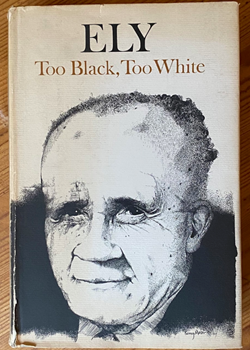

'Too Black, Too White' by Ely Green

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- 'Too Black, Too White' by Ely Green

‘Too Black, Too White’ is the fascinating autobiography of a smart, orphaned, unschooled boy of mixed ethnicity born in the southern US town of Sewanee, Tennessee in 1894. The son of white boy from a well-off family of German heritage and his black mother, a young maid, Ely was raised by a succession of African-American adoptive parents, These included an uncle, a grandfather figure and other guardians before being taken in by a wealthy white family in Waxahachie, Texas in his mid-teens.

Ely Green - pronounced ‘Ely’ as in ‘Ely Cathedral’ - is our protagonist - he is bright but understandably aggrieved at how his colour (when it is apparent) can have some dire consequences.

He is a quiet agitator for change whilst finding his own way through hard work and a kind, honest manner. He is later an agitator for the rights of the black man (and woman). On several occasions in his teens, twenties, thirties and forties he only just escaped with his life either being ‘mobbed’ by mean, always poor, resentful whites, about to be lynched or simply murdered, not least by the Ku Klux Klan.

Twice Ely has to be ‘got out of town’ in haste for his own good or ended up dead in the road or tortured then strung up from a tree. This is how he finds himself running from his home town of Sewanee as a young adult to find work and live in Waxahachie,Texas and then seven years later enlisting to serve with the American Expeditionary Force in France during the First World War.

During the First World War he twice risked the possibility of execution by the American Army in France for either inciting a mutiny amongst his fellow stevedores in St.Nazaire (he was their sergeant). He had in fact been trying his damndest to stop the strike, not lead it, and for striking a white Officer - something he refused to deny.

He never attended school but through his own desire he was able to learn to read and write, and adapt, resist. He was brought up in Episcopalian Church and had his own innate sense of right and wrong. Along the way he gained the respect and love of others despite attracting trouble at every turn.

He talked of traveling what he called ‘the third path of segregation as a ‘mulatto’ - he was neither black, nor white, though he could chose to pass as either. On census returns at the time, the terms ‘negro’, ‘mulatto’ and even ‘quadroon’ were used to differentiate between degrees of African-American ethnicity. Being of African descent, with any trace of black blood at all, you were treated by the white population - especially by the poor white in the south, as living ‘outside the written law’. Ely describes this as ‘the tyranny of man over man’ and a constant reminder of how his grandfather (on his mother’s side) had been ‘sold on the block’. Ely’s view is that the term ‘negro’, and all its derivatives, are used to ensure that black people ‘know their place’ which for a boy growing up means that he could never be considered a ‘man’.

Sewanee society was split three ways between the wealthy white population, the compliant African-American population (who could be middle-class small business and farm owners as well as poorer domestics and workers) and poor whites. Those who understood how segregation worked across these economic, cultural and racial divides could co-exist, however, this harmony was easily disrupted should anyone cross the line. This is the time of the ‘law of the south’ which allowed a white person to treat a black person as they wished.

His boyhood dreams were doomed because as a kid with black blood in him could not attend school - that was for white kids only. Yet he longed to go to school, just as he longed to become a cadet.

Ely wanted to be judged not because of colour of his skin, but because of his deeds: his industrious hard work and his focus when learning any new task weather raking leaves, shoe-shining, collecting herbal remedies and wild foods, hunting animals for their skins, training hunting dogs, shooting a pistol or rifle, saving and later lending money, training to be a boxer and then car mechanic and learning to read and write. He was exceedingly enterprising in any job, being fastidious and abstemious and quickly making himself indispensable to whomsoever he finds himself working.

It is the struggle against the fairness of the world that is his motivation and what constantly leads to confrontation and his near demise. In his mid teens he realises that if treated as a ‘nigger’ then he will always either be a ‘boy’ and when much old an ‘Uncle Sam’. It is during a confrontation, during which a group of white men when out hunting want to take Ely’s catch that he pulls a gun and has to quickly leave the town and state.

