Neutralising The Scourge Of War Related Infections On The Western Front In The Great War

It was only a relatively small cadre of mathematicians, linguists and cryptographers of the interception centre at Blechley Park in southern England that brought about the war winning exploit of the Ultra code breaking operations in the Second World War. An even smaller cadre of immunologists based in a London hospital successfully struggled during the Great War to control some of the more pernicious diseases that had plagued the soldiers of earlier European Wars.

Potentially, one most important diseases that could be anticipated to occur among troops in the static conditions of trench warfare on the Western Front was typhoid. The second and third were, respectively, a group of manured soil related diseases associated with gangrene that infected the damaged tissues of the soldiers caused by the trauma of war from missiles and explosions, and the disease tetanus commonly known as 'lockjaw'.

Background

Typhoid:

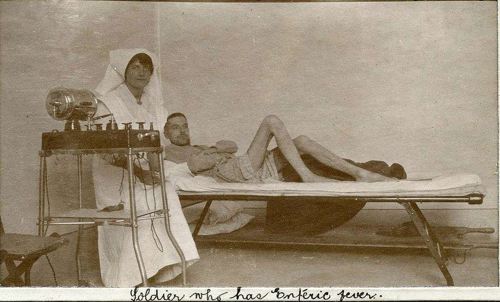

Salmonella typhi is a severe bacterial disease characterised by high fever, prostration, abdominal pain and a typical rash. It was also widely known in the past as enteric fever or The Enteric. Queen Victoria's husband Albert died of it, and perhaps the most common cause of non-violent death found engraved on the graves of British colonialists and soldiers of the British Empire is 'Died of the Enteric.'

The bacterium is shed in the faeces and urine, and infected 'carriers' of the disease, who often show no symptoms themselves, are largely the source of its transmission to healthy persons ? the so-called infamous 'Typhoid Mary carriers' of the disease. In particular, poor sanitary conditions can result in the contamination of drinking water and food. Also, flies frequently transmit the disease from infectious faeces directly to food.

The illness is prolonged and the fatality rate before the onset of modern antibiotics in the late 1940's was about 12%; the cause of death being primarily intestinal haemorrhage or perforation of the bowel. However, even patients who recovered often required a protracted convalescence, and a spontaneous relapse occurred in about 10% of the cases.

Historically, the disease was extremely common in military campaigns, with extremely high numbers of troops being affected: it was particularly associated with sieges and other static forms of warfare.

The diagnosis of the disease was often confused with tuberculosis and/or malaria. Also for many years' typhoid and malaria were erroneously thought by some military physicians to be part of the same disease pattern ? a sort of composite disease.

Gangrene:

Species of a bacterium of the genus Clostridium can infect serious wounds and invade deeply the tissues including the muscles. Once established, the bacteria produce toxins that destroy the tissues and generate a gas that further facilitates the spread of the infection into the undamaged tissues and muscles. Before the introduction of antibiotics the only treatment was the radical excision of the infected area by surgery (debridement) or amputation of the affected limb.

The penetrating wounds caused by missiles such as bullets or shell fragments produce large, deep, wounds that provide the ideal conditions for the bacteria of the Clostridium spp. since infected adventitious material such as clothing and dirt could be carried deep into the wound by the bullet or shell fragment. The possibility of infection was greatly enhanced on the Western Front due to the richly manured state of the soil (i.e. containing huge numbers of Clostridium bacteria) in most of the battle zone, and the delay with which casualties received effective medical treatment. Evidently, in the areas of desert warfare, across the Globe where the ground was relatively uncontaminated by manure and the concomitant Clostridium spp., the disease was comparatively rare.

Tetanus:

Clostridium tetani is, as the name indicates, a disease caused by bacteria of the same genus as gangrene. Its bacterial spores are similarly found in land that is heavily manured by domestic animals. Likewise, it is readily transmitted by penetration wounds caused by missiles such as bullets and shell fragments. But even minor wounds due to cuts, grazes and burns may also get infected. Obviously, in the environment of the debris and danger strewn trenches of the Western Front such minor wounds were a frequent and ever present danger.

The disease presents itself initially by an increasing stiffness of the jaw muscles; hence the common name of 'Lock-jaw'. Later, as the disease progresses up the nerves and in the bloodstream of the patient, the fixation of the muscles becomes more general, spasms become more frequent and a fatal spasm or coma may ensue. Untreated tetanus has a 50% fatality rate.

Researchers and inoculators

The audacious success of the British physician Edward Jenner in 1796 in the development of a simple but effective vaccine against small-pox led others to consider what other diseases could be ameliorated in this way. But it was the disastrous casualty rates from typhoid in the Boer War from1899 to1902 that provided the real impetus for research into this particular disease. Out of a strength of 210,000 British soldiers who served in the Southern African campaign, 13,000 died from typhoid (6.2%) and 64,000 (30.5%) were medically evacuated due to the disease.

From 1908 onwards a group of doctors at St. Mary's Hospital, Paddington, London took a really serious look at the deployment of a vaccine for typhoid that they had been working on for some time.

It had been well understood by the turn of the 20th Century that non-fatal exposure to communicable diseases often conferred future immunity, either partial or complete. Antibodies were produced that remained in the blood and would attack and neutralise any future attack of the disease. It was also understood that if weakened, or dead, organisms of the disease were inoculated into the patient they could also often produce the same immunity without seriously compromising the patient's health. Indeed, Jenner had used the closely related organisms of cowpox for his human smallpox vaccine. He had observed that milkmaids infected with cowpox usually didn't get smallpox and were thus free of the disfiguring scars found on many their contemporaries who had suffered, but recovered, from the often fatal disease.

Whilst the St Mary's Hospital team was made up of several members, the leading lights of the research effort were Drs Almroth Edward Wright (later Consultant Physician to the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front) and Alexander Fleming (later of penicillin fame).

The campaign against typhoid

Wright and his group campaigned vigorously to have their vaccine for typhoid made compulsory for all soldiers serving in the Boer War, but this approach was rejected by the War Office and only volunteers were given it. It is true that adverse reactions were more severe and debilitating in those early days, and this led influential and authoritative military medical figures such as Sir David Bruce to oppose its general deployment. Eventually, even the voluntary inoculations were stopped. Wright and his team were deeply disappointed but carried on their research. After many battles with the War Office the vaccine was reintroduced on a voluntary basis.

Accordingly, when the Great War commenced Wright and his team were ready with an improved vaccine. Wright spoke personally to Lord Kitchener, the then Secretary of State for War, making a strong case for its deployment. Kitchener, well aware of the problems with typhoid in past British Army campaigns around the Globe, became a strong supporter of the universal deployment of the vaccine. Henceforth, the Army, seeing the way the wind was blowing, did encourage Regimental Medical Officers to do all they could to spread its voluntary use among the men in their charge.

Meanwhile, Kitchener, in his typically pragmatic fashion, issued an order that soldiers who were not inoculated against typhoid would not be allowed to leave British shores. In the general determination at the time not to miss the 'Show', many soldiers were only too anxious to volunteer and the number of inoculations rose enormously.

With the majority of soldiers so protected the incidence of cases of typhoid remained low from the outset of the fighting on the Western Front.

Casualty rates from typhoid fever

The actual number of deaths from typhoid in the Great War was 1,200. Whereas it was postulated that without the vaccine these figures would be a hundred times greater. Certainly, on the Western Front the number of unvaccinated hospital admissions for typhoid was 15 times greater than it was for the inoculated and the death rate was 70 times higher.

Conclusions

From these relatively modest, and hesitant, beginnings the British Army firmly accepted the principle of preventive inoculations and all soldiers joining the British Army were immediately covered by a growing and compulsory armamentarium of vaccinations.

The Great War on the Western Front was the first major war in British Army history where the numbers of wounded and dead from battle wounds was not greatly inferior to that from non-battle wounds, i.e. mainly infectious diseases: the ratio was only 1:1.3. Of course, in tropical war zones such as the East Africa (1916-1918) disease rates remained high and the comparative ratio was 1:20.3. Effectively, in the long run, Caucasian soldiers were eventually excluded from the war in the Bush: it was mainly fought by African colonial soldiers supported by huge numbers of native porters and carriers.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

This magazine provides updates on WW1 related news, WFA activities and events.

Access online tours of significant WWI sites, providing immense learning experience.

Listen to over 300 episodes of the "Mentioned in Dispatches" podcast.

Other Articles