Walking in Walter Tull’s footsteps: The Final Days

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Walking in Walter Tull’s footsteps: The Final Days

The life of Walter Tull continues to fascinate and hold the interest of military historians, social historians, campaigners, politicians and football fans alike. He has been the subject of a number of TV documentaries and dramas, relating his experience as a black, working class sportsman and soldier, highlighting his indomitable spirit, exceptional character and resilience, overcoming the double deficit of class and race. A real trailblazer who defied his humble and unpromising beginnings to excel in the combative and competitive field of sport, and its more deadly and far more serious relation, war.

Above: 2nd Lieutenant Walter Tull, 17th and 23rd (1st and 2nd Football) Battalions Middlesex Regiment (Image: blackhistorymonth.org.uk)

His backstory has been well aired, but warrants retelling. He was born in Folkestone, Kent, on 28 April 1888 to a carpenter and joiner named Daniel Tull. A descendant of slaves, Daniel left his birthplace Barbados for St Lucia in 1873 in pursuit of higher wages, and thence for England three years after that. Settling in Folkestone, he practiced his faith at the Grace Hill Wesleyan Chapel, where he met and married a local girl, Alice Elizabeth Palmer. We can only imagine the challenges they faced as an interracial couple in Victorian Britain. Fortunately his in-laws were a supportive couple, enlightened before their time, who welcomed Daniel into the family with open arms.

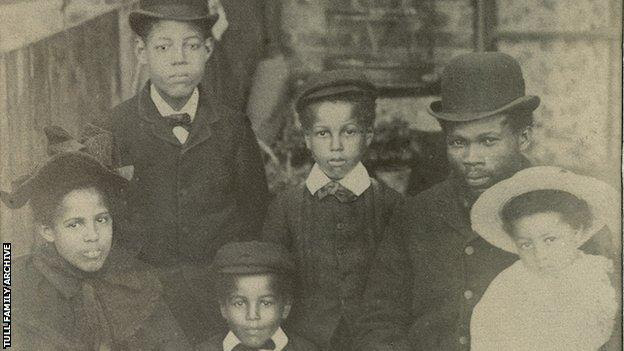

Daniel and Alice lost their first child, a girl named Bertha born in 1881, at the tender age of five weeks. This tragedy can only have made the birth of a son, William, a year later in April 1882, that more precious. William was followed by a girl, Cecilia, in March 1884; a boy, Edward, in June 1886; Walter himself in April 1888;and the youngest, a girl, Elsie, in November 1891. The 1891 census, taken on Sunday 5 April whilst Alice was still pregnant with Elsie, shows Daniel aged 35, Alice aged 38, William aged 9, Cecilia aged 7, Edward aged 4 and Walter aged 2, at 51 Walton Road, Folkestone. Daniel, buoyed by his faith, was a conscientious and hard-working father. He needed to be, with a wife and five little ones to support. Keeping one’s head above water as a member of the working class in late nineteenth century Britain was an existential and ongoing challenge, the prevailing system of laissez faire economics kept wages suppressed. The parents of a large family walked a tightrope; good health and fitness to work were essential to provide and care for their brood.

Above: Tull Family portrait, young Walter front and centre (Image – Tull Family Archive)

The family’s fortunes took a downward turn in 1893 when Alice Tull was diagnosed with breast cancer, and the disease progressed, until just two weeks before Walter’s seventh birthday on 14 April 1895,she died, plunging the family into an uncertain and insecure future. The Palmer family would come to the rescue. Alice’s niece, Clara Palmer aged 26, married Daniel on 17 October 1896 becoming stepmother to Walter and his siblings. It was a heavy responsibility for young Clara, she had to swiftly learn the art of motherhood, although it was clearly not just a marriage of convenience, as on 11 October 1897 Clara presented Daniel with a baby girl named Miriam.

But bad luck continued to dog the family, just two months after the birth, Daniel Tull died suddenly from heart disease, leaving Walter now fatherless as well as motherless. The family descended into poverty, and despite parish relief Clara couldn’t keep afloat: she turned to the Methodist Church for help. As a result Walter and his elder brother Edward were placed in the Methodist Children’s Orphanage at Bethnal Green, London, to ease the financial burden. Walter and Edward entered the orphanage on 24 February 1898, Walter was 9 years old, Edward was 11.The shock of leaving the family must have been seismic for the two youngsters. It became that much worse then, as this separation was compounded on 14 November 1900 when Edward, at the age of 14,left the children’s home, having been adopted by a Glasgow dentist and his wife: the brothers left utterly bereft.

Above: The Orphanage, Bonner Road, Bethnal Green (Image – childrenshomes.org.uk)

Walter would spend a total of 7 years at the orphanage, eventually securing an apprenticeship as a printer at the age of 17 in 1905.But his career would proceed in a different direction. He had exceptional ball-playing skills, accomplished at sport from an early age he represented the orphanage at football and cricket, playing at Victoria Park in the East End and at Stamford Hill playing fields just south of Tottenham.

Above: The Orphanage Football XI, c1902. Walter is front row, second from left (Image – pressat.co.uk)

He was soon spotted as a rising star, Clapton FC (not to be confused with Clapton Orient FC, forerunners of Leyton Orient), one of the leading amateur sides in the country, signed him up in 1908. In his first season he helped Clapton win three trophies, the FA Amateur Cup, the London Senior Cup and the London County Amateur Cup. His talent was there for all to see, and the bigger clubs swiftly took notice. He was snapped up by Tottenham, signing professional forms on 20 July 1909.

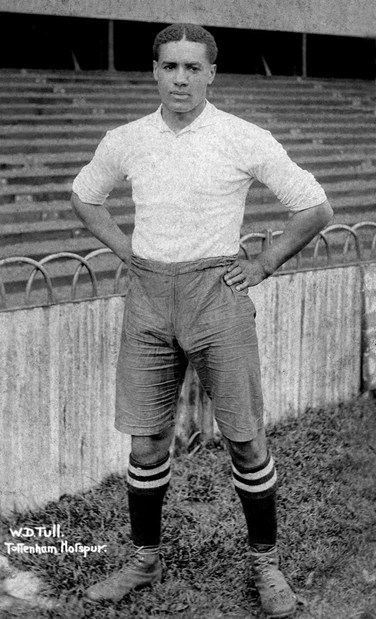

Above: Walter in Tottenham Hotspur’s colours (Image – footballandthefirstworldwar.org)

Tottenham had recently lost their star player, Vivian Woodward, an England international and prolific goal-scoring centre forward who had captained a triumphant Great Britain side at the 1908 Olympics to a gold medal. Tull had big boots to fill, but it was not a like-for-like replacement, Walter was an inside forward, a creator and supplier rather than an out-and-out finisher of goals. In modern parlance his contribution would be measured in ‘assists’.

His signing attracted media interest, the Barnsley Chronicle reported it thus: A gentleman of colour has been signed by Tottenham Hotspur. Tull is his name, and as an amateur he helped Clapton to win the Amateur Cup and the London County Amateur Cup. He is 21, weighs 11 stone, and stands 5ft 8in. The West Indian (sic) has the distinction of being the only coloured player operating in first class football[1].

Above: Tottenham Hotspur FC 1909-10, Walter is seated cross-legged front row, third from the left (Image – www.tottenhamhotspur.com)

Tottenham were developing into one of the biggest and most glamorous clubs at the time, they had won the FA Cup in 1901, breaking the stranglehold that the clubs from the north and the midlands had on the game, becoming the first professional team from the south to achieve major success (it would be another 20 years before the trophy returned south when Spurs triumphed again in 1921).

Walter joined the club’s summer tour of Argentina and impressed the Tottenham management with his cultured passing skills and cerebral approach to the game, so much so that he was selected for the first team when the season proper started. A match report of one of the early games, a 2-2 draw with Manchester United on 11September 1909,stated that ‘Tull revealed an excellent knowledge of the game. His control of the ball and his passes were alike excellent’ [2].

Above: Tottenham Hotspur FC 1910-1911, Walter is seated cross-legged front row, extreme right (Image – Tull Family Archive)

It seemed that Walter was destined for a stellar career, but he lasted just two seasons, only making 10 first team appearances and scoring 2 goals. The reason for his departure is believed to relate to a match against Bristol City on 2 October 1909. In this game, Walter was targeted by some of the Bristol fans, suffering a torrent of racist abuse. In a match report at the time, headlined ‘Football and the Colour Prejudice’, the correspondent wrote:

He is the Hotspurs’ most brainy forward. Candidly, Tull has much to contend against on account of his colour. His tactics were absolutely beyond reproach, but he became the butt of the ignorant partisan. Once, because he floored Annan with a perfectly fair shoulder charge, a section of the spectators made a cowardly attack upon him in language lower than Billingsgate. Let me tell these Bristol hooligans (there were but few of them in a crowd of nearly twenty thousand) that Tull is so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football whether they be amateur of professional. In point of ability, if not in actual achievement, Tull was the best forward on the field[3].

Following that game, Walter was dropped to the reserves, only playing the odd game for the first XI, and would play his last first team game against Woolwich Arsenal in April 1911.

Above: Tottenham Hotspur FC 1911-1912, Walter is seated second from the right second row (Image – waltertull.org)

It seems incongruous then that Walter’s career was stalling when his fame was beginning to spread far and wide. The Trinidad & Tobago Mirror printed an article on Monday 18 October 1909 – syndicated from the Athletic News and originally published nearly a month previously on 20 September (just a week after the above mentioned match between Spurs and Manchester United) – headlined ‘Tottenham’s Man of Colour’:

The development of young talent is undoubtedly very largely responsible for the present position of Tottenham Hotspur. Boreham, Middlemiss and R. Steel are striking examples, and It would not be straining the argument to include young players like Coquet, Burton, Wilkes, Darnell, Minter and Curtis. This season they have introduced yet another youngster in Walter Daniel Tull, who will, if we mistake not, leave an indelible mark in the records of the famous club. Tull has the rare distinction of being the only coloured player operating in first-class Association football. He is the son of a West Indian gentleman who married an English lady, and was born in Folkestone just twenty-one years ago. When nine years of age he came to London, and it is in the great metropolis that he has gained his extensive knowledge of football. He played in a comparatively minor class until last season, when he joined the English Amateur Cup holders, Clapton. He quickly established a claim to the inside-left position, and rendered the North London Club Invaluable assistance in winning the Amateur Cup and the London Senior Cup. The success of Tull was such that in March last, only six months after he had emerged from the obscurity of junior football, he was induced to sign amateur forms for the 'Spurs, and in April he assisted the White Hart Lane team to win the London Professional Charity Cup. Thus he is the proud possessor of three gold medals as the reward of his first season's efforts in the senior ranks.

Tull became a professional at the end of last season, and was one of the Tottenham team which toured the Argentine last summer. His play in the August practice matches was such that the Tottenham selectors gave him instant promotion to the first team, and […] he demonstrated unmistakably against Manchester United a week ago that he is a player of very high merit. There is much of the Corinthian style in his play. His passes are invariably low and accurately placed. He gave evidence of ability as a marksman which will gain him a place in the goal-scoring records, and in every way he showed himself thoroughly conversant with the finer points of forward play. We commend the Tottenham directors upon their action in persevering with a young player of such promise[4].

Above: Walter in action for Spurs (Image – footyfair.com)

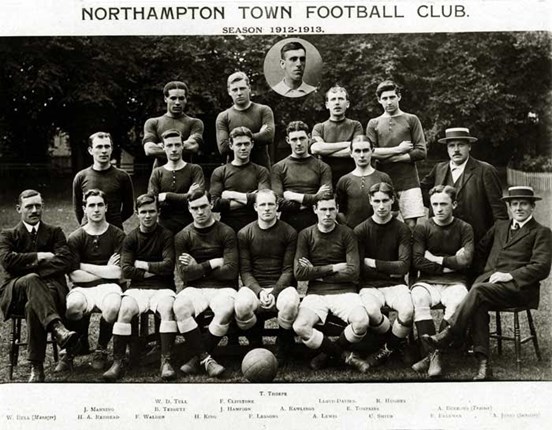

It is not known why Tull lost his place in Tottenham’s first team, but one suspects that the racist abuse he suffered during the game against Bristol City was instrumental in that decision. Did the board of directors take the view that a recurrence of this verbal abuse might affect the team’s morale or their performance overall, or that the media attention it might attract was too controversial, too embarrassing? The net result was that, in October 1911, Walter left Spurs for Northampton Town. Tottenham’s loss was Northampton’s gain, and he would have a successful career with ‘the Cobblers’, going on to make 111first team appearances for the club, scoring 9 goals.

Above: Northampton Town Football Club 1912-1913, Walter is on the left of the back row (Image – blacklistedculture.com)

Upon the outbreak of the Great War, Walter was the first Northampton Town player to join the army, enlisting on 21 December 1914 with the newly-formed17th (Service) Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment, known as the ‘Footballers Battalion’ consisting of players, club officials and supporters. He eventually sailed for France on 18 November 1915.

Above: Great War Recruiting Poster urging Spurs’ players, staff and supporters to enlist with the 17th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (Image – www.haringey.gov.uk)

The 17th battalion entered the front line for the first time on 9 December, between La Basseé and Loos. They completed their first tour of duty on 22Decemberand retired to billets in Beuvry for the festive period. On Christmas Eve, Walter and his colleagues were treated to some seasonal entertainment, the war diary states: ‘The evening of the 24th was devoted to a concert for the men which was held in the recreation room. Needless to say full advantage was taken of the privilege’. The following day the diary reports: ‘The 25th being Xmas day as far as possible the usual festivities were indulged in’[5].Walter would rise through the ranks rapidly, being promoted three times in quick succession and eventually reaching the rank of Lance Sergeant.

The battalion fell into the remorseless routine of trench warfare, alternating between the front line, reserve trenches, training, musketry practice and rest at billets. Out of the line, football was the most popular form of recreation favoured by the men of the BEF, and unsurprisingly the 17th were very good at it. They beat the 13th Essex 9-0 on 7 January 1916; the 2nd South Staffs 6-0 on 10 January; and following these thrashings, the rest of the 6th brigade fielded a combined XI, comprising their best players from the other three battalions, in an effort to beat the 17th Middlesex, but to no avail, they were defeated 3-1 on 15 January.

Above: Walter as a non-commissioned officer earlier in the war (Image – www.kentonline.co.uk)

The attritional nature of trench warfare, the constant shelling and sniping, the acutely challenging conditions they lived under, rats and lice infested, combined with the wet, very cold winter, had an erosive effect on Walter, and he was diagnosed with trench fever, returning to England on 9 May 1916 for treatment. It was some time before he would be fit for duty, a newspaper article dated 19 August 1916 reported that: ‘Walter Tull, the Northampton half-back, who is attached to the Footballers’ Battalion, is now convalescent, after being in hospital for three months with pneumonia.’ [6]

Upon his recovery and return to full duties, he disembarked in France in the Autumn, being posted to the 23rd Battalion Middlesex Regiment, sister battalion to the 17th and known as the 2nd Footballers Battalion. He joined them on 29 October 1916, taking part in the closing three weeks of the Battle of the Somme.

Walter was granted leave at the end of the year, just in time to catch the end of the festive period on Boxing Day, and it was around this time that his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Alan Roderick Haig-Brown – also a gifted footballer who had made a handful of appearances for Spurs’ before Walter’s time c.1901-1903 – supported Tull’s promotion to the officer class. This was a very bold move by Haig-Brown, who must have been well aware of army regulations barring ‘men of colour’ from holding rank.

Above: Walter as a newly-commissioned subaltern (Image – sportsgazette.co.uk)

Clearly, Walter was as talented a soldier as he was a footballer, his rapid promotion through the lower ranks was evidence of this, and it can be seen that Haig-Brown saw a kindred spirit in Tull, shrewdly noting his qualities, recognising his martial prowess and leadership potential. His judgement of Walter’s character must have been crucial, as a well-respected and much-loved CO his opinion carried a compelling gravitas, so much so that the regulations were somehow overlooked and the promotion was confirmed. Walter duly graduated from his officer training course, and he appears in the London Gazette on a list under the heading: Special Reserve of Officers: The undermentioned from an Officer Cadet unit to be 2nd Lts:-30 May 1917 [7].He was posted back to the 23rd Middlesex, back amongst his footballing brethren, on 4 August 1917. He saw action in the Battle of Passchendaele in late September: thereby, in tandem with the Somme, taking part in the two most infamous battles fought by the British in the Great War.

Above: Walter Tull with two officer colleagues (Image – Tull Family Archive)

Events in Italy dictated the next phase of Walter’s war. On 24 October 1917, the Central Powers’ launched an offensive at Caporetto (known today as Kobarid in modern day Slovenia, close to the Italian border). Up to that point, the Italians had been more than holding their own against the Austro-Hungarian army, making significant gains, and as a result a request was sent by the latter to their German allies for reinforcements. A positive response was received and the combined forces of the Austrians, Magyars and Germans attacked and sent the Italian army reeling: it was feared that Italy could collapse and be knocked out of the war altogether, allowing the redeployment of substantial numbers of troops to threaten the British and French on the Western Front. Much to Douglas Haig’s dismay, five British Divisions were removed from his command, to join six French Divisions in bolstering Italy’s resistance. The 41st Division, including the 23rd Middlesex, were one of the five chosen.

Walter distinguished himself during the Italian campaign, taking part in a number of raids over the festive period 1917/18, crossing the bitingly cold waters of the River Piave to harass the Austrian and German troops deployed on the east bank, taking prisoners and gathering vital intelligence. Major-General Sidney Lawford, GOC of the 41st, made special mention of Walter’s intrepid spirit and exceptional leadership:

I wish to place on record my appreciation of your gallantry and coolness. You were one of the first to cross the River prior to the raid on 1/2 January 1918 and during the raid you took the covering party of the main body across and brought them back without a casualty in spite of heavy fire.

General Sir Herbert Plumer, in command of the expeditionary force in Italy, specifically referred to the operation in his Despatch published in the London Gazette:

On 1 January our biggest raid was carried out by the Middlesex Regiment. This was a most difficult and well-planned operation, which had for its objective the capture and surrounding of several buildings held by the enemy to a depth of 2,000 yards inland, provided a surprise could be effected. Two hundred and fifty men were passed across by wading and some prisoners were captured, but, unfortunately, the alarm was given by a party of 50 of the enemy that was encountered in an advanced post, and the progress inland had, therefore, in accordance with orders, to be curtailed. The re-crossing of the river was successfully effected, and our casualties were very few. An operation of this nature requires much forethought and arrangement, even to wrapping every man in hot blankets immediately on emerging from the icy water [8].

One of Walter’s comrades, Private Thomas Billingham, was granted leave in the new year. The Northampton Mercury newspaper, dated 18 January 1918,reported that:

A visitor to the “Echo" office on Saturday was T. Billingham, who, footballers will remember, played in goal for the Cobblers Reserves, and at the outbreak of war was playing for Leicester Fosse. He is a private and physical instructor and is at home on leave from Italy. The weather there is bitterly cold, but warmer weather is due next month. Private Billingham states that Walter Tull, the old Cobbler, is in Italy and is now a lieutenant. On Boxing Day, he took part in a raid, but the enemy had made himself scarce, and only three prisoners were found[9].

Walter’s time in Italy was coming to an end. It appears that he was also granted leave to England, as it was reported that he went to see his old club, Spurs, in action on 23 February 1918: a newspaper report headlined ’Risen From the Ranks’ relates the following:

Among the interested spectators at the Chelsea v, Tottenham Hotspur match at Stamford Bridge last Saturday were Capt. Barnfather, the outside left of Croydon Common and formerly of Barnsley; Lieut, Walter Tull, the Northampton and Tottenham Hotspur half-back; and Lieut. Gordon Hoare, the Fulham inside left and amateur international. All these three players have risen from the ranks[10].

On 8 March 1918 the 23 Middlesex Battalion, as part of the 123 Brigade of 41 Division, arrived back in France. They had no idea what was coming down the track.

On 21 March 1918, the Germans launched a massive offensive on the Western Front named the Kaiserschlact or the Kaiser’s Battle, also known as the German Spring Offensive, in an effort to smash through the British lines and end the stalemate, driving them into the sea and a forced evacuation across the Channel.

The Germans had reinforced their armies in France and Belgium with 500,000 extra troops released from the Eastern Front as a result of the collapse of Russia, aided by the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917. This gave them a substantial numerical advantage of 192 infantry divisions against the combined Allied total of 169.

The Germans had a window of opportunity to make their superior numbers count before the US – having entered the war in April 1917 – could fully mobilise their forces in Europe. Over a million shells were fired in the first five hours of the offensive at a rate of 3,000 a minute, both high explosive and gas shells, and the bombardment was followed up by elite regiments of storm troopers descending on the British lines in an onslaught that had the Tommies reeling.

The Germans made spectacular gains, driving the British back by up to eight miles. Over the course of the coming months they would gain ten times the ground the Allies had won in 1917.It was nothing less than a juggernaut, and the British would be hanging on by a thread, having to absorb the shock of the assault by falling back in good order without breaking their line in an organised withdrawal and retrenchment.

It was against this backdrop that the 23 Middlesex were deployed near Beugny, a farming village on the Bapaume-Cambrai Road. The Battalion’s War Diary details the events of the succeeding days, the last of Walter’s life:

Bouzincourt 22 March 1918 09:00am

Battalion marched to Achiet-le-Petit via Miramont. 2:00pm Dinner served on roadside. Blankets dumped. Bombs and ammunition issued to Companies. 3:30pm Lorries took battalion (less details) to Monument on Arras-Bapaume Road. Bivouacked in field until midnight. 12:15am Marched to Beugny via Fremicourt to take up support position in front of BEUGNY. Battalion disposed in shelters of hastily dug trenches by dawn. BHQ – cellar in Beugny.

Casualties 12 OR Wounded. 8 Killed. 2 Missing. 2nd Lieutenant S R Hylands Wounded} by bomb at detail camp. 8 OR rejoined Battalion[11].

Above: In October 2023, the author led a touring party retracing Walter’s journey over the last few days of his life. Here they are returning from the old front line near Beugny where Walter was deployed on the 23 March 1918 (Photo – Stephen Mulford)

The following morning, the storm broke, the War Diary continues:

Beugny 23 March 1918 10:30am

Enemy heavily bombarded BEUGNY. Also shelled our positions to the left of village. Enemy attacked. Battalion retired to conform to line on right and left flanks. ‘D’ Coy covered the retirement by rapid fire and L.G. fire. New line (GREEN LINE) taken up astride BEUGNY-FREMICOURT ROAD. Relieved on night 23/24 and bivouacked near aerodrome at FAVREUIL.

Casualties on 23rd: 3 Killed. 36 Wounded. 12 Missing. 1 Missing believed killed. 3 Missing believed wounded. 1 evacuated sick[12].

Above: The author quoting from the 23rd Middlesex War Diary at Favreuil, where Walter spent the night of the 23/24 March 1918 (Photo – Stephen Mulford)

They had a brief respite at Favreuil before the retirement resumed:

Favreuil 24 March 1918 11:30am

Took up reserve line near FAVREUIL to the rear of HUN DUMP late in the afternoon the front line commenced a retirement reaching the Reserve Line where they were reorganised and placed into position in the Battn sector. About 9pm orders were received to withdraw to a new line at MONUMENT. This was done – the men digging in conjunction with RE until dawn.

Casualties on 24th: 13 Killed. 57 Wounded. 6 Missing. 6 Missing believed killed. 22 missing believed wounded [13].

Above: Monument aux morts de la guerre de 1870-1871. It was in the fields adjacent to the Monument on the Arras – Bapaume Road that Walter was killed (Photo – Stephen Mulford)

Above: The touring party at the Monument aux morts de la guerre de 1870-1871, Bapaume, France (Photo – Stephen Mulford)

The Monument sector was named after the Monument aux morts de la guerre de 1870-1871that stands at the crossroads of the Arras-Bapaume Road and the Biefvillers lès Bapaume-Favreuil Road, commemorating the French dead who fell at the Battle of Bapaume in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. It was in the fields nearby that Walter fell:

Monument 25 March 1918 8:00am

Shelling of our line commenced. Enemy attacked shortly afterwards compelling the troops to withdraw across the ARRAS-BAPAUME ROAD to the line held by the Battn. The enemy continued to push forward in massed formation. It was not until the units on both left & right had retired that the Battn commenced an orderly withdrawal by platoons. Casualties were heavy and the enemy reached the trenches in considerable numbers as Battn HQ commenced to withdraw. During the day other lines were taken up (1) Along the railway embankment behind BIHUCOURT (2) at AICHET-LE-PETIT. The division was relieved during the night 25th/26th. The battalion assembled (via BUCQUOY) at GOMMECOURT and took up a reserve line in old trenches there for the night.

Casualties on the 25th., 13 killed, 61 wounded, 30 missing, 1 missing believed killed, 7 missing believed wounded.

Killed: 2nd Lt. W D Tull, 2nd Lt. T J Pitty.

Wounded: a/Capt. W Hammond MC, Lieut. R A Green, 2nd Lt. G Barton.

Missing believed killed: Lt. Col. A R Haig-Brown DSO.

