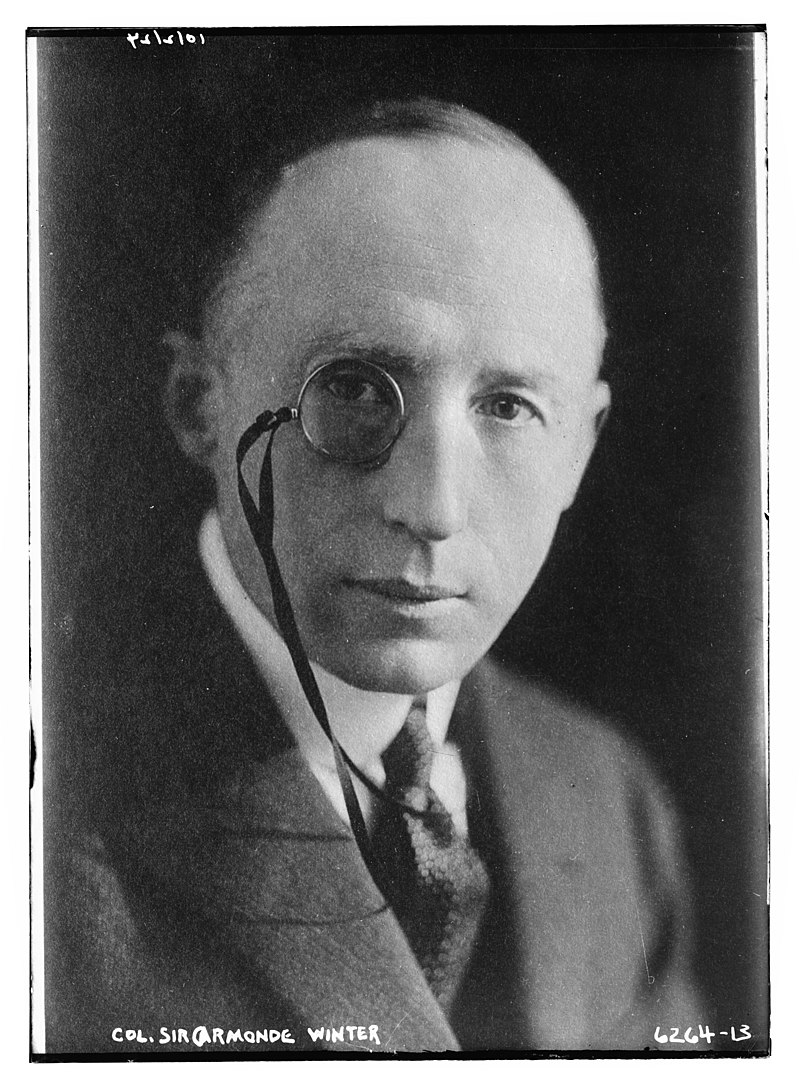

Ormond de l'Epee Winter

Ormond de l’Epée Winter was born in Chiswick, the son of W H Winter, Controller of Stores at the General Post Office. He seems to have inherited the scientific bent of his uncle, Chief Engineer to the Madras Railway and a well-known inventor, retaining throughout his long life a restless intelligence and a fascination with all things scientific. Winter was commissioned in the Royal Horse & Royal Field Artillery on 17 November 1894. He spent virtually the whole of his pre-war career in India. His outstanding ability to trade, ride and back horses, together with prudent resort to Indian money lenders, allowed him to enjoy a standard of living greatly beyond that of his pay and meagre allowance from his father, with whom he had quarrelled. Winter had an ability bordering on genius to irritate senior officers. This almost certainly cost him his place at the Staff College, Quetta. His temperament also regularly got him into scrapes.

During a brief period at home, in 1903, while cramming for the Staff College entrance examination he defended himself against a youth who had been throwing stones at his boat by hitting him with a scull. The youth died. Winter was tried and acquitted of manslaughter. General Sir Edmund Barrow’s description of Winter in his 1912 Annual Confidential Report as ‘a smart and talented officer, excels as a horseman, a horse-master and a Vet, per contra is not at all times reliable in some respects’ seems about right. Winter typically took violent objection to the report and expended a huge amount of effort over the period of a year successfully having the ‘adverse’ comments expunged from his record. Equally typically, he described this success as ‘probably the one and only real achievement of my career’.

When the war broke out Winter was on leave in Scotland from his post as OC 10th Battery Royal Field Artillery. Despite his best efforts, and accompanied by some ill-luck, he failed to obtain a transfer to the BEF and was compelled to return to India. When he did take his unit to war it was on Gallipoli as part of 11th (Northern) Division. From 12 October until 28 December 1915 he was GSO2 13th (Western) Division, a position he did not much enjoy, frustrated by the lack of action and the overpowering ‘hands-on’ approach of the divisional commander, Stanley Maude. When 11th Division was re-deployed to the Western Front in 1916 Winter went with it.

He spent 1916 and 1917 in command of 48th Brigade RFA, whose duties he described as among the ‘most interesting’ of the war. They certainly gave him scope for his love of action. Winter was a warrior. Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Hutton described him as ‘the bravest man I have ever known, he really seemed to enjoy war .. In attack he usually arrived on the final objective before his FOO [Forward Observation Officer] and on one occasion is reported to have led an infantry attack ... mounted on his horse. Sometimes his brigade HQ was to be found practically in the front line, but there was always an excellent meal and a bottle of wine [accompanied by] Rabelaisian anecdotes. His attitude to his superiors was .. fearless and on one occasion he obtained the cancellation .. [of an] attack on uncut wire by refusing to fire his guns in support ... hence perhaps his failure to secure high promotion .’

Nevertheless, Winter did secure promotion to brigadier-general when he succeeded his able and long-suffering superior, J W F Lamont, as CRA 11th Division on Boxing Day 1917. He commanded the guns of 11th Division for the rest of the war, except for a short but important period when he commanded the division itself while its GOC, H R Davies, was recovering from a wound. Winter’s period as a temporary divisional commander embraced the crossing of the Canal du Nord and the capture of Cambrai. He commanded the division with complete self-confidence and authority, ignoring criticisms from the Second Army staff that his HQ was too far forward, a view not shared by his corps commander, Sir Arthur Currie.

During the war Winter had risen from a getting-on-for-elderly major to a youthful acting major-general. When the war ended he was all too aware that there were many officers in his position. He avoided the tedium of the post-war army by acceding to Sir Hugh Tudor’s request that he should become Chief of the Combined Intelligence Services at Dublin.

Winter played a leading part in the ‘dirty war’ against Sinn Fein and the IRA, a war he was able to reflect upon in tranquillity with a degree of objectivity. He retired from the army in 1924. He was a staunch anti-Bolshevik and was a member of the pre-Mosley British Fascists. In 1940 he joined the Finnish forces in the Winter War against the Soviet Union. He was 65.

Winter described his tastes as ‘cosmopolitan’. He was a bon viveur, with an expert knowledge of French and other cuisine. He spoke French, Russian and Urdu. He was a remarkable veterinary surgeon with a sophisticated knowledge of biology. His marriage, contracted at the age of 52, seems to have been a very happy one. He wrote with commendable clarity. His autobiography, Winter’s Tale (1955), is a remarkably revealing and extraordinary account of an unusual life. He was knighted in 1922.