The British 'Clay-Kickers' and 'Moles' of the Western Front

As the war on the Western Front became static and the opposing armies found themselves trench-bound, the open ground between the trenches became so hazardous that it could only really be ventured into under the cover of darkness. And even then many dangers lurked. Eventually, the troops of both sides led an increasing troglodyte existence of which digging and tunnelling became an essential part and a survival skill.

Enter Major Norton Griffiths

For some time, since late 1914, British Army commanders, including Sir General Henry Rawlinson, IV Corps, British Expeditionary Force, had expressed serious worries about the evidence of tunnelling and underground mining by the Germans on the Western Front. However, in February 1915 it was the Conservative Member of the British Parliament for Wednesbury, and former mining engineer, Major (Sir) John Norton Griffiths, who broke the deadlock. Seriously alarmed by the firing by the Germans of 10 small underground mines on the 20th December 1914, under the Indian Corps in the Festubert Sector of the Western Front, he approached Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, with his concerns. Lord Kitchener and Major Norton then quickly succeeding in convincing the British Government that the British Army should reciprocate by systematically tunnelling and mining* the German front lines.[1]

Major Griffiths, under the auspices of the Army Engineer in Chief, Brigadier-General Fowke, was quickly authorised as a liaison officer to begin the enlistment, or transfer, within the Armed Forces, of former miners and engineering excavators into British Army Specialist Tunnelling Companies (Royal Engineers) for this express purpose. The importance that was given to this work from the outset, can be appreciated when the daily pay of the experienced miners and excavators in these tunnelling companies was set, outside the army's guidelines, at six shillings. This was extremely generous, when compared to the infantryman's one shilling and the ordinary sapper's two shillings and sixpence.

Although all the combatant nations had civil industries that involved tunnelling and mining, the British were particularly fortunate in having large cadres of men who were highly expert in this field. From the tin-miners of Cornwall, to the nearly one million coal miners of Wales, England and Scotland, these were men who could be called upon to bring their knowledge and expertise to the trenches of the Western Front.

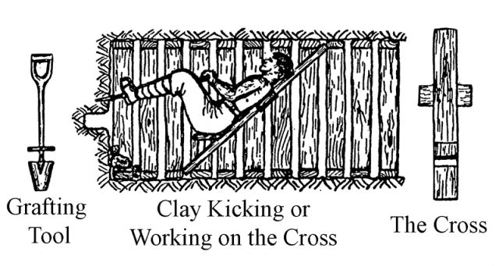

In addition to the versatile former coal and tin miners (nicknamed by other soldiers 'the moles'), who excelled in many tunnelling and mining roles, the men who proved to have the most useful specialist skills were specialised engineering excavators - the so-called 'clay kickers'. The skill of many of whom had been refined in Major Norton's own engineering company. In peacetime these amazingly rugged men specialized in the digging of the sewers and underground railway tunnels in the clay which lay beneath the streets of London and Manchester. Their technique of lying on an angled board and kicking out with both feet to dig out the spoil with a spade, was perfect for the kind of mining required on the Western Front. It was a relatively quiet process that could be used in quite limited working spaces, and its progress was hard to detect by the enemy.

As the war progressed, the modus operandi of the tunnellers developed, and by July 1916 they became specialised into British 25 tunnelling companies. The Australian, Canadian and New Zealand Armies also formed Mining Corps (respectively, three, three and one tunnelling companies) that also served with distinction on the Western Front.

Tunnelling and dugouts

Since the movement of troops across open ground in daylight was so hazardous, any means of concealing it from observation from the ground and the air (balloons and aircraft) was a boon to commanders. Tunnels were dug to join together trench systems thus facilitating the forward movement of men and material. A classic example of this being the tunnels that was extended from the caves and sewers of the city Arras to the front-line on Vimy Ridge. This network of tunnels greatly aided the capture of the German strongpoint by the four Divisions of the Canadian Corps in April 1917. However, it must be noted that the Canadians were much helped in their concealment by the blinding snowstorm that met them as they emerged from their tunnels; a classic case a of nature aiding man's ingenuity.

By the same means, men and material could be protected from shellfire by the excavation of dugouts. These were underground rooms with connecting passages and were, in some locations, excavated to a quite extraordinary distance deep underground. The dugouts were intended to provide shellproof shelter for from one or two men to several hundreds. Some were dug so deep in the earth as to escape even the largest artillery and mortar shells. The Germans were by far the major exponents of the deep dugout as it suited their policy of 'holding what we have' more than it did the British philosophy of the 'continuous offensive'. Indeed, the British High Command tended to actively discourage too 'permanent' underground structures, simply because they considered this would discourage the British offensive strategy of a perpetual forging ahead to capture German occupied territory.

Some of these dugouts, particularly the German ones, were well finished with wood panelling, water pumps, electric lighting and telephones. Frequently, the company and battalion headquarters of all the combatants were located in such front-line dugouts.

Mining

Frustrated and appalled by the human cost of frontal infantry attacks on the German trenches, the British, in particular, put enormous effort into the creation of tunnels beneath the enemy lines. In these tunnels they covertly laid mines to be exploded just before the British infantry left their trenches and went 'over the top' to attack the German lines. Theoretically this should destroy the German fortifications, kill, disable or demoralise the defenders, and facilitate the advance of the British infantry.

In this ancient mode of warfare (which originated as far back as the 14th Century with the undermining and mining of castles) were engaged the Specialist Tunnelling Companies of mining engineers and, as stated previously, specialist miners who could undertake this skilled, dangerous and often exhausting work. The evacuation of these mining tunnels often took months of unrelenting effort with the continuous threat of discovery and 'neutralization' by the enemy. Both sides assiduously maintained counter-mining squads with the express purpose of the detection of the tunnels and their destruction along with the miners working in them. On occasion violent hand-to-hand combat took place underground between the miners of the two sides.

The more renowned of these tunnelling efforts are those which took place in 1916 at the Somme, in 1917 at Arras and, perhaps, the most famous, those in the Messines Sector. The Messines complex of tunnels stretched in a eight and a half mile (14km) arc from Hill 60, in the north, to Ploegsteert (Plug Street) Wood in the south. It was the original idea of Major Norton, although he had already left the tunnelling force before the explosions at Messines took place. In all, the Messines mines contained around 500 tons of high explosive.

The Arras tunnelling and mining has already been mentioned.

On the first day of the First Battle of the Somme - 1st July 1916 -the mines that exploded under the German fortifications and redoubts formed huge craters. The most prominent of these craters were, and still are, known as the Hawthorn Crater [2] (named after a German strongpoint between the villages of Beaumont Hamel and Serre) and the Lochnagar Crater [3] (located near the village of La Boiselle). Most of the other craters on the Western Front have now been filled in.

There is some debate just how many mines there were in the Messines Sector and how many exploded on the first day of the battle, the 7th June 1917. There is also uncertainty about how many mines exploded later on, and which mines still remain unexploded today. What seems to be the authoritative consensus derived from British Second Army files held at the National Archives at Kew is as follows: 12 tunnels and 25 charge chambers were dug; 19 mines were exploded on the first day of the battle (although 21 firings were planned); one mine was lost due to flooding; one tunnel was discovered prematurely - at Le Petit Douve Farm - by the Germans; and four mines in the Ploegsteert Wood area were 'kept in hand' for operational and tactical reasons. Apparently, in the chaos of war, the locations of the four unexploded mines were lost. One of them was 'discovered' by a lightning strike in 1955, and exploded fairly harmlessly. So, three mines remain lost to this day.

It is extrapolated that the 19 mines that were exploded simultaneously at 0310am in the Messines Sector on the 7th June 1917, killed a total of 10,000 Germans, with another 7,000 taken prisoner. The shock waves from these explosions were strongly felt in London, throughout the southern counties of England and, it is said, as far away as Dublin. If the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, were asleep in his bed in Downing Street, it would have probably woken him up!

The history of one of the Messines mines, the largest, is typical. The mine at Spanbroekmolen had been under construction officially for 18 months, i.e. January 1916, although preparatory work began in 1915. It was located at a depth 88 feet (27m) and contained nearly 41 tons of high explosive. The effect was so devastating that a crater 40 feet deep and 250 feet in diameter was created. Everything within a radius of 215 feet of the centre of the explosion was totally obliterated. This crater, which filled naturally with water, was purchased in 1929 by Lord Wakefield to be held in perpetuity. It was dedicated in 1932 as 'The Pool of Peace' of the Western Front.

The principal high explosive used in all these mines was a British invention called ammonal - a mixture of ammonium nitrate (3 parts) and aluminium (1 part) = AMMO+N+AL. For the main part, the ammonal was sealed in steel drums to facilitate its transport and to protect it from the wet.

By the time of the firing of the Messines mines in July 1917, the British employed 3,000 men in the tunnelling and mining work on the Western Front. These men came from Britain, Australia and Canada. They usually worked in teams of twelve under a NCO. Three of the team was the tunnel-face workers. The 'clay kicker' worked his spade at the tunnel face whilst another tunneller shovelled the clay into a sandbag or other suitable container. The third tunnel-face man carried the spoil back to a small trolley mounted on rails, where another three men of the team transported the spoil back to the tunnel mouth for disposal by two others. The final member of the tunnelling team operated the air pump that was essential to maintain a fresh, clean, flow of air to the men working at the tunnel face: An exhausting task for an eight hour shift and, later, an electric pump took over the job. Mice and canaries were used in the traditional way to warn of gas, principally carbon monoxide.

Working conditions

The conditions under which the men worked varied enormously.

In the Somme Sector it was mainly chalk, often friable, though sometimes requiring hard digging, but with little problems of drainage. This was due to the relatively elevated and graded topography of the Somme battlefield - once the excavations were away from the river valleys (the Somme and the Acre).

In the Messines Sector conditions were much more difficult. The ground was stratified into three layers. The upper layer of sandy soil covered a morass of quicksand and shale, under which lay a thick band of clay. Most of the tunnels had to be shored up with timber and/or lined for their whole length. As mentioned above, one of the Messines Sector tunnels became so affected by flooding that it had to be abandoned.

The tunnelling squads worked 24 hours a day in three shifts. The shift pattern was three working shifts in 48 hours, then 24 hours off-duty.

The effects on the course of the War of the enormous effort put into tunnelling and mining by British is impossible to determine; it is reported that a total of 3,000 miles of these mining tunnels were excavated during the Great War. Though it has to be said that the operational opportunities offered by the highly successful British mining operations on the German defence works at the Somme in 1916, and at Messines in 1917, were not properly exploited by the British to the extent they could and should have been. Certainly, the awareness by the Germans that the British were vigourously engaged in tunnelling and mining activities must have added to the already considerable nervous stress they were under.

Finally, a question that must be asked is why didn't the Germans themselves, as early starters at tunnelling and mining, engage in it more actively as the War ground on? (It is recorded that on the Western Front in June 1916, the Germans actually fired 126 mines against the British total of 101). Certainly their mastery of all aspects of the technology of war was generally superior to that of all the Allies. Surely, we can't suppose that the lack of the equivalent of the British clay-kickers was the deciding factor? Perhaps, the question may be answered by the fact the British didn't have such a penchant for building strong points and redoubts, as did the Germans. It is not debatable that for the British the German strong points and redoubts offered excellent targets for tunnelling and mining. But, equally, it must be questionable that the Germans could have justified such expenditure of manpower and material on the much more modest pickings that say, a hundred yards of a typically modestly fortified British trench system would offer.

Conclusions

Whatever was the rationale for, and the strategic effect of, the extensive mining and tunnelling that took place on the Western Front in the Great War, there still remain on the old battlefields a few of these formidable craters that have not been filled in. We can only view them and be amazed at the energy, determination and dedication that went into their creation, and the stoic resistance shown by those who survived the maelstrom of their man-made eruptions. We must also congratulate those who by their foresight and action have ensured that at least some of the bigger mining craters have been preserved in perpetuity.

References

[1] The terms used with respect to tunnelling and mining on the Western Front can be confusing to the reader: Tunnelling = Boring and digging holes more or less horizontally; Mining = 1. Digging and boring holes, and, 2. Placing and firing explosives. In this article we have used Tunnelling = Boring and digging holes, and Mining = Placing and firing explosives.

[2] The explosion that created Hawthorn Crater was recorded on ciné film and was shown to huge cinema audiences in Britain, and abroad, as part of the 1916 film 'The Battle of the Somme'. It is commonly reproduced in photographic stills of the Somme and the Western Front and has been frequently shown on TV in programmes about the Great War.

[3] The Lochnagar Crater is the largest on the Western Front; the size of explosive charge used was 25 tons.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

The WFA regularly makes available webinars which can be viewed 'live' from home. These feature expert speakers talking about a particular aspect of the Great War.

Featured on The WFA's YouTube channel are modern day re-interpretations of the inter-war magazine 'I Was There!' which recount the memories of soldiers who 'were there'.

Explore over 8 million digitized pension records, Medal Index Cards and Ministry of Pension Documents, preserved by the WFA.

Other Articles