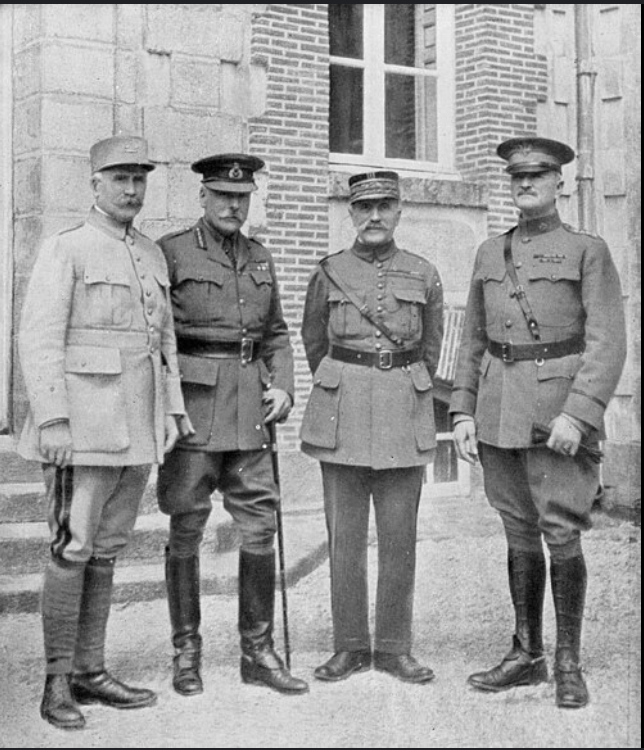

Prominent French Commanders on the Western Front

Apart from some brief secondment to other theatres of war, such as the Italian Front, and diplomatic missions related to the war, all the senior French Generals and the Marshals spent the Great War on the Western Front. Indeed, when General Robert Nivelle's much vaunted Chemin des Dames Offensive of 1917 failed, his assignment to the French colonies in North Africa was seen as both punishment and the path to professional oblivion.

The eight French Generals and Marshals who are considered here, were all born in the seven-year period 1849 -1856; Galliéni was the eldest. All were too young to have a significant role in the 1870-1 Franco-Prussian War, the humiliation of which changed the whole psyche of the French nation about national sovereignty and the role of the military in its preservation. This was particularly so of the officer corps, but over time this attitude influenced nearly all of the military and civilian populations.

One of the first steps taken by the French Government after the Franco-Prussian War was the institution of Universal Military Service. By 1914, the terms of service had been extended to cover 'All fit men between the ages of 20 and 45' who served three years with the colours, 11 years with the reserve and the remainder with the Territorials. Selected soldiers were permitted to re-engage for 15 years under improved pay and conditions. These re-engagés subsequently formed the majority of the NCO cadre. This system brought the number of men (including officers and 46,000 colonials) available for mobilisation in August 1914 to 3,780,000. The figure mobilised for the entire war was 8,317,000 of which 475,000 were colonials.

The French officer corps were trained at military colleges: St. Cyr for the infantry and the cavalry, and L'Ecole Polytechnique for engineers and artillerymen. There was also a staff college for senior officers called L'Ecole de Guerre. About one third of the officer corps in the Great War were commissioned former NCO's.

The military philosophy that dominated the learning at these military schools, and thus throughout the French Army, was stated as 'The French Army returning to its traditions, henceforth knows no law but the offensive.' It was also expressed as: 'L'attaque [or L'offensive] à l'outrance.' (Always immediately counter attack); 'L'audace, encore l'audace.' (Be daring, again more daring, always daring) and 'L'élan vital.' (The vital impulse [to fight])

It was this dedication to the offensive stance in all situations that led to the famous élan (dash) of the French infantry. It was also the genesis of the tremendous numbers of casualties that were incurred in the first few months of the war (almost a million, with 300,000 killed, by the end of 1914). A series of further horrendous casualty figures led up to the mutiny of some units among the French Army's Front Line troops in 1917. The breaking point of the French soldiers was said to have been largely induced by the heavy, irrational, losses of the Nivelle Offensive.

The French Generals and Marshals of the Western Front

Two Marshals clearly top the list: Foch, and Joffre - and two more dissimilar soldiers in form and modus operandi would be hard to find. A third, Pétain, is impossible to ignore as he was very close to this level of distinction on the Western Front no matter what happened later in his long life. The remaining five all have claims for distinction in various ways.

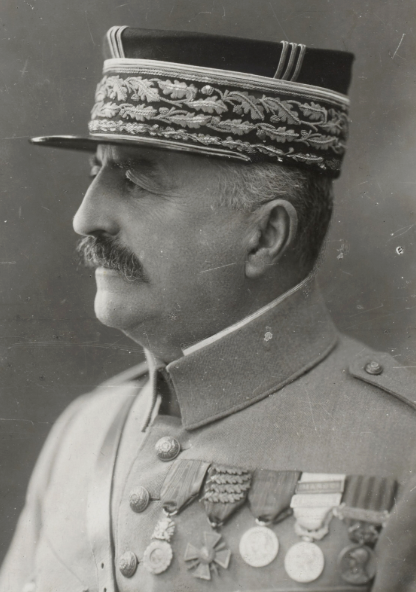

Ferdinand Foch

He was born on the 2 October 1851 in Tarbes, in the Département Hautes-Pyrénées of the Region Midi-Pyrénées, in the south-west of France. He was the son of a civil servant and joined the Army in 1870. Although he was commissioned as an artilleryman, a sphere in which he later specialised, he served during the 1870-1 Franco-Prussian war as an infantryman, but did not participate in any of the fighting.

He attended L'Ecole d'Application de la Artillerie - a specialist school on artillery - in 1873.

In 1885 Foch went to the French Staff College - L'Ecole de Guerre - where staff officers were trained, and returned in 1895 as an instructor of strategy and tactics. In 1905 he took command of this institution and held this post until 1911. His books - Principes de la Guerre (1903), Principles of War, and De la Conduite de la Guerre (1904), On the Conduct of War - definitively set out the philosophy and psychology of L'attaque [or L'offensive] de l'outrance. One of his credos was 'To charge, but to charge in numbers, as one mass: therein lies safety' was destined to ring hollow in the ears of the infantry on the Western Front.

He returned to regimental duties in 1901 and was promoted to Colonel in 1903. His next appointment, in 1905, was Chief of Staff of V Corps. After his promotion to Brigadier General, as mentioned previously, he returned to the Staff College as Commandant.

In 1911 and 1913 he became commander of VIII and XX Corps respectively.

Foch still commanded XX Corps at the outbreak of the Great War. He was then rather gaunt looking, a characteristic which, understandably, became more pronounced as the war progressed. His small, compact, stature, and nervous energy, was in complete contrast to the large, rotund figure and laid back attitude of his superior Joffre.

His success in the Battle of the Frontiers in August 1914, when his counter attack at Trouées des Charmes halted the German advance at Nancy, propelled him to the command of the Ninth Army, (28 August 1914). He played a significant role in the success at the First Battle of the Marne, and directed the counter attack that halted the German advance.

His communication to Joffre, in September 1914, when particularly under pressure, 'I am hard pressed on my right; my centre is giving way; situation excellent; I am attacking' clearly indicates his positive and vigorous, if not always casualty sensitive, attitude to war.

Despite the heavy losses he had incurred in these actions he was promoted in October 1914 to command the Northern Army Group. From January 1915, he co-ordinated the Allied armies in the Flanders Sector, including the British Expeditionary Force. The BEF found his support was not always what it should have been, leading to unnecessary losses.

During May and September 1915, he was responsible for the wasteful offensives in the Artois Offensive and earned a reputation as being rather blasé about high casualty figures. As a result of his experiences in Flanders, he became a strong advocate of the 'Breakthrough' concept which, of course, fitted in with the philosophy of L'attaque à l'outrance that he had taught at the L'Ecole de Guerre. However, as the war progressed, his fervour for the unrestrained 'offensive spirit' waned somewhat.

Promoted to Commandant of the French Army Group, in 1916 he commanded the French Sector - east of the Somme River - in the First Battle of the Somme without notable success and took most of the blame on the French side. But he served as a useful go-between when Haig and Joffre quarrelled in July 1916.

When Joffre was sacked in December 1916, Foch went too.

After a pretty miserable year as a 'consultant', General Pétain returned him to a command as Chief of the General Staff. The virtual collapse of the Italian Front in 1917, gave him his second chance when he was appointed Co-ordinator of Allied support for Italy.

His widely acknowledged success in Italy led to his appointment as co-ordinator of the Anglo-French forces on the Western Front.

With the avid support of the French Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau, and the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, who was anxious to have a counter-balance against Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the commander of the BEF, Foch was installed as the Allied Commander-in-Chief on the 14 April 1917, over the head of Pétain and other more senior officers.

Cleverly exploiting this limited power base, and with the agreement and co-operation of Haig and the rather less enthusiastic American commander, General J.J. Pershing, Foch was able to use his optimism, and now judicious offensive attitude, to marshal the efforts of all the Allies into a concerted attack on the German Army in France and Belgium.

This skilfully performed task led to an unparalleled series of Allied victories in the 100 Days Campaign and the defeat of the German Army in the field. The Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918.

Foch was made Marshal of France in July 1918 and Honorary British Field Marshal after the war.

Ferdinand Foch died at Paris, France, on the 20 March 1929 aged 77.

On his memorial plinth in London, England, are written his own words, 'I am conscious of having served England as I have served my own country.'

Joseph Jacques Césaire (Papa or Grand-père) Joffre

Almost every book and publication on the Great War will have one or more monochrome photographs of this tall, portly, white moustached, French General. Extraordinarily strong of spirit, and brimming with confidence, he will be seen looming over his contemporaries. His love of three precisely timed meals a day, with a ritual siesta, and a strictly observed bedtime, even when all around was chaos and confusion, typifies this stoic type of general from the Great War.

He was born on the 12 January 1852 at Rivesaltes in the Département Pyrénées Orientales, Region Languedoc-Rousillion, in the south-east of France. He was the eldest of eleven children of a country cooper.

He joined the French Army as a cadet in 1870.

His early service took him on foreign assignments in Indo-China and North Africa where in the latter he won distinction leading a desert foray that captured Timbuktu (now in Niger).

Having served as Director of Engineers between 1904-06, unsullied by unacceptable political or religious connections, and supported by General Joseph S. Galliéni, he was appointed Chief of the French General Staff in 1911. He held that post at the onset of the war in 1914.

In line with the attitude of the French Army of the day, Joffre had a reputation for favouring the offensive spirit, and was ruthless at weeding-out commanders who he thought were too biased towards a defensive stance.

In 1913, Joffre, with the help of General N. J. E. de C. de Castelnau, was the principal author of the Plan XVII for the anticipated war with Germany, whereby Germany would be attacked through Alsace-Lorraine if the Germans tried to invade France via Belgian territory.

Shortly after the outset of war and the German invasion through Belgium, Joffre brought this plan into effect with the Lorraine Offensive.

The offensive failed. Joffre's troops, and the British Expeditionary Force, were forced back to a position 40 miles (60km) from the River Marne, and the same distance from Paris. Here, Joffre, ever optimistic and calm, and with British help, made a stand and the legend of the 'Miracle of the Marne' was born. However, some sources claim that it was General Galliéni's dispositions (including the use of the famous 2,000 taxicabs) that really saved the day, and Paris. Also see below.

In any event, Joffre was acclaimed as 'The Saviour of France'.

In 1915, Joffre, facing what was, more or less, a stalemate on the Marne, and with the militarised zone of France firmly under his control, launched two new offensives. They took place in Artois (16 May - 30 June 1915) and Champagne (25 September - 6 November), using the standard formula of massed infantry assault and extensive barrages of shells. Both offensives failed and Joffre's troops suffered heavy losses for minimal gains.

Joffre's faith in his own military ability and fervour, and that of his soldiers, was found to be largely impotent against the German machine-guns and high explosive shells. Although the details and costs of much of the fighting were deliberately kept from the Press and public, unease began to emerge about Joffre's lack of success in expelling the German invaders and the cost in men.

This became much more vocal when his failings in the preparations for the defence of Verdun became known: he had even transferred the big howitzer guns from the forts of the garrison to other areas. These doubts about his performance were only reinforced by the ten months of carnage that subsequently took place around the captured forts.

