Vaterland

She was the largest ship afloat And was the bejewelled seagoing delight of all Germany, a not to be forgotten colossal luxury liner that was a symbol of glittering national power. Yet the Vaterland was to serve only the Americans in the Great War. Some may ask "Whatever happened to the Vaterland?"

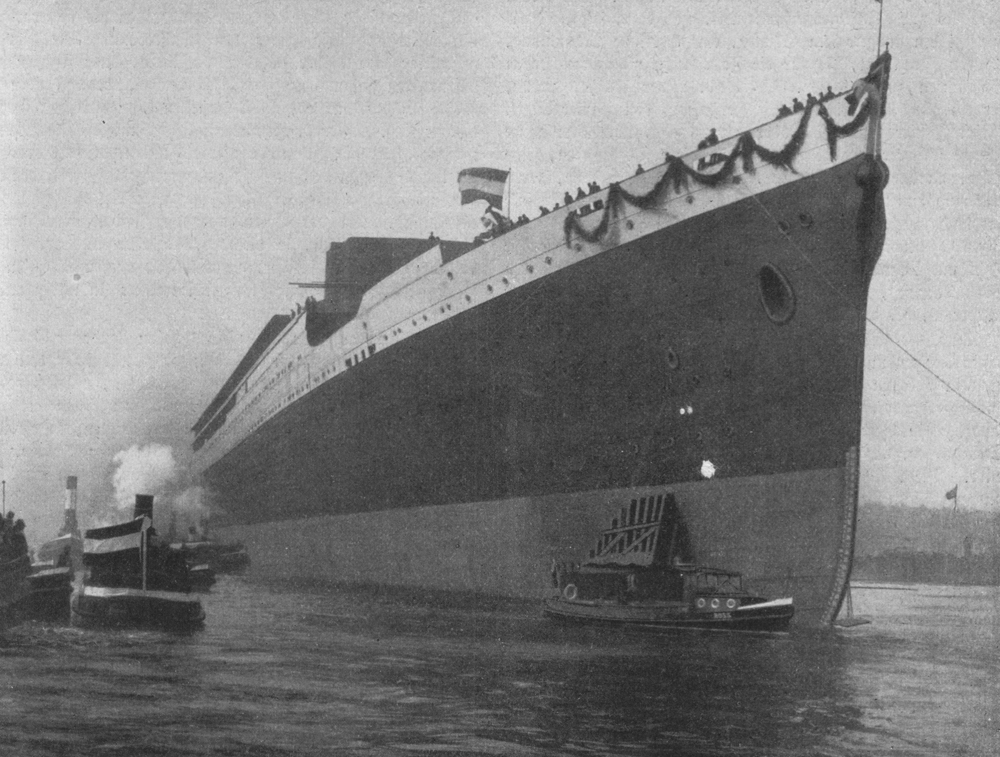

Everything about her seemed to be enormous, perhaps out of scale, on the large side for the times She was constructed by the famous Blohm & Voss yard in Hamburg for the Hamburg Amerika Line and launched for trans Atlantic passenger service on April 3, 1913 Nothing like it had been seen before. The ship had an impressive displacement (weight) of 54,282 gross tons, an overall length of 907 5 feet and a beam of just over 100 feet. Her top speed was 22.5 knots. The commercial crew numbered 1,120.

Vaterland was not built for war duty, but was the second of three large, fast, and luxurious express steamers designed to compete with British liners then coming into service when her keel was laid down, most notably the White Star Line's Olympic and Titanic In fact, Mr Albert Ballin, the prewar director of the Hamburg Amerika Line, was a staunch antimilitarist who believed that the only conflicts that Germany should be involved in were commercial ones

This brand new superliner had three funnels (the farthest aft was a dummy), tall masts fore and aft, four huge screws, and a clipper style stern This imposing German ship was powered by direct acting steam turbine engines geared to quadruple screws; these were far more economical to operate and maintain than conventional reciprocating engines and were very fast and dependable in almost any weather for the New York shuttle. And that proved to be true on her maiden voyage in May 1914 when Vaterland made a steady 22 knots from Hamburg to New York, with none of the vibration and mechanical problems that had plagued the first voyages of other Hamburg Amerika Line vessels.

