Newcastle's Own in the Big British Advance (35th AIF Battalion)

On 16 November 1918, the Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners Advocate, a newspaper from Hunter Valley in Australia, published an account by Captain Mortimer Lyne, entitled "NEWCASTLE'S OWN - IN THE BIG BRITISH ADVANCE".

Mortimer Lyne [1] was an Australian newspaper reporter who had enlisted in the AIF in 1915, was wounded twice, and took part in the 1918 Battle of Amiens. His article is a very vivid account of the role of “Newcastle’s Own”, the 35th Battalion of the AIF [2], on the opening day of the “100 Days Offensive” on 8 August 1918 [3], and is reproduced here, in full.

NEWCASTLE'S OWN - IN THE BIG BRITISH ADVANCE

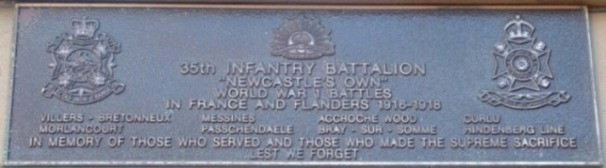

By reason of the splendid services rendered in the big German push of March-April last, the gigantic British offensive which commenced in the early days of August, Newcastle's own battalion, which belongs to the newest division in the Australian Army - a division which since its arrival in France has done magnificent work - now ranks side by side with the famous Battalions of the older divisions, and there is no one who will deny them that honour. At Villers Bretonneux, they won distinction; also at Morlancourt, and their latest enterprise, at time of writing, and to which this article relates, was the capture of Saiily and Cerisey Ridges on the 8th day of August - the day that the ball was set rolling for the British push.

For a fortnight or so before the advance was made, rumours about the coming stunt were being circulated. The battalion was out of the line, resting in a pretty little spot on the banks of the ----- River. The news came late one afternoon, and at dusk the battalion was on the move forward. No definite information was obtainable, but everyone knew that something was going to happen. We marched a few miles that evening and halted at another position on the same river to await events. Preparations for a fight were made, ammunition, bombs, etc., issued, and everything made ready to move up. We remained here for several days, and so secret was everything kept that it was not until the last day before moving out that the men were informed what was happening. The approach march that night was a long one, but there was not a grumble from anyone. Everyone felt that the operation was going to be a success, and they longed to get at the Bosch and give him something that he gave us in March. All ranks knew that there were going to be lots of tanks assisting in the operation, and the thought of tanks instils confidence in anyone. Moreover, we were told that the barrage was going to be the biggest yet undertaken, and the whole operation was to be the greatest yet performed by the British throughout the whole war.

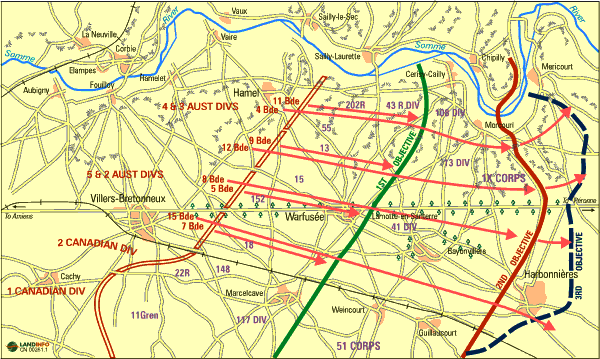

Our battalion – the gallant Newcastle's own - was to play a leading role in the enterprise - it was to form the first and second waves, with the British on its left and the Canadians on its right, and the French and Americans on the Canadians' right, so no wonder were tremendously enthusiastic for the fight. The approach march was quite uneventful. When nearing the front line, a few machine gun bullets coming from the direction of Accroche Wood, which was just to the right of our sector, whizzed over us, but nobody was hit. Coffee was served out, before moving up to the jumping off tape, which was a great luxury after the long silent march from the rear. There was almost an hour to elapse before zero after the battalion had taken up its position, ready to hop over. The night was clear and peaceful as any night might be in any peaceful land under the most ideal climatic conditions. A few shells were exchanged and every now and then a "Very" light would spurt up into the sky and light up the land in its vicinity, but there was nothing to show that the enemy had any idea of what was very shortly to happen - in other words, conditions were apparently quite normal. As we waited on that tape line, one could not help thinking that here we were, the armies of the Allies, concentrating in thousands, for one of the mightiest undertakings of the war, within a few yards of the German lines, and on a front of about eighteen miles, and yet the enemy knew nothing about it. From our position where we stood, we looked down upon the Bosch's front line. We knew we would have to negotiate a valley as soon as the advance commenced; we knew we would have to pass through the left of another wood, and pass over two ridges before getting to our objective, which was about 6000 yards behind the enemy lines, and we also knew that the last valley - that separating Gailley from Cerisey Ridge - was likely to have some artillery concealed in it; but beyond that we knew nothing, except, of course, that we had to get to the position.

The tanks were the first to break the silence. We could hear them moving up into position, and our blood curdled in fear that the enemy would hear them also, and that the show would be betrayed. The noise of a tank is similar to that of an aeroplane, but nothing happened. "Zero" hour was at 4.20am. The night was beautifully clear and starlight; in short, the conditions were ideal for operations of this sort. At five minutes before zero, something was happening where the tanks were in a valley on our left. Explosion after explosion burst out, the flashes lighting up the darkness, and we wondered at its origin; but we did not wonder for long, our musings suddenly being interrupted by the commencement of the barrage. It seemed to open from the left and, in an instant, everything was like an inferno. The rain was awful. The stunt had started, and we commenced to move forward. Before we had advanced thirty yards a dense mist developed, which blinded us all. Before the bombardment there was not the slightest sign of mist but, as soon as it commenced, it was as thick as mud. So absolutely impossible was it to keep touch, that companies, platoons, sections, and individual men at once became detached. You could not see more than a yard in any direction. Officers yelled to their men to follow them, but the men could not see their officers – everyone, more or less, as they moved forward, were like blinded men groping about guideless.

The awful bombardment, the enemy shells falling in amongst us, and this horrifying mist, was enough to frighten anyone, but these Australians knew there was only one thing to do - to go forward - and go forward they did. Men without officers led themselves until picked up, as the stunt proceeded. Officers collected those men scattered round them, and led them on, calling out to others who might be near, and whom they could not see, to follow. Battalions got mixed, companies got mixed, everyone got mixed, but still they went on, with a determination to do their damnedest against this unscrupulous foe, and to thrash him out of the place. There were many tanks operating with the infantry - three per company was the original plan, but the noise of their engines was deadened by the terrific row of the guns and shell explosions. Right into this first valley, leading to the German front line system, the Australians moved. They did not rush - they could not because of the mist - they simply moved forward into the unknown, not knowing when they would step on to the enemy, and what danger they were walking into. That did not trouble them. They wanted the Bosches.

The scene in that valley was awful; shells burst everywhere. Men fell over, and into, the shell holes, but they remained undaunted and resolute, determined upon carrying out the job. Though the country over which we were passing had been studied beforehand, by means of maps and aerial photographs, it was impossible to recognise the features. We passed over two lots of trenches, which we took for the British and German front lines. Here it was expected that opposition, in the shape of machine guns, would be met, but what opposition there was, was soon disposed of. Our fellows were too quick for the Hun. He was as much hampered by the mist as we were. He could not see us any more than we could see him. The noise of a machine gun only betrayed their position, and the gunners were quickly put out of position. There were many Germans in these trenches and most of them were only too glad to surrender. " Come out you ------!" yelled our fellows, "Come out of that!" and out they would pounce from everywhere, crying "Mercy Monsieur," "Mercy Kamerad," with their hands stretched up into the air. Most of them seemed mere boys, though a fair percentage were decent aged men. They all looked terrified, as they must have been, for our barrage had just passed over them and the wonder was that any of them were left alive.

One officer was leading his men, or rather a collection of men, for they were not his own, he had picked them up on the way over and he suddenly came on to a machine-gun post. Whilst he was debating how to deal with the situation, a Lewis gunner crept up with his gun and, putting his gun in position, waited his opportunity, and fired a burst. We then went forward to see the result. The result was there all right, for the gun teams - there were two guns - lay dead at their posts. Machine guns were captured everywhere but, each time a gun was met, the gunners fought to the last. That is one thing I'll say about those German machine-gunners - they fought and died like soldiers. To my knowledge not one Hun machine-gunner surrendered. They used their guns until they were shot at their posts. One batch we came up against had their guns - about eight of them - placed in an open field. We did not know they were there until nearly onto them. Then they opened fire. We dropped for cover, and engaged them. After their guns had been silenced we went forward to ascertain the result and, to our astonishment, found eight guns, with their teams of two men, dead or dying at their guns, and the guns placed absolutely out in the open. Those men were brave men, and one could not help recognising the fact at the time.

The tanks played a gallant part in the operation, but they, like the infantry, got lost in the mist. Like the infantry, for the most part, they too were forced to depend on the compass for direction. Personally, I only saw one tank throughout the fight. I heard another away in the mist but I did not see it. The tank I did see, though, performed a wonderful feat in front of our eyes. We had just disposed of those eight machine guns, when this tank, wearing our battalion colours, hove in sight. The tanks detailed to wait with the various units wore those units' colours, which was a useful idea, because it enabled the men to distinguish their own from other battalions' tanks. I rushed across to stop the tank to discuss the situation. These tanks are wonderful things. If you want to go up and talk to the officer-in-charge you run up and ring a bell. The officer inside opens a little trapdoor and puts his head out, or if that is not good enough, he opens the main door and steps outside. On this occasion, he stepped outside and shook hands, and this on the battlefield. While he was talking, some shots came our way from the slope of the ridge - Cerisey Ridge. We were then in the valley, where we expected to capture artillery generals and colonels with all their guns, but they were not there when we arrived - they had gone. We got plenty of machine guns though, and a few field pieces, including a "five-nine" gun and a "whiz-bang" gun, and any returned soldier will tell you what they are. The infantry commenced to fire at the ridge, but the tank commander, after surveying the place, said calmly - "Wait a minute boys, I'll find them," and got inside his tank and shut the door behind him. With a grunt and a bit of a shuffle the tank commenced to move, while the infantry placed themselves in the rear in skirmishing order. The officer inside put his tank broadside on and commenced to fire at the slope with his gun. He soon silenced the Bosches, and he then directed his attention to the dugouts on the side of the hill. Shot after shot rang out, and he was making direct hits on to the dugouts to the great amusement of the soldiers walking behind. The Huns could be seen on the hillside, but this tank officer gave them no quarter. Dissatisfied at being farther away than he wished, he put his tank to a very steep embankment to enable him to get up on to a road which ran round the ridge about half-way up. We did not think it possible for him to negotiate this steep incline, but he climbed it as easily as falling off a log - easier than we did ourselves in fact. Again he started pounding away until all opposition was swept aside.

It was a great day that day, and one never to be forgotten. Despite the fact that everyone was more or less lost owing to the fog, the objective was reached only shortly after the scheduled time, though men roamed in from all directions for an hour or so afterwards. The C. O. Battalion was on the objective soon after his men had reached it, and no one was more surprised than he that anyone had got there at all. Those who were not in the show can have no conception how difficult it was to maintain directions. The barrage was little guide because, for the most part, it was fired obliquely. The compass was really the means of getting there. The captures were enormous. Hundreds of prisoners were taken, many Bosches killed, and hundreds of machine guns fell into our hands. The battalion consolidated its position. The tanks rested in the valley behind, and the artillery bombarded the area in front of us, preparatory to two more Australian divisions continuing the advance two hours afterwards. They passed over our lines according to plan, and pushed on, gaining their objectives, and establishing their line 6,000 yards in front of where we stopped. They captured enormous stores, guns, machine guns, hospitals with all their personnel, including nurses, and God knows what. Immediately after they advanced, the artillery moved up and went forward of our position on Cerisey Ridge. Balloons came up, transport, lines and lines of infantry - everything to complete the organisation of the advancing army. It was a magnificent sight - a real open warfare spectacle, and the first of its kind during the whole war. [4]

The spirit of the troops was high. They were keen to go on, and many a Newcastle lad in that battalion of the same name held upon its objective were disappointed at seeing men of other divisions passing over them, and they were not permitted to go on and finish the job. Their behaviour was all the more magnificent, because a big proportion of the lads were reinforcements, and they had never been in the line before. All officers agreed that the new men behaved splendidly, and did very fine work. One officer, whose platoon was composed almost entirely of new men, gave orders that no prisoners were to be taken. The men, of course, as soon as the advance started became detached. One youngster picked up with another battalion officer of the battalion and, when they came upon a nest of Huns, this lad commenced to shoot them down right and left. The officer rebuked him, and asked him what he was doing killing all the Huns and not taking any prisoners - one does not like to kill in cold blood. "Oh," said this boy, "our officer lectured to us before we came into this stunt, and told us we were not to take any prisoners, and I'm simply obeying orders." That was the spirit with which our fellows were imbued that day, and they did remarkably well. We were not troubled by Hun planes. The British have had the superiority of the air for a long time now and, on the memorable 8th of August, which should be a day always to be remembered by Newcastle people, in view of the gallant work rendered by its sons and the glorious victory achieved, there was not an enemy 'plane in the air. Only in the afternoon did the Huns dare to show their heads, and nearly all of them were brought down.

References:

1. Mortimer Eustace Lyne was born 4 October 1891 in Waratah, New South Wales, Australia. He was a 24 year old journalist who worked as a newspaper reporter at the Evening Penny Post in Goulburn, N.S.W prior to enlisting in the 35th Battalion, AIF, in 1915. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1917 and wounded (a severe gun shot wound to the right eye) at the Battle of Messines. Returning to the Battalion in February 1918, he was wounded a second time in June (gun shot wound to his right leg) at Villers-Brettonneux. He returned to the Battalion in July and was promoted to temporary Captain. He survived the war, married in 1923 and lived until 1964. (All information courtesy of The Harrower Collection - https://harrowercollection.com.au)

2. "Newcastle's Own" referred to the 35th Battalion, an infantry battalion raised in the city of Newcastle, New South Wales, from local volunteers. The battalion was formed in late 1915 as part of the expansion of the AIF after the Gallipoli campaign and served on the Western Front. It was part of 9 Brigade 3rd Division AIF.

3. 8th August 1918. This was the first day of The Battle of Amiens, the opening phase of the Allied offensive which later became known as the Hundred Days Offensive, and which ultimately led to the end of World War I. Allied forces advanced over 7 miles on the first day, one of the greatest advances of the war, with Gen Henry Rawlinson's British Fourth Army, with nine of its 19 divisions supplied by the fast-moving Australian Corps of Lt General John Monash and Canadian Corps of Lt General Arthur Currie, and Gen Marie Eugène Debeney's French First Army playing a decisive role. The battle is also notable for its effects on both sides' morale and the large number of surrendering German forces. This led Erich Ludendorff to later describe the first day of the battle as "the black day of the German Army". Amiens was one of the first major battles involving armoured warfare.

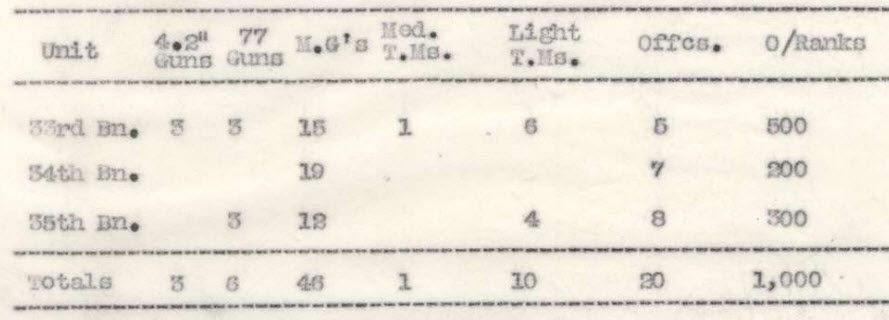

4. According to the War Diary, the 35th Battalion captured 3 x 77 Guns, 12 MGs, 4 MGs, 8 officers and 300 men.

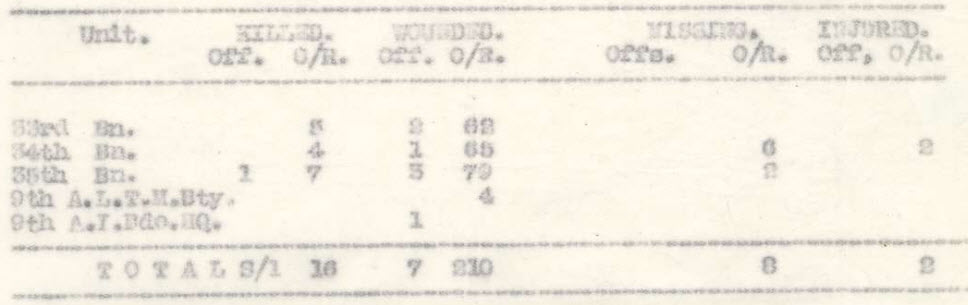

On this day, they lost 1 officer 7 men (killed), 3 officers 79 men (wounded), 2 men missing.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

The WFA regularly makes available webinars which can be viewed 'live' from home. These feature expert speakers talking about a particular aspect of the Great War.

Featured on The WFA's YouTube channel are modern day re-interpretations of the inter-war magazine 'I Was There!' which recount the memories of soldiers who 'were there'.

Explore over 8 million digitized pension records, Medal Index Cards and Ministry of Pension Documents, preserved by the WFA.

Other Articles