Added to this concern was the virtual tactical failure of the joint Anglo-French offensive of the First Battle of the Somme, from July to December 1916.

Joffre's enemies among the politicians and the civil administration engineered a coup. Joffre was sacked on the 13 December 1916, and replaced by Nivelle the victor of Verdun.

In classic bureaucratic fashion, he was consoled with a Marshal of France baton and sent on a round of diplomatic missions - such as one to the United States in 1917 - and was appointed President of the Allied Supreme War Council in 1918.

After the war, Joffre continued to work at the Ministry of War.

Joffre died on the 30 January 1931, at Paris, France, aged 79.

Henri-Phillippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain

Pétain had what was surely the most exceptional career among the French commanders of the Great War. Having received the highest level of public acclaim and distinction for his military service to his country on the Western Front in the Great War, he did an extraordinary traitorous volte face in the Second World War by supporting the fascist Vichy Government. Were it not for the personal intervention of General de Gaulle, the then post-WW2 President, and a subordinate of Pétain in 1914, Pétain would have faced execution.

Pétain was born on 24 April 1856 at Cauchy-a-la-Tour in the Département Pas-de-Calais, Region Nord Pas de Calais, in Northern France to a family of farmers.

He joined the French Army in 1876 and passed through the St. Cyr Military College. He graduated as an infantryman and served in this capacity, and that of an instructor at L'Ecole de la Guerre only reaching the relatively low rank of Colonel as retirement loomed after 36 years of service. This relatively low rank may be associated with his outspoken views on the French cult of The Offensive.

The Great War intervened and the demand for experienced officers superseded any quibbles about military philosophy. He entered the war as commander of the 33rd Infantry Regiment in the 5th Army

Despite his reservations on the French Army's philosophy of The Offensive, he did very well in the field and was soon promoted. First to command a Brigade, then a Division and, in October 1914, XXXXIII Corps. His adroit handling in July 1915 of his Corps at Souchez, north of Arras, brought him the command of the Second Army that was located south of Verdun. In less than a year he had advanced from a Colonel with a regiment to a General with an Army.

When the Germans unexpectedly attacked Verdun on the 21 February 1916, Joffre sought his help.

Having not married, and despite his age, Pétain was said to be quite a Ladies' Man. He was finally found in an hotel spending the night with good company as evidenced by his having left the lady's shoes, alongside his own military boots, outside the bedroom door for cleaning. Informed of the Commander-in-Chief's request, he said he would report in the morning. A typical indication of how he faced a challenge by a show of 'sang froid'.

On 25 February 1916 Pétain travelled post-haste to Verdun to organise the defence.

He arrived to find the situation even worse than he supposed: the major defence bastion, Fort Douaumont, had fallen.

The next day he awoke with pneumonia, but using trusted aides he reorganised and re-energised the defence coining the soon to be famous war cry 'Courage - on les aura!' (Courage, we shall have them).

The basis of his success in stabilising the situation at Verdun was: the maintenance of on open access route 24 hours a day ('La Voie Sacrée'); no more irrational frontal attacks; far better and sustained use of the artillery; and a fair system of rotation of the troops. This rotation ensured that over 78% of the Regiments of the French Army took their turn in the Verdun Sector.

Once the situation was seen to be stabilised, Joffre became impatient for the more standard French Army offensive approach and arranged for Pétain to be moved to command the Army Group Centre.

The young high-flier General Robert Nivelle took over Pétain's command in Verdun.

On the strength of his counter attacks that led to the recovery of much of the territory lost at Verdun, Neville also by-passed Pétain to become C-in-C of the French Army in December 1916 after Joffre's abrupt departure.

However, when Nivelle's offensive in the Chemin des Dames Sector failed in ignominy in late April 1917, Pétain was asked to return to Verdun in Nivelle's job as C-in-C, to face what was perhaps an even greater challenge than the defence of Verdun.

Due largely to Nivelle's mis-use of his troops, a long festering disaffection in the French Army boiled over and mutinies occurred: the troops refused to take part in any new offensive actions. Despite the most draconian measures by the commanding generals, the mutiny could not be contained. Pétain was given virtually 'carte blanche' to find a solution. Fortunately, the Germans did not realise the gravity of the situation - or chose to ignore it for their own reasons - so Pétain had a small breathing space. The French troops also continued to man the Front Line.

It took him several months, but by a judicious use of discipline, concessions and morale boosting improvements in the daily régime and conditions of the ordinary soldier, he brought the mutinies to an end and set the French Army on the path to operational readiness.

In October 1916, the first post-mutiny offensive action took part at Malmaison under Pétain's direct guidance, and success was achieved. The French Army was indubitably damaged, as events years later were to show, but was once again operational, to the relief of the Allies.

Despite his success, Pétain developed something of a reputation of being cautious and, on occasion, even defeatist. However, he retained his post as C-in-C, if subordinate to Foch, and played an exemplary and enthusiastic role in the last phase of the war.

At the end of the war he was rewarded by promotion to Marshal and, to general surprise, married in 1920 aged 66.

He died in disgrace as a traitor, in exile, on the 23 July 1951, on the Ile d'Yeu, south-west of the port of Nantes in the Atlantic Ocean, aged 95; his wish to be buried with his men on the battlefield of Verdun was ignored.

However, the fates have been kinder in giving him a more positive sort of immortality. The words he sent his troops in an order of the day, during the time of crisis at Verdun, stating, 'Ils ne passeront pas' (They shall not pass), became the principle battle cry for the French Army. Today, these words can be seen carved upon the war memorials to the dead of the Great War, across the length and breadth of France.

Noel Joseph Edouard de Curières (Le capucin botté - The booted friar) Vicompte de Castelnau

Castelnau was a much more important French General than British war historians tend to indicate. At crucial events such as the Battle of the Frontiers in 1914 and Verdun in 1916, Castelnau played a significant role; he was a fervent devotee of the Offensive Stance.

Born on the 24 December 1851 at Aveyron, in the Département Aveyron, in the Region Midi-Pyrénées of the southern Massif Central, north-east of Toulouse, France, of a prominent religious and military family, he was destined to serve in the French Army. He gained his spurs in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

An unfortunate involvement in the infamous anti-Semitic Dreyfus affair cost him his post in the General Staff in 1900.

By 1911, Castelnau had been rehabilitated to the extent of being appointed as Joffre's deputy, in which capacity he had an important input into the formulation of Joffre's Plan XVII for the invasion of Germany via Alsace-Lorraine, if the anticipated invasion of France via Belgium indeed took place.

At the outbreak of the war in 1914, he was well placed to play an important role and was appointed to command Second Army. As such he attempted to implement Plan XVII. His advance was halted at Morhange-Sarrebourg with heavy losses.

His staid, religious outlook on life was reflected in the nickname given to him by his troops - 'The booted friar'.

He had much more success in the Battle of Grand Couronné of Nancy in north-eastern France (31 August - 11 September 1914) and became to be known as 'The Saviour of Nancy'.

After this success, in June 1915 he was appointed to the command of Army Group Centre; still committed to the cult of The Offensive.

In September 1915, he directed the Second Battle of Champagne (25 September - 6 November 1915) but without achieving a breakthrough.

Once again made deputy to Joffre in February 1916, he oversaw the planning for the defence of Verdun and was responsible for the decision to resist at all costs. He also nominated Pétain to take command.

With the fall of Joffre in December 1916, his star had begun to decline and he retired. But in 1918 he was recalled to command the Eastern Army Group in the final campaign in Lorraine.

He lost three sons in the war and never received his Marshal's baton.

Castelnau died on the 19 March 1944 aged 93.

Louis Felix Marie Francois ('Desperate Frankie') Franchet d'Esperey

He was born on the 25 May 1856, at Mostaganen, Algeria, of a political and religious family. He spent most of his military career in fighting colonial wars and in the Balkans; he treated the latter as a special area of study. Knowledge gained from these studies was to approve of vital importance in enabling his successes on the Balkan Front in 1918.

To be thrust into the maelstrom of the Western front in command of I Corps, at the age 58, must have been somewhat traumatic. But his independent and self-possessed nature enabled him to do well enough to rise to the command of the 5th Army, replacing Lanrezac on the 3 September 1914 on the eve of the First Battle of the Marne. Success in the battle (5 -10 September 1914) and a generally consistent, and aggressive, performance in the field gave him the command of the Eastern Army Group in 1915. Command of Northern Group followed in 1917.

His British Allies held him in high regard, hence the humorous English nickname.

He was considered for the post of Commander-in-Chief when Joffre was sacked in December 1916, but his religious and political affiliations weighed against him, and the job went to Nivelle, who had less seniority.

His Northern Group failed to meet expectations in the Third Battle of the Aisne in the Chemin des Dames Sector, in May 1918. And he was sent back to the Balkans he had got to know so well in the pre-war days, as Allied Command-in-Chief, Salonika. (June - November 1914)

Away from the strictures and hierarchy of the Western Front, he seemed to find inspiration and drive once again. In a battle that lasted from the 14 - 26 September 1918, he successfully defeated a joint Bulgarian-German Army at Vardar taking Bulgaria out of the war. Churchill described this battle as the beginning of 'The Final Phase of the War'.

Francet d'Esperey then made a bold thrust to the River Danube that resulted in the collapse of the Germany division that had been rushed from Russia, and led to the surrender of Hungary. He also proposed audacious advances into Austria and Germany from the Balkan Front, but the war ended before these proposals could come to fruition.

He was promoted to Marshal of France in 1922 and died at Albi, north-east of Toulouse, France on 8 July 1942 aged 86.

Joseph Simon Galliéni

Born on the 24 April 1849, at St. Béat in the Département Haute Garonne, the Region Midi-Pyrénées in the south-east of France, he was the eldest of the Generals and Marshals considered here. He was trained at the St. Cyr Military College and graduated just in time to serve in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71.) He fought at Sedan where he was wounded and captured, being released in 1871.

During his military career, he served in many colonial posts - such as West and East Africa, Martinique and Indo-China - becoming known as a specialist in the prosecution of small colonial wars and a proponent of what we would now call 'hearts and minds' campaigns.

In 1886, he was appointed Governor of Upper Senegal and, in 1897, was relocated to Madagascar as Governor General, where he served with distinction and public affection, until 1905.

Due to ill health, and what he called old age, in 1911 he ceded the offer of the post of Commander-in-Chief of the French Army to Joffre.

In fact, in early 1914, Galliéni thought his military career was over, and he retired a few months before the Great War began.

However, he was also well known as a military theorist and this, perhaps, was part of the reason why he was recalled to duty in August 1914 as Commander-in-Chief Joffre's deputy. His principal task was to undertake the difficult job of organising the defence of Paris. His immediate response was to warn the French Government that the Germans would be in Paris by early September, and set to with great energy to mobilise all the available resources.

Galliéni's most significant action at this time was to realise, in September 1914, that the van of the German Army was turning, quite unexpectedly, to the East of Paris. He expeditiously despatched the French Sixth Army - later backed up by reinforcements of newly arrived Zouaves that were transported in the famous 2,000 Paris taxi-cabs - to intercept them on their flank. This played a significant, if not the major, role in the subsequent halt in of the German advance on the Marne.

In October 1916, the politicians appointed him as War Minister with a brief to reimpose Government control over Joffre's independent High Command structure.

Joffre's resilience, and the unconditional support of the general public, made Galliéni's task virtually impossible. After serious disagreements with Joffre, particularly about the defence of Verdun, Galliéni resigned in March 1916.

The stress of Galliéni's final stint of military service had affected his health. He died at Versailles, Paris, France, on 27 May of the same year, aged 67.

Galliéni's contribution to the defence of Paris and 'The Miracle of the Marne' was initially overshadowed by Joffre's, and it was only after the war that war historians began to give him some due recognition.

Somewhat belatedly, in 1921 Galliéni was posthumously promoted to Marshal of France.

Robert Georges Nivelle

If ever there was a general who was promoted to a level beyond his competence, it was Robert George Nivelle.

He was born on the 15 October 1856, at Tulle, Département Correzè, Region Limouzin, to an English mother who had strong social connections. Nivelle's fluency in English and the contacts of his mother, propelled him headlong into over-rapid promotion and an exaggerated belief in his own abilities. It brought him, and a considerable part of the French Army, to disaster.

He was commissioned in the artillery in 1878. He spent his early career on colonial duties in North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and also in China. He served in all of them with distinction.

He began the Great War as a Colonel commanding an artillery regiment. He used

his guns with great skill to stall the German Army in Lorraine during the Battle of the Frontiers in August 1914, and showed similar efficacy in the First Battle of the Marne (5 - 10 September 1914) and the First Battle of the Aisne (15 - 18 September 1914).

Promoted to General in October 1914, Nivelle quickly rose in 1915 to the command of III Corps. Command of Second Army followed in April 1916. This, in turn, led to his much acclaimed success in The Battle of Verdun, under General Henri-Philippe Pétain. The recapture of the psychologically important Fort Douaumont in the Verdun Sector, on 24 October 1916, was followed by the successful counter-offensive along the Meuse in October and December 1916.

Much of the preparatory planning for these actions had been done by Pétain's Staff. But Neville's innovative use of the artillery, laying down a 'lightning barrage' followed by 'creeping barrage' that would closely precede the advancing infantry right up to the enemy lines, was generally acknowledged. That he claimed the 'creeping barrage' idea his own is less supportable: General Sir Henry Rawlinson of the British Fourth Army had previously experimented with, and used it to some extent, in the First Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Even less portentous was Nivelle's slogan ' We have the formula to end the war in 48 hours? Victory is certain'.

Such was the public acclaim, and the behind the scene support - including that of the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George which was influenced by his feuding with Haig - that Nivelle was given Joffre's job as Commander-in-Chief on 12 December 1916.

Nivelle's answer was the Nivelle Offensive that took place in the Chemin des Dames Sector (Arras/ Soissons/Rheims). Haig was made his subordinate for the duration of the British diversionary attack in the Arras/Vimy Ridge Sector - The First Battle of Arras (9 -15 April 1917).

Nivelle's concept for the offensive - the Second Battle of the Aisne (16 - 20 April 1917) - was a development of the one he used at Verdun. A 'lightning barrage' followed by a mass infantry attack on a broad front, with the additional support of tanks. And, of course, the famed 'creeping barrage' that immediately followed the 'lightning barrage'. There was no give-away pre-attack, sustained barrage.

Unfortunately, Nivelle and his Staff in their hubris had neglected their Intelligence sources. In the Spring of 1917, Ludendorff had begun the withdrawal of his forces behind the newly created Hindenburg Line, 60 miles east of the Somme battlefield. Nivelle had also openly boasted to all and sundry about his tactics, so the Germans were warned well in advance of the attack. They had even captured a map and the plan of attack from an incompetent French field officer.

Due to these intelligence failures, and delays in the planning and protocol clearance process, the outcome, if not pre-ordained, was inevitable.

The preliminary barrage was activated on the 5 April 1917 but, due to bad weather, the main infantry and tank attack was stalled until the 16 April 1917.

The French infantry charged into what became a virtually empty, denuded, wasteland with judiciously located tank traps, well-sited machine-gun bunkers and artillery gun sites that produced a withering fire. By the 29 April 1917, 134,000 French had become casualties (over 100,000 the first day).

A limited advance was made in some areas, but the attack had generally failed. Neville in desperation continued the operation, reverting to the old ideology of L'attaque à l'outrance' and the new edict of 'attrition' hoping for the promised 'Breakthrough'.

The outcome was the breaking of the French soldier's spirit: elan had failed, crushed by the realities of the battlefield. The troops of the 18th Infantry Battalion of the 21st Division mutinied. Other outbreaks followed until 54 divisions - 50% of the French Army - were involved to some extent.

Nivelle former supporters turned on him. 'Carrying the can' time had arrived, but Nivelle refused to resign, blaming the failure of the Offensive on his second-in-command, General Charles Mangin.

Nivelle was literally pushed out of office, and on the 15 May 1917, replaced by Pétain. He was subjected to a humiliating Court Martial for negligence and incompetence. Whilst found Not Guilty, he was hustled away to exile in a backwater post in North Africa. In 1921 he retired.

He did not write any memoirs, nor make any public statements.

He died at Paris, France, unlamented by the French public on the 23 March 1924, aged 67.

Afterthoughts

These seven French Generals/Marshals are probably the most important French commanders on the Western Front in the Great War; obviously, some played a much more important role than others.

But there is one more commander who, perhaps, should be mentioned for four reasons:

1) His role in the preparations for the expected European War (i.e. against Germany) and the way it was destined to be fought by the French;

2) The critical role he played in the initial phase of the war;

3) The psychological effects he suffered when his theory of war did not match the realities of the battlefield;

4) The ephemeral nature of his command when, in the crucible of the battlefield, his martial achievements, and the turn of events largely beyond his control, did not combine to give the success that was expected of him.

Charles Louis Marie Lanrezac

Born on 31 July 1852 at Pointe-à-Pitre on the French island of Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, he became a protégé of Joffre. He gained a reputation as one of the most ardent advocates of the 'L'attaque à l'outrance' and the strategies and tactics that evolved from it. In this he was strongly supported, and encouraged, by Joffre, a fellow adherent. However, like many strategists, he came to grief when he tried to implement the tactics of the offensive stance in the crucible that was the Western Front in 1914.

In August 1914, Lanrezac was a member of the Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre (Surpreme War Council) and the commander of 5th Army. He led the deployment on the Franco-German border according to the edicts of Plan XVII whereby he was poised to sweep eastwards into Germany through Lorraine and Alsace.

However, he realised that there was an obvious flaw in the disposition of his troops. He firmly believed, contrary to Joffre, that an attack was possible from the North. He pestered Joffre to allow him to redeploy his troops along the Sambre River to be ready to counter-attack against any German offensive from the North through Belgium. Joffre finally agreed, although in the process Lanrezac lost some of his best troops in exchange for a single Corps from Second Army. His demands for reinforcements were considered to be over-exaggerated and this, and the failure of the BEF to take up its designated position adjacent to his Army, meant he faced, alone, a vastly superior force of 38 German divisions.

Joffre ordered Lanrezac to attack on the 21 August 1914, with his 18 Divisions across The Sambre at Charleroi, an industrial town on the Sambre River. The objective was the German Second and Third Armies that had moved towards the south-west through Belgium. Lanrezac postponed the attack and asked Joffre if he could wait for the British to get into position.

Meanwhile, the German Second and Third Army attacked across the river on the morning of the 21 October 1914, and successfully repelled French counter-attacks by poorly supported troops.

The German commander - von Bulow - launched another attack on Charleroi on the 22 August 1914 with chaotic results for the French Army. The troops in some sectors held, whilst in others they retreated. The BEF, finally in position at Mons, was left exposed by the retreating French cavalry. Communications were poor and dispositions of the other units of the French engaged in the action, became unclear to Lanrezac. Fearing his line of retreat would be cut, and with news that the Fourth French Army was in retreat in the East, Lanzerac ordered a withdrawal to save Fifth Army, which it indubitably did. In the process he supported the BEF east of Paris winning a tactical victory at Guise on 29 August 1914.

Condemned by Joffre and his British counterpart - General Sir John French - as having a failure of the 'offensive spirit', Lanrezac was considered to be unfit to lead the counter-attack on the Marne and sacked. General Louis Franchet d'Esperey took over just in time for the French successful counter attack on the Marne.

Lanrezac sat out the war for two years on the sidelines acknowledged as having timely spotted a vital flaw in Plan XVII, but in terms of military tactics - L'attaque à l'outrance' - a failure.

In 1917 Lanrezac was offered another command but declined. He died on he 18 January 1925, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Paris, France, aged 72.

Postscriptum

It is remarkable that all of these eight notable Generals/Marshals of the Great War were born in a span of just seven years, 1849 - 1856: seven in the five year span 1851 - 1856. It is perhaps less remarkable that all but two lived to an advanced age, averaging 79 years: bearing out the observation that grand commanding generals rarely succumb to the vagaries of war in the field. Generals of lower rank are less fortunate - 58 British generals of lower rank died in the Great War.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

Identify key words or phrases within back issues of our magazines, including Stand To!, Bulletin, Gun Fire, Fire Step and lots of others.

The WFA's YouTube channel features hundreds of videos of lectures given by experts on particular aspects of WW1.

Read post-WW1 era magazines, such as 'Twenty Years After', 'WW1 A Pictured History' and 'I Was There!' plus others.

Other Articles