Two men with five names: The Curious Case of Cornelius Costello

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Two men with five names: The Curious Case of Cornelius Costello

The image of the headstone below, which is in Dover (St James's) Cemetery, is perhaps not terribly unusual. It names an unknown sailor of HMS Glatton and another sailor - Cornelius Costello who 'served as' a stoker on HMS Glatton. The headstone is somewhat odd in that it does not give the name that Costello served under - this is revealed by his entry with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which states he served as Robert Snowball. For a variety of reasons, other than the unusual surname, this is not a unique scenario as many men used an alias.

Above: The gravestone of Cornelius Costello

Above: Dover (St James's) Cemetery

However, the story behind this seemingly fairly standard headstone is complicated and intriguing....

HMS Glatton

Towards the end of the war, an explosion occurred on a Royal Navy monitor in Dover Harbour which, had quick action not been taken, could have led to the devastation of the town on a very large scale

P/S Bjørgvin was the name given to a large monitor that had been ordered by the Norwegian Navy before the beginning of the Great War. In 1914 the ship, which was under construction, was requisitioned by the Royal Navy (with full compensation paid to the Norwegians) and renamed HMS Glatton.

Above: HMS Glatton

After undergoing modifications she was finally commissioned on 31 August 1918 and sailed for Dover.

The hull of the monitor HMS Glatton in dry dock, showing the anti-torpedo bulge.

At 6.15pm on 16 September, whilst in Dover Harbour, a small explosion ignited cordite stored in one of the Glatton's magazines. Flames shot upwards and outwards and started to spread aft. The ship's captain ordered the magazines to be flooded but the crew were unable to do this to all the magazines because of the spread of the fire.

Lt William Pearce described the event:

I saw the collier ship steam away from the Glatton, when suddenly the September night was torn by the roar of an explosion that reverberated against the towering cliffs and shook the town to its foundations, sending my tug, berthed against the Prince of Wales pier, rocking crazily. Dense white smoke rose from the Glatton, great flames leaped heavenwards in a pillar of yellow light.

In less than five minutes we were alongside the blazing ship. On the Glatton's deck were dozens of officers and men, terribly wounded. Some were lying prostrate, others writhing in agony from burns. The ship was burning fiercely, for her oil fuel had caught alight. Then someone shouted, "For God's sake flood the magazines!"

With a thrill of horror I realised the awful peril. Fore and aft were two magazines of live ammunition, and if the fire reached them the very town of Dover would be blown to smithereens. There was scarcely a ship in the harbour that wasn't carrying a deadly load – ammunition, depth charges, and mines. Another explosion aboard the Glatton might easily detonate the whole lot.

Running out a length of fire hose we scrambled aboard the Glatton, but instantly fell back. It was almost as though the heat had hit us a blow. How we ever found our way through the scorching suffocating barrage of smoke to the fore end of the ship, where many ratings were trapped, I shall never know.

Vague figures kept looming up – wounded men struggling to escape, officers and ratings who had come aboard to join in the work of rescue. For by now many small craft from the other ships were swarming round the Glatton. There were many grim scenes as such wounded as could be reached were borne away.

A band of ratings had volunteered to flood the fore magazine, or to open the stopcocks and sink the ship. This end of the ship was full of gas; it drove the men back choking and spluttering.

Moored 150 yards away was an ammunition ship called the Gransha.

Image: The ammunition carrier, the Gransha (image courtesy of Historical RFA)

Fearing the flames would cause an explosion which could trigger a secondary explosion on the Gransha (this could have caused devastation on the scale of what happened to the Canadian port of Halifax earlier in the war), Vice Admiral Roger Keyes ordered Glatton to be torpedoed in an attempt to flood the magazines.

Sketch of 'Vice Admiral Sir Roger Keyes (1872–1945), KCB, CMG, CVO, DSO', by the British painter Glyn Warren Philpot. Courtesy of the collection of the Imperial War Museums.

The first torpedo failed to explode because it had been fired too close to Glatton. The second torpedo detonated but was insufficiently powerful to penetrate through her defensive anti-torpedo bulge and Glatton remained afloat, still burning. Larger torpedoes were fired at 8.15pm which succeeded in causing Glatton to capsize - dousing the fire.

Fatalities commemorated by the CWGC total 95, with many others being seriously injured. Most of the dead from this incident are buried in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery.

One of the dead was believed to be a Stoker by the name of 'Robert Snowball'. However, behind this simple name lies a complex story.

Patrick Rafferty (real name Costello)

Among the men enlisting in the Middlesex Regiment in 1915 was someone who called himself 'Patrick Rafferty'. His real name was Cornelius Costello.

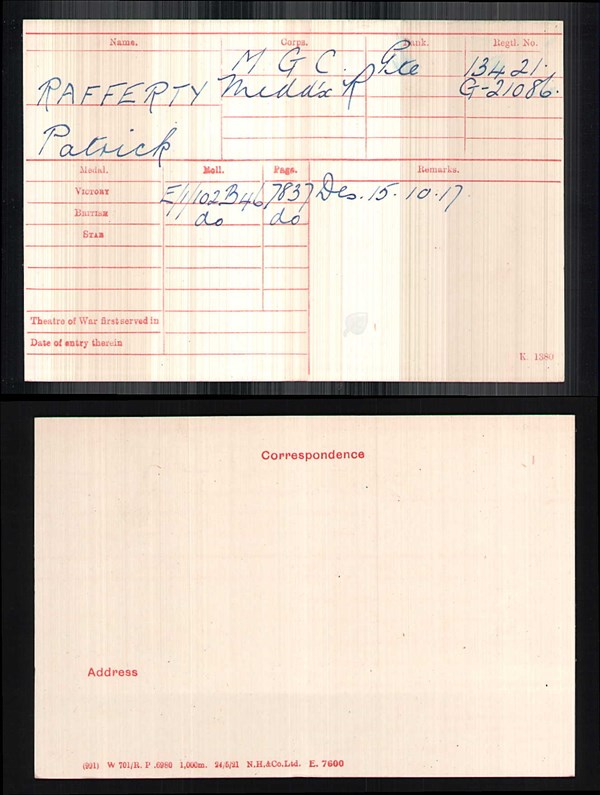

Above: Medal Index Card of Patrick Rafferty

'Rafferty' transferred to the Machine Gun Corps in February 1916 whilst, at the same time, reverting to his real name of Cornelius Costello. Costello (Rafferty) later transferred back to the Middlesex Regiment before deserting in October 1917.

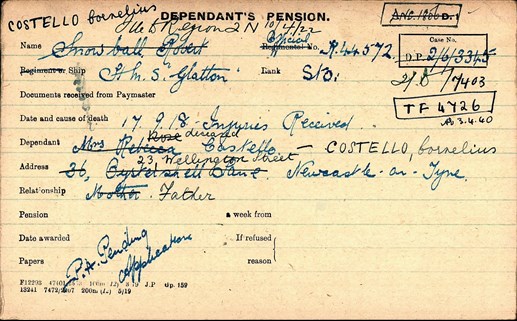

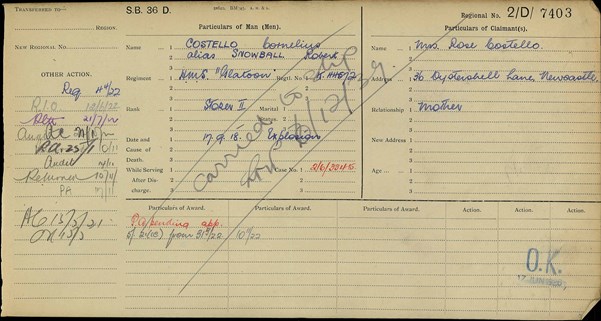

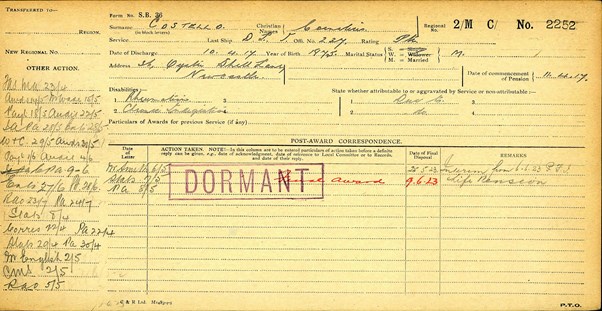

Above: Three records in the WFA's Pension Records for Cornelius Costello

Ralph Bonner

Bonner was - possibly - an equally dodgy character. He enlisted as a stoker in the Royal Navy using the alias of Robert Snowball, the surname being his mother's maiden name. He deserted in November 1917.

Whilst on the run after deserting, Costello (Rafferty) and Snowball (Bonner) met up whilst in the London Bridge area in November 1917. Having had more than a few drinks, the men swapped uniforms. It was whilst in the Royal Navy uniform of 'Snowball' (aka Bonner) that Cornelius Costello was arrested for being drunk. The real Snowball (Bonner) avoided arrest and fled to Ireland, in the process assuming the name of Robert Flanagan. He stayed in Ireland for nine months before returning to his home town of Sunderland.

Results of the exchanged identity...

Costello/Rafferty (now going by the name of Robert Snowball) received 42 days detention by the Royal Navy and, after serving on HMS Redoubtable, he was eventually posted to the brand-new HMS Glatton. He was to die from the injuries sustained in the blast. As mentioned above, 'Cornelius Costello' is buried at Dover (St James's) Cemetery.

John Vaughan describes the events after the war:

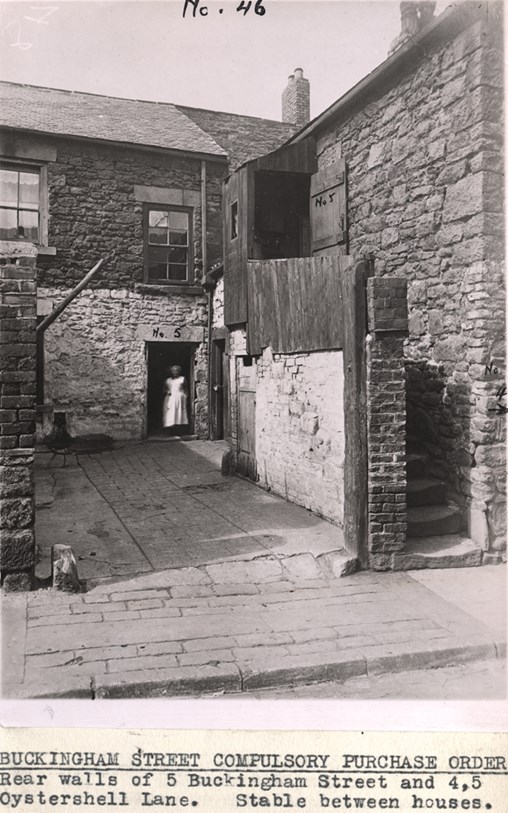

The first hint that something was amiss came after notification of death was sent to Snowball's mother at the address held in Admiralty records - 37 Oystershell Lane, Newcastle-on-Tyne. After a period of time the letter was returned marked 'not known' so the Admiralty tried again, this time addressing the letter to a Mrs Rebecca Snowball of 21 Howich Street, Sunderland, a lady to whom Robert Snowball had made an allotment of his pay in July 1917. Although this letter wasn't returned like the previous one, a communication was instead received from a Mrs Rebecca Costello of 36 Oystershell Lane, Newcastle. In it she complained that, although she had identified the body of her son at Dover, she still had not been officially informed of his death. Her husband confirmed that 'Robert Snowball' was their son, Cornelius Costello.

In July 1921 it was reported by the Ministry of Pensions that Robert Snowball, Stoker 2nd Class, was alive and well and living at 21 Howich Street, Sunderland. The local police were asked to investigate - after all, Cornelius Costello had died on HMS Glatton under the alias Robert Snowball, so who was the person now in Sunderland?

It is without doubt that unravelling of all this took some considerable effort by the police and Ministry of Pensions.

Buckingham Street/Oystershell Lane Newcastle upon Tyne Dept of Environmental Health c.1936

Summary (in case you didn't follow this)

Costello changed his name to Rafferty and enlisted in the Middlesex. Reverting to 'Costello' he joined the MGC but later re-joined the Middlesex. He deserted and assumed the identity of Snowball and was killed whilst working under that name.

Bonner joined the Royal Navy as 'Snowball' and deserted. After meeting Costello, he later became 'Flanagan' but seems to have claimed a pension as 'Snowball'.

Glatton again

The loss of the Glatton seems to have been put down to poor quality workmanship. Investigations revealed that in Glatton's sister ship, HMS Gorgon, folded newspapers had been inserted into empty spaces in the hull where cork lagging should have been used. In addition a number of rivets were missing, which meant that holes were present which could have allowed hot ashes to cause the newspapers to ignite. This, in turn, would have resulted in the paper and corking to catch fire, thus emitting flammable gases and therefore igniting the explosive cordite.

Article by David Tattersfield

Read More:

Acknowledgements:

My thanks to John Vaughan of the Kent and Sussex History Forum for his contribution of the story of Cornelius Costello and to the Dover War Memorial Project for the passage written by Lt Pearce.