Lt. Col. John Brough: The Commander Of The First 'Tankies'

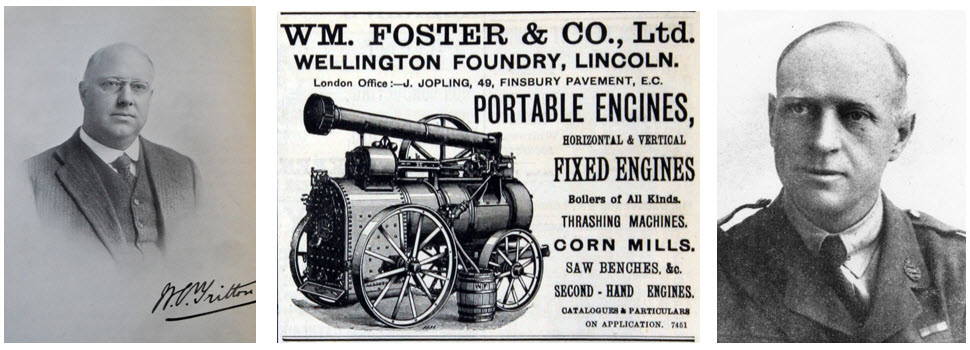

Like all eventually successful projects, that of the genesis of the 'Landship/Tank' project during the Great War had many putative 'fathers'. They ranged from Leonardo da Vinci and H.G. Wells to E. D. Swinton and W. S. C. Churchill. Indeed, after the end of the Great War, there were so many claimants that the British Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors (1919) held special sessions to decide who could genuinely claim to be the definitive inventor of the 'tank' and thus be eligible for compensation by a grateful nation. A lump sum of £100,000 sterling (£10 million today) was postulated for the individual successful claimant. The conclusion of the Committee was that no specific person could be identified. It decided that many people had paid a greater or lesser role in its genesis from an idea to a potent new weapon of war, if not exactly a campaign-winning weapon: that was to follow in later wars. In the end, the Commission paid lesser sums to several of those involved. The largest amount being £15,000 shared between the prime contractor of the prototype, William Ashbee Tritton, William Foster & Co,. Lincoln, UK. and his designer, Walter Gordon Wilson, Royal Navy.

On the other hand, the records of the Great War show that there is no doubt who was the British Army officer that had readied and commanded the first British tanks to go into battle on the Western Front. (And, coincidentally, these were the first purpose-made armoured, tracked, and internal combustion-engined chariots of war to go to into action anywhere). His name was John Brough - pronounced Bruff – (hereafter JB) and he was a Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) of the Royal Marine Artillery (later of the Heavy Machine Gun Corps); he was also familiarly known as the 'Commander of the Tankies'.

As we shall see, JB played the leading role in forging his disparate volunteer tankies into a working unit overcoming the initial teething problems of a new weapon of war and its introduction onto the battlefield of the Western Front. He also prepared the first manual on tank tactics on the battlefield (see 'Acknowledgements').

Background

JB was a true sailor/soldier of the British Empire. He was born in 1872, in what is now the Pakistani part of the Punjab, into an established military family of the British Raj. He received training in the British naval and military establishments at Greenwich and Camberley respectively. Pre-1914 he served with Royal Navy and the British West African Frontier Force (WAFF) as well as a gunnery officer (Royal Marines) on several Royal Navy warships. He was also a tutor at Sandhurst Military College, UK.

When the Great War began in 1914, JB was in his early forties and a substantive major. He became a wartime temporary Lieutenant Colonel and was sent out again to West Africa to participate in the campaign to expel the Germans from their colony of Kamerun (German Cameroon) – a rugged campaign that lasted until 1916. He was eventually repatriated to the UK having acquired what was probably the malignant strain of tropical malaria (Plasmodium falciparum), and was subsequently transferred into the Royal Artillery. From there he became involved in the Heavy Section of the Motor Branch of the newly formed Machine Gun Corps in May 1916. (In 1914/15 the then Motor Machine Gun Service was administered by the Royal Artillery). This Heavy Section was formed to bring into operation the new and secret armoured tracked vehicles – tanks - that were the outcome of the Admiralty sponsored Landship Committee project. The chosen production model of the tank was called 'Mother' and 100 were designated for the Western Front.

Getting the tanks onto the Somme battlefield

At the end of 1915, it was decided that the British Sector troops in the Arras/Somme Sector would play only a minor role in a planned joint Anglo-French offensive on the German front-line following the now standard frontal attack scenario. The French were to play the major role in what was seen by them as a battle of attrition to weaken the German Army. But the success of the German offensive at Verdun forced the French to ask that the British take the lead role in the 1916 Somme Offensive as soon as possible. So, in March 1916, at the request of the French, the British Fourth Army also took over a large sector of the French lines in the Arras/Somme area.

Accordingly, at forefront in the minds of the commanders of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was the ever increasing pressure to meet this commitment to relieve German pressure on the French Army at Verdun, but at the time same achieving the long desired ambition of the British to obtain a significant 'breakthrough' against the Germans.

All the while, at Verdun itself, a huge maelstrom of a battle was underway. The Germans were determined to force the French, in turn, into a battle of attrition as the French Army strove, at all costs, to repel the invaders and retain their hold on the 'sacred' territory of Alsace/Lorraine.

Kitchener's New Army volunteers formed the bulk of the British infantry battalions in the new offensive. British plans increasingly included the deployment of the new Mark I tanks in this attack with the agreed production figure rising to 150 tanks; equivalent to six companies with 25 tanks each.

JB spent the first few months in his new post in the remoter parts of the English countryside demonstrating the operational characteristics and potentialities of the still secret new armoured vehicles – the tanks – to various military and political figures including King George V.

In July 1916, JB was officially appointed as the second in command of the Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps under Lt. Col. E. D. Swinton, with specific responsibility of getting the tanks to France and making them operational. Effectively he would be the field commander whilst Swinton 'looked after the shop' at home.

Inevitably, the question was again raised whether the tanks should be sent piecemeal to France or held back to provide a tactically significantly large number of them for the first foray into battle. This single large, and hopefully still secret, consignment of the tanks would then be deployed in a large co-ordinated attack. Thus, the element of surprise would be retained to achieve the maximum shock effect on the enemy front-line troops.

However, the commander of the BEF, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, already knew there would not be any tanks available for the first days of the Somme offensive but decided to follow the military maxim of 'use as them as soon as they are available'. So, instead of waiting until January 1917, when a total of 500 tanks would be at his disposal, Haig decided to proceed with the 150 promised for September 1916, since that best fitted in with his then current operational plans for the Somme campaign. Little thought was given at BEF HQ as to whether the men and the tanks could realistically be ready for action by that earlier date.

JB found himself in unenviable position. He lacked the requisite authority to make the necessary decisions about the deployment of the tanks, whilst those who had the authority at BEF HQ constantly bickered among themselves about the whys and wherefores of tactics and deployment. Even worse, there were no spare parts currently available for the tanks, whilst the mechanical reliability of the tanks was already known to be inherently poor.

Accordingly, JB had busied himself to the best of his ability with arranging transport for men and machines, including a railhead, accommodation and training grounds for whatever number of tanks and men would arrive at the receiving depot in France.

JB's protests to his supervisor, Swinton, about the continued combat unreadiness of both the tanks and their crews went unanswered due to the perceived critical tactical need to get the tanks into action as soon as possible. JB faced his 'impossible' task with resolution.

Meanwhile, under JB's supervision, security in the tankies base area near Abbeville in northwest France was enhanced, as was the civilian and military postal systems, to avoid any lapse in secrecy. To further maintain security the tanks were shipped across France at night, suitably camouflaged on railway wagons and escorted personally by the tankies themselves. There were many problems with bridges and tunnels that had to be resolved or the tanks risked being marooned in transit and effectively kept out of service.

In August 1916, JB set up a Tank HQ and the first tranche of five tanks were demonstrated to Field Marshal Douglas Haig and his staff. But for JB's taste there were far too many other jamborees for the entertainment of the great and not so great. Accordingly, he complained vehemently about the waste of valuable training time that these 'circuses' entailed. Moreover, he clearly understood that once the tanks were formally ordered into action, command over their deployment shifted entirely to the operational commanders; the shepherd would hand over his 49 available sheep to the slaughterers.

At this point, even before the tank offensive began, JB was made persona non grata at BEF HQ for being 'difficult' and disappeared from the scene in early September 1916: he had been relocated to the UK and faced an uncertain future.

Eventually, after participating in various UK 'post mortem' meetings on the Somme tank fiasco, JB was formally installed at the London HQ of the Heavy Branch (Tanks) as a Staff Officer.

Third Battle of Ypres

On the 25th July 1917, JB was transferred with the 61st Division (2nd South Midlands) and joined Fifth Army in Flanders as a staff officer involved with preparations for, and participation in, the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). His exact role is unknown but presumably it had to do with deployment and field training for the 100 tanks assigned to the offensive. On the 27th July 1917, he presented his recommendations for the deployment of tanks in the Ypres offensive of the 31st July 1917.

The demise of J.B.

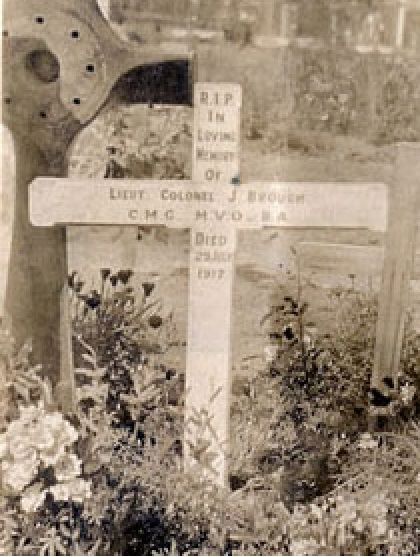

How JB killed himself on the 29th July 1917 is not in doubt – he shot himself in his right temple with his own British Army issue pistol whilst walking in the open countryside near his base. But exactly why he killed himself is another matter entirely. That it was not in any way an unfortunate accident is made clear by the fact his first attempt at suicide failed because of a faulty round, and he had to activate the trigger a second time to do the deed.

The most charitable and likely explanation for his suicide is that he was one of the many cases that we would today describe as 'Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)'. Or what was already in 1917 being widely called 'Shell Shock' by the soldiers on the Western Front and their families on the Home Front. However, even at this late stage of the war military doctors were still diagnosing officers with shell shock by euphemisms such as 'Effort Syndrome' (ES) and 'Disordered Action of Heart' (DAH). Definitely, JB was in a depressed state after the tank fiasco at the First Battle of the Somme for which he was clearly blamed in some way. Also, perhaps he feared that the same thing would happen with the British Third Ypres offensive (Passchendaele) that began just two days after his death.

It seems JB was just another tragic casualty of the stresses and strains of total war that few men in his place could face with equanimity.

Conclusion

Readers will have observed that these notes on JB are rather sketchy for which there is a simple explanation. Unless there were really extenuating circumstances, Great War soldiers who deliberately chose to commit suicide on active service were not usually respected or openly mourned by the military establishment or their comrades-in-arms. And this was particularly the case with suicide commissioned officers whom were seen to be cowardly in abandoning their men in extremis. Such soldiers were usually quickly forgotten and all mention of them minimised in the military records.

In the case of JB, it was his brother, another senior British Army officer - who also served on the Western Front - that attempted valiantly with some success to rehabilitate his brother's memory. Principally, it would seem, to find some solace for their devastated father, another career army officer. Eventually, a compromise verdict of a pardon was granted.

Coincidentally, JB's brother's efforts left a convenient paper trail for later historians to follow to shed some light on his demise and what followed.

Acknowledgements

The story of the genesis and deployment of the British tank in the Great War is a topic that has been studied and written about perhaps as much as almost any other. Many of the primary source documents are held in national archives in the UK and overseas, whilst the secondary sources, such as books and journals, are numerous but often out of print and, when they are available, expensive to buy.

John Brough's 'Notes on Tactics for Tanks', dated 11 June 1916, is available below.

Fortunately, books on this subject are continually being published and one that is particularly accessible to the amateur historian, is Christie Campbell's 'Band of Brigands: The first men in tanks'(2007 Harper Press). This author found it to be an excellent and informative read and a very useful source of little known references and facts for the amateur historian.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

The WFA regularly makes available webinars which can be viewed 'live' from home. These feature expert speakers talking about a particular aspect of the Great War.

Featured on The WFA's YouTube channel are modern day re-interpretations of the inter-war magazine 'I Was There!' which recount the memories of soldiers who 'were there'.

Explore over 8 million digitized pension records, Medal Index Cards and Ministry of Pension Documents, preserved by the WFA.