Who started The First World War?

After all the research, thousands of books, learned papers, and articles, all the different explanations of who is to "blame" for the Great War are still in the running.

Germany by itself, Germany and Austria-Hungary, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Russia egged on by France, nobody is to blame, Europe slid into war, everyone is to blame, Britain sat on the fence for too long, the mobilisation timetables....

The "Germany by itself" version published in 1961 by Hamburg historian Fritz Fischer, that Germany deliberately and carefully implemented a well laid plan for world domination, "Griff nach der Weltmacht" (grab for world power) now has little support. There is next to no evidence for such a plan in the period before the war.

Much more popular is the view that the German leadership was a shambles and they miscalculated and ran risks on a grand scale. The Kaiser and the civilians and some of the military didn't want a European/World war, but they were prepared to risk it.

New works

At least two new books are out and more expected over the coming months as the centenary approaches. The first published is "The Sleepwalkers" by Christopher Clark, an Australian, and Cambridge University professor. After an excellent account of the decade before the war including the events that created such bad relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, he makes a good case for "everyone is to blame".

The other published new book, "July 1914", heaps all the blame on the Russians set on their ambition to take control of the Turkish Straits, eagerly pushed along by the French who, in the ensuing war, see a chance to liberate Alsace-Lorraine. Unfortunately, this book has numerous errors, and the provenance of the author, Sean McMeekin, an American, and assistant professor at a Turkish university raises some questions.

But whatever the merits of the "Turkish Straits" argument, Russian actions warrant close examination. The Russians ordered their "Period Preparatory to War" in all European military districts including those facing Germany, as well as Austria-Hungary, before the Serbs had even replied to the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum.

Some historians view this as effectively the first decided steps of Russian general mobilisation. The Chief of the Mobilisation Section of the Russian General Staff, General Dobrorolsky thought so. He later said 'The war was already a settled matter, and the whole flood of telegrams between the Governments of Russia and Germany represented merely the stage setting of a historical drama'.

How to allocate blame

Often missing from accounts of the outbreak of the war or there only by implication are the criteria for allocating blame. How do you find fault? What carries the most weight, principles or practicalities?

What were the rights or wrongs of Austria-Hungary's decision to invade and break up Serbia in response to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Empire, and his wife? Is it right that a Great Power should invade a small nation to ensure a crime, recognised internationally as outrageous, is not repeated or to prevent even worse things happening? There was no United Nations in 1914.

Or should one examine how the crisis played out, the events and decisions, who or what made it worse: the failure of Serbia (encouraged by Russia) to give a satisfactory reply to the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum; the French promise of their complete support to the Russians; German duplicity (while pretending to support mediation, the Germans pushed the Austro-Hungarians into military action against Serbia); premature Russian mobilisation, the divisions in the British cabinet.

If the Austro-Hungarians had struck quickly seizing Belgrade, the capital of Serbia just across the border, without an ultimatum or a declaration of war, presenting Europe with a fait accompli as the Germans wanted, the crisis might have eventually been solved by negotiation. But they moved very slowly. Many regular troops were on harvest leave and the objections of the Hungarian prime minister had to be overcome.

Intelligence, information, incompetence

At the beginning of the crisis the German Kaiser believed Russia would not fight for Serbia and that France would not give military support to its Russian ally, the reason in both cases being military weakness. The Russians hadn't completed their modernisation and expansion programme and an opposition French politician had "exposed" the inadequacy of French artillery and fortifications.

This must rank as one of the greatest failures of political and military intelligence in modern times. Or the Kaiser and the men around him completely ignored the experts. As things turned out, the Russians and French didn't hesitate to take military measures and were fully prepared to fight. The French even considered the circumstances ideal for an Entente victory.

The Germans also believed Britain would remain neutral. There was evidence for this. George V met Prince Henry, the Kaiser's brother, and gave him the impression that Britain wanted to stay out of any European conflict. Even Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, spoke as if Britain would remain aloof.

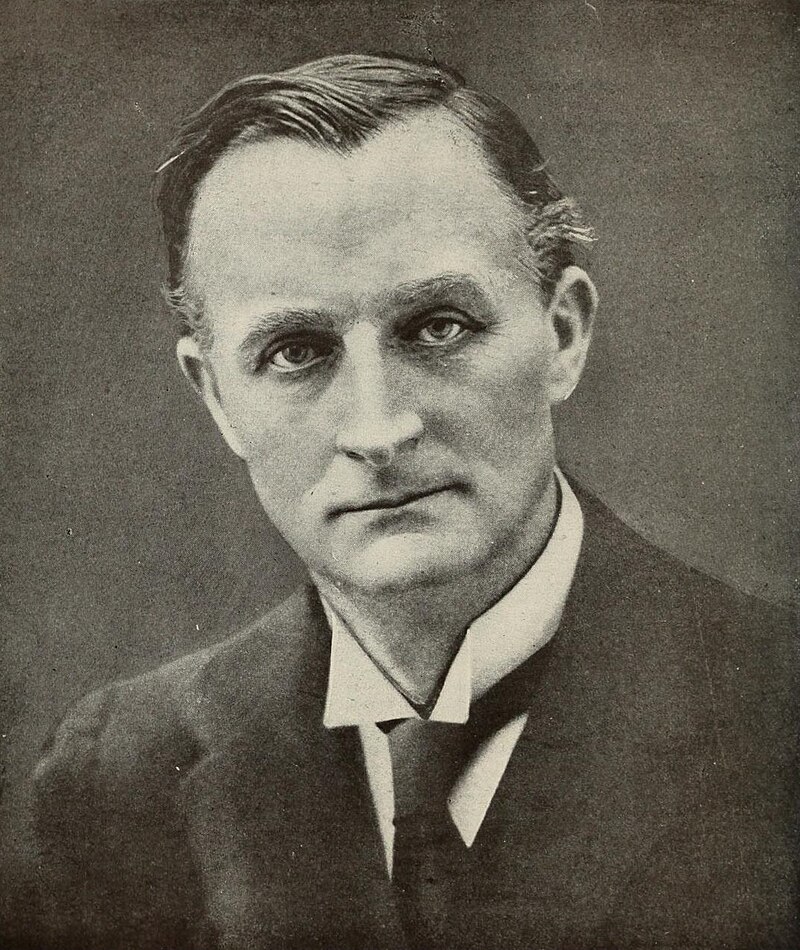

It was Prince Lichnowsky, the German ambassador in London, who foresaw what would happen. He continually warned Berlin that Britain would fight in support of the French if Germany attacked France. If only they had listened to him.

Key civilians did not understand the complexity and consequences of the military measures they supported or proposed. The military measures initiated by Sazonov, the Russian Foreign Minister, dramatically changed the nature of the crisis in ways he did not foresee.

Jagow, his German opposite number, told the British and French ambassadors in Berlin that Germany would not mobilise if Russia mobilised only on the Austro-Hungarian border and thus did not directly threaten Germany. He was ignorant of the fact that Austria-Hungary would move to general mobilisation to counter the Russian threat, and under the German and Austro-Hungarian military alliance, in that case Germany also had to mobilise. And German mobilisation led immediately to war.

Organisation and human factors

In Germany and Russia the military and civilian leadership structures were independent of one another, being authoritatively coordinated only at the very top, and the two men at the very top, Kaiser Wilhelm and Tsar Nicholas, couldn't have been more unsuited for that vital role.

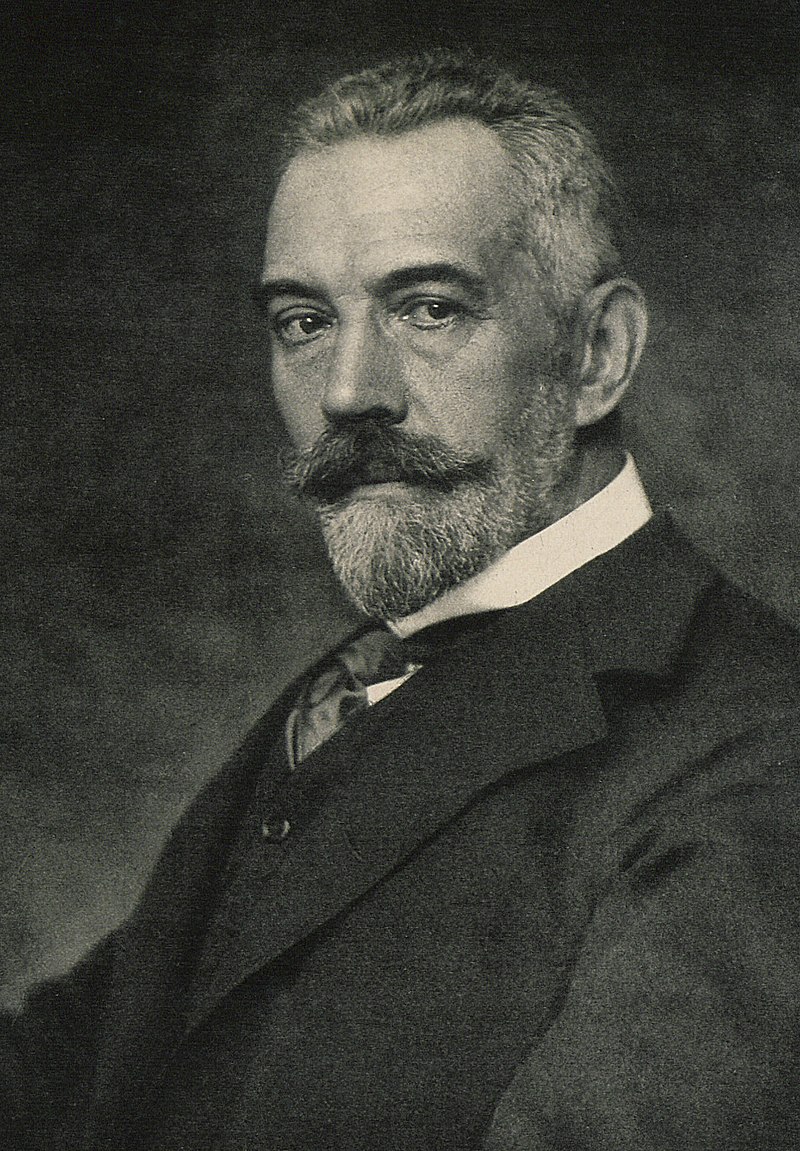

When Bethmann, the German Chancellor, realised war would break out, the Russians were going to fight and the Royal Navy was on its way to its war stations at Scapa Flow, he sent frantic wires to Vienna telling the Austro-Hungarians to modify their objectives.

Almost in parallel Helmuth von Moltke, the Chief of the German General Staff, was wiring his Austrian counterpart urging general mobilisation against Russia. Forget the Serbs! These conflicting messages elicited the remark from Berchtold, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, "Who rules in Berlin?"

What is most striking is the small number of men involved in each country.

The excuse is sometimes made that the leaders in 1914 foresaw a short war like the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, but that was not the case. Distinguished military men warned future wars would be long and destructive on an enormous scale. As the last moments of peace ticked away Sir Edward Grey made the famous remark "the lamps are going out we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime".

At the height of the crisis on 29 July 1914, the day after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the extent of Russia's military preparations were known to the Germans, von Moltke, in a report to the Kaiser and the German Chancellor, spoke of a "world war". Europe's civilized nations were about to embark on a "mutual tearing to pieces", .... "fate," was about to unleash a war "that will destroy civilization in almost all of Europe for decades to come".

A ghastly fatalism was at work and it gripped these small groups of men, unaffected by, or ignorant of, the views of others, especially in Germany, and it led them to take terrible risks and to gamble with the fate of Europe.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles