Edward Allen Wood

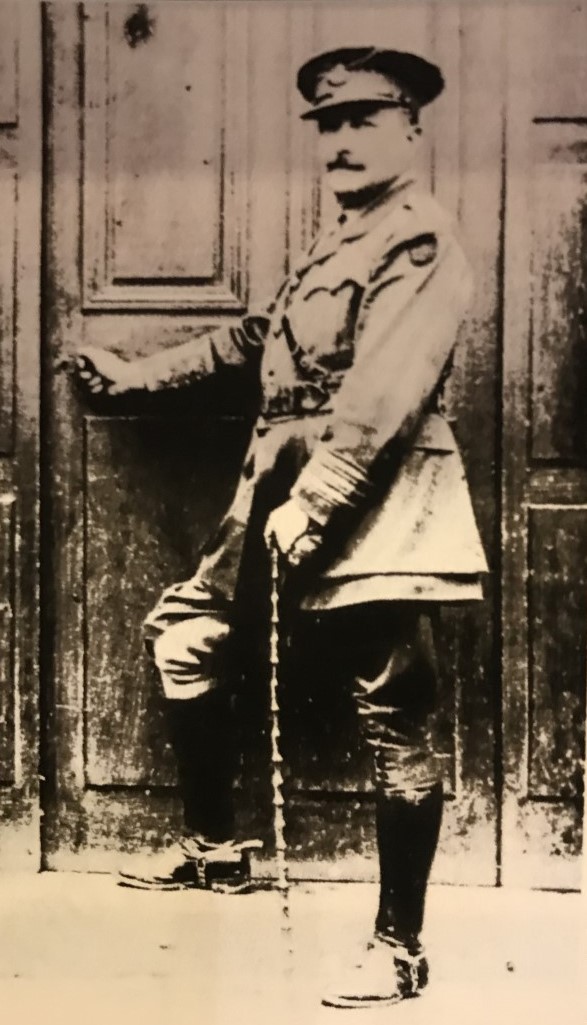

Despite his unmilitary appearance, short, stout and with a boozer’s complexion, Edward Allan Wood was a warrior. He was also a liar, a fantasist and an embezzler. He was good at war and was fulfilled by its challenges. He commanded 55th Brigade in the elite 18th (Eastern) Division for almost a year in heavy fighting, won four DSOs, claimed to have been recommended for the Victoria Cross twice, was wounded five times, gassed twice, buried once and mentioned in despatches seven times. Few would have predicted such a career when the war began. Few would have predicted any career at all. Wood was 49 and his official military status was ‘Captain, Retired, British South Africa Police’. His journey to this point was typical of a tangled life.

Wood was born in India, the ninth son of Oswald Wood, a civil servant who later became a judge. Money was scarce in such a large family. Financial difficulties prevented Wood from entering Sandhurst or even from accepting a commission in the field from the Commander-in-Chief India, Field-Marshal Lord Roberts. Instead, he joined the army as a private soldier, enlisting in the 2nd Dragoon Guards, then transferring to the 17th Lancers. He later served as an officer in the Bechuanaland Border Police, the Matabeleland Mounted Police and the British South Africa Police.

He took part in the Jameson Raid, where he was captured, and in the South African War. His whereabouts between his resignation from the BSAP on 16 March 1906 and the outbreak of the European War are obscure, but in 1914 he was in England and immediately offered himself for military service, becoming a company commander in 6th Battalion King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. He gave his age as 42. It is doubtful whether a 49-year old would have been accepted as a company commander, even in 1914.

Wood immediately prospered in the army. He commanded 6th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1917, winning the first two of his DSOs. He was promoted GOC 55th Brigade on 9 November 1917, commanding it until he went sick on 24 October 1918.

Warriors are not always appreciated by their men, especially in an army as deeply civilian as that raised by Lord Kitchener. Wood was an exception. He was an inspiring figure. One of his soldiers, Private Robert Cude (7th Buffs), declared that he would ‘serve in Hell, so long as General Wood was in command of the Brigade’. One of a commander’s most difficult tasks is to rally broken troops. Wood did this at a vital moment of the German spring offensive, near Monument Farm, re-organising three companies of 7th Queen’s after they had been caught in an intense enemy barrage while forming up for an important counter-attack. Not only did Wood prevent the formation from disintegrating, he also succeeded in getting it to move forward. His extraordinary career perhaps culminated on 20 September 1918 when, alone and unarmed, he captured more than twenty Germans by pelting them with lumps of chalk and old boots!

Wood’s post-war career, however, was a sad diminuendo. There was no place for him in the post-war army. His had only been a temporary commission. This contrasted with Wood’s own view of himself, in which he was firmly convinced that he was a British cavalry officer and gentleman. His Who’s Who entry deliberately contrives this impression, an impression he sought to confirm even beyond the grave. He succeeded in having himself described on his death certificate as ‘Brig. General C.M.G. 17th Lancers (retired)’. He found a temporary harbour commanding a formation of Black and Tans, where he succeeded Frank Crozier, but after the formation of the Irish Free State his life went steadily downhill.

He spent most of his remaining years in a fruitless war of attrition with the British government, trying to obtain an officer’s pension to which he had no claim. During the process he managed to alienate everyone who tried to help him, including King George V. Monies given to him in good faith had a habit of disappearing or of being used for purposes for which they were not intended. He eventually went bankrupt after trying to set up a bridge club.

His personal file in The National Archives is full of letters from south coast landladies petitioning the War Office for the address of Brigadier-General Wood who had left without paying his bill. Edward Allan Wood died 20 May 1930 from cirrhosis of the liver aged 65 (army age 58).