The Greatest Trench Raid of the War: The 6th Londons near Hill 60, February 1917

Between 2002 and 2007 The London Branch of The Western Front Association published a series of 13 half-yearly magazines called 'Firestep'.

These were very professionally produced and contained excellently written articles from a large number of contributors.

These have been difficult to locate but, thanks to the loan of a set of these magazines, we can now make these fully accessible to all members via our website.

Below is an example of just one of the articles that were published.

The 2nd London Division was a pre - war division of the Territorial Force, composed mainly of units recruited in south-west and south-east London. On mobilisation in 1914 it retained its divisional integrity, unlike its sister 1st London Division, of which so much was transferred to other theatres and formations that it was broken up and not reformed until February 1916 in France. The C-in-C Home Forces, General Sir Ian Hamilton always gave glowing reports on the state of readiness of the London Territorials, and when 47th Division moved to France in March 1915, it was only the second complete territorial division to arrive there, a day or two behind the 46th (North Midlands) Division . It was a completely reliable formation that could be depended upon to do the job it was asked to do.

As part of 1st Army it saw action at Aubers Ridge and Festubert in May 1915, and did well at Loos in September. It had a torrid time at Vimy Ridge in May 1916 and, under Fourth Army, was heavily engaged on the Somme in September and October 1916 , famously as the division which finally took High Wood.

By the time they arrived in France that peculiar and unexpected deadlock known as trench warfare had become routine. It soon became obvious that it was important to control No Man's Land between the two front lines. It had to be denied to the enemy, to prevent him from springing any nasty surprises under cover of darkness. This could be done passively, by means of listening posts, or actively, by means of patrolling. The General Staffs of 1st and 2nd Army were issuing guidelines for keeping trench warfare active from December 1914 onwards. It was as much to prevent British soldiers from becoming too passive, from slipping into cosy "live and let live" arrangements with the enemy, as anything else.

Before long, those units with strong esprit de corps took this work in No Man's Land a stage further. Having patrolled boldly right up to the enemy's wire, and occasionally finding his front trench empty and entering his lines, it was a logical step actually to attack the enemy under cover of darkness - the birth of the trench raid. The motive was, early in the war, as much to show " Fritz " who was boss as anything else. It was an act of pure aggression by élite units. The gathering of prisoners for purposes of identification was a bonus; the principle aim was to kill the enemy, destroy their defences and make life unpleasant for them.

It was a peculiarly British invention at first; it is called Britain's unique contribution to the science of trench warfare. The French were firm believers in "live and let live"; the Germans seem to have been dragged into a policy of trench raiding as reprisals for British impudence. Towards the end of 1915, after nearly a year of occasional buccaneering raids, they changed in nature. There is a dispute over the first of the new style raids. Most people give the credit to the Canadians; it is also claimed by the Worcesters. But there was a quantum leap in the way the raid was planned and it became a "battle in miniature". There was a very elaborate artillery support programme; long periods of preparation and special training; pages and pages of orders / instructions / exigency plans as if for a major, set - piece battle.

The 47th Division was well used to trench raiding and had a couple of good "stunts" under its belt, mostly carried out by 140th Brigade. When orders arrived for an unusually large raid to be carried out in late February 1917 on an enemy salient near Hill 60, one of that brigade's battalions was a natural choice. The 6th Battalion, The London Regiment (The City of London Rifles), who knew themselves as the "Cast-Iron Sixth", was the one selected. In February 1917 they were in hutted camps behind the Ypres Salient and on the first of the month they began a normal programme of training; PT, bayonet exercises, section and platoon drill, with a two hour route march by companies in the afternoon. That evening the brigade commander (Brigadier-General Hampden) informed them that they would be required to carry out a battalion - sized raid in the Bluff Sector on or about February 20th. Normal drills continued for a day or two. It is important to note that on February 2nd the battalion war diary recorded that "In view of the new organisation Bombers and Lewis - gunners ceased to exist as separate units and were incorporated in their respective platoons". This is an early confirmation of a major reorganisation of the British infantry as the BEF integrated the lessons of the Somme fighting into its principal combat arm. The important new training pamphlets, SS143 ("Instructions for the Training of the Platoon in the Attack" and SS144 ("The Normal Formation for the Attack"), explained the new formation and battle drills.

By 4th February they were at Dickebusch Camp where a training ground had been laid out with tapes with the help of the brigade major. Next day the commanding officer (W.F. Mildren) and the brigadier made a reconnaissance of the trenches; a brigade conference began the planning process that afternoon (the divisional commander, Major General Sir G. F. Gorringe attended). From the 8th February the men begin rehearsing the attack in the afternoon, while normal training continued every morning, including lectures on the new training pamphlets SS143 and 144. On February 10th another reconnaissance was made and a conference fixed 5 pm on the 20th as the date and time for the raid, and decided roles for the artillery, Stokes trench mortars, engineers and tunnellers. Daily lectures by platoon commanders discussed the coming attack, platoon co ordination, the artillery programme, and made critiques of the training to date. The lecture on 11th February was entitled "The coming attack; Objectives of each Platoon and the Importance of Co-ordination". The raid was practiced every day up to 18th February, witnessed by generals all the way up to X Corps Commander Lieutenant General Sir T. L. N. Morland. Lectures were given on Esprit de Corps; box respirator drill was practised almost daily; the medical officer checked all field dressings and made sure their use was understood.

The battalion reports of the preparations for the raid make impressive reading; they show that the officers made plans for every eventuality in the chaos of battle. Principally, it was made certain that every man knew what was expected of him.

"Special attention was paid to the following points:

1. That every man possessed a working knowledge of the plan and object of the whole scheme.

2. A thorough understanding of their individual work, the time schedule and the signals.

3. The importance of securing prisoners, papers and documents, and anything which might be useful in furnishing information.

4. Sequence of command.

5. Simple German phrases"

It is an interesting piece of social history of the time to note the record that some 25% of the men wore wrist watches. These were regulated and synchronised every day and at every practice, and twice on the day of the attack.

The careful planning detailed the kit to be worn and carried: haversack, water bottle, entrenching tool and respirator. Raiders normally went over with less kit but this was more miniature battle than raid. Bombers and rifle grenadiers and their carriers all took sixteen bombs in canvas buckets; all other men carried two grenades in their pockets. The numbers of wire cutters, lengths of rope, electric torches, traversing mats, ladders and phosphorous bombs to be carried per company were all specified. A senior artillery officer was attached to the CO of 6th Londons for close liaison, and a forward observation officer and two telephonists went over and set up a communications point in the German front line. Two further telephone lines were to be run out from the British to the German front line.

A very elaborate series of code words was issued to be used in messages sent during the raid. Units of the RAMC were to take over the running of the battalion's dressing station to leave the medical officer and all the stretcher bearers free to go forward with the raiders. One man with knowledge of the German language went forward with each company commander. The battalion was urged to collect its prisoners and forward them to brigade as quickly as possible. Men were warned against enemy "treachery". The use of bogus white flags and "false surrenders" was to be guarded against. But at the same time, the men were enjoined not to throw bombs into manned enemy dug - outs unless the occupants refused to come out. No raider was to go forward with any means of identification, either individual or regimental, about his person.

The battalion left its camp at 5 pm 19th February and two hours later relieved 8th Londons in the front line trenches. The men were exempt from all other duties and got something of a rest. The special materials for the raid (ladders, ropes, mats, bombs, etc) were brought up during the night and distributed. That night the Lewis gun teams swept No Man's Land with fire to prevent German working parties from repairing their damaged barbed wire.

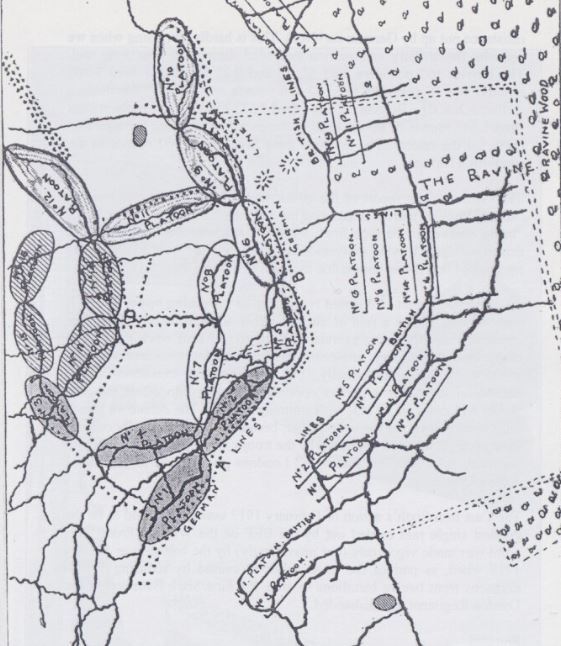

The objectives were several: to inflict casualties, capture and destroy matériel, destroy defences, gather information on enemy defence systems, destroy mine shafts and gas cylinders. The 5 pm zero hour was in daylight for maximum control; the men were to be in the enemy lines for one hour and would be withdrawing in dusk. The size of the raiding party was exceptional, comprising all four companies (with six Lewis gun teams) of the battalion, in total eighteen officers and 626 men. They were to be accompanied by an officer and twenty sappers of 520th Field Company RE and an officer and four men of 2nd Australian Tunnelling Company RE, who were to carry out demolitions.

They went over in four waves of six, three, five and two platoons respectively, Lewis guns and sappers going in with second wave . Artillery preparation was by 47th Division's artillery, plus 28 guns of 23rd Division, 20 of 41st Division, two groups of Belgian artillery, X Corps heavies and twelve field guns from corps reserve. All the machine guns of 47th Division and most of those of 23rd Division were assigned to fire in support. Stokes mortars supplemented the barrage on specific sections of the line. A dummy raid was laid on at Hill 60, involving the blowing of two small mines and artillery bombardment. A squadron of the RFC flew several missions over Hill 60 to heighten German anxiety over that part of the front and away from the raid. 41st Division fired a "Chinese" (diversionary) barrage south of the canal. Smoke barrages were put down on either side of the raid to obscure enemy vision from Hill 60 and the Caterpillar. All the other arrangements (for handling prisoners of war, for medical services and signals) were as complete and detailed as for a major battle.

The artillery and trench mortars had been firing wire - cutting missions for several days but over a widely dispersed area; a German officer prisoner said they were completely unaware of the point to be attacked. All the attackers were massed in the front line trench by 4.45 pm 20th February. The war diary reports: "The men were cheery and confident, and showed no signs of nervousness".

At 4.55 pm the nines were blown at Hill 60 and the diversion programme got under way. The main artillery opened up at 5 pm. The first infantry went over at 5.03 , followed at fifty yard intervals by the other three waves. They were lead over by Captain (Acting Major) Neely, in incorrigibly British style, sounding a hunting - horn! George Neely was a pre-war officer and originally commanded the battalion's signals section. On mobilisation he became the transport officer and was an excellent administrator. That he was known as "Kate" to his drivers and grooms in the horse lines might normally set alarm bells ringing! He was tall and always immaculate; in speech and bearing he was "charmingly foppish", having a "languid and disdainful exterior ". He sounds like a popular caricature of a British officer but we must not be thus misled in our judgement of him. Promoted to the command of D Company in April 1916, he proved himself to be one of the most deadly efficient combat commanders, and an inspiration to his men. He routinely commanded the battalion when Colonel Mildren took over the brigade in the brigadier's absence.

The wire was swept away; the enemy were taken by surprise; his numerous machine - guns were still in their concrete shelters. The attackers swept over all three lines of the enemy front system, fire, support and reserve trenches. On a front of 550 yards, they penetrated for 300 yards. All the attackers remarked on the excellence of the enemy trenches, especially the dugouts, which the sappers and tunnellers began to demolish as soon as they arrived. The Lewis gun teams and rifle grenadiers worked on the flanks and did tremendous execution on the enemy who tried to flee the scene. (We see here for perhaps the first time the new SS143 tactics in practice.) One eyewitness reported that of a party of forty enemy soldiers in flight, some thirty were seen to fall under the fire of the Lewis guns. German retaliation fire was uncoordinated, especially concentrated around Hill 60, with a bombardment falling on the empty British front line. The Germans surrendered very freely, but one officer was discovered at a switchboard speaking into a telephone and who refused to stop when told to do so "was killed with a bomb". Weapons were gathered up and destroyed; all papers, plus examples of equipment and food, were sent back. (One large box of explosive aerial darts was recorded as "sent back" but later "could not be traced". Perhaps some weary Tommy assigned to the task took the first opportunity of dumping it in a suitably flooded shell hole!)

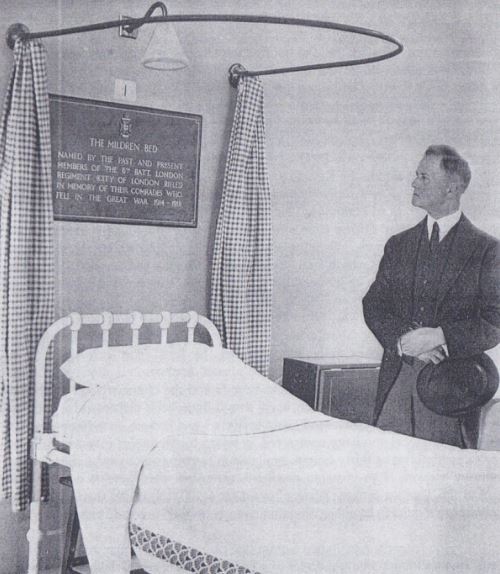

The retirement began promptly at 6 pm. All returnees were back by 6.25; the battalion dispersed quickly to normal trench - holding mode. It was relieved next day by 17th Londons and returned to the training camps. The losses totalled 76; an acceptable figure given the size and extent of the raid. Four officers were wounded, eleven other ranks were killed, three died of wounds and two were missing; 55 men were wounded, mostly with light wounds and soon returned to duty; one case of shell shock was recorded . After a good rest, and successive visits by Major General Gorringe, Lieutenant- General Morland and 'Daddy' Plumer himself, it was back to training ready for normal trench duty before the end of the month. Plumer was greatly loved by the men of Second Army but was no great orator. He told the battalion after a church parade," Fine performance; very good, very good. But - er - we haven't won the War yet". Colonel Mildren received the DSO for this action and the battalion was awarded a total of four Military Crosses, two Distinguished Conduct medals and no less than sixteen Military Medals.

The destruction of enemy property was carefully listed; 44 dugouts, an artillery signals switchboard, machine gun and trench mortar emplacements, sniper posts, ammunition dumps etc. The trench system in the rear was generally wrecked. The enemy dead and wounded could not be counted but were considerable .But besides bringing away two heavy and three light machine guns, the Londoners captured the astonishing total of one officer and 117 other ranks (two of whom died in our trenches from wounds received).

The after-action reports attribute the success ( particularly the low casualties ) to the diversions , the counter-battery work of the artillery, the speed of the infantry in following the artillery barrage, the prompt dispersal after returning to the British trenches and the very light garrison in our own front line. The reports by each company all stress the devastation caused by the British artillery and the relatively weak resistance put up by German survivors. This is hardly surprising when we consider the artillery ammunition expended during the hour long raid. The heavies (60 pounders, and 6", 8" and 9.2" howitzers) fired 1,900 rounds. The 18 pounders fired 17,756 rounds and the 4.5" howitzers a further 3,268. The Belgian 75mms fired 1,583 rounds. 2" trench mortars fired 1,563 rounds of smoke shell in the excellent covering barrages that protected the raiders. The machine guns fired off 43,000 rounds in the supporting barrages.

The German news report of the attack was a fantastic one , referring to "strong English patrols attempting to advance after exploding mines", "being checked by barrage fire" , some few reaching the lines but being driven out again leaving unwounded prisoners - who "were so absolutely intoxicated that it was impossible to interrogate them"!

An important aspect of this raid is its value as a training opportunity. It was, in fact, hardly a raid at all, but rather a battle in miniature. The preparation and planning exercised all aspects of staff work right up to corps level, as artillery, engineers, medical and logistics services were coordinated. Most importantly, the planning and execution at the regimental level was a perfect opportunity to put into effect the new tactics laid down in SS143, with stunning success. The debate on trench raids usually revolves around whether, because they were usually ordered from on high, they were detested by the troops, or whether they cost more than they achieved. This raid by 6th Londons gives the lie to both those accusations.

The Cast Iron Sixth's action of February 1917 was widely held to be the greatest single raid carried out by the BEF on the Western Front. This point was made vigorously (but unavailingly) by the battalion in January 1918 when, as part of the huge upheaval caused by reducing British divisions from twelve battalions to nine, the First / Sixth Battalion of the London Regiment was disbanded.

Sources

Maude , A.H. The History of the 47th ( London ) Division 1914-1919 London 1922

Godfrey, Capt . E. G. , MC The "Cast-Iron Sixth" : A History of the Sixth Battalion London Regiment Stapleton London 1938

WO95/2702 47th Division General Staff

WO95/2728 140th Brigade Headquarters

WO95/2729 1/6th Battalion London Regiment (City of London Rifles)

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

Identify key words or phrases within back issues of our magazines, including Stand To!, Bulletin, Gun Fire, Fire Step and lots of others.

The WFA's YouTube channel features hundreds of videos of lectures given by experts on particular aspects of WW1.

Read post-WW1 era magazines, such as 'Twenty Years After', 'WW1 A Pictured History' and 'I Was There!' plus others.

Other Articles