Woodbines on the Western Front

Since the Sixteenth Century soldiers have always found solace from the tedium of war by smoking tobacco. Usually, it was smoked in the white 'Church Warden' clay pipe that is the feature of many archaeological sites associated with the battles of the recent and the not so recent past. The pipes were cheap, if not too durable, readily available almost anywhere, and when inverted could be smoked in really foul weather. The pipe-shrouded, burning tobacco was also shielded at night, thus evading the eye of the sniper.

The cigarette

For the 20th Century soldier of the Great War, a new even more readily portable source of smoking tobacco was the paper tube filled with tobacco - the cigarette [O.E.D. circa 1842]. The British soldier never did take to chewing tobacco - as their American counterparts did - although powdered tobacco in the form of snuff was widely used by both the lower ranks and their officers up to the highest ranks.

Morale factors

The British military and political authorities, aware of the and morale boosting affect of the cigarette - most had sons and other relatives serving in the trenches - facilitated the supply of cigarettes to the front where they would be distributed and sold by soldiers canteens. The free flow of mail packages to the Western Front was also facilitated, so that relatives and friends could send items of preserved food and packages of cigarettes to the men in the trenches.

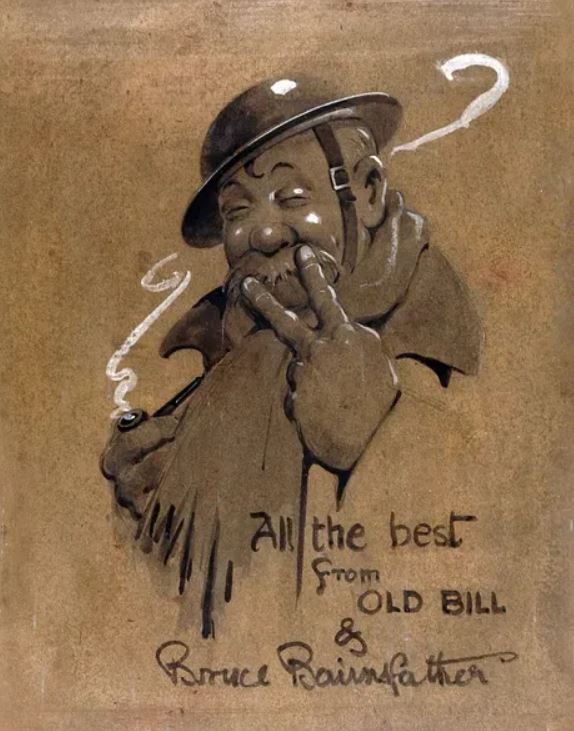

Whilst many of the men in the trenches were not cigarette smokers - or smokers at all - before joining the army, the majority quickly took up the habit, and found that the ubiquitous cigarette became a staple of the life in the trenches. Although, perhaps the most famous character of the war, the cartoon figure of 'Old Bill' created and drawn by Bruce Bairnsfather, an officer of the Warwickshire Regiment who served in the trenches, stuck faithfully to his pipe - always depicted as inverted.

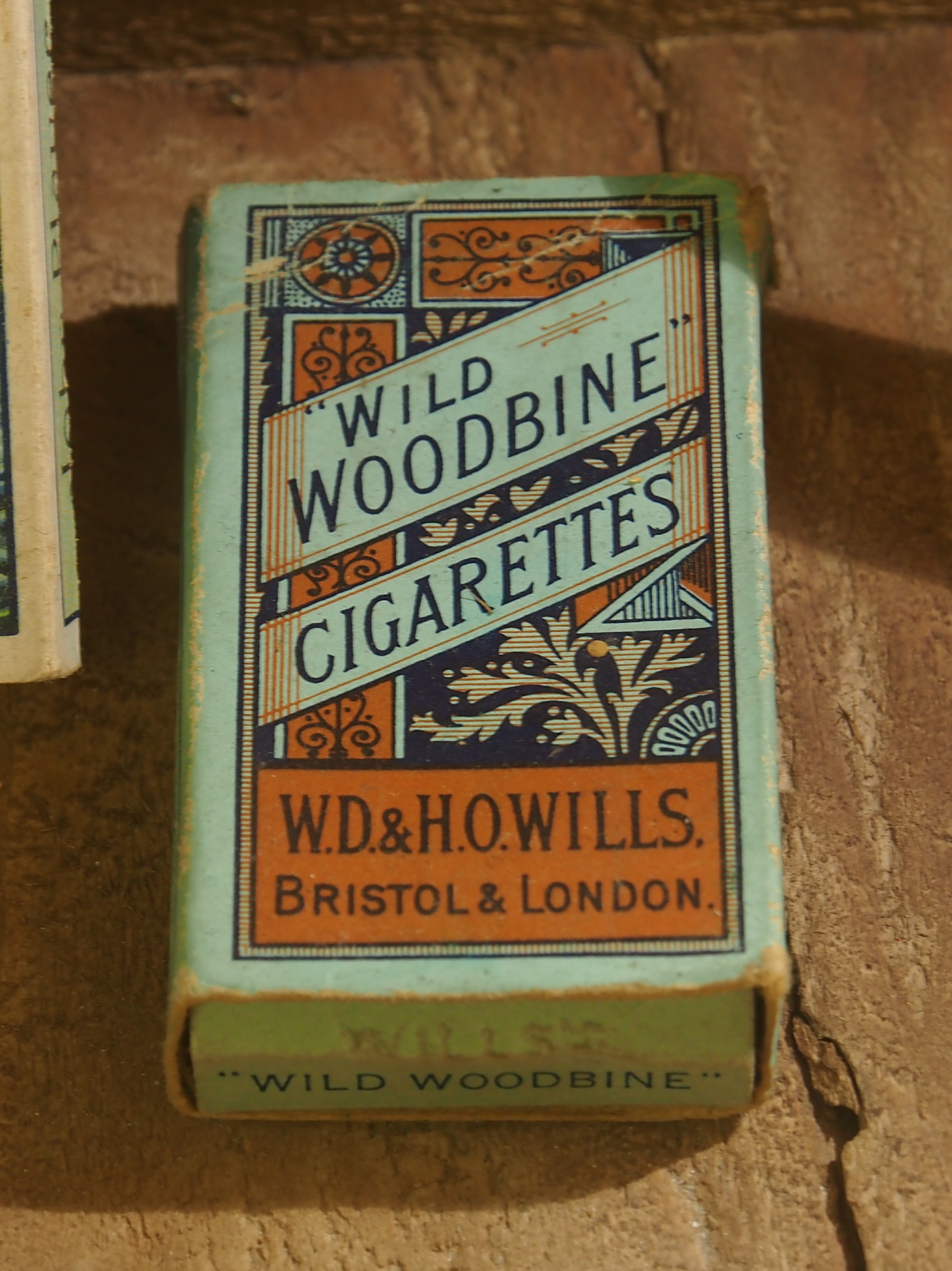

As the War dragged on, the favourite cigarette of the British soldier became the 'Woodbine' produced by the British tobacco giant W.H. Wills in their Bristol, England, factory.

But large numbers of soldiers preferred to roll their own cigarettes from loose tobacco held in leather pouches, and the famed Rizla cigarette papers. Often the more cash- stricken soldiers (the British Expeditionary Force infantryman's pay was one shilling a day [5p] minus barrack charges) 'recycled' their part spent-cigarettes into these pouches.

Health factors and customs

The deleterious effect of this sudden boom in tobacco smoking in all its forms, in these predominantly young men, is not recorded. Many people at the time, including doctors, some of whom were inveterate smokers themselves, considered smoking as beneficial to both mental and physical health. One brand of cigarette called 'Craven A' even claimed - uncontested - to be 'The cigarette that soothes the throat'. In infantry battalions that had suffered a 50% casualty rate on one, or even more, occasions, such musings about the harm tobacco could do, is likely to have fallen on deaf, or deliberately unhearing ears. Tobacco was a comfort in a very hostile environment. If anything the authorities approved of it, and on all except formal occasions and parades it could be indulged in without sanction. Moreover, cigarettes were readily portable in the pocket - usually stored inside a tin to prevent accidental damage and to keep them dry - so as to be immediately available on demand. Also, not to be depreciated, was the strong feeling of friendship that often came from offering and/or sharing a cigarette with one's comrades-in-arms.

One of the most enduring anecdotes of the Great War came from the practice of sharing cigarettes in the front-line. It was said that it was unlucky if three people shared the same light. When the first soldier lit his cigarette, the sniper would see the flame. When the second soldier lit his cigarette, the sniper would take aim. And when the third smoker lit his cigarette, the sniper would fire. No doubt superstition raised its head here, but assuredly events such as this did occur in the trenches. Also, after the Great War it was usual to see men who were smoking hold their cigarette cupped in their hand, rather than the usual stance of slotting it between the index and middle finger. The cupping action would be the one they learned to use in the trenches to shield the burning tip of the cigarette from view.

Perhaps, the first occasion when the deleterious effects of cigarettes did become apparent was in the victims of gas poisoning, where damage to the lungs had occurred. The natural by-products of tobacco were very pernicious to the damaged membranes of the lungs and led to chronic coughing and inflammation (bronchitis). Sadly many of the gassed men were so addicted to the nicotine in tobacco smoke by then, that they refused to give up; despite all the discomfort they suffered as they continued to smoke.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

The WFA regularly makes available webinars which can be viewed 'live' from home. These feature expert speakers talking about a particular aspect of the Great War.

Featured on The WFA's YouTube channel are modern day re-interpretations of the inter-war magazine 'I Was There!' which recount the memories of soldiers who 'were there'.

Explore over 8 million digitized pension records, Medal Index Cards and Ministry of Pension Documents, preserved by the WFA.

Other Articles