The most well-off white families were eager to have the best-looking African-American servants and Ely being blessed with matinee idol looks was such a find.

It is while working in a gang paving new roads in Waxahachie, Texas that he caught the eye of local businessman Judge Oscar Dunlap who picked Ely out to work directly for him. Good looking, courteous and an able listener, Ely was soon all but adopted by the ‘Judge’ and the Judge’s wife whom Ely called ‘Mother’ and daughter Ella.Though a generously paid servant-cum-chauffeur and bank courrier Ely was increasingly treated more like the family's youngest child and was even known as ‘Ely Dunlap’ to strangers. It is when working for the Judge that Ely gets an education of sorts: every day Ely has to find five words to put to the Judge for discussion and to improve his English and his handwriting Ely is told to keep a diary which he then keeps up for life and forms that basis for this extraordinary account ‘Too Black, Too White’.

With the First World War, Ely believed that by representing the American flag, working for the American government on foreign soil and that therefore on his return he would have to be accepted as a man and that this would take him beyond the ‘white man's law of the South’.

Ely would say, “I am going to fight to change the statute of law of the United States government, to abolish the word 'negro', which is the name of a slave. This is why I have to go to France, when I come back I will be an American citizen. No one can represent the United States on foreign soil but a man. I will be a man.”

He felt that it would be better to die in France a man then in the US as a ‘nigger’ (sic) “I'm going to France to fight for democracy”, he says, “This is the only way we can gain our respect as men.”

What followed was 18 months in France in what he calls ‘The Hellhole of Hatred’.

On 2nd of March 1918 Ely left the service of the Dunlap's. The Judge pulled strings to keep Ely in the U.S. When Ely found a way to get to France the Judge was still able to ensure that Ely did not join a combat unit. As a result Ely found himself a stevedore in St.Nazaire unloading and loading ships day and night.

|

||

|

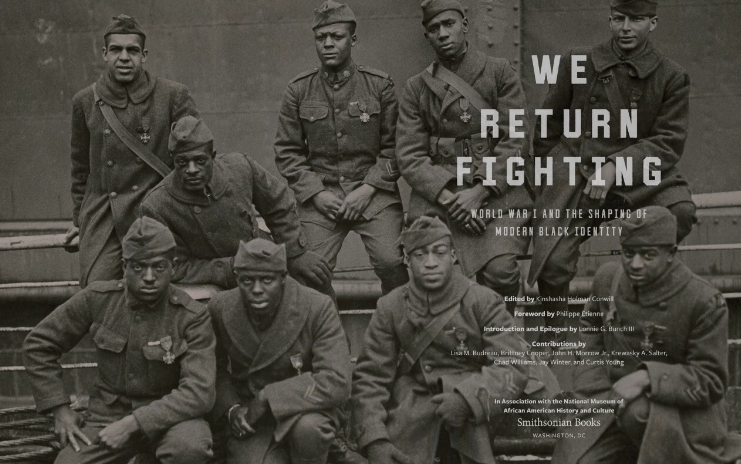

Front cover ‘We Return Fighting’ featuring soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment (Harlem Hellfighters) proudly wearing the Croix de Guerre. |

|

|

||

|

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Stamp Counter’. Army Y.M.C.A. Building №1, Camp Travis, Texas.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 13, 2020. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-08c7-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 |

|

![Photograph of Wright Cuney Price (left) and two other men. [Three World War I Veterans in Uniform], photograph, Date Unknown; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth246590/: accessed February 13, 2020), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Price Johnson Family Collection.](/media/13597/screenshot-2021-01-01-at-164235.png?width=300&height=473)

Ely was made a Sergeant and put in charge of a group of men. He worked them hard, treated them fairly, saved them collectively from potential court martial and long term imprisonment and saved one man from a court martial and potential execution having been accused falsely of striking a white officer.

Always keen to learn from others, Ely listens to the German prisoners working on the docks who explain that there might be a negro in America, but never in France where they had no such word for a slave. This is confirmed by French Senegalese soldiers who face their own battles with white supremacists in the AEF.

|

|

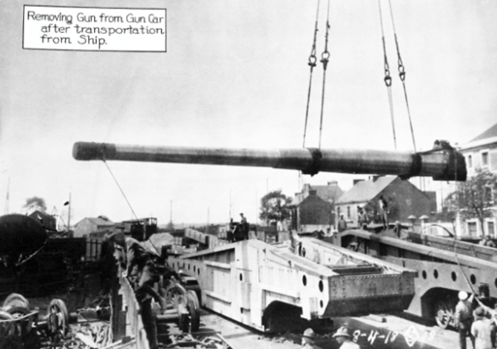

New Mexico-class battleship USS Mississippi (BB-41) at anchor, 27-12-1918.[5310 × 3951] |

The work held considerable risk, not simply from being poorly equipped for bad weather, being poorly fed and expected to do 15 hour shifts often through the night. One man, Sergeant Daniel was ‘split in two by a hatch’ when working to unload 16-inch guns from the battleship, Mississippi while a white NCO, Sergeant Farell shot African-American Charlie May Easter for taking a piece of bread after he had missed his shift in the canteen.

In due course Sgt Ely Green was court-martialed himself for punching Lieutenant Mooney who called Ely a ‘nigger’. Promptly locked up, some had hoped to bump Ely off as quickly as possible but word got to the Colonel and he was released. Ely was even offered a commission but turned it down.

The hatred felt for the white Americans by the French was so great that when riots broke out and some white soldiers of the AEF were murdered and for their safety, for the only time ever during the war, black and white marched together to protect the ‘Blancos’.

Ely was finally discharged on 4 August 1919. He was adamant that he would not be labeled a Negro Soldier when picking up his papers and so was possibly the only African-American solider of First World War to be known as an ‘American Soldier of the Texas battalion’.

As a veteran of World War One ‘and a patriot of America that has shed blood for his country’, Ely expected to be able to defend ‘his respect as a citizen’ but right there on the train across the States back to Texas in 1919 he found discrimination when the girls working for the Red Cross refused to serve hot chocolate and biscuits to any of the ‘Negro’ soldiers.

Ely continued to put his life in danger, in one instance preventing white cops from raping three black teachers which meant to save his own skin he could no longer work in Texas and he moved to California. Come the Second World War, and having a name for himself, the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, picked Ely out to go in and tackle the unions in the plane manufacturing plants where discrimination was preventing any black person from doing anything but the most menial of tasks.

Ely Green’s ‘Too Black, Too White’ is out of print, but often cited for the rare first hand account it gives of an African-American, albeit of mixed ethnicity, growing up in Tennessee and Texas and serving in the First World War. The story of the AEF is often told and that of the African-American combat troops who served with the French, but little is said of how brutally the AEF's own men were treated by their white officers because the American Army should be suitably ashamed of what took place.

Also see Mentioned in Dispatches Ep. 133 'African American Servicemen during WW1' with Dr Amanda Nagel'

Further Reading >

Freedom Struggles - African Americans in World War One (2011) Adrian Lentz-Smith

Glenda Gilmore (2009) Defining Dixie. Post World War One to the 1950s.

Emmett J Scott (1919) ‘The American Negro in The World War’.

Tyler Stovall : (1997) Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light.

Chad Williams (2010) Torchbearers of Democracy, African American Soldiers in World War 1 Era.

There’s no scientific basis for race - it’s a made-up label > National Geographic

Negro, Black, Black African, Black Caribbean, African American or What ? Labelling Black African population > BMJ

Negro not allowed on Federal Forms. White House to Decide. (2017) > NPR

Race and the American Census. Mulatto, Quadroon, Octoroon … (2015) > NPR

African American Soldiers hoped their service after World War I would secure their rights at home. It didn’t.

A Brief Look at African Americans in World War I > National Archives

We Return Fighting : World War One and the shaping of Modern Black Identify edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill