I spent this morning on Chunuk Bair

I did it the easy way, getting there by car from Eceabat at 4.30am – a drive through the night across a silent plain, past the Turkish Simulation Centre and then up a ridge line along the Anzac front line, no traffic, the only noise the rushing of the wind that came in gusts, each like an approaching semi-trailer. On Chunuk Bair all was in darkness, I parked by the sole vehicle, a white van, unaware that the two security guards were dozing inside. All around me the tents and marquees, scaffolding and equipment for this afternoon’s New Zealand’s ceremony.

Above a clear starlit sky with a bright crescent moon.

I walk to the New Zealand Memorial to the Missing from the Battle of Chunuk Bair, and look out over the low stone parapet towards the Straits of the Dardanelles, the shore line clearly etched with lights and partly out of sight, the lights from Canakkale reflected in the night sky. I sat and thought about that morning one hundred years ago today. No one of the New Zealanders who fought here ever imagined that they would end up on this hill in Turkey. Seeing in the dawn for the first time the Narrows which was the strategic goal of the Allied landings in April 1915. Now four months into the campaign this was the last major obstacle, and the goal was in sight.

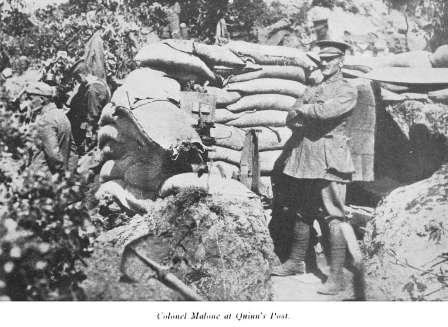

I walk back past all the names of the 853 missing with no known graves indecipherable in the dark to the top of the firebreak that comes up over the saddle from Rhododendron Ridge. I try to picture the Wellington Battalion at the Apex and its moving forward at 4.30 in the morning with artillery and naval gunfire landing where I stand. Lieutenant Colonel William Malone commanding the Wellington Infantry, forms them up in solid column of eight files, two companies up, each of four platoons, eight files of perhaps 35-45 men in each file, with the same for the rear two companies behind, scrambling their way up this stony slope. They pause in the saddle for the artillery fire to lift then sweep forward onto this crest, overrunning the sole machine gun. They peel left and right to occupy what was perhaps a half metre deep single trench sited to cover such an approach up the hill, except that on this morning one hundred years ago, it was deserted, its defenders driven off by the artillery fire.

I listen for the sounds of an eight hundred strong battalion digging in.

Already the sky is getting light. The forward two companies detached outposts of eight to 10 men forward to give early warning, while the existing Ottoman trench became the Wellington Battalion front line. It is hard ground and we know that they chipped away at it with their entrenching tools with each soldier filling two sandbags and stacking them in front to give further protection.

Behind them 30-40 metres down the slope the 400 men of the two support companies had real digging to do, only Malone’s Battalion Headquarters was spared as they occupied the captured machine gun trench which can be still identified in the dawn.

Forward towards the Straits, New Zealanders manned outposts. Among them were men I later got to know: Charlie Clark, was playing cards that morning, Harvey Johns was sniping at the Turkish mule convoys that he could see below him in the valley.

The Wellingtons were not alone.

Two British battalions followed them up onto the crest. The 7th Gloucesters were to extend our hold on the crest to the left onto Hill Q and following them, the 8th Welsh Pioneers were to extend our grip to the south. It did not happen. By now in the light of the dawn both battalions came under Turkish fire before reaching the hill and in attempting to extend the line on each flank, each was quickly driven back by Turkish fire as it became light. The Turkish response was immediate and ferocious. Both British battalions suffered such casualties that it became Wellington’s battle. Our outposts withdrew at the run and took their place in the crest line trench. By 8 am the Wellington front line was overrun. The trench itself, full of New Zealand dead and wounded, who were then bayoneted as the Turks fought their way along it. Some, all of them wounded, were taken prisoner.

It is light by 5.30 with the sun coming up over at the hills on 6am. I walk down firebreak to where the cleared area meets the trees. This is Malone’s support line, which becomes the front line for the next two days. The trenches are still evident - ragged uneven slits in the earth that were hastily dug using the dead as sandbags to give protection. I try to imagine the hundreds of men who fought here, with the 57-year old Malone leading them in counterattack after counterattack to deny the Turkish attackers the chance to consolidate on the crest above. It is an untenable position, Turkish piecemeal attacks and New Zealand tenacity defied that reality.

Malone is the heart and soul of the defence as his Battalion dissolves and dies around him. Two squadrons of Auckland Mounteds reinforce them that afternoon and the position continues to hold. All day two New Zealand 4.5-inch howitzers provide fire support lobbing shells over the crest to where the Turks mass for each attack. At about 5pm, a change in atmospherics and temperature means that a bracket of shells land this side instead of over the crest, killing Malone. The remaining New Zealanders fight on. That night they are relieved by the Wellington Mounted Rifles and the Otago Infantry and the epic is repeated all day on 9 August. By nightfall, New Zealand has no more men to give. They are replaced by two raw British battalions who are engulfed in Kemal’s counterattack on the morning 10 August.

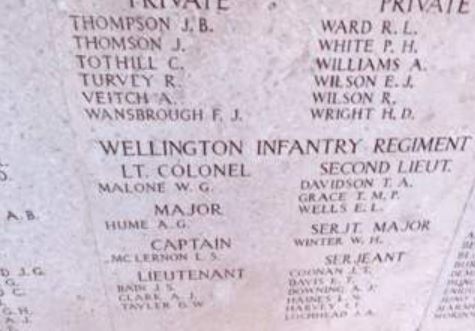

I walk the New Zealand line visualising the life and death struggles in each trench at every metre, but all I hear is the wind. It is hard to imagine almost one thousand New Zealand dead, 853 of whom have no known graves. Hundreds of wounded cluttered these seaward slopes, some begging their mates for a bullet to put them out of their misery. The wind drowns their voices and I must use my imagination. I do one more walk along the Memorial Wall and doff my hat to each panel seeking out familiar names: Malone, McCandlish, Winter, Warden, Dunn, Harrison, Statham, Mackesy, Elmslie, Chambers, Kelsall, Grace, Manuel and all.

I know their faces and have read their words. War does not deserve such sacrifice, but despite its tragedy and waste, the courage of brave men who stood by one another shines through.

Becoming a member of The Western Front Association (WFA) offers a wealth of resources and opportunities for those passionate about the history of the First World War. Here's just three of the benefits we offer:

With around 50 branches, there may be one near you. The branch meetings are open to all.

Utilise this tool to overlay historical trench maps with modern maps, enhancing battlefield research and exploration.

Receive four issues annually of this prestigious journal, featuring deeply researched articles, book reviews and historical analysis.

Other Articles