Vivian Hicking - a Grimsby Chum in India, drowned 3 June 1919

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Vivian Hicking - a Grimsby Chum in India, drowned 3 June 1919

After the armistice, many men would have been returning to their homes after receiving their discharge from the army, however men were still required not only for the occupation of part of Germany, but also for the continuing garrison duties in the far-flung corners of the Empire. It was in India in June 1919 that tragedy was to strike, causing the death of the last man to be named on the Ravensthorpe War Memorial.

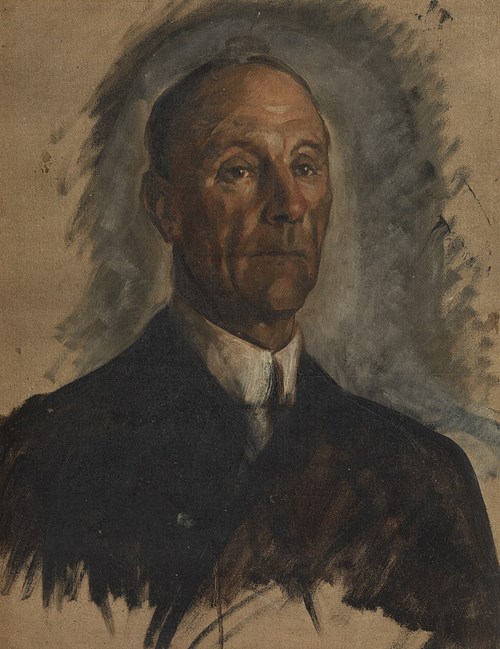

Harold Vivian Hickling, the son of William and Alice Hickling, was born on 20th April 1891.

Above: Harold Vivian Hickling

After attending St. Saviour’s Boys’ School and later Wheelwright Grammar School in Dewsbury he was apprenticed to a firm of lithographers in Leeds probably as a result of his natural talent for drawing; he subsequently worked in Skegness. It was in Skegness that Vivian (as he was known) found himself when war broke out, and volunteered for the army in September 1914.

A local ‘pals’ battalion was being raised at the time under the title ‘The Grimsby Chums’, which when incorporated into the army became the 10th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment, part of the 34th Division. Vivian, was mentioned in the local newspapers, being listed in the Dewsbury News in December 1914 as 'Wheelwright [Grammar School] ‘Old Boy’ serving with the forces.'

Above and below: Wheelwright Grammar School

Above: The Memorial in St James Church, Grimsby to the 10th ('Chums') battalion.

The 34th Division went to France, Vivian’s battalion landing on 9th January 1916. From a letter written a little time later, it seems that Vivian’s active part in the war was not to last very long. According to the letter written to his mother (his father had died), it seems that within a month of arriving in the trenches he was gassed; he wrote: “....I didn’t get long in the trenches did I, just over a month although we had it very bad a time or two. The third time we went in was the Kaiser’s birthday (27th January)....the salient at Bois Grenier, where we were, was nearly levelled off....” Vivian’s letter goes on to describe some spy stories that he had heard (such stories were rife at this stage in the war). After being gassed he was sent to Wimereux, near Boulougne to recuperate, from where he sent further letters to his brother and sisters. In these letters he describes gardening and working in the convalescent camp’s theatre where he had “Collared the scenery painting job”. It seems he spent some considerable time at this camp.

During his stay in the camp, a letter from him to his sister, Beatrice, was reproduced in the Dewsbury Reporter. Part of the letter reads:

'I am getting on as well as can be expected, but am still rather weak. That isn’t to be wondered at as I was in bed for nearly three weeks. It is a pleasant change to be here and to walk about without any equipment on, much different from being up the line, where, as you will see (Private Hickling encloses a very clever sketch of himself in full pack) [unfortunately the drawing has not survived] we carry ‘our houses on our backs’. There is a good recreation room here, with billiard tables etc. and for the thirsty a bar where one can get French beer, of which the more one drinks, the more sober one gets - so I am told. We had a thunderstorm last night and it is very warm today. I hope it continues so.......A character I have come across here is Johnson of Shoreditch, who on pay nights is generally to be found in some neighbouring estaminet, making an offer in his native tongue of ‘50 Francs for any man in the haase as’ll stand up and ’ave free raands wiv’im’....In spite of [Johnson’s] little idiosyncrasies [he has] his tender side which is laid bare in his affection for ‘Spot’. Spot is a canine acquisition with a wealth of affection, an appalling appetite and no family tree. He has come to stay, at least his collar has disappeared. How’s golf going? I wouldn’t mind a walk round Coxley [valley - an area of woodland about four miles from Ravensthorpe] though I’m afraid it would be rather a slow one.'

A further mention of Vivian appears in the Dewsbury News in May when he writes again from the convalescent camp to the Headmaster of St. Saviour’s Boys’ School, thanking them for a parcel: 'The contents were very acceptable indeed and they were appreciated greatly by the chaps in our tent. At present I have not much news as a convalescent camp is scarcely a place for excitement.'

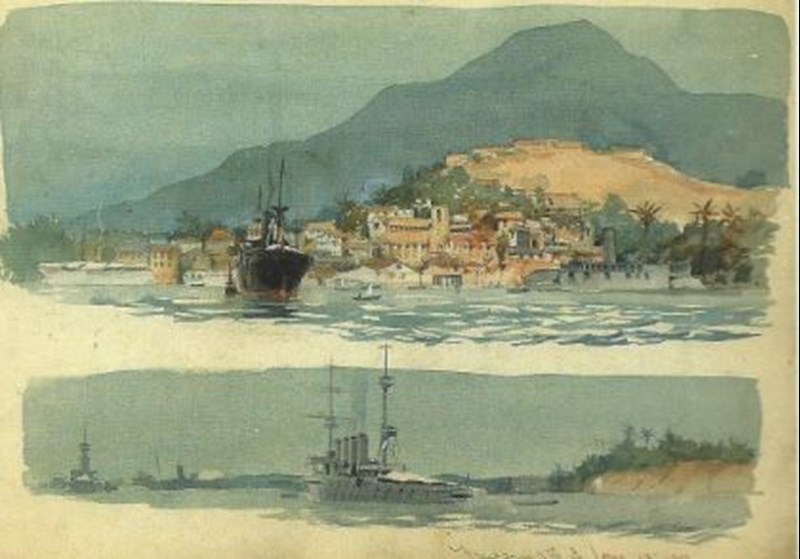

After his recovery, Vivian would have been medically examined, and was declared unfit for the rigours of the Western Front. Parts of the British Empire, however, still required a military presence and he was therefore transferred to the South Staffordshire Regiment, and after a period of leave at home was posted to ‘A’ Company, 1st Garrison Battalion, and sent out to India in March 1917. The journey, via Sierra Leone, and Cape Town and Durban in South Africa took many weeks, but gave him ample opportunity to draw and paint the various things he came across, including the shipping in the harbours and the docks at the ports en-route.

Above: Painting by HV Hickling. Uncaptioned, but clearly the troopship to India

Above: Freetown Harbour, Sierra Leone. March 28th, 1917. HV Hickling

He arrived in India, probably in May 1917, being stationed near Bombay. Whilst he was away from the Western Front, he was not exactly out of danger; in his weakened condition he would have been more prone than others to the illnesses that can be caught in that part of the world. Over the next two years he contracted dysentery, typhoid fever and at Christmas 1918, influenza; thankfully he managed to survived all these.

A letter to his mother dated 6th February 1919 describes a 'Big Hindoo wedding....the bridegroom was 10 years old and is the heir to £7,000,000. The bride was only six years old but she chucks another £4,000,000 into the pool. There were all kinds of entertainment, Hindoo plays, Dancing Girls and jugglers etc...” He went on to describe how he was there as a member of the battalion band, but they were not overworked, all they were required to do was '...play ‘Tipperary’ about twenty times by request, it is the only English tune they know ...'

Another letter, dated 18th March was received by his mother in Ravensthorpe, this described the arrival of Earl Jellicoe ('an insignificant little beggar'), the former First Sea Lord ('...of course we had to stand in the sun for a few hours waiting').

Above: Earl Jellicoe painted in 1918 (Philpot, Glyn (RA), IWM ART1322)

At the end of May 1919 he wrote to his mother at 719 Huddersfield Road, Ravensthorpe, indicating he was in good spirits; the letter added that he was at Calabar, near Bombay on India’s west coast.

Vivian's home address (centre property) in Ravensthorpe from Google Street view (C) Google Street View 2021

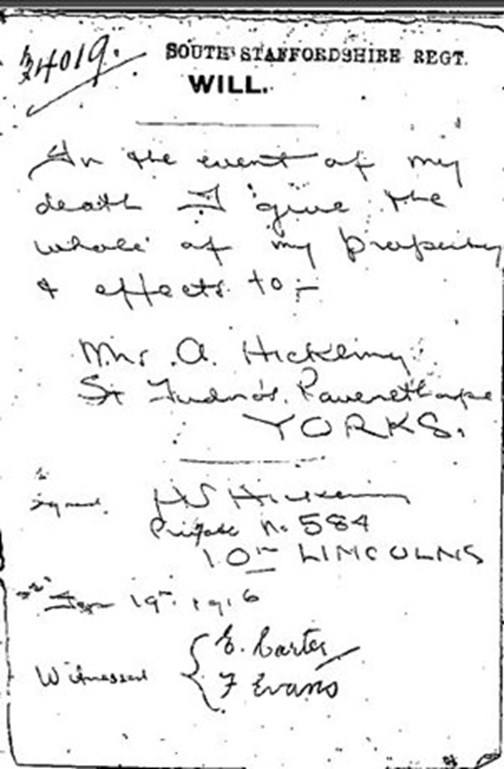

On Tuesday 3rd June 1919, Vivian was on the jetty at Pilot Bunder, near Calabar, when a huge wave swept him into the water. Despite a boat being launched to try and save him, because he was a non-swimmer, he had drowned before it reached him. The location of this is adjacent to the 'Gateway of India' in Bombay (Mumbai). Vivian was 28 years of age. He left a will which was dated 1916 - probably just before he entered the trenches in France for the first time.

Above: Gateway of India - it was near here that Vivian was swept to sea and drowned.

Vivian Hickling was buried at Sewri, but between 1955 and 1960, burials of both wars were removed from this civil cemetery to Kirkee War Cemetery where maintenance in perpetuity could be assured. Only one Second World War burial now remains at Bombay (Sewri) Cemetery.

Above: The sole grave in Bombay (Sewri) Cemetery - it is here where Vivian was buried in 1919.

Above: The Kirkee Memorial to the Missing

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice Chairman, The Western Front Association