Missing: a/Capt. B T Foss MC*.

Evacuated sick: 2nd Lt. J Jennings[14].

*Captain B T Foss MC although shown on records as missing on 23/03/1918, was found to have been taken as a Prisoner of War and repatriated on 29/11/1918,ref: 3537.

Walter’s commanding officer Alan Haig-Brown also fell this day. Unlike Walter, his body would be identified and formally recovered and he was buried at Achiet-le-Grand. Like Walter, he was a popular and well respected officer that would be sorely missed by the Battalion. There is no doubt that he was a champion for Tull, recommending him for promotion, evidence of an enlightened and progressive attitude, a man ahead of his time.

Above: Lt. Col. Alan Roderick Haig-Brown, Commanding Officer, 23rd Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (Image – england1418.wordpress.com) and Achiet-le-Grand Communal Cemetery where he lies (Image: ww1cemeteries.com).

Above: Alan Roderick Haig-Brown in the colours of Old Carthusians 1903 (Image – Wikipedia)

Above: The author paying his respects at Walter Tull’s Commanding Officer’s graveside, Achiet-le-Grand Communal CWGC Cemetery, France, October 2023 (Photo – Stephen Mulford)

Walter died leading from the front, directing his men in a fighting withdrawal against immense odds: the War Diary’s mention of the enemy as attacking in ‘considerable numbers’ suggests that the British were outnumbered. One of the eye witnesses to his death was the above mentioned Thomas Billingham:

In a chat with Pte. T. Billingham, the Leicester goalkeeper the other day, he told me that Lieut. Walter Tull, of the Footballers’ Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, whose death was such a blow to his many friends, was killed by a machine gun bullet which entered his neck and came out just below his right eye. Billingham was about 30 yards from him when he was hit, and was the first to go to his assistance. He only lived two minutes, however, and Billingham carried him some distance in the hope of securing for him a decent burial, but had to leave him on account of the Germans’ rapid advance. Tull, he adds, will be greatly missed. He was a thorough gentleman and was beloved by all[15].

Such was the regard that he had for him, Thomas bravely attempted to retrieve Walter’s body, attempting to carry him back to the British line, pursued by hordes of German stormtroopers. He realised it was a hopeless task, to carry on would have meant either, at best, his capture as a prisoner of war, or at worst, his own death. Reluctantly laying Walter’s body down, unencumbered, he made good his escape.

The respect and affection that Walter was held in was universal, shared by the men under his command, his peers amongst the subaltern ranks, and his commanding officers alike. Walter’s brother Edward received a number of letters after his death paying tribute, including from Major Poole DSO OBE, who contravened Army regulations when he mentioned the proposed award of the Military Cross prior to any formal or official authorisation of the said award:

"[He] was very cool in moments of danger & always volunteered for any enterprise that might be of service. He was recommended recently for a Military Cross. He had taken part in many raids. His courage was of a high order and was combined with a quiet & unassuming manner."

2nd Lieutenant Pickard also wrote to Edward in glowing terms, also breaching official regulations:

Allow me to say how popular he was throughout the Battalion. He was brave and conscientious; he had been recommended for the Military Cross & had certainly earned it; the commanding officer had every confidence in him & he was liked by his men. Now he has paid the supreme sacrifice pro patria; the Battalion & Company have lost a faithful officer; personally I have lost a friend. Can I say more! Except that I hope that those who remain may be as true & faithful as he.

We have no idea why the Military Cross was never awarded to Walter Tull, but as with the cutting short of his Spurs career, we can only speculate as to the reason why. However it does seem extraordinary, and not a little suspicious, that his commanding officer’s recommendation was either ignored or rejected outright.

His passing was reported in newspapers across the land. In Folkestone the local press printed:

TULL – March 25th, killed in action in France, Second-Lieut. Walter D. Tull, Middlesex, youngest son of the late Mr. Daniel Tull, of Folkestone, aged 29 years. Deeply mourned by his brothers and sisters [16].

And in Northampton:

Tull, Lieut. Walter, Middlesex Regiment, killed in France; well-known as a member of the Cobblers' football team, to which he was transferred from Tottenham Hotspur. Enlisting two years ago gained his commission by his great ability and merit, which won for him mention in despatches [17].

Walter is commemorated on the memorial wall of the Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery in Arras. It has become a shrine to this remarkable man. Underneath his inscribed name, upon the ledge at the foot of the wall, stand numerous small wooden crosses that have been respectfully placed by pilgrims and admirers.

Above: Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery, Arras (Image – ww1cemeteries.com)

Above: The author speaking at Walter’s inscription on the memorial wall, Bay 7, Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery, Arras (Photo – Stephen Mulford)

Such is the interest in Walter’s story, and the need to recognise and respect the dignified, honourable and heroic manner in which he lived his life, that numerous memorials, sculptures and commemorative plaques have been installed in Folkestone, Tottenham and Northampton. In the absence of a known grave, these sites of contemplation and consolation allow us to pay our respects and honour his contribution to sport, society and country.

Above: The Walter Tull Memorial, Sixfields, Northampton (Image – www.ntfc.co.uk)

Above: Commemorative blue plaque at 77 Northumberland Park, Tottenham, Walter’s former home (Image – www.haringey.gov.uk)

Walter lives on in our memories, and also through the work and research of military historians such as Andy Robertshaw, who has worked as an advisor and Great War expert on War Horse and 1917. Andy has painstakingly tracked the possible whereabouts of Walter’s body [18]. Using existing records, including those from the War Graves Commission, he believes that Walter was originally buried in a mass grave dug by the Germans during the 1918 Spring Offensive. After the Armistice, the CWGC carried out a recovery process by consolidating scattered burial sites into existing cemeteries, one of which was the Heninel-Croiselles CWGC Cemetery. Soldiers’ remains were exhumed and brought in from a wide area surrounding this site, including the mass grave dug by the Germans. The cemetery holds 307 British and Commonwealth graves, with 104 unknown soldiers amongst them. Andy believes that Walter lies at rest here with his brothers-in-arms, a hero and a role model for all of us, for all time.

Above: Is this Walter Tull’s final resting place? Heninel-Croiselles Road CWGC Cemetery (Image – cwgc.org)

Article contributed by Paul Blumsom

References

1. Barnsley Chronicle – Saturday 18 September 1909, p.2.

2. Athletic News – Monday 13 September 1909, p.5.

3. Daily News (London) – Monday 4 October 1909, p.8.

4. Mirror (Trinidad & Tobago) – Monday 18 October 1909, p.7. (syndicated from the Athletic News dated Monday 20 September 1909, p.1.)

5. WO/95/1361/2/1 War Diary 17th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 17/11/1915 to 30/04/1917, The National Archives.

6. Star Green ‘un – Saturday 19 August 1916, p.1.

7. Supplement to the London Gazette, 16 June 1917, p.5970.

8. Supplement to the London Gazette,9 April 1918, p.4430.

9. Northampton Mercury – Friday 18 January 1918, p.4.

10. Star Green ‘un – Saturday 02 March 1918, p.2.

11. WO/95/2639/3 War Diary 23rd Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 01/03/1918 to 28/02/1919, The National Archives.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. A contemporaneous Northampton Independent Newspaper article quoted on Clapton FC’s website:Walter Tull – Clapton Football Club (claptonfc.com)

16. Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate & Cheriton Herald – Saturday 13 April 1918, p.8.

17. Northampton Mercury – Friday 12 April 1918, p.7.

18. Guardian article dated 7 November 2020:Historian finds clues to grave of Britain’s first black army officer | First world war | The Guardian

Other Sources and books of interest:

Brazier, Roy, Tottenham Hotspur Football Club 1882-1952, Tempus, Stroud, 2000, p.38.

Harris, Clive and Whippy, Julian, The Greater Game: Sporting Icons Who Fell in the Great War, Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2008, pp.177-8.

Jacobs, Norman, Vivian Woodward: Football’s Gentleman, Tempus, Stroud, 2005.

Middlebrook, Martin, The Kaiser’s Battle, Penguin, London, 2000.

Rawson, Andrew, Somme Offensive: March 1918, Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2018.

Vasili, Phil,Walter Tull, 1888-1918 Officer, Footballer: All the guns in France couldn’t wake me, Raw Press,Mitcham, 2010.

Wagstaffe-Simmons, G., Tottenham Hotspur Football Club: Its Birth and Progress 1882-1946, Tottenham Hotspur Football & Athletic Company, London, 1947.

Walter Tull Profile & Career Statistics (tottenhamhotspur.com)