1940: The 1990 Presidential Address delivered by the Honorary President John Terraine

I have always regarded this occasion — our Founder's Day — as the time to speak on one of the larger themes of war. In recent years, as we passed through the seventieth anniversaries of the First World War, I have taken the years one by one and attempted an analysis of each one — the point being to detect the differences between them, and thereby assess the progress of the war.

Today I am going to talk about a fiftieth anniversary — of the year 1940. To see and read the outpourings of the media, you might suppose that the only thing that happened in 1940 was the Battle of Britain — but that is the media for you. The truth is that it was a year of three profoundly important battles; their very names reveal the scale of their importance: the Battle of France, the Battle of Britain, the Battle of the Atlantic. And they were, as one can now easily see, intimately connected with each other.

The Battle of France was, of course, the first Western Front of World War II. I expect most of you share my feelings when I read about it — feelings of meeting with familiar ghosts, with hosts of unquiet dead who believed they had done a job and finished it, only to have their sons treading the very same roads to meet the same enemy. You look at the campaign maps of 1940 and what are the place-names that you see?

Amiens, Arras, Vimy, Bethune, La Bassee, Hazebrouck, Cassel, Ypres — and the rest. The difference — the terrible difference — is that from 1914 to 1918 the Front held. It groaned at times, but it never gave way. In 1940 it gave way at once; the Allies were absolutely defeated in six weeks — and as a result a second Western Front had to be created in 1944 by means of the most elaborate, most complex and most hazardous operation of war in history. And that time it was the enemy who was defeated.

For the great British public, however, attention has always chiefly focused on the Battle of Britain. There is, I would agree, some excuse: war on or over British soil was a distinctly unfamiliar experience — it was likely to stick in men's minds. Furthermore, the battle had unmistakable epic quality. So the picture has been firmly drawn: the great German bomber fleets in their orderly formations crossing the Channel under the unwinking eyes of the Chain Home radar stations, with their escorting fighters above and around them, to encounter the RAF's Fighter Command in a very combative frame of mind indeed, and firmly guided by the Dowding system. It is one of the most impressive scenes of war of all time.

The key element in it, let me say at once, is the fighters — not the menacing bombers, pushing along at about 250 mph, whose mission was nothing less than to knock Britain out of the war once and for all — but the fighters, by which I mean the Luftwaffe's Messerschmitt 109 BF, the single-engine high-performance fighters which had made their first operational appearance in Spain in March 1937. In 1940, flying from bases in the Pas-de-Calais, the Me 109s could operate over South-East England for twenty minutes, providing they did not have to zigzag too much in protecting the bombers on the way. Until the Germans had won the Battle of France, they did not possess bases in the Pas-de-Calais. Until then, any attempt at an air attack on Britain would have been a totally different matter from what we saw from July to October of that year. The probability is that undefended bombers would have passed immediately to night operations, which is something to ponder.

The received image of the Battle of France is quite different. The dominant element in this picture is the ten Panzer divisions — 2574 tanks — which spearheaded the swift march of the German armies through Holland, Belgium and Northern France. Every day newspaper readers could see the thick black arrows which showed the German advance plunging across the maps towards Paris and towards the Channel. Newsreels provided close-ups of the reality: the grim, business-like German tanks with their deadly-looking guns and their black crosses, tight-lipped, hard-faced senior officers and cheerful young Nazi crewmen with a lot to be cheerful about. One received also a sense of there being a lot of German aircraft in the sky, but the only ones that really impinged on the public consciousness were the Stukas, the terrifying Junkers 87 dive-bombers.

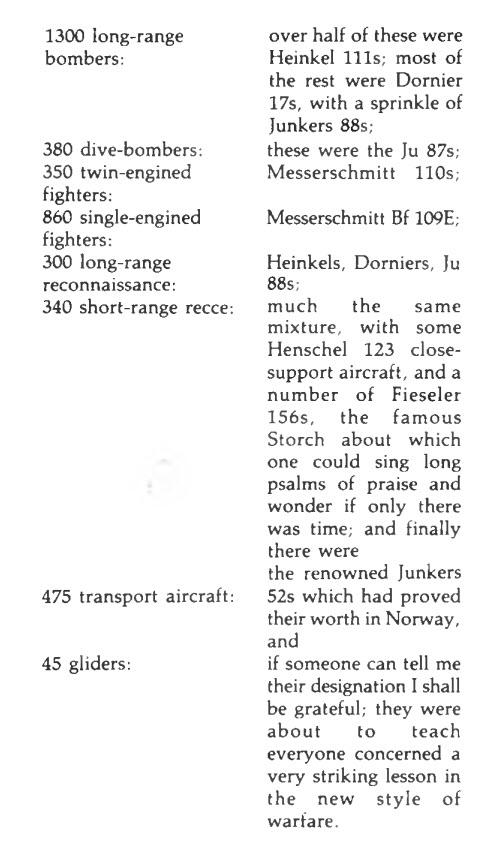

Stukas and Panzers: the two together, in France as in Poland in 1939, composed the Blitzkrieg — and the Blitzkrieg, in 1940, was just another name for the invincible military might of Nazi Germany. Certain things escaped notice in the shock and bewilderment of the German onslaught. It is not surprising; the brutal violence and speed of the thing, once properly off the mark, threw just about everyone off balance. One quickly forgot, for instance, that the Blitzkrieg, as I have just described it, was not the first manifestation of the battle. The battle opened on 10 May; the Blitzkrieg really started on 13 May, when the main body of the German armour burst out of the Ardennes and rolled down to the Meuse. The way had been prepared for it. At this point I think I had better give you an idea of what went before (and above) the German armour, pouring in dense, vulnerable columns through the narrow passes of what has often been called the little Switzerland'. The German Air Force deployed, for the attack in the West in May 1940, the following types and numbers:

The total is 4050 aircraft. That is an establishment total; the operational figure is somewhat less, but not much, since this was the beginning of a campaign, following a long rest.

In the early hours of 10 May, virtually the whole lot were on the move. It was still dark when the bomber crews, without any warning, were hauled out of their beds and, says Alistair Horne, 'ordered to attend briefings at fifteen minutes notice. There was no time even to shave. Shortly before sunrise, every available aircraft left its field.' The German long-range bombers had a full programme that day. The first bombs began to drop at about 4.30 am European time. The first violence fell mainly on the two neutrals, Holland and Belgium, and it was there that the 'new style' was first seen. The Heinkels and Dorniers ranged out over the North Sea, mine-laying off the Dutch coast, the streets of The Hague were machine-gunned, airfields were attacked and half the Dutch Air Force (only 125 planes) wiped out on that day. The special feature was the use of airborne troops to capture key localities, mostly in uniform, but some of them disguised (this was when the image of the nuns with tommy-guns hidden in their habits became familiar). The world discovered that, apart from their tactical usefulness, paratroops could produce a moral effect out of all proportion to their numbers when they enjoyed all the advantages of surprise. It would be a year before the other side of that picture was revealed.

In Belgium the story was the same — a weak air force immediately shattered, an unprepared nation virtually helpless. The sense of helplessness was what counted most, and nothing contributed more to that than the capture of the Belgian Fort Eben Emael (regarded as the 1940 equivalent of Verdun in 1916) captured in a few hours at a cost of six German dead and fifteen wounded, as a result of an airborne assault in which the gliders were landed 'plumb on top of the fort' itself.

10 May was one long 'Shock Horror Mystery Sensation', and believe me, it did not confine itself to Holland and Belgium. The bombers reached down to the Channel coast; fifty French airfields were attacked; railway centres and road communications were attacked deep into France. This was of the essence; this was the accompaniment of the whole battle until the British flight and the French surrender. It was this deep bombing which, in the words of John Williams: 'wrecked communications, isolated command-posts and individual units, and left the various formation headquarters ignorant of what was happening in the forward zones, and unable to check information and exercise any control.' We may add that it also inhibited or actually prevented movement on the ground. By bombing villages and towns on the lines of communication the German bombers filled the streets with rubble, thus making impossible the quick reinforcement and supply of the front forces. Constantly we hear of the French running out of ammunition — this was why.

And once more there was a moral factor involved, which is incalculable but evidently of very high importance. Patrick Turnbull, who experienced it and wrote it down in 1978, says this: 'Whatever statistics may be produced, it is safe to say that every soldier, British, French or Belgian, would be as prepared to swear today as close on forty years ago that his every pace was harried by swarming Stukas, Junkers, Heinkels and Dornier flying pencils', and that from dawn to dusk he witnessed the depressing spectacle of enemy bombers cruising undisturbed in large formations, attacking troops on the move and defensive positions, and destroying every city, town or village for miles around with impunity. That was it: 'enemy bombers cruising undisturbed in large formations'.

We are looking at a very remarkable bomber performance (too often disregarded). It was a variation on what, in 1944, when the pendulum of war swung over, would be called interdiction', meaning the isolation of a whole battle area to prohibit reinforcement or retreat or supply. In 1940 it also meant the isolation of separate parts of the battlefield from each other so that the Battle of France takes on the appearance of a whole complex of separate battles, fought without cohesion and without effective control by any central Allied Command — a dreadful picture. How was it done?

To answer that question, we have to ask another: what could have prevented it? It takes no crystal ball or penetrative genius to reply to that: a powerful Allied fighter force could have prevented it, resolutely and correctly handled. The simple, terrible truth of the Battle of France is that the Allies did not have a powerful fighter force. The French Air Force had some 790 operational fighters, but that figure only illustrates once more the foolishness of playing games with numbers; 'operational' — en ligne in French parlance — only meant that the aircraft was ready and equipped to take off from an airfield, it did not mean modern', i.e. one built within the last two years. The standard French fighter (equipping nineteen out of twenty-six combat-ready groups) was the Morane Saulnier 406, underpowered and under-gunned. There were never anything like enough French fighters able to take on the Messerschmitt 109s. No more need be said.

The RAF's direct contribution to Allied air power took two forms: the Advanced Air Striking Force, basically a light bomber formation — part of Bomber Command — whose main constituent was the RAF's outstanding failure of the war, the Fairey Battle. The AASF also contained a fighter wing, three squadrons equipped with Hawker Hurricanes. There was also the RAF Component of the BEF, operating under Army direction, consisting of four long-range reconnaissance squadrons (Blenheims), five tactical reconnaissance squadrons (Westland Lysanders) and four more Hurricane squadrons. There, too, you have your answer to the question, 'what could have prevented it?' For those seven Hurricane squadrons (ultimately to be increased to the equivalent of sixteen) were something special. I said in 'The Right of the Line': The Hurricane pilots, and they alone of the Allies, had the satisfaction of meeting the enemy with entirely adequate equipment and the ability to use it. Seven squadrons, at full establishment, means 112 aircraft; sixteen squadrons means 256.

But never, at any time, were the Hurricane squadrons at full establishment — mostly they were at about one-third strength. So what happened was exactly what one might expect. The German fighters, over 1200 of them, but above all the Me 109s, ruled the sky, and in doing so they achieved, for the first time against a major enemy, the saturation of a battle area by air power, and that was what won the Battle of France. It was, in fact, won in six days. The Panzers reached the Meuse on 13 May; at once the chronic French shortage of anti-tank guns stood revealed. Yet the French possessed 11,000 pieces of artillery, and the prestige of their artillery arm was undoubted. But 13 May and the following day witnessed some awful scenes: now was the time of the Stukas, screaming down out of the sky on to the French gun positions, and the unthinkable spectacle was seen of the gunners abandoning their guns. Not just here and there, but along whole divisional sectors; as Alistair Horne says, 'There is no doubt that the real collapse began with the gunners.' And there is no doubt that the cause of this immediate and lasting demoralisation was the Stukas.

What makes that so ironic is that they were due to be phased out by the end of 1939 — it was the Polish campaign that reprieved them. And what doubles the irony is their evident vulnerability, both to fighters, as was seen over Britain in August, and to anti-aircraft fire. The effectiveness of this was amply demonstrated the next day, when the Fairey Battles were shot out of the sky, attempting to bomb the Meuse bridges. The main agent of their destruction was the German light flak', the 20mm and 37mm guns; Guy Chapman comments: The Germans did not waste their fighter pilots' strength in defence, but relied on their excellent anti-aircraft guns . . . ' Like the anti-tank guns, the French had neglected these, and now they rued the day; it would be a long time before these two lessons sank in in Britain.

It was to the accompaniment of a bombing crescendo that the climax came on 15 May. It was on that day — at 7.30 am — that the French Prime Minister, Reynaud, told Churchill: "We have been defeated . . . We have lost the battle.' At 11 am Holland surrendered. Rotterdam had been bombed; the Dutch gave out — and probably believed — that 30,000 people had been killed. We now know that the true figure was under 1000, but 78,000 people had been made homeless; confusion and panic reigned. It reigned also among the thousands of refugees pouring along the roads of Belgium and France, harried by machine gun fire and bombing all the way. It reigned in the French Ninth Army at Sedan; under the incessant hail of bombs from the Stukas the Ninth Army was breaking up. And all the time the German heavy bombers were hammering at the rear areas; half the French fighter force in the central sector was destroyed on the ground; communications virtually ceased to exist. Panic also seized the French High Command. There was no recovery from this.

Reynaud was right; the Allies had lost the battle. They had lost it to the achievement of complete air superiority by the German Air Force, enabling the Stukas to perform, the Panzers to roam where they willed; this was an achievement above all of the fighter arm, in particular of the Messerschmitt 109. This was what gave Germany victory in May and June 1940, a victory which transformed the war, all done by the saturation of the battle area by air power, as it would be again in reverse in 1944.

France surrendered on 22 June. I said in 'The Right of the Line': 'The fall of France was a catastrophe whose consequences can scarcely be measured.' So it was; it determined the future shape of the war; it could well have marked its termination. Down the years there has been much talk of the 'Miracle of Dunkirk'. The only real 'miracle' was the miraculous good fortune of

having a lunatic in supreme command of the enemy. You will be hearing more about that.

Meanwhile, as the month of June ended — a beautiful month of lovely summer days — Britain counted the cost of the first encounters with this enemy who had done more damage to us in less than a year than the Kaiser's armies had done in four-and-a-half years. Neither the Dunkirk evacuation nor the Battle of Britain which followed it were miracles, though it has pleased the

superstitious and the media to call them that. As Basil Collier, an Official Historian, has said: 'They were military events whose outcome was determined by military factors.' The governing military factor was that, while the Army had been allowed to fade away almost to nothing from its great strength in 1918, and both the Navy and the Royal Air Force had also dwindled to shadows of former power, the belated rearmament programmes of the very late Thirties had favoured the Navy and the Air Force to the extent that they, at any rate, were still able to influence events decisively.

We rejoiced that we were able to get the men away; we can still rejoice. But only for that reason: the men were saved — a total of 368,857 from the two evacuations, Dunkirk and Normandy. It is an impressive figure, but we should be clear about the reason for it. Basil Collier says: The British were able to get their troops away from Dunkirk because they had overwhelming naval superiority, enough ships and enough seamen to undertake the business at short notice, and the means of providing at least the bare minimum of air cover which seemed necessary to make the project feasible.

But large numbers of men wearing uniform, however high their courage, however firm their determination, are not an army. The BEF came home in 1940 with nothing but its personal weapons; it required re-equipment with everything from light machine guns to heavy artillery. All its guns had been lost — 2472 of them; all its tanks — but they only numbered about 300, under-gunned and underpowered, which was a national disgrace; 63,879 vehicles — all mechanised; they would be sorely missed; 20,548 motorcycles (very useful to the Germans); stores and equipment for half a million men — no doubt the Germans found a lot of that very useful too, and British war industry was already struggling in all departments. The campaign in France had cost the Army 77,365 casualties, 5688 of them killed in action or died of wounds, disease or injury; of the total loss, 2254 were officers, which was far more than a small, expanding army could afford. This figure includes 1536 officers taken prisoner; the total taken prisoner was 39,777. In the six weeks of the Battle of France the RAF lost well over 900 aircraft, and 1382 air and ground crew, of whom 915 were aircrew. In the Dunkirk evacuation the Royal Navy lost seventy-two vessels, including six destroyers, with another nineteen damaged. We shall see that this is a significant statistic.

Statistics, I am afraid, are an inevitable accompaniment of modern military history. What these particular statistics proclaim unmistakably is disaster, pure and simple. But fortunately, as Sir Basil Liddell Hart said, in June 1940, . . . the British people took little account of the hard facts of their situation. They were instinctively stubborn and strategically ignorant.' It was just as well that they were. Churchill, who became Prime Minister as the Battle of France was beginning, declared flatly: 'We shall never surrender.' These were proud words and they touched the deeps of the nation's pride. Churchill's option was 'no compromise' with the enemy, now in the full flush of his victory. Later this formula would be translated into 'Unconditional Surrender' by that enemy, but in 1940, as Liddell Hart remarks, 'The course of no compromise was equivalent to slow suicide.' Hitler would have agreed wholeheartedly with this thought; even before the war broke out he had told his military leaders that he believed Britain could be defeated by cutting her overseas supply lines. Soothed by this idea, and encouraged by the great successes of the German Air Force in Poland, in Norway and now, overwhelmingly, in north-west Europe, he was already thinking very positively about his cherished scheme of attacking the Soviet Union, in accordance with Nazi doctrine. But he allowed himself to be seduced by the siren voice of Hermann Goring, promising that the Luftwaffe would be able to give air cover to an invasion of Britain across the narrow seas.

No plan existed for such a thing, but one was improvised: SEELOWE, Operation SEALION. Everything in it would depend on the Luftwaffe being able to win air superiority over the Channel for long enough for the very weak German Navy to convoy an army across. The first obstacle, of course, would be the RAF's Fighter Command; and the Battle of Britain is the name for Fighter Command's response to the threat of German invasion on the pattern of the Battle of France: the army advancing, headed by Panzer divisions, behind a pulverizing air bombardment supplied by the German bomber force, and all escorted and protected once more by the German fighters.

But this time there were certain differences. Indeed, because of them I have called this a battle that began to be won several years before it actually happened. The story has many possible beginnings, but probably the right one is in November 1932 when Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin uttered his famous warning: 'I think it is well for the man in the street to realise that there is no power on earth that can prevent him from being bombed. Whatever people may tell him, the bomber will always get through.' This was the firm belief of the Air Staff and the RAF, but fortunately there were some who were not convinced. One of them was Mr A. P. Rowe, a scientist in the Air Ministry's Directorate of Supply and Research, who conducted a personal investigation of British air defence. His report was pretty ominous and it stirred his Director, Mr H. E. Wimperis, to press for a full-strength Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence, which was duly set up at the end of 1934 under Sir Henry Tizard. This was a landmark in military history.

All through the history of modern times, as science unfolded its wonders, a constant quest (like the dream of the alchemists in the Middle Ages) has been a 'death ray'. Sir Henry Tizard was far too good a scientist just to brush a thing like that aside. He consulted the Superintendent of the Radio Department of the National Physical Laboratory to see whether some sort of 'death ray' might be possible against attacking aircraft. This was a wonderfully productive enquiry, because the Superintendent in question was Mr Robert Watson-Watt, who not only put 'death rays' out for the count, but pointed out that even if such a thing did exist it would be useless unless its target could be accurately located. Location, said Watson-Watt, was the heart of the matter, and location by radio signals was a matter to which he had given some thought. Out of this perception was born radio-location, officially known as Radio Direction Finding (RDF) whose popular and famous name is Radar. When Watson-Watt was able, in February 1935, to demonstrate to the Air Member for Research and Development, Air Vice-Marshal H. C. T. Dowding, that Radar was a practical method of locating aircraft in flight; the winning of the Battle of Britain began. Dowding saw at once that the bomber might not always get through, and he made it his business to ensure that that should be so.

I like this story. It relates to a period when, reading the history of it, one might think that the British could no longer think straight or do anything right. But Watson-Watt thought straight, and when the first of what were called the Chain Home Radar stations was handed over to the RAF in 1937, we were definitely doing something right. And this was not the only good move that was developing. 1934 was the year when the Air Ministry issued Specification F5/34, the 'order form' for the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire, the all-metal, eight-gunned fighters powered by the Rolls-Royce PV-12 engine (the famous Merlin), which would match the high performance of the Messerschmitt 109.

For the RAF, this was a period of constant happenings. All through the late Thirties it was going through a succession of expansion schemes with all the troubles that they inevitably bring. It also underwent a fundamental reorganisation — the introduction of the functional Command system which brought into existence the famous Commands which fought the war — Fighter Command, Bomber Command and Coastal Command. In July 1940 Fighter Command numbered fifty-two squadrons, twenty-five of them equipped with Hurricanes, nineteen of them with Spitfires, two with Boulton-Paul Defiants (a sad failure) and six with adapted Bristol Blenheim light bombers — a desperate expedient. They were organised into four Groups: No. 11 in south-east England — the 'sharp end' of anti-invasion and anti-air attack operations — No. 12 in the Midlands, covering important industrial centres — these were the two strongest groups, with two weaker ones on the flanks — No. 10 in the south-west, and No. 13 for the north-east and Scotland. The Command counted 644 operational aircraft with 1259 pilots present for duty. It was none too strong for what it would have to do.

It did have, however, one unquantifiable asset: its Commander-in-Chief from the very beginning, 6 July 1936, Air Chief Marshal (as he now was) Hugh Caswell Tremenheere Dowding, nicknamed 'Stuffy', fifty-eight years old and looking about as unlike a fighter pilot or a fighter commander as you can get. Yet if any one man can be said to have 'won' such an event as the Battle of Britain, that man was Dowding. It was fought in accord with the Dowding System, which governed the operations of Fighter Command and to which the enemy was forced to conform. The Dowding System was the victor. At the root of it was communication. Radar and other methods of Intelligence provided the essential information which guided the actions of Fighter Command. But to be of any practical use, the information had to be communicated; so another piece of straight thinking had caused a nationwide Defence Telecommunications Control organisation to be set up. Dowding commanded through a network of permanent, duplicate and emergency telephone circuits backed by a teleprinter network. All this was provided and largely maintained by the Post Office. At times the communication web was stretched to its limit by enemy action, but it never broke down.

At the centre of the whole Dowding System was the underground, bomb-proof Operations Room at the Command Headquarters at Bentley Priory, Stanmore, with its neighbouring Filter Room sharing the same concrete bunker. In the Filter Room all the information from the Chain Home Radar stations, plus all that came in from other Intelligence sources, was pre-digested before appearing on the great chart in the Operations Room itself, where it was translated into battle orders. The most important of the 'other Intelligence sources' was the Observer Corps, a World War One survival, formed into a regular corps in 1925 and in 1939 consisting of over 1000 posts, each disposing of some fourteen-twenty observers equipped with binoculars, an instrument for relating sightings to a gridded map, the inevitable telephone, and means of 'brewing up' the essential 'cuppas' without which the whole British war effort would have collapsed. In 1940 there were 30,000 observers, all volunteers who strongly objected to receiving pay although they were entitled to it. They wore no uniforms beyond armbands and steel helmets when available; most of them fitted their Observer duties into fulltime jobs. In 1941 the Corps received the title Royal' and richly was it deserved.

The Stanmore Operations Room was the only room where aircraft tracks over the whole of Britain were displayed. Only here was the full picture of the Battle to be seen and followed as the industrious WAAFs placed and moved the symbols across the chart with their long 'croupier rakes'. And here, overseeing them all, sat Air Chief Marshal Dowding, alongside Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Pile who headed Anti-Aircraft Command, whose guns and searchlights were also part of Dowding's apparatus, and with them were the Commandants of the Observer Corps and Balloon Command and liaison officers from Bomber and Coastal Commands, from the Admiralty, the War Office and the Ministry of Home Security (controlling the men and women who had enrolled in Civil Defence, which was also part of the Battle), and there they watched Britain's fate unfold. The Operations Room at Stanmore in 1940 was the brain-cell of the defence of Britain, without which all else would have been blind, unco-ordinated and pretty much at the mercy of Hermann Goring's air armadas.

Dowding's system was an exercise of control and communication, and once plotted by the WAAFs and digested by the senior officers on the balcony the information which made a controlled battle possible was communicated outwards in 'cones'. The tip of each cone was a Group Operations Room modelled on the master at Bentley Priory, but covering only the Group area and its immediate fringe. The headquarters holding the Operations Room of No. 11 Group at the 'sharp end' was in Hillingdon House, Uxbridge, where Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park controlled the seven sectors directly facing the enemy in the Pas-de-Calais. Park and Dowding saw eye to eye; Park completely shared Dowding's sense of the system and of control. And that was just as well. From Group Headquarters the 'cones' broadened out to embrace the Sectors, which also had their Operations Rooms, and these were the final, executive links in the Dowding system. From them the combat orders went out to the base of the 'cones', the fighter stations. The Sector Controllers put the squadrons in the air, positioned them, and kept track of them by an ingenious Direction Finding device called 'Pip-Squeak', these Sector Controllers — mostly very young men, but experienced flyers — were key figures. Their voices on the 'inter-com' (High Frequency two-way ground/air communication), calm, measured and friendly, brought knowledge, support and reassurance to the young paladins in the sky; the Controllers regarded themselves as the servants rather than the masters of the flyers.

Such was the Dowding System, a delicately interlocking net of ground and air responsibilities, comprising a carefully tuned instrument of war of a kind never before seen in action. Like all air warfare, it ultimately reposed upon two things: first, a competent and tireless ground staff to place and keep the aircraft in the air — without that there is no flying, let alone air combat. And the second thing, of course, is the quality of the flyers, the boy pilots of Fighter Command. If they had been below the measure of their task, if they had faltered, no system could have won. But in this year of all years I don't have to tell you that no such thing happened — if it had, we would not be here now.

The Battle of Britain ended officially on 31 October. In fact, it was over long before that. We have to hold it in mind that Hitler had been thinking seriously about the attack on the Soviet Union almost from the moment that France fell; that was the work of lunacy; German divisions were already moving east before the end of June, and actual planning began in July. By September, the year was getting on, and Hermann Goring's promise was as far from fulfilment as ever. On 15 September, the Luftwaffe suffered an unmistakable defeat; there was no massacre of 185 German aircraft as the Air Ministry rather foolishly claimed — the actual figure was sixty-one. But sixty-one is a lot of aircraft to lose, and it was enough. Two days later came the first inkling that SEALION was being postponed or possibly abandoned. When the Luftwaffe switched from battling Fighter Command for air supremacy to night attacks on British cities it became clear that SEALION was a dead duck — and SEALION was what the Battle had all been about. Germany had suffered her first defeat of the war.

In battle, this was the achievement of what Churchill so aptly called 'the Few'. Before, during and after battle, the achievement of the Dowding System was to ensure that few though they might be, they would always be in the right place at the right time, and also, as I said in 'The Right of the Line', to ensure that 'however few the "Few", somehow there were always a few more. So Britain's first fight for survival was won. This was not totally apparent at the time — to people waiting night after night for the sirens that heralded the arrival of the bombers, and who rose with the 'All Clear' to count the cost of the new Blitz', there was not much to cheer about that winter. No enemy had set foot upon the island — that was the great thing; but we knew we were beset. We did not know, because we were carefully not told, just how hard beset we were. The second fight for survival was getting into its stride.

We must go back once more to that fatal day in June 1940 when France surrendered. It was on that day that the Battle of the Atlantic — the German campaign to reduce Britain herself to surrender by submarine action against her supply lines — really began. The reason for that is straightforward and strictly geographical. Germany is badly placed for sea warfare, including submarine warfare. It was a German fancy to call the North Sea 'the German Ocean'; it wasn't — the real German 'ocean', Germany's maritime 'doorstep', is the Baltic. Her Baltic and North Sea ports have only one reasonably direct access to the Atlantic; north about, through the waters between Scotland and Iceland. That is a long haul, seriously reducing patrol time on the great trade routes, and under close sea- and air-surveillance all the way. In June 1940 this disadvantage was wiped out at a stroke.

No-one had followed the advance of the German armies through France with greater attention than Admiral Karl Donitz, the Befehlshaber (what we call Flag Officer) of the German submarine arm, the U-boats. 'While the conquest of northern France was in progress during May and June,' he tells us in his Memoirs, U-boat Command had had a train standing by, which, laden with torpedoes and carrying all the personnel and material necessary for the maintenance of U-boats, was dispatched to the Biscay ports on the day after the signing of the armistice. The Biscay ports face out directly to the Atlantic itself. Effectively, from a U-boat point of view, there were five of them: reading from north to south, they were:

- Brest, at the tip of the long Brittany peninsula, a French naval base for centuries

- Lorient, on the south side of the peninsula

- St Nazaire, at the mouth of the Loire

- La Pallice, just outside la Rochelle

- Bordeaux on the Gironde.

Possession of these, says Donitz, meant that We should now have an exit from our 'back-yard' in the south-eastern comer of the North Sea and would be on the very shores of the Atlantic, the ocean in which the war at sea against Britain must be finally decided . . . All in all, possession of the Biscay coast was of the greatest possible significance in the U-boat campaign.

Donitz inspected the ports on the day after France surrendered, and decided to set up his own headquarters in Lorient. Work began immediately, and he and his staff moved in in November. The Battle was already well launched. From the British point of view, next to immediate successful invasion, this was the worst possible news. Lorient was the most important of the captured ports, with its substantial dockyards and dry docks. The first U-boat to use a Biscay port was U-30 (this was the one that sank the liner Athenia on the first day of the war); she came into Lorient to refuel and take in new torpedoes on 7 July; by 2 August the dockyard was able to undertake repairs. Shortly after, St Nazaire and Brest came into operation. What this meant was that U-boats now had a starting-point towards the vital British trade routes virtually as far west as the southwestern tip of England. And that meant that they would be able to operate as far out as 25 °W, whereas the convoy surface escorts operated only as far as 17°, and only flying boats could give air protection beyond 15°.

The organisation which dealt with anti-U-boat warfare was Western Approaches Command, commanded by Admiral Dunbar-Nasmith VC, himself a submariner of great distinction. Trade from all over the world came to Britain via the Atlantic, taking three routes as it approached its destination: through the Channel to the Thames and the Port of London — twenty-seven per cent of all Britain's imports came in that way, including over half the nation's meat supplies and the same proportion of butter and cheese, all making for London's cold storage facilities. Air attack forced ocean-going ships out of the Port of London, and aircraft and U-boats between them reduced imports through east- and south-coast ports by over two-thirds. That left only the Western Approaches: the South-West, via the south coast of Ireland and the Bristol Channel, and the North-West via Northern Ireland to Liverpool and Glasgow or round the north of Scotland to the east coast. The arrival of the U-boats in the Bay of Biscay compelled the Admiralty to abandon the South-West Approaches in early July. Effectively, this meant that all ocean-going trade would have to use the North-Western Approaches, and that was where the U-boats could now concentrate their attacks.

'Concentrate' conveys a concept; wars require more than concepts for fruitful operations. It is one of the many ironies of World War II, and a blessing for which we should never cease to give thanks, that at just the moment when Donitz enjoyed greater geographical advantages than he had ever dared to dream of — the whole European seaboard on the western side, from the North Cape right up at the tip of Norway down to the Spanish frontier, in German hands — the number of actually operational U-boats sank to its lowest totals of the war. Donitz had said, in 1939, that to blockade Britain decisively he would need 300 boats; in April 1940 he had thirty-one operational; in May the figure dropped almost to its lowest — twenty-three; in June it rose to twenty-six and mounted to twenty-nine in July. It was a far cry from the great packs that he would have liked to wage war with; they would have to wait until 1942 and 1943.

Donitz, like Dowding, had a system of war, and like Dowding's it was firmly based upon control, which in turn was based on communication. But unlike Dowding, in 1940 he did not have the means of putting his system into practice. He had to rely entirely on the skills of his peace-trained captains and crews, and they did not let him down. Once more, I'm afraid, I shall have to throw a lot of figures at you — figures which it is almost impossible to find mental images for: how does one make an image of half a million tons of shipping? It is hard enough to make a mental image of a convoy under attack — even a single ship. I said in 'Business in Great Waters':

In World War I the contemplation of great vessels suddenly smitten, perhaps in the dead of night, by shattering explosions caused by unseen foes, and rapidly disappearing under the waves with passengers and crews drowned, blown up, or exposed to lingering death in open boats, came as a deeply shocking novelty.

It was scarcely less so in 1939 and 1940; almost invariably the circumstances of submarine and anti-submarine warfare are horrifying, and what novelties 1939-45 added to the picture generally made it worse. Because the world depended far more on petrol than it had between 1914-18, tankers were a major feature of many convoys, and we had the stories of merchant seamen being roasted alive in the blazing oil of a torpedoed tanker, with the alternative, perhaps, of dying in a matter of seconds in the freezing waters of the Arctic. Those are the things that the figures mean — the endless statistics of the Battle of the Atlantic, of which Churchill said: 'How willingly would I have exchanged a full-scale attempt at invasion for this shapeless, measureless peril expressed in charts, curves and statistics!'

Well, here they are: May 1940 was the month when shipping losses suddenly jumped to their highest total so far: 101 ships, 288,461 gross registered tons. But May, as I have just said, was when the U-boats were almost at their numerical weakest, and they were only responsible for thirteen of the ships, 55,580 tons. By comparison, German aircraft sank forty-eight ships, 158,348 tons, their second highest monthly total of the war. And then the catastrophe really took off: the June total of sinkings by all causes was 585,496 tons, 140 ships, one of the really big totals of the war, and a cruel blow. U-boats accounted for fifty-eight of the ships, far more than any other single cause. In July they only sank thirty-eight ships out of a total of 105. The August total was ninety-two ships, just under 400,000 tons. September and October were even worse, 100 and 103 ships respectively, the two-month tonnage total being nearly a million, and the U-boat contribution being fifty-nine ships in September, sixty-three in October, a two-month tonnage total of 647,742. The October U-boat sinkings, for a reason that I shall shortly explain, were their best achievement so far: sixty-three ships, 352,407 tons. Their performance then dropped away sharply: thirty-two ships in November, thirty-seven in December. By the end of the year, the U-boats' twelve-month total was 471 ships and 2,186,158 tons. Well might Churchill say: 'What made it all worse was that in the whole year we had only managed to sink twenty-two U-boats (with one more lost in an accident) and the Admiralty had a very shrewd idea that such was the case.'

This period — the close of 1940 and the beginning of 1941 — was what the U-boat men came to call their first 'happy time' (their second and last was during the early months of 1942). It was also the time of the 'grey wolves' — that is a piece of German journalistic propaganda referring to the first batch of U-boat 'aces' who became as famous in Germany as the air 'aces' of World War I. In truth, Donitz's system had little use for brilliant individuals, but as I said earlier, the system was not yet in use itself. His sheer lack of U-boats continued well into 1941; in October 1940 he was down to twenty-six again, in November twenty-five, and in December the absolute rock-bottom: twenty-two. So during this bad phase it was 'grey wolves' or nothing. The three most famous names were Gunther Prien, whose U 47 had entered Scapa Flow in October 1939 and sunk the battleship Royal Oak; Joachim Schepke, a young man with film-star good looks and all the self-confidence and aggression in the world (his boat was U 100); and Otto Kretschmer, of U 99 who was known as 'the tonnage king' and of whom Donitz said that his 'exploits stood alone'.

There were others besides, and much emulation between them all, but these were the great names, the heroes of the whole U-boat arm. It was they who were largely responsible for the heavy sinkings of October. On four nights, 16, 17, 18 and 19 October, a small group of U-boats — not large enough to be called a 'pack' — attacked three convoys and sank no fewer than thirty- eight ships. It was quite simply, a catastrophe, and to those who knew what was happening the thought of a repeat performance was a nightmare. Captain Donald Macintyre, a tough, competent Escort commander, calls this battle of the three convoys 'the very nadir of British fortunes in the Battle of the Atlantic.' On what we may call the broad screen', we have to remind ourselves that, in the words of a German historian, 'for every two convoys that were attacked, twenty passed through the danger zone unmolested.' On the “narrow screen" of day-to-day and week-to-week events, it looked far less encouraging. One of our Official Historians, Professor Hinsley, has stated: 'the severe mauling of a convoy was the equivalent of a lost battle on land.' What, then, were the Admiralty and the Ministers concerned to think about an action in which convoys were suffering losses of twenty-four point five per cent (HX 79) and fifty-eight point eight per cent (SC 7). They had no idea how weak the U-boat force really was; they only knew that in the area known as the 'Bloody Foreland' off the north-west coast of Ireland U-boats seemed to be everywhere.

And they also knew how weak the antisubmarine forces certainly were. I said at the beginning of this talk that the three Battles — France, Britain, Atlantic — were intimately connected. Indeed they were. The Battle of France was what gave the Germans airfields just across the Channel, and U-boats bases on the shores of the Atlantic; the invasion which was decisively repelled in the Battle of Britain called for everything that the Royal Air Force and the Navy could throw in; the result was disastrous weakness in the Atlantic. To counter the invasion the Navy built up a force of some 800 light craft in the south-eastern area; convoy escorts were stripped 'almost to vanishing point' (in the words of the Official Historian Captain Roskill) — hence the fearful losses of merchant ships.

The RAF also concentrated its energies against the same threat, not only Fighter Command, but also Bomber Command and Coastal Command, bombing German invasion craft and keeping ceaseless watch on their preparations. There was very little left over for anti-submarine warfare, and what there was was generally obsolescent and feeble stuff. Not until August 1941 did Coastal Command overcome a U-boat by its own unaided efforts.

As the year drew to an end it took great courage and good cheer to view Britain's prospects with anything but horror. For all practical purposes of battle against Germany, we did not have an army. Nor did we yet have a war industry capable of equipping one. Our cities were under constant and damaging air attack. We had no independent allies able to support us. Since war began we had lost, from all causes, 1280 ships amounting to just under four and three-quarter million tons. Our ports — themselves under heavy bombing — were choked by some two million gross tons of shipping under or awaiting repair. The anti-submarine forces (Western Approaches Command and Coastal Command) needed more destroyers and corvettes, more aircraft with longer range and depth charges designed specially for air-dropping, more air-to-surface radar with higher performance, ship-borne radar which was only just coming into production, searchlights and flares and a great deal else besides. For making war we were in penury.

But whatever the sociologists may say (and nowadays you never know what they may say), as a nation we were not defeated or much downhearted. We had beaten the Luftwaffe, General O'Connor was on the march in Libya, we had the sense of an Empire behind us and a good friend across the Atlantic in the White House. And we had a leader who understood the art of imparting courage. So we wished each other a 'Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year' and got on with the job.

For more about John Terraine, see here.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles