered small icicles hanging from the knees of his trousers. There was no doubt in his mind that the issue of rum was a great source of help to the soldiers, who were always in need of something of the kind under the conditions prevailing.

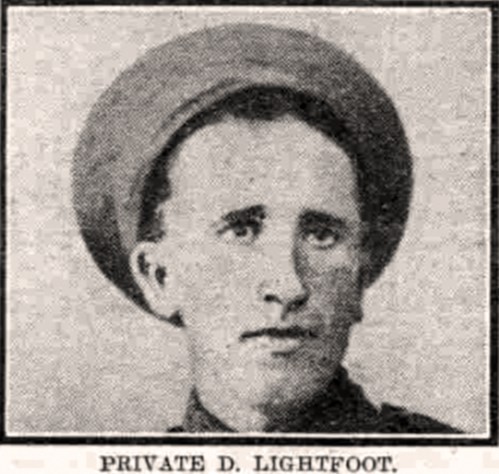

Private Lightfoot, who is a married man with one son, is a native of Burslem, and for many years he lived in Elder-road, Cobridge. He served in the Worcesters before the war broke out, and was called up as a reservist. (3)

HUSBAND OFFICIALLY REPORTED DEAD

The last few weeks have been a very anxious time for his wife who was officially informed of her husband’s death. By the very same post however she received a letter from him saying he was in hospital and improving slowly. Two days later an official intimation came telling her he was back to the firing line and then in a few days he arrived home invalided as a result of illness following upon his experience in the trenches. After his return there came another communication saying he was in hospital at Havre, whereas he was actually lying in bed at home when it was delivered. Mrs Lightfoot says she has sent numerous things to her husband which have not reached him and in particular she complains that a parcel of five undershirts she sent was returned to her after three months. Private Lightfoot who was wearing a woollen scarf at the time of the interview, informed our representative that the soldiers appreciate very much the comforts which are sent out to them. He came home on seven days’ leave, but this has been extended and though he is not looking so bad after his trying ordeals he does not expect to be quite fit for duty just at present. He is due to report himself to Worcester tomorrow week.

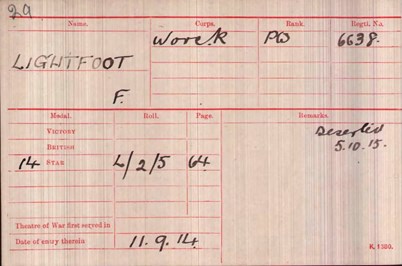

Case proved. This man was the ‘D. Lightfoot’ on the Dog & Partridge war memorial. However, as one door closes another hits you in the face. Daniel Lightfoot clearly was a soldier who had served abroad. He ought, therefore, to have a Medal Rolls Index Card, but he does not. We tried searching on ‘Lightfoot/Worcestershire Regiment’. The only hit was 6638 Private F. Lightfoot, 3rd Battalion Worcestershire Regiment, described as entering a theatre of war on 11 September 1914 (which fits with Daniel’s account). The card is also annotated ‘Deserted 5.10.15’.

Was ‘F. Lightfoot’ a mistake for ‘D Lightfoot’?(4) No one called ‘F. Lightfoot’ appears in Soldiers Died or the CWGC Debt of Honour Register either.

The 3rd Worcesters were in 3rd Division. This formation executed more British soldiers for capital crimes under the Army Act than any other. Five men from 3rd Worcesters were executed in July 1915 alone, all for desertion. None of them was called D. or F. Lightfoot. Nor were any of the men found guilty of a capital offence but given a lesser sentence. If Lightfoot had died while serving in the army he ought to have a death certificate, which should be recorded in ‘British Armed Forces and Overseas Deaths and Burials, 1796-2005’. No such death certificate exists.

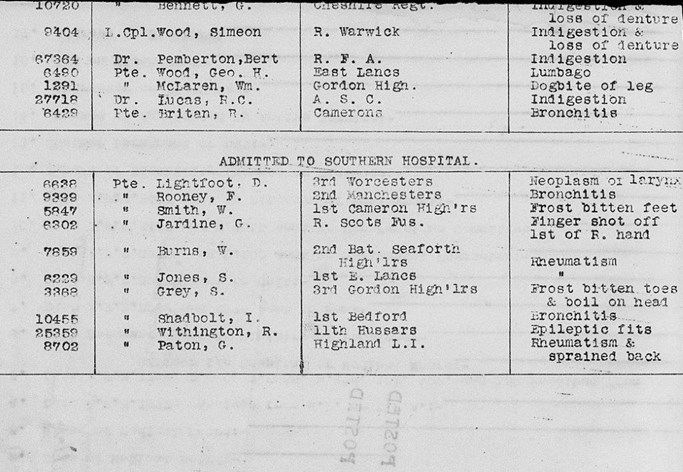

There the mystery remained for some time until Mick Rowson received an email from Findmypast, informing him that 584,000 ‘files’ relating to British soldiers in the First World War had been misplaced in the papers of other soldiers, but had now been extracted and indexed. Mick typed in ‘D. Lightfoot’ and up he came! Specifically, what came up was a fragment of an undated list showing ten admissions to ‘the Southern Hospital’. Top of the list was ‘Private Lightfoot, D., 3rd Worcesters’.

Above: The document located on Findmypast.

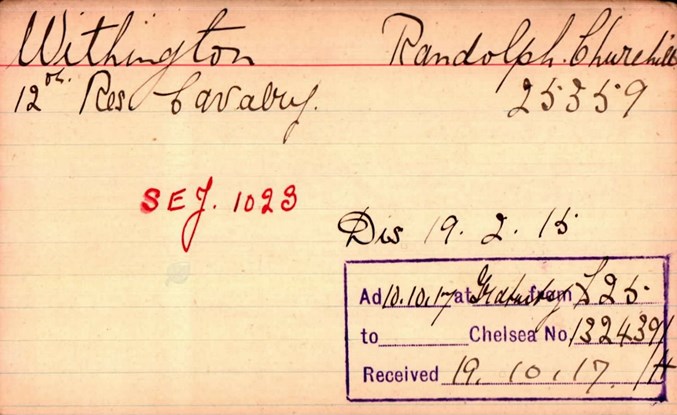

The list included his service number – 6638, the same as that of Private F. Lightfoot, who had deserted on 5 October 1915! I checked to see if any of the other soldiers who were apparently admitted at the same time as Lightfoot had files. One did: the wonderfully-named Private Randolph Churchill Withington (11th Hussars).

Above: The Pension Record Card for Randolph Churchill Withington (The Western Front Association collection on Fold3 by Ancestry)

Withington’s pension file has survived. This shows that he was admitted to the Southern Hospital, Liverpool, on 18 December 1914 and was discharged from the army in February 1915 (epileptic fits).(5)

This rather suggests that Lightfoot was admitted at the same time and had been discharged by the time of his interview with the Weekly Sentinel. As he claimed to be returning to his regiment the following week it also suggests that the diagnosis, pre-admission, of ‘neoplasm of the larynx’, was incorrect.(6)

Mick then found Lightfoot’s Militia attestation papers from 1901. Why we had not found them before is a mystery, too. Lightfoot gave his age as 17 years 4 months, his address as 14 Elder Road and his occupation as labourer. He enlisted in the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the North Staffordshire Regiment at Whittington Barracks, Lichfield, on 29 April 1901 and transferred to the Worcestershire Regiment on 3 January 1902, his eighteenth birthday.

Above: Whittington Barracks, Lichfield

This also presented a problem. Most soldiers served a 12 year engagement, involving a period with the colours and a period on the Reserve, usually 7/5. Daniel Lightfoot’s obligation to return in the event of a general mobilisation should therefore have expired in January 1914.

There remains the possibility that he extended his Reserve obligation and joined the Section D Reserve.(7) After all, this was money for old rope. Britain was not going to be involved in a major war requiring general mobilisation any time soon, was it? There is another problem. If he joined on a 7/5 engagement, he should have been with the colours until January 1909, but he was married in January 1908 and living and working in the Potteries as a collier. A 3/9 term of engagement was introduced in May 1902, but does not appear to have been applied retrospectively. A mystery within a mystery.

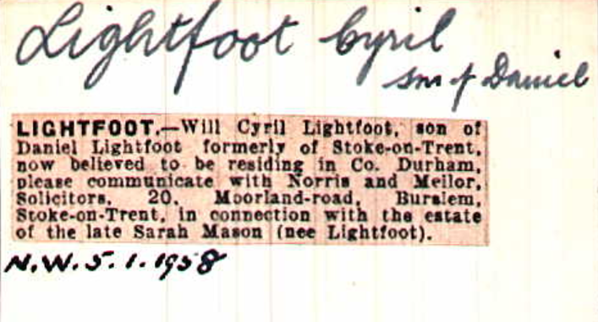

One of my principles is ‘when stuck, redefine the problem’. At this point I changed the line of enquiry from Daniel to his wife and son. Cyril provided the breakthrough. I found a reference to a Cyril Lightfoot in Andrews Newspaper Index Cards 1790-1976. This consisted of a cutting from the News of the World, dated 5 January 1958: ‘Will Cyril Lightfoot, son of Daniel Lightfoot formerly of Stoke-on-Trent, now believed to be residing in Co. Durham, please communicate with Norris & Mellor, Solicitors, 20 Moorland Road, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, in connection with the estate of the late Sarah Mason (née Lightfoot)’.(8)

I checked for Cyril Lightfoots marrying/dying in the Durham area: to discover a marriage at Stockton-on-Tees between Cyril Lightfoot and Edith Ann Kiddle in the fourth quarter of 1934. Cyril Lightfoot died in Durham in the fourth quarter of 1966, aged 58.Having pinned Cyril to the north-east, I began to look for his mother there, too, checking marriages, to discover that a Charlotte Lightfoot married Thomas Edward Dodsworth in Stockton-on-Tees on 25 March 1922. He is described as a ‘joiner at a shipyard’ and as a ‘widower’; she is described as a ‘widow’. Her father’s name is stated as ‘Samuel Oakes’. He was 51; she was 34. Thomas Dodsworth was born in Mexborough in 1871. In the 1911 Census he is described as a ‘stage carpenter’. It is also seemed clear that Charlotte had moved to the north-east with her parents: Samuel Oakes died in Stockton in January 1928; his wife Emma (née Ray) also died there in December 1925. Charlotte Dodsworth (formerly Lightfoot, née Oakes) died in Durham in March 1953, aged 66. Thomas Dodsworth died in Stockton in June 1938.

Charlotte Lightfoot had five children with Thomas Dodsworth. Two of these children were born before their marriage. Her wedding lines describe her as a ‘widow’. Question: why did they not marry earlier? (9) Possible answer: because she had to wait seven years to have Daniel Lightfoot declared dead. A solicitor friend kindly offered to find out about seeking a declaration of death in 1922. The information, if correct, was disappointing. It looked like there would be no paper trail. My friend wrote ‘I have had a response from the Diocesan Registrar. He confirms that the standard of proof at the time in such cases would have been “Balance of Probability” not “Beyond Reasonable Doubt”. In those less bureaucratic times a widow simply stating that her husband was seven years dead would have been regarded as sufficient by both civil and religious marriage officiators and no formal paperwork would have been required.’

It seemed that we had taken this as far as we could go and set it aside on what Joe Devereux, chronicler of the Worcesters, calls the ‘too difficult pile’. Until recently.

The search resumed after Andrea Hetherington’s excellent Western Front Association webinar about 'Deserters on the Home Front' broadcast on Monday, 15 March 2021. This inspired me to look again at the Mystery of Daniel Lightfoot. Things moved remarkably quickly.

Andy Johnson discovered that Lightfoot’s adventures had been reported in the Daily Mirror, the Newcastle Chronicle and the Sunderland Daily Echo on the same date, 16 January 1915, a week before the Sentinel interview was published. It became apparent from these reports that 69 Brindley Street, Middleport, was not Daniel’s home and that his wife had not moved to the north-east after the war. They had both moved there before the war. Daniel was a porter on the North-Eastern Railway [NER] at Coxhoe Bridge station and they lived at West Cornforth, Co. Durham.

Above: Coxhoe Bridge Station © Photograph Library Beamish Museum

It is not known at what point the Lightfoots moved to the north-east or why. The earliest Daniel appears in the NER staff records is April 1913.(10) There is no indication of railway employment before that date.

His stated occupation in 1908 and again in 1911 was ‘collier’. There was an important coal mine at West Cornforth, Thrislington Colliery. Perhaps that originally drew him. Daniel had obviously settled in the area. He was Scout Master in West Cornforth and a well-known local figure.

Above: West Cornforth War Memorial

At this point, you could positively hear the plot thickening! I had always been reluctant to identify Daniel Lightfoot as a deserter solely on the basis of a statement on a Medal Roll that could not even get his initial right. I brought to mind an interesting article in the Birmingham Post on 12 May 2016 about the successful campaign by Nikki Medlicott, from Walsall, to get the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to accept that her great uncle, Private Thomas Gravenor, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, was not a deserter but had been killed in action on 29 September 1916 in Salonika. Perhaps Daniel’s reputation had been similarly traduced in the fragmentary historical record. We soon heard another sound, however. It was the noise of a theory collapsing.

I found Daniel Lightfoot’s name in the ‘Register of Charges Home and Abroad’. He was court martialled for desertion on 25 June 1915 in Worcester and sentenced to 70 days’ detention. His release would have been sometime at the beginning of September 1915. The date of desertion on ‘F. Lightfoot’s’ MIC was 5 October 1915, which suggests that he deserted again as soon as he was out of detention. I am grateful to Andrea Hetherington and Dr Alison Hine for clarifying the procedure that would have been followed.

King’s Regulations (1914), para. 514, stated ‘When there is good ground for supposing an absentee to have deserted, the report [to the Police Gazette for publication] should be rendered within 24 hours after his absence has been discovered, but in no case should it be delayed beyond five days. Up to 21 days the man should not be returned as a deserter, unless there is ground for supposing that he has deserted. After 21 days, every absentee without leave should, pending investigation, be considered as a deserter.’(11)

We will soon have Andrea Hetherington’s book on Home Front deserters, but in writing this article I have become aware of the inadequacy of the literature about desertion on the war fronts, which is focused almost entirely on deserters who were caught, tried, convicted and executed.

How many men successfully deserted in France and Belgium and were never apprehended? Even a cursory examination of Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914-1920 shows that it enumerates only those deserters who were actually tried for the offence, not how many actually deserted. As Andrea Hetherington points out, ‘the court martial figures don’t match the desertion figures or the figures calculated by reference to the Police Gazette. Summary disposal was applied in what must have been many thousands of cases, meaning men never had to face a court martial. In terms of those who got away with it, in that they were never even apprehended, again it must be quite a large number - the net loss to the Army from desertion over the war years [1914-20] was 82,232.’ (12)

The balance of probability suggests that Daniel Lightfoot did desert and remained free. It would have been much easier to achieve this had he deserted at home. In an era that lacked identity documents it was, perhaps, not that difficult to keep out of the clutches of the military and the police, though perhaps a bit more difficult after the onset of conscription. But Daniel Lightfoot’s success in remaining free would necessarily have to have been built on the abandonment of his family. It is this, rather than his desertion per se, that shocks at this distance and from our perspective.

We need to look at this mystery from Charlotte’s point of view, too. Her separation allowance and the allowance for Cyril would have been stopped immediately Daniel’s desertion became a ‘fact’. This would have placed her in grave difficulty not only financially but also socially. The first thing the police would do in search of deserters was to make enquiries of the man’s family and neighbours. It would have been very difficult to keep this news quiet in small, close-knit working-class communities. Perhaps it was at this point that Charlotte’s mother and father moved to the north-east to provide moral and financial support to their daughter and grandson. Her first child with Thomas Dodsworth was born on 8 June 1918 and would have been conceived in September 1917, almost two years after Daniel was posted as a deserter. There is no evidence that Charlotte had been informed of her husband’s death and she did not receive a war widow’s pension. She must surely have been aware of his desertion. Did she know he was definitely not coming back before she took the step of conceiving a child with another man?

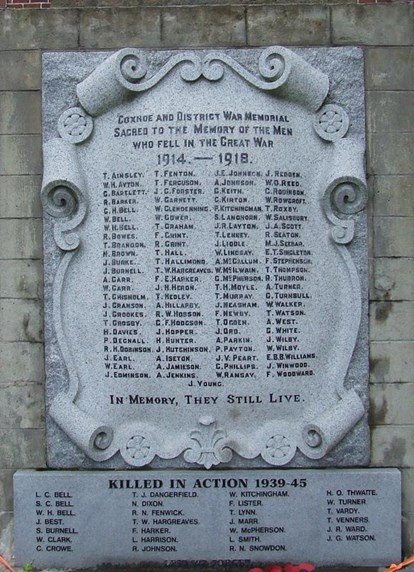

We come, at last, to where we started - the Dog & Partridge memorial. Someone must have been responsible for Daniel Lightfoot’s name being there. He still had family in the area, including his father and the sister at whose house he had given the newspaper interview. The fact that he gave the interview there and that Sarah remembered Daniel’s son in her will suggests a close bond. Whoever was responsible for the inclusion of his name must surely have believed him to be dead. However, Daniel Lightfoot’s name does not appear on the Coxhoe and District War Memorial or the war memorial of St Mary’s Church, Coxhoe, or the West Carnforth war memorial, places where he worked, from where he went off to war and where his wife and son lived.(12) These omissions are surely significant.

Coxhoe and District War Memorial

Above: St Mary’s Church, Coxhoe War Memorial

J.M. Bourne

Mick Rowson

[We wish to acknowledge the help of Nick Baker, Ronald Cullen, Joe Devereux, Su Handford, Andrea Hetherington, Andy Johnson and Dr Alison Hine in researching this article, none of whom is responsible for the views expressed.]

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of the Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.

Notes

(1). Daniel’s brother, John William, is certainly the ‘J.T. Lightfoot’ on the Dog & Partridge memorial. He suffered a gunshot wound to his left thigh on 4 March 1918 while serving with the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. He was invalided back to Britain but died of his wounds (and of pneumonia) in the Norfolk War (General) Hospital, Blofield, on 17 August, aged 38. He is buried in Burslem Cemetery under a CWGC headstone. The personal inscription reads ‘He Did His Best’.

(2). The description of 69 Brindley Street as Lightfoot’s ‘home’ proved to be misleading and we failed to draw the appropriate inference even when we discovered it was actually the home of his sister, Sarah Sanders.

(3). Stoke-on-Trent’s local newspaper, the Sentinel, rehashed this story on 16 November 2015 with an illustrated double-page spread. The author concluded (correctly) ‘There are no soldiers called Daniel Lightfoot listed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as having died during the Great War’, adding ‘so it appears he survived the conflict and returned to his home, to his wife Charlotte, and young son Cyril’. As it turned out, this conclusion was incorrect.

(4). The handwritten Medal Rolls Index Cards took their information from the typed Medal Rolls. ‘F’ is next to ‘D’ on a typewriter, so it would be an easy mistake to make. Lightfoot seemed to attract clerical errors. The handwritten ledger of his admission to No. 2 Hospital, Havre, lists him as ‘Lightfoot, ‘F’ or ‘J’ or ‘I’ or ‘T’, but definitely not ‘D’, although the unit and service number are the same, 3rd Worcesters, 6638.

(5). The Royal Southern Hospital, Caryl Street, Liverpool, was opened in 1842 and closed in 1978.

(6). Lightfoot was admitted to No. 2 Hospital at Havre on 8 December 1914. The diagnosis was ‘exopthalmic goitre’. ‘Exopthalmic’ means bulging eyes and goitre implies that this was due to an enlarged thyroid. Lightfoot was evacuated to Britain on the Hospital Ship Asturias on 15 December 1914. We owe this information to Nick Baker. The Royal Southern Hospital doctors’ initial diagnosis was a ‘neoplasm’ or tumour on the larynx. One interpretation of the diagnosis would be ‘laryngeal cancer’. This was clearly not the case. It seems probable that Lightfoot had suffered a physical trauma to his neck/throat that had produced swelling and might explain why he was wearing a scarf during his interview with the Sentinel.

(7). The typical terms of service in the pre-Great War period were seven years with the colours and five years with the Section B Reserve. Soldiers who had completed their time in the Section B Reserve could opt to extend for another four years by joining Section D. They received pay of 3s 6d per week. Soldiers in the Section B and D Reserve could only be recalled in the event of a general mobilisation.

(8). Sarah Lightfoot, Daniel’s youngest sibling, married Ernest Sanders, a potter’s turner, in 1909; he died in 1926. She married James Mason in 1928. Mrs Mason lived at 6 Garlick Street, Burslem. She died in June 1957. Her estate was worth £2,586 3s 4d.

(9). Thomas Dodsworth’s first wife died in 1902.

(10). We wish to thank Alison Grange, Collections & Learning Assistant, Head of Steam - Darlington Railway Museum, for this information.

(11). The names ‘D. Lightfoot’ and ‘F. Lightfoot’, however, have not been found in on line editions of the Police Gazette, though access to this important source is somewhat patchy and problematic.

(12). Some men who deserted may have re-enlisted under another name, as is being revealed by the WFA’s ‘Project Alias’, but not 82,000!

(13). The war memorial of Stockton-on-Tees, where Sarah lived with Thomas Dodsworth, is a cenotaph without names.