The accommodations were richly appointed in keeping with the best liners of the day. First class cabins, for the first time, had hot and cold running water Public rooms may properly be described as plush, even extravagant Passenger service was attentive and unflawed. Upper deck guests could perambulate as they might at home. There were accommodations for 750 First Class passengers. 535 in Second Class, 850 in Third Class, and 1,536 in Fourth Class She was greeted ceremoniously and warmly on her arrival in New York by distinguished dignitaries, elected officials, throngs of wide eyed spectators, cabbies by the hundreds, two bands, and crews of dock workers ready to turn Vaterland around for her first eastbound express crossing The reception that followed was a social top of the season affair This ultramodern vessel would be a commercial success and further help to tie two continents together

Vaterland made two more Atlantic crossings, with full loads of passengers going both ways, but by the tune of the June 28. 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, dark clouds forewarned of foul weather yet to come. Captain Ruser was ordered by Director Ballin to keep the crew at the highest level of readiness and be prepared to take evasive action against enemy warships, knowing that an outbreak of war could mean the destruction or confiscation of the grand ship The ship ran into mechanical problems on her fourth crossing that forced the closing down of one of the four turbines and its propeller. Speed was sharply reduced Then the failure of all four of her backing turbines made her completely dependant on tugs when entering the harbor and docking in New York City It was because of the ship's newness, but was, nevertheless, somewhat embarrassing.

As it happened, when the pilot came aboard on July 29, 1914 to manoeuvre the slow moving Vaterland into its berth, he passed by several senior officers who had taken a huge portrait painting of the Kaiser off the wall and destroyed it, fearful that it was he who would take their lovely ship away if war were to be announced And this was with some justification because war had been declared a few days later between Germany and Britain and the United States government moved on August 4, 1914 to intern Vaterland Perhaps this was a saving measure for the ship as British warships were patrolling just off the New York coast. But this also marked the end of German ownership. This giant symbol of a modern Germany was to rust away slowly for the next three years at her pier, manned only by a small skeleton crew. There she stood as a shadowy, massive hulk, with her glory hastily slipping away.

But this was not the end of that greyhound of the seas On April 7, 1917, the day after the United States entered World War I, the Vaterland was seized by Federal agents. backed by armed soldiers Immediately, a rift between the United States and the British Admiralty ensued The U S Navy was stunned when the British refused to allow the extremely large ship into the Liverpool or Southampton harbours, stating that it would overtax harbour facilities and if it were to be sunk or damaged during arrival or departure it could close the ports to other ships It was suggested that Vaterland be used as a hospital ship by the Americans between some unspecified European port and the United States

Captain Albert M Gleaves of the U S Navy was the first to see the potential of Vaterland as a troopship before the war started. He was present at the arrival of the ship in New York City on her maiden voyage and had asked one of the senior officers how many troops the liner could carry in wartime "Seven thousand," he said, "and we built her to bring them over here". Gleaves, not missing a beat, answered "And when they come we shall be happy to meet them." But now, Gleaves, a full admiral and Commander of the U.S Navy's Cruiser and Transport Force, tactfully argued that the largest ship afloat would be misused as a hospital ship when it was vital to the support of the war to carry American troops to Europe. Finally, the Admiralty agreed that the speedy Vaterland would best be used as a troop ship and the U.S. Shipping Board passed control to the U S Navy in June 1917

A survey of the ship found that the years of sitting idle had quite significantly deteriorated the turbines, boilers, auxiliary machinery, and pipes. Vaterland 's bottom was anchored to the muddy harbour floor by massive growth of barnacles and the build up of silt Within days of the survey, the navy moved quickly to recondition the famous liner, even without detailed engineering drawings Navy teams were able to bring the boilers and turbines back on line. Replacing piping and relocating much of the electrical system were more difficult tasks At the same time, other crews were removing most of her civilian furniture and fittings and sending them ashore for storage Carpenters and pipe fitters began to install thousands of troop bunks. Kitchens and food storage areas were enlarged To conserve fresh water during troop sailings. faucets were removed from all accommodations except the staterooms assigned to the captain, the executive officer, and the commander of the embarked troops (regardless of the fact that the distillation plant was capable of producing 24,000 gallons of fresh water per day) Interior spaces were scrubbed, fumigated, and disinfected.

Outside Vaterland, the ship was found to be solidly aground in the silted mud The Army Transport Service brought in dredges to shift the silt and, guided by the divers, the dredges were able to free the hull in four days of non-stop work The liner was now ready to be dry-docked, but there was no dry-dock in the U.S that could handle her size. Finally, after considering sending her to a suitable dry-dock in Panama (but the canal was closed due to a rock slide), navy divers dud the best they could to scrape off the layers of barnacles, while Britain agreed to dry-dock the ship at Liverpool for proper scraping and painting alter Vaterland 's first eastward crossing

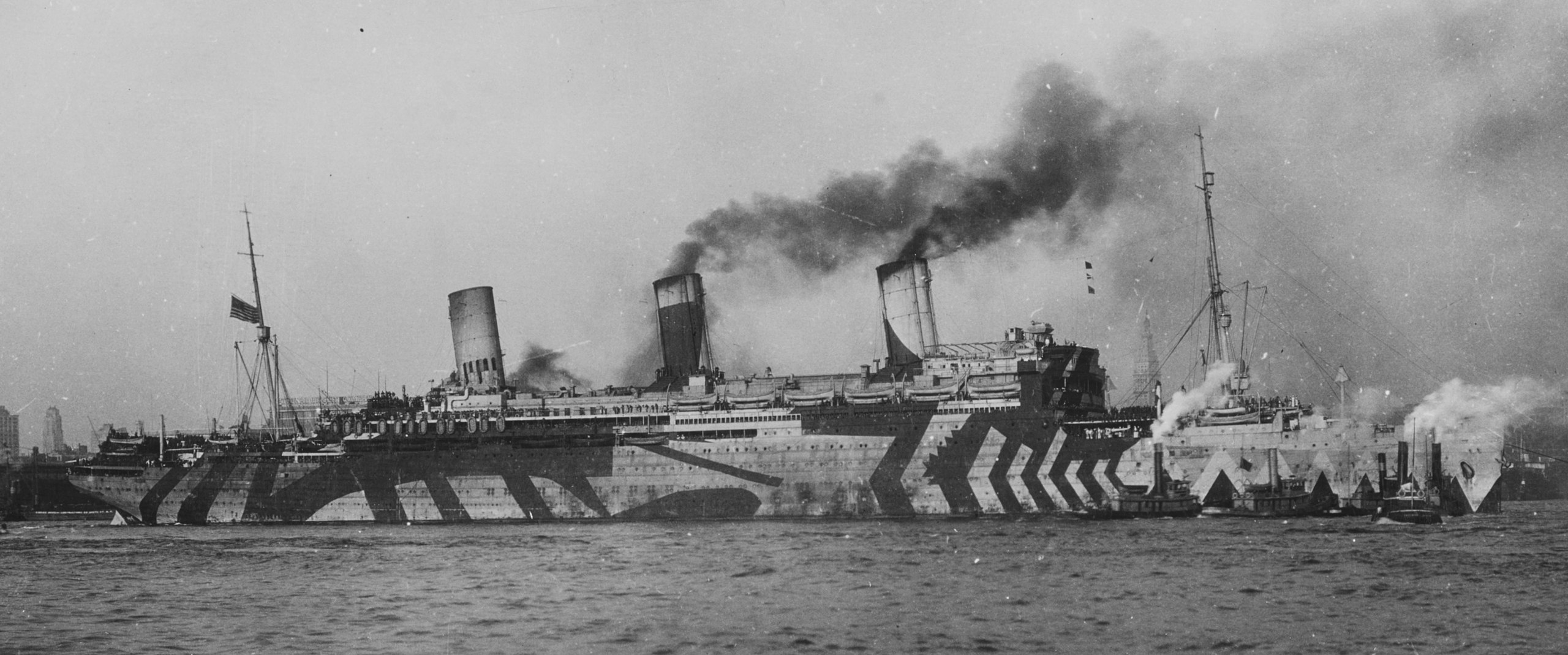

The conversion was almost complete by midsummer and the vessel was commissioned into the United States Navy on July 25,1917 under the command of Captain J W. Oman. By the time the ship was crewed with 2,000 navy sailors, the once magnificent liner was renamed USS Leviathan on September 6, 1917, according to Frank Braynard' s monumental five volume work The World's Greatest Ship, The Story of the Leviathan. The name means "sea monster" in various scriptural accounts. After a trial run from Hoboken, NJ to Cuba and back, armaments were installed (eight inch guns, two one pound cannons, two 30 calibre machine guns and a central magazine made from one of her cargo holds). At the same time, the ship received a dazzle paint scheme in an effort to confuse any U-boats who might sight her at sea, like those being applied to many Allied warships, which she now was.

Coaling and provisioning were underway on December 11, 1917 and 7,250 U.S troops began to board The tugs eased the vessel away from the pier four days later and Master Pilot Captain William S McLaughlin, aware of her deep draft and the distinct possibility of grounding, eased her slowly to open water She became a genuine trooper quickly, running at full speed on the northern circle route to Britain Lookouts were doubled and soldiers lectured on safety at sea On Christmas morning, 1917, the mighty Leviathan sailed into Liverpool's busy wartime harbour and to some on shore and aboard ships in the harbour, she looked to some extent like a sea monster. Thousands of hat waving Doughboys, who called the ship "Leviathan", were anxious to disembark Somewhere a military band blasted out "Over there".

Leviathan now had to wait until a spring tide high water range, on the full moon, to clear the sill of the dry-dock, so deep did she lay in the water. Once carefully eased inside the walls of the mammoth dry-dock, bottom work began and workmen began to install 1,000 additional bunks On February 19, 1918 the trooper took to sea, making New York City nine days later After discharging more than 1,000 injured soldiers and numerous diplomats and officials transported from Liverpool, the ship was again cleaned and fumigated, fresh water tanks replenished, her refrigerators filled, and coal barges pulled alongside to begin filling her enormous bunkers. Yet again, carpenters scrambled aboard and this time installed 650 additional bunks, raising the steamer's troop capacity to 8,900 The first soldiers arrived from New Jersey staging camps on March 1, 1918 and three days later Leviathan slipped out to sea at night with a another full "passenger list".

She arrived in Liverpool eight days later Returning hurriedly westward the former liner was back once more in Hoboken on April 17, 1918 ready to embark more American regiments. It was clear after two round trips that Liverpool Harbour was insufficiently deep to accommodate the trooper. The Leviathan departed for its new French port of disembarkation on April 24, 1918 and she was back in New York on May 12, 1918, cutting her turnaround time from 54 days to 26 days. could only enter the harbour during the high tides of a full or new moon, she was thusly able to make only one round trip during every two lunar months This sharply limited the Allies' largest and most capable troop carrier at a critical time in the war. Gleaves suggested that the troop ship be routed to the deepwater port in Brest, France which was not affected by tides. Moreover, coal could be shipped to Brest directly for re supply. And by eliminating Liverpool, the troops would not have to be trans shipped to France as they might be disembarked close to their camps in France Wounded soldiers and others on official business could also board straight away in France The Navy Department and the British Admiralty agreed with Gleaves' suggestion The ship's troop capacity was now increased to 10,500.

As the troop carrying capacity grew, the crew was constantly refining its ability to cope with the number of people involved A complex yet efficient system evolved to govern the care and feeding of the embarked bored troops This system controlled every aspect of shipboard life, dictating when and where the crew and soldiers slept, where and when they could relieve themselves, where they could smoke, and when and how much they ate. The ship always tried to run at a full 22 knots and in any kind of weather, thus seasickness could become a terrible problem. Lifeboat drills were a way to exercise the men, but there was no where near the number of boats or rafts needed to save the troops, and the boats were located on the upper decks, where the first class passengers used to dwell.

Feeding more than 10,000 men well, it was discovered, was critical to their morale, and thus discipline. Ordering food was important For example, it took 250,000 pounds of fresh and canned meats, 25,000 pounds of fresh poultry, 360,000 eggs, 200,000 pounds of flour, and 595,000 pounds of fresh vegetables and fruit for each eastbound voyage Add to that many thousands of gallons of fresh water, milk, coffee, tea, and fruit juice Besides 10,000 soldiers, there were also 1,800 navy crew members to feed Every time that the soldier carrying capacity was increased so was the need for more refrigeration, large electric ovens, automatic dough mixers, heavy-duty steam kettles, and so forth. All cooking was done in the first and second class galleys, drawing work parties from the troops aboard.

Serving food also required continually supervised arrangements While officers sat at cloth covered tables on the upper level of the first class dining room and were served by white uniformed waiters aboard Leviathan, enlisted personnel ate standing up as they filed slowly through a lower level mess hall Troops and crew members entered via the Grand Staircase, at the base of which were 12 serving stations, and cleaned their trays and utensils at stations set up just inside the exit doors They then returned to their assigned work stations or berthing areas. This system allowed the kitchen staff to serve about 11,000 soldiers in 75 minutes It is understandable why thousands of enlisted men were enthusiastic to get off the crunched and odorous trooper as quickly as possible. This was not to be one of the ocean liner cruises that they had read about or otherwise envisioned.

Packing such large numbers of troops aboard Leviathan was a calculated risk because a single direct hit from a torpedo could result in the deaths of several times the numbers lost on Titanic or Lusitania, but that was a risk that the army generals in the United States were willing to take because of the need for troops in France. By luck alone, not one fully loaded American trooper was lost during the war. As it turned out, the real killer aboard the Leviathan was the dreadful Spanish Influenza epidemic of 19181919, which world-wide killed more people than were lost in the Great War

The illness was especially active in troop transport staging areas It hit the Leviathan on her ninth trooping voyage, the day after she departed New York for Brest on September 29, 1918 There were 9,320 troops and a ship's company of 2,500 aboard The small ship hospital was overflowing with patients before the end of the day Many additional bunks had been filled with grotesque looking sick men and the first death occurred three days later. By the time the ship reached Brest on October 7, 1918, 93 more soldiers had died. Another 15 died after being taken ashore and 3,000 men aboard were considered extremely sick by the medical staff

Leviathan was rapidly re-provisioned in Brest and headed back to New York for another load of troops which, it so happened, was to be her final wartime voyage. Turned around and resupplied once again, the trooper departed New York for France on October 27, 1918 with 7,570 troops aboard. There were only a few cases of the flu on this trip and no deaths November 11, 1918 found the ship still in Brest, her paint mostly worn off by the seas and wind and she appeared like a true warship long in battle The army and navy planners assigned her almost immediately to assist with the repatriation of almost two million U.S soldiers, sailors and marines This was a vital assignment as virtually all of the foreign flag vessels that had transported the American Expeditionary Force to Europe were withdrawn from trooping soon after the Armistice. Now Gleaves' Cruiser and Transport Force would have to get the men home without outside assistance.

In Brest, hundreds of French workers boarded the ship to install yet more bunks, ventilators, and toilets, increasing her troop carrying capacity to 12,000. Soon, all of Gleaves' ships would be ready to be crammed with homeward bound troops. The largest ship in the world departed Brest on December 9, 1918 with 14,000 souls aboard The trooper ploughed through bad weather for most of the trip but arrived at Hoboken on December 18, 1918 to the delight of thousands of seasick soldiers whose first objective was to get off that "rocking boat" and onto solid land. The trooper made eight more round trips to France over the next 10 months carrying an average of 10,500 troops per voyage. Despite the considerable overloading, she was reasonably stable in rough seas, usually maintaining at least 20 knots Tens of thousands of restless young men waited in France to go home.

As a naval vessel, Leviathan transported 192,753 people to and from Europe by September 8, 1919 when she was withdrawn from military service, more than twice as many as America, the Force's second most active vessel. It would not be until World War II that her records would be surpassed by the Cunard Line's Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth. Her wartime service was over and she was struck from the Navy List on October 29, 1919.

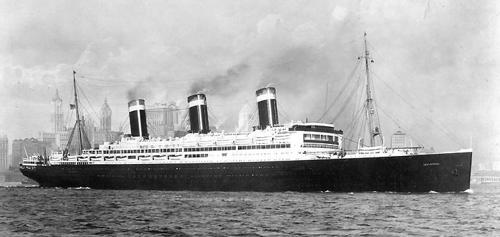

Leviathan was laid up at Hoboken for the next two years as several shipping companies wangled over her disposition. She was ultimately transferred to the United States Line and in April 1922 was moved to Newport News, Virginia for reconditioning as the flagship of the line. It took one year and $8 million to restore her to her pre-war Vaterland condition She had been converted to oil fuel in the process. The splendid liner made her first post-war commercial Atlantic crossing in July 1923 She was popular and periodic modifications to her passenger accommodations kept her profitable, even against the new post-war liners which had joined the North Atlantic passenger service She was the first to offer the fashionable Tourist Class to passengers.

By 1933, however, the United States Lines, with seemingly endless financial difficulties coupled with the effects of the world-wide depression, decided that the gigantic liner was too expensive to operate and she was laid up in Hoboken. Leviathan was returned to service for five Atlantic crossings during the summer of 1934 but that would not be enough to save her. She was again laid up in New York in September 1934. where she sat undisturbed until January 1938, when she sailed on her final Atlantic voyage to the ship breakers in Rosyth, Scotland.

Many cheerless famous people and dignitaries and a large group of reporters were aboard for this voyage to witness and document her last days. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to know about the closing stages of the largest ship afloat

By the last part of the summer of 1938. the once elegant and pompous ship no longer existed at all She had carried out missions in the Great War that her designers had never even imagined, always slicing and crashing into harms way. In the dreams of some, the tall, misty ghost of Vaterland still sails today.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.