The Soldier who never was: An example of a Change of Name in the Late-Victorian Army

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Soldier who never was: An example of a Change of Name in the Late-Victorian Army

Every student who undertakes research into the personal histories of soldiers who served in the Victorian Army will have come across a name which turns out to be an enigma. Assuming the integrity of the available research, for example, an entry on the medal roll, the researcher has to conclude that something else has caused the difficulty in establishing even the most basic data about the subject, eg birth, marriage, death, and an appearance in the available censuses. In the end the student will tire of the effort and expense involved in undertaking the required research, and move on to other names which offer a more rewarding experience, although for the student of a particular regiment and campaign, like me, admitting defeat in this way is always frustrating. In the end this student will come back to the research and worry at it until, hopefully, something currently hidden can be discovered to open up a new research path. I have two examples of this sort of experience, where the initial research seemed to lead nowhere.

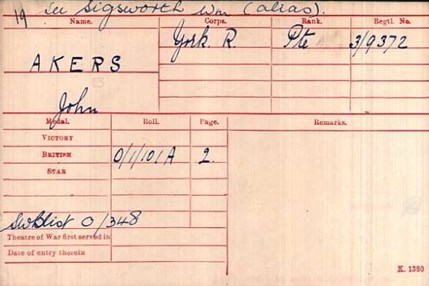

The first name is JOHN AKERS, 2/Yorkshire Regiment, who took part in the Tirah campaign in 1897-98. His medal for that campaign is itself numismatically interesting, as the naming is in the ‘wrong’ style for this medal. It should have been engraved in what is usually called the ‘running script’ typical of the Calcutta mint; this one was impressed in the style of the Queen’s South Africa Medal. Clearly it was a replacement, and the medal roll (WO 100/87 f 11) seemed to endorse this, as the remarks state: ‘Rep 31132/BM 30/10/34’, which I interpreted as a replacement having been issued on 30 October 1934. By chance I discovered some time after I bought the medal in July 1994 that the original is in the collection of the Green Howards Regimental Museum.

Initially all attempts to find this man in the usual sources failed. There was no record of service for him in the WO 97 series of documents at the Public Record Office (as it was then). There was no match in the General Register Office (GRO) records for any birth or death that could be related to him. There was no person of this name who fitted the known details in the censuses for 1871, or 1881, years when I believed a soldier serving in 1897 should have been recorded. Even though the medal roll indicated that he was almost certainly alive in 1934, I contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (in those days one had to write or telephone); there were eleven death records for a man with the surname AKERS and initial J, with possibly another forename. Of these, only two were positively John Akers (ie without a middle name), but one was an Australian, and the other turned out to be a man who did not fit in any other way with what I already knew about John Akers at that time.

I decided to expand my research by looking for a marriage record, albeit without much hope of success, and so I was very surprised to find one: a marriage in the September quarter of 1906. The certificate recorded that John Akers married Kate Ann Simpson, a twenty-nine year old domestic servant of Kirby Sigston, Northallerton, at the Register Office, Northallerton, on 5 July 1906; he was described as a thirty-nine year old farm labourer of Winton, Northallerton. He stated that his father was also called John Akers. Even with this additional data which located John Akers in a particular geographical area and timeframe I could not find any reliable evidence for the existence of this man. Having spent so much time researching him I was obviously disappointed, but I reached a stage where I believed that I would be throwing good money after bad if I continued to pursue this trail any more, and so reluctantly I mentally shelved him, and moved on to more rewarding research. Even though the Great War Medal Index Cards were available at the time I had given up on John Akers as a possible participant in the Great War, if only because of his age: on his wedding certificate he was recorded as thirty-nine in 1906. He could well have been too old or infirm for service in 1916 when conscription was introduced.

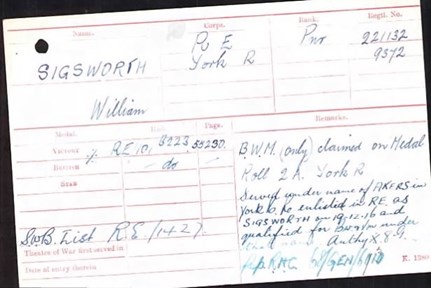

However, it was through the Great War records that I eventually found him in a very unexpected way. More recently, when I decided that I would make a particular study of the men of 2/Yorkshire Regiment who took part in the Tirah campaign, I began to look again at old research where I believed there was more to do, and decided that John Akers was a candidate for this process. As the vast amount of data that used to be held only at The National Archives, Kew, was then available digitally through the medium of Ancestry and FindMyPast, I started where I had left off: looking for any Great War service. By that time I had already found the details of several Tirah campaign veterans who had re-enlisted into the Special Reserve battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment in 1914, and so decided to go down that path using the Medal Index Cards (MIC) now available through Ancestry. However, when I found his MIC, I was both surprised and exasperated. The information that I wanted was there, and had been for many years, if only I had thought to research the MICs when I was still hunting for him. His MIC recorded not only that 3/9372 John Akers, York R, was awarded the British War Medal and a Silver War Badge, but that there was another name cross-referenced with his: ’William Sigsworth (alias’).

This was the beginning of a fascinating, if confusing, search through the records of William Sigsworth. He was born 20 July 1865 at Thornton-le-Moor, the son of Mary Sigsworth; no father was recorded on the certificate. In 1871 he was living with his grandmother Rachael Sigsworth at Thornton le Moor, a village midway between Northallerton and Thirsk; he was age five, born Thornton le Moor, Yorkshire. In 1881 he was a farm servant living in Theakston, near Bedale, with the family of David Waind, an employer; he was age sixteen, born Thornton le Moor. So far so good, until he attested for the Royal Artillery at Redcar 28 June 1884, number 43329. His service record (WO 97/3855) stated that his name was William Sigsworth, that he was age nineteen years one month, that he was a labourer, and that he was born in Thirsk. He was five feet seven and a quarter inches tall, weighed 144 pounds, with a fresh complexion, hazel eyes, and light brown hair. The fact that he was taller and heavier than the average recruit of this time was almost certainly a reflection of the life he had led. Recruits from country areas at this period were usually physically better built than those from the towns, but Sigsworth appeared to be egregious at a weight of ten stone four pounds, or sixty-five kilos.

Unfortunately for the Army William Sigsworth was not a very good soldier. It is a great shame that the service record did not provide details of his misdoings, but recorded only his punishments. He was awaiting trial 21 June 1886, was tried and imprisoned 23 June. He was released 7 July (fourteen days later), but was awaiting trial again 14 August 1886, was tried and imprisoned 28 August 1886 and released 4 September 1886. He was awaiting trial 20 December 1886, tried and imprisoned 15 February 1887. He was released 15 May 1887, which sounds like a longer sentence. He was transferred to the Army Reserve 16 December 1891.

The most usual offence committed by Victorian soldiers was drunkenness, but there was more on Sigsworth’s service record which painted a different picture. One note read: ‘Confessed to have been discharged with Ignominy from Royal Marine Light Infantry on 23 February 1883 in which he served as No 495 Private William Sigsworth.’ The next entry on his record shows that he ‘improperly enlisted into 3rd Hussars as No 3155 Private J Sigsworth on 22 January 1892’. In 3rd Hussars he was awaiting trial 26 July 1892, was tried and convicted of ‘I[mproprer] E[nlistment’] 23 August 1892. He was imprisoned for six months. He then committed yet another offence: escaping while a prisoner. He was tried and imprisoned for eight calendar months (one calendar month remitted) on 3 September 1892. He was discharged with ignominy on 30 September 1892. His address on discharge was ‘Post Office, Thirsk’. It appears that William Sigsworth was a serial enlister and deserter, for what reason was not spelled out, but presumably it was for the bounty payable. He might have got away with more had he changed his name each time, but he failed to do so and was probably detected because of it.

However, something must have changed in 1893, when he enlisted for the Yorkshire Regiment under the name of ‘John Akers’. This was perhaps not as surprising as it might appear, as on his original attestation under the name Sigsworth he gave his next-of-kin’s name as his father, James Acres (this is how it was spelled in that document, and the Akers form might be a corruption). Did Sigsworth make up this name, or did his mother tell him that James Acres was indeed his father, although it was impossible to prove?

There is not a great deal to be found to describe William Sigsworth/’John Akers’s’ service in the Yorkshire Regiment. There are a few references in the Green Howards Gazette: his service number indicates an enlistment in October 1893, as a recruit from the Depot he joined B Company of 1/Yorkshire Regiment at Jersey 27 February 1894, and he was included in a draft of 106 NCOs and men from 1/Yorkshire Regiment under Lieutenant Wilfred Harry Dent which sailed from Southampton 5 February 1895 on the Transport Britannia to join 2nd Battalion in India. Because of the change of name from Sigsworth to Akers, which was discovered by the authorities before the records were permanently filed, there is no separate record available for a soldier called ‘John Akers’.

Above: India Medal two clasps awarded to 'John Akers'

The next record that could be attributed to the name ‘John Akers’ is his wedding: he married Kate Ann Simpson in Northallerton (as already described above). The 1911 census relating to this family is intriguing. First, ‘John Akers’ was describing himself as William Sigsworth, so clearly he had told his wife about his previous life. Second, there were four children: Edward, ten years old, Robert, seven, John, three, and James, two. What is surprising is that the first two have the surname Simpson and the last two have the surname Sigsworth. Remembering that ‘John’ and Kate married in 1906, it is clear that Kate brought two sons into the marriage with her. The chances are that the first two were not the result of a union between ‘John’ and Kate, as ‘John’ was in India when son Edward was born, and Robert was born before ‘John’ and Kate were married, and probably before they had even met. The family was living in three rooms at Borrowby, Thirsk; William was described as a forty-six year old farm labourer, born Thornton le Moor. This document is confusing in the light of what was found later.

After this there is nothing officially about John Akers until he enlisted for the Yorkshire Regiment Special Reserve on 28 November 1914 with the number 3/9372. Presumably he wanted to be able to claim his past service in the Yorkshire Regiment under the name of ‘John Akers’, as he seems to have left William Sigsworth behind again after 1911. A document (Army Form B200A, ‘Statement of the services of No 3/9372 Sigsworth W’) recorded that ‘John Akers’ attested at the Yorkshire Regiment Depot, Richmond, age forty-seven, for the duration of the war, on 28 November 1914.

Above: Market Square, Richmond, North Yorkshire, the Depot of the Yorkshire Regiment. Trinity Church on the left is now the Green Howards Museum

He was posted to 3/Yorkshire Regiment 18 January 1915, to 1/Garrison Battalion 28 November 1915; to India 24 December 1915; he was attached to the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry 13 June 1916, and discharged no longer physically fit for the service 16 July 1916. His next of kin was recorded as Mrs Kate A Akers (wife), Long Street, Easingwold. As a result of this discharge he was awarded a Silver War Badge in the name of ‘John Akers’, on 20 January 1917.

According to his MIC he was posted to 1/Yorkshire Regiment in India, and qualified for the British War Medal as a result.

However, he must have returned before the end of 1916 because the next phase of his story began on 19 December 1916 when Pioneer 221132 William Sigsworth enlisted for the Royal Engineers in York and was posted to 310 Road Construction Company in France. Clearly this confusion of names brought about an enquiry when his wife applied for a separation allowance. A document dated 27 March 1917, signed by Second Lieutenant A F Hobbs, related to Pioneer William Sigsworth: ‘I have interviewed him & have obtained as much information as is possible. It would appear that Sigsworth enlisted in the Yorkshire Regiment round about the year 1894 under the name of Akers & under this name he was married, on a date not remembered by him, at Northallerton & 3 children were born under this name. At this time he was compelled to change to his own name & the subsequent children bear the name of Sigsworth…The matter has already been gone into whilst he was in the Yorkshire Regt & the records were seen by the authorities at that time. The delay in this correspondence is due to Sigsworth being in hospital until today.’ He was obviously not a man to remember his wedding anniversary!

He was discharged from the Royal Engineers 5 January 1918, unfit for military service, and received another Silver War Badge for this discharge in the name of William Sigsworth. Clearly either his past habitual attestation could not be overcome, or he could not stand the six children at home, because three months later he attested for the Army Service Corps at York on 18 April 1918, and was posted to a Motor Transport Company at Isleworth. What is strange at this point is that he correctly admitted to having been discharged from the Royal Engineers; perhaps the ASC was desperate for recruits and was only too pleased to receive an application from an old soldier. The attestation document recorded his age as forty-nine years six months, and described him as a horse driver. He was five feet seven and three quarter inches tall. There were six children listed for whom he had responsibility, according to a document he signed in December 1916 stating that he was called Akers when he married and when his children were born. The two boys with the Simpson surname in 1911 retained that name. His youngest child, born 8 January 1916, was given the forenames Ernest Kitchener.

On 13 August 1918 he voluntarily transferred to the Horse Transport Branch. On 24 March 1919 he volunteered for one year at St Albans, so he was still unhappy about going home. On 16 August 1919 he was posted from 309 Company to 531 Company, at York. On 21 February 1920 he was dispersed from 531 (HT) Company ‘in consequence of Demobilisation’. His Protection Certificate gave his RASC number as 423667. He received his British War and Victory Medals on 14 February 1923; he signed for them in the name of Sigsworth.

What happened to him after that is difficult to trace. His wife Kate died on 26 December 1935 at Easingwold, and her death was registered under the name Akers; she was described as the wife of William Akers, a general labourer, the first time that this rendering of his name had occurred in an official document. Finding the date of death for William Sigsworth/’John Akers’ has proved very difficult, as there is no clue as to whether his death was registered under the name Sigsworth or ‘Akers’. He does not appear on the 1939 Register under either name; logically he must have died after the death his wife as he was described as her husband, not her ‘late’ husband, and before the 1939 Register was compiled, which narrows down the time period of his death. During that period there were only two deaths registered that on age grounds could be our man, but further research has shown that neither of those were ‘my’ man. What happened to William Sigsworth is therefore uncertain, and open to speculation.

Name changes are anathema for researchers of all kinds, particularly family historians. I have come across this many times in my research of these late-Victorian soldiers, and it is often allied with the early death of both parents, the effect of which was that children were being brought up by other family members with different surnames. Often the child(ren) chose to revert to their original surname in later life, particularly on marriage. It is quite clear that William Sigsworth did what he did in order to claim the enlistment bounty, but did not change his name with each fraudulent enlistment; why he changed his name and his behaviour in 1893 when he attested for the Yorkshire Regiment is impossible to discover. It appears that he wanted ‘John Akers’ to be a new start in life for him.

Article contributed by John Sly