1917: Right Story, Wrong Location

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 1917: Right Story, Wrong Location

The following piece, by military historian Andrew Rawson discusses the location implied in the new film '1917'.

I am no fan of the majority of modern World War I films, because errors and inconsistencies with the facts irritate me. However, they do bring pleasure to a great many and even introduce new people to this important period of history. I am not into arguing over the minor details about the wrong season, or the incorrect piece of equipment, but I do find myself looking up the sources to see where the story came from; if only from the screen writer’s head. With the help of the internet and my own research, carried out over the years, makes this possible without too much trouble.

The new film, 1917, which is out on 10 January in the United Kingdom, has had me puzzled. I have not seen it, yet I have seen enough trailers and clips to get a rough idea what the story is. Two young soldiers “have to cross into enemy lines on a race against time to deliver a message that will save 1600 lives.” The Wikipedia entry goes further, stating that the story takes place ‘during one of the skirmishes soon after the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line.’

The director, Samuel Mendes, has stated that the film is inspired by a story told to him by his grandfather, when he was a boy. He actually says “It lodged with me as a child, this story or this fragment, and obviously I’ve enlarged it and changed it significantly. But it has that at its core.” So, I wanted to know about the story and how it had been changed.

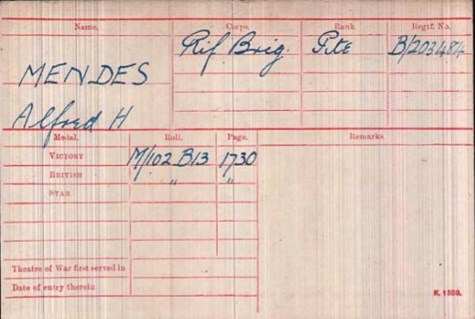

Above: Alfred Mendes (the grandfather of film director Sam Mendes).

Alfred Mendes’ autobiography was published by the University of West Indies Press in 2002 and copyrighted by the editor Michèle Levy.[1] You can find it on Google books and while parts are unavailable (because the publisher want you to buy the full copy) the relevant World War I section can be read.

Alfred was born in Trinidad in 1897 but he went to Hitchin Grammar School in England in 1912.

Above: Hitchin Boys Grammar School, c 1955 (Image courtesy of The Francis Frith Collection - www.francisfrith.com)

He returned home in 1915, only to join the Merchants Contingents of Trinidad, young men wishing to serve in the war, and sailed back to England. Two years with the 1st Rifle Brigade followed and while there is no mention of any heroic actions near the Hindenburg Line in the spring of 1917, there is a long section about one in the Ypres Salient during the Third Ypres campaign.

Above: The medal index card for Alfred Mendes ((c) The Western Front Association / Ancestry).

The 4th Division struggled in the ‘vast sea of malignant mud and water’ north of Poelcapelle on 12 October, officially called the First Battle of Passchendaele. Mendes made a name for himself during a second attempt to advance the following day.

Above: Assault on Passchendaele 12 October - 6 November: A line of infantry marching along a muddy corduroy track strewn with debris at Westhoek. © IWM (E(AUS) 1222)

The Rifle Brigade cleared part of the village the following morning. Battalion headquarters, which was based at Ferndon House, then ordered Captain Craigmile to hold off any counter-attacks. Craigmile was also instructed to report back on all four companies of the 1st Rifle Brigade, a task for which Mendes volunteered.

Mendes found the other three companies in the maze of shell holes, while under sniper, rifle and machine gun fire. He even took ten prisoners and sent them back up the line without an escort. After a day of ‘wandering around in circles in No Man’s Land’, the intrepid messenger reported back. Craigmile was awarded the Military Cross and Mendes the Military Medal. As Mendes’ citation states, ‘it was largely due to his coolness and his complete disregard for his personal safety that his commanding officer was kept informed of the state of affairs on that important flank. His activity and untiring energy under the worst possible ground conditions and weather was remarkable.’

Above: The Military Medal

Craigmile was killed in action alongside Mendes in March 1918, fighting off the attack known as Operation MARS, east of Arras. He was buried in Fampoux British Cemetery.

Above: Fampoux British Cemetery Image courtesy of www.ww1cemeteries.com

Mendes went on to take part in 4th Division’s actions along the La Bassée Canal, following the breakthrough on the Lys on 9 April. He was evacuated suffering from gas, towards the end of the campaign.

So, there we have it the characters, the plot and the location. An article in the Sun back in August 2019 has the film set during the battle for Passchendaele, as does one or two other film reports published around the same time. Yet the scene where General Erinmore issues the order to take a message to a battalion about to be annihilated mentions a huge, new defensive line. The general also mentions Croisilles and Ecoust, both outpost villages close to the Hindenburg Line, south-east of Arras.

So, that begs the question why change a perfectly sound story of heroism set in the Flanders mud in October 1917 to a different time and place? The film has been praised for using a camera technique called a ‘one continuous shot.’ Or rather a series of shots edited to make it appear as one shot. The reasons behind this are far too technical and arty for me to comprehend. But it fits with the storyline, which involved a runner getting a message across the battlefield.

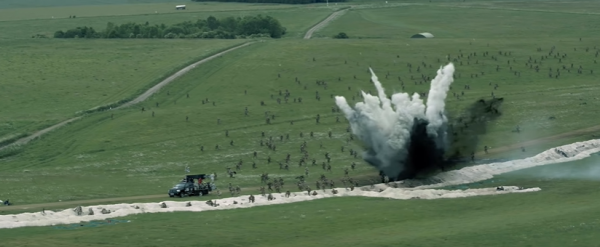

Maybe, the cost (the film was budgeted at $90 million) decided the choice. After all it would be far cheaper to create the ‘scorched earth’ terrain created by the Germans as they fell back to the Hindenburg Line. Imagine the costs of reproducing the muddy moonscape which was found in the Ypres Salient in October 1917. It would have been a pretty dreary back drop compared to the one I have seen on the trailer.

Go and see the film and make your own mind up. Enjoy the story and maybe pick out a few faults. Alfred Mendes certainly was a brave man and he helped keep his battalion safe around Poelcapelle in October 1917. However, he did not run a marathon across the Somme’s chalky downs in March 1917.

Andrew Rawson

[1] ISBN 976-640